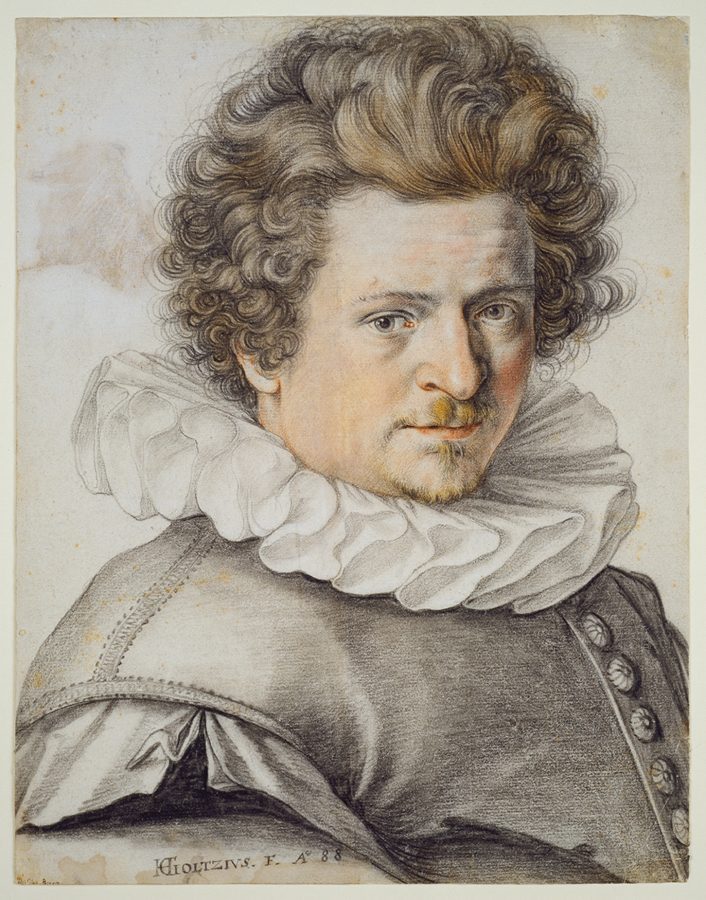

During the first half of the 1590s, Hendrick Goltzius created several large colored-chalk portraits of his artist friends, as well as two self-portraits. Mid-career, he traveled from Haarlem to Italy, encountering drawings and oil paintings that suggested new possibilities for employing color in portraiture. Already renowned as a graphic artist, Goltzius began to refashion himself as a master of color. I argue that these brilliant drawings provide valuable insight into his transition from linear expression to full-fledged oil painting in 1600. Equally important, they demonstrate an expansion of his technical prowess, using colored chalks (and washes) to evoke the presence and personality of sitters, especially through glowing flesh. Taken as a group, these presentation drawings gain resonance by representing a community of artists, bound by friendship and profession.

Wondrous Drawings

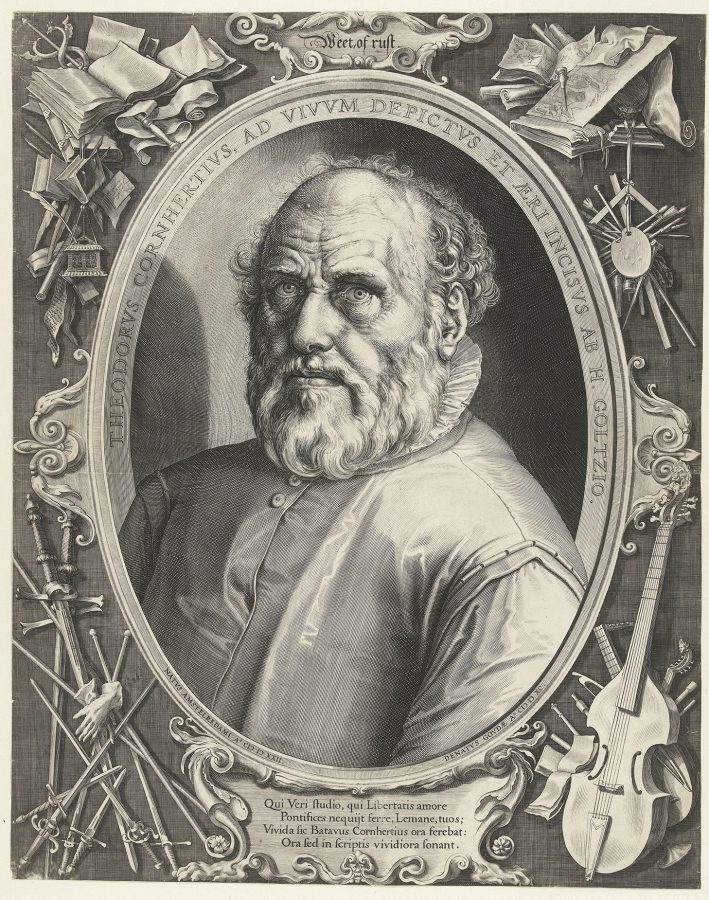

In his Vite of 1642, the artist Giovanni Baglione (1566–1643) expressed his astonishment over the mimetic virtuosity of the colored-chalk portrait drawings by the Haarlem artist Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617), which he had seen in Rome. The “most wondrous” technique shown in these sheets appeared all the more extraordinary from the hand of a much-admired engraver: “[Goltzius] took great pleasure in painting and made beautiful portraits; and in Rome he portrayed various talented friends, making, among others, sheets with touches of colored washes most wondrous [exceptional]. And along with others, he did a portrait of Francesco Castello from Flanders . . . so that he seemed alive, so well was he represented.”1

Baglione’s confusion about the mediums used by Goltzius is understandable. He ascribed the sheets’ remarkable effects to Goltzius’s use of colored washes rather than the chalks that contributed so significantly to the artist’s expression. Intuitively, Baglione recognized that Goltzius had blurred the distinctions between mediums. Goltzius’s large portraits of artists on paper were painterly images whose nuanced handling of color made the sitters seem to breathe. These drawings that Goltzius produced during his Italian trip of 1590–1591 and just after—autonomous presentation sheets rendered in dry colors, with added wash, rather than in oils—aided his transition from linear modes of expression to full-fledged oil painting by 1600. The novel lifelikeness of the portraits surely dazzled their subjects, Goltzius’s fellow artists, just as they later impressed Baglione. In the process of producing them, Goltzius began to craft a new image of himself as a master of color in chalks, an important step on the winding road toward mastery of oil painting.

In the biography of Goltzius that Karel van Mander published in his Schilder-Boeck of 1604, he noted that “when [Goltzius] drew something, then the flesh parts in particular had to be colored with cryons [fabricated chalks], and thus he eventually proceeded to brushes and oil paint.”2 Van Mander’s remarks echo a longstanding recognition of the significance of color in oil portraiture (and, by extension, in portrait drawings), for it enhanced the impression of lifelike immediacy in ways that line and volume alone could not. Indeed, many of Goltzius’s artist portraits leave the sitters’ bodies sketchy, in black chalk lines alone, which calls attention to the flesh above, one of the most difficult surfaces for an artist to depict.3 Goltzius was not the only portraitist to achieve such immediacy with chalks, but he handled them as no one else had.

The Artist Portraits

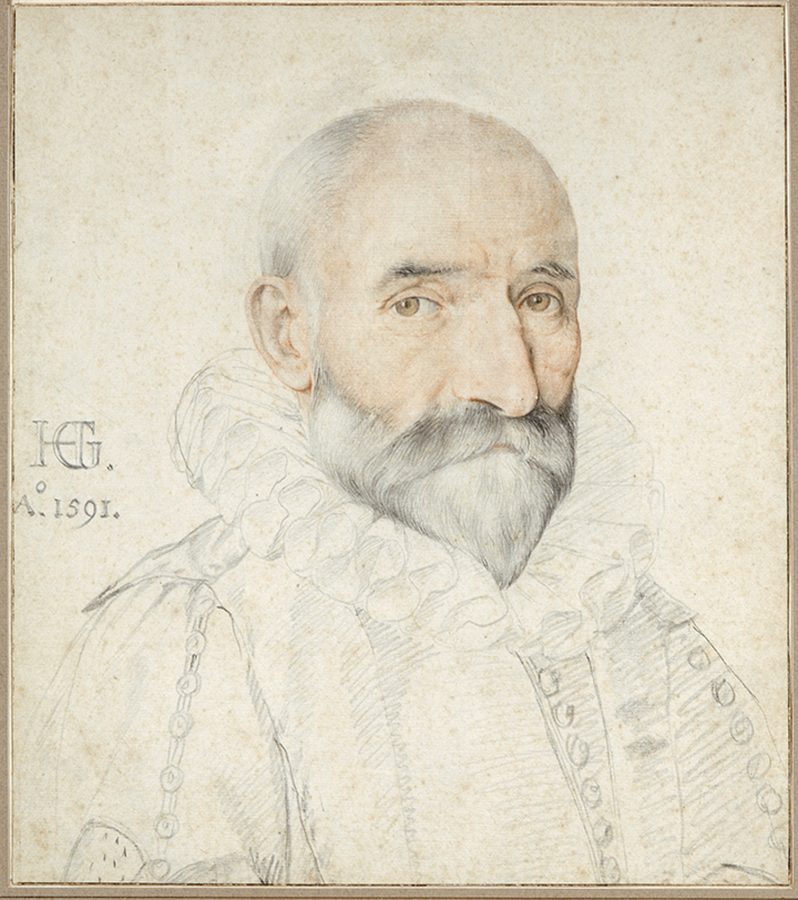

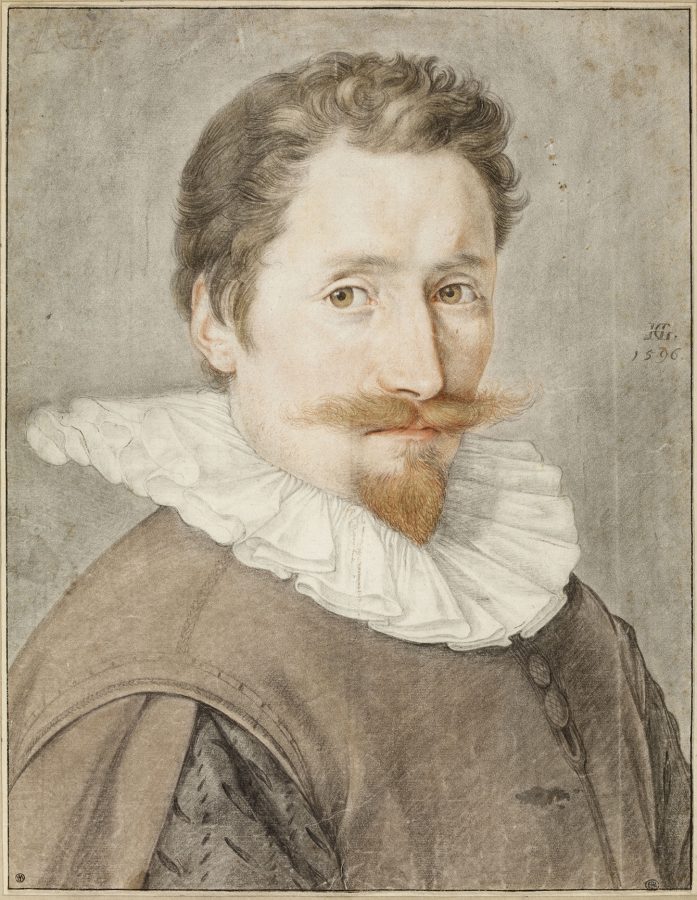

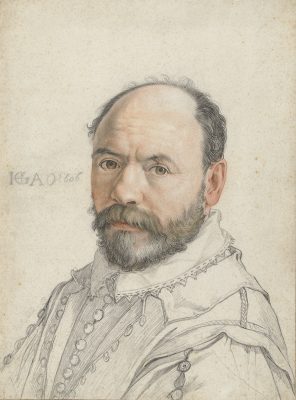

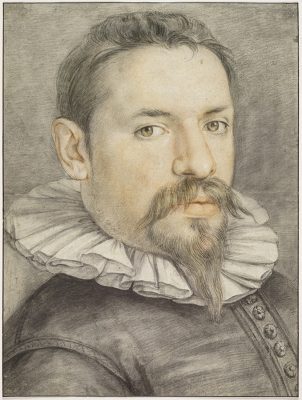

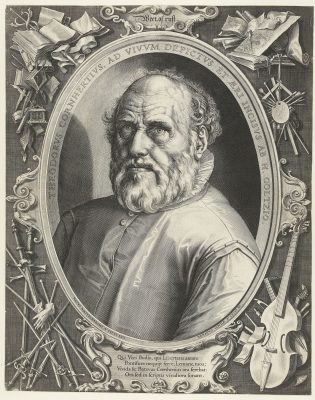

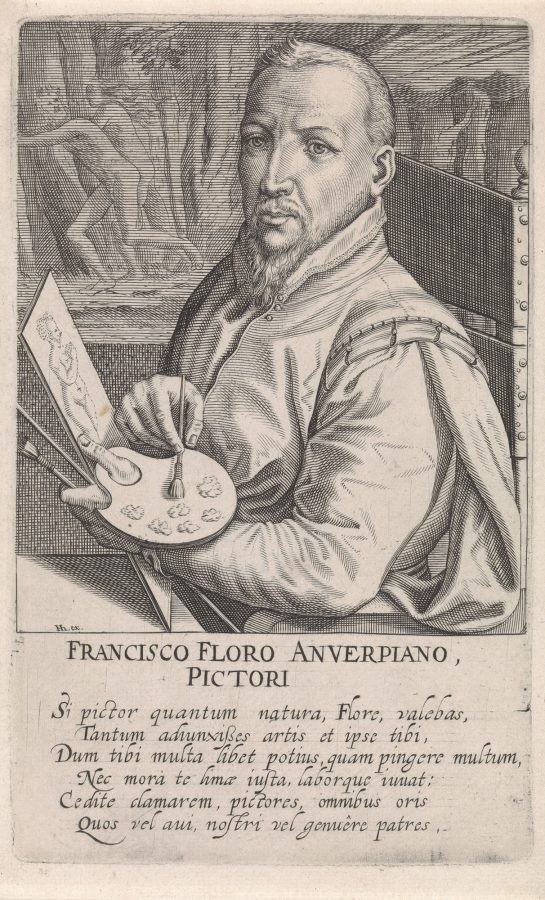

In 1590, upon his departure for Italy, Hendrick Goltzius was already an established graphic artist in Haarlem, widely admired for his draftsmanship. In Venice, the first leg of his journey, he adopted chalk and touches of watercolor for a portrait drawing of his Dutch friend and colleague Dirck de Vries (1558–1617) (fig. 1). After stops in Bologna and Florence, he next visited Rome and stayed for half a year. Although no portraits are known to have survived from this period, Van Mander claimed that Goltzius made one of the Roman history and landscape painter Girolamo Muziano (1532–1592) (unlocated), and a sheet in Weimar has sometimes been thought to portray Francesco da Castello (Frans van de Casteele, ca. 1541–1615) (fig. 2), the Flemish expatriate painter of miniatures to whom Baglione referred.4 During Goltzius’s briefer stay in Florence, he made a well-known portrait of the sculptor Giambologna (Jean de Boulogne, 1529–1608) (fig. 3) and another of the sculptor Pietro Francavilla (Pierre Francheville, 1548–1618) (fig. 4), along with a rendering of the painter Johannes Stradanus (Jan van der Straet, 1523–1615) (fig. 5), all three of them Flemish expatriates. Back in Venice, en route home, he drew the Italian painter Jacopo Palma il Giovane (ca. 1548–1628) (fig. 6). In Munich, the Flemish engraver Johannes Sadeler I (1550–1600) (fig. 7) and the painter Christoph Schwarz (1545–1592) (unlocated) sat for portraits. Several further extant drawings include an unknown man (fig. 8); Goltzius’s stepson, engraver Jacob Matham (1571–1631) (fig. 9); and goldsmith Johan Dideringh (active late sixteenth century) (fig. 10). Both during the trip and/or afterward, Goltzius also demonstrated the powers of color in his self-portraits now in Stockholm (fig. 11) and Vienna (fig. 12). Certainly, he produced more colored-chalk portraits than the number known today.5

Previously, I have written about why Goltzius made these drawings, arguing that they served principally as friendship portraits, produced on Goltzius’s initiative, either as reminders of his personal encounters or as gifts.6 This essay focuses on the inextricable interdependence of his subject matter and choice of medium. It discusses Goltzius’s materials and techniques, placing his use of dry (and some wet) mediums in its sixteenth-century context and examining its implications for his development as an artist. It asks about the meanings, professional and personal, that these materials may have carried for an artist embarking on a portrait compendium of artist friends.

In launching such a compendium, Goltzius might possibly have had in mind the example of Albrecht Dürer’s (1471–1528) metalpoint friendship portrait of Lucas van Leyden (1494–1533), which Van Mander claimed elicited a portrait of Dürer by Lucas in return.7 We might even imagine that Goltzius gained something material from the exchanges: say, a self-portrait by one of these artist friends or an amity portrait of himself by one of the chalk portrait sitters. If so, these are long lost. All we know for certain about the impetus for these works is that Goltzius made the portrait of Johannes Sadeler (see fig. 7) for his friend Philips van Winghen, as discussed below.

By focusing on likeminded practitioners, among them many expatriate Netherlanders, Goltzius essentially created an imagined community of artists on paper, his “talented friends” (to use Baglione’s expression). These were professionals well aware of Goltzius’s expertise and reputation back home.8 In return, he depicted them as colleagues whose talents had promoted their success on Italian and German soil. This fellowship of perceptive, appreciative, and knowledgeable viewers extended to liefhebbers (art lovers), the small circle of connoisseurs and likeminded beholders of the drawings who were not necessarily artists themselves. Jan Piet Filedt Kok has written about the international network of artist friends around Goltzius who engraved amity portraits of each other in the 1580s and throughout the 1590s—that is, portraits whose chosen medium, engraving, enabled replication and thus ensured ample distribution.9 Goltzius’s chalk portraits, by contrast, because they were dependent on color as their primary means of communication, could not be duplicated and were thus inherently limited in their circulation.

Chalks, Cryons, and Color

Sixteenth-century Netherlandish artists largely preferred pen and metalpoint to black chalk.10 In Italy, by contrast, artists had worked in black chalk for generations. Colored chalks—red chalk in particular, which was valued for its subtlety and friability11—were also more commonly used in the south (and in Germany) than in the Netherlands. Natural chalks are mineral substances, mined and cut into sticks from schist, hematite, other natural substances.12 Although red chalk was readily available in various hues, other naturally occurring colored chalks might have been more difficult to acquire, and their hues, purity, and intensity varied considerably. It is not surprising, then, that sixteenth-century Italian artists, including Federico Barocci (1535–1612), made their own drawing implements by mixing not just powdered hematite but powdered pigments of all sorts with binding mediums and compressing them into sticks.13 Many of the recipes became closely guarded secrets. Since fabricated chalks could often achieve a wider range of intensities and tonal nuances than natural chalks, they were worth the effort.14 Decades before Barocci, Germans such as Hans Burgkmair (1473–1531) recognized the vivacity that an intensely colored chalk could provide (fig. 13).15

Van Mander confirmed Goltzius’s adoption of fabricated chalks when he specified cryon (fabricated chalk) rather than krijt (natural chalk) as the medium for his large portrait drawings: “[They] continued to Rome on foot where he was recognized . . . by the artists there, the greatest of whom he portrayed in Cryons, as he also did in Florence, Venice and in Germany.”16 By cryons he probably meant fabricated chalks that had been compressed into pennekens (rods). In Den Grondt der edel vrij Schilder-const, the first section of the Schilder-Boeck (1604), Van Mander differentiated this fabricated cryon from krijt, the latter being a natural chalk cut into sticks, and I follow that distinction here.17 Likewise, the mid-seventeenth-century Dutch writers on technique and mediums Cornelis Pietersz. Biens, in his short treatise of 1636 De Teecken-Const,18 and Willem Goeree, in Inleyding tot de Al-ghemeene Teyckenkonst (Middleburg, 1668, 1670) singled out fabricated cryons.19

Terminology regarding friable, colored drawing mediums, both in the seventeenth century and today, is imprecise and confusing. It is often unclear from examining certain works whether a given passage was produced by fabricated cryon or by natural chalk. Indeed, certain colors may sometimes have been brushed in with watercolor.20 Nevertheless, in early modern sources, no doubt exists that from the later sixteenth century well into the seventeenth, Italian, French, German, and eventually Dutch and Flemish artists spent significant effort in finding the most suitable mixtures of pigment, binder, and (possibly) filler for their cryons.21 Later on, once the recipes had become settled and commercial availability of colored sticks common, pastel (the term adopted eventually for fabricated chalks) took on a life of its own as an alternative to oil paint in “painted” portraiture. Samuel van Hoogstraten anticipated this conventionalization in his Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst (1678), encouraging readers to work up a drawing “with red chalk and [fabricated] kryons, almost like painting with colors.”22 The medium attracted anyone who desired a dry technique that lent itself to creating effects, ranging from the highly finished to sketchy and vaporous.23 Sixteenth-century artists, though, whatever their choice of implements and mediums—whether chalks alone, chalks blended with washes, or natural chalks and fabricated cryons together—showed a new awareness of the growing market for colored drawings, especially portraits, as autonomous, collectible sheets.24

Although we cannot with confidence determine where Goltzius learned recipes for the fabrication of cryons, this matters less than Goltzius’s transformation of his predecessors’ work in this medium during his trip abroad.25 Whatever techniques he may have absorbed from previous chalk drawings in the North, in Italy he made the medium entirely his own.

Goltzius in Haarlem

Chalk was hardly an obvious choice for Goltzius. An accomplished printmaker, he had long suggested plasticity and devised bravura effects with fine, hard, calligraphic strokes. In drawings made before his departure south, he showed a preference for metalpoint in portrait drawings (figs. 14, 15, 16) and pen and ink (and sometimes metalpoint) for drawings preparatory to engravings.26His experience with color was relatively limited, though in a drawing of a lumpsucker dated 1589 he must have realized the advantages of combining black and red chalk with washes for depicting a living creature from life (fig. 17).27

We have reason to assume that Goltzius was aware of French and German artists’ explorations of colored dry mediums for portraits. French artists had long used black and red chalk for their drawings, among them Jean (1480–1541) and François (ca. 1510–1572) Clouet.28 They employed black and red chalk repeatedly for large-scale preparatory drawings for their painted court portraits, laying in the form in black and adding warmth with red for flesh (fig. 18).29 In this regard, they resemble drawings of high-ranking patrons by Hans Holbein (ca. 1497–1543), with which they share the combination of finished head, sketchy body, and an almost iconic formality.30 But Holbein’s portrait drawings use line more insistently to define facial contours, and he employed colored chalks more extensively (fig. 19). Notably, Holbein reserved colored chalks only for portraits. Although we do not know if Goltzius saw any of these drawings, he may have heard artist-talk about Holbein’s linear mastery in relation to color in portraiture and about the ways color could make heads come alive.31

Goltzius’s first really ambitious use of chalks came with a carefully worked-up portrait of his fellow printmaker and workshop assistant Gillis van Breen (ca. 1560–after 1602) (fig. 20). Goltzius probably chose a similar approach for the now-unlocated drawing of his teacher Dirck Volckertsz Coornhert (ca. 1591–1592) in 1590.32 Presumably this sheet stoked his memory when he memorialized him in an exceptionally large and vivid engraving of 1591–1592 (fig. 21).33

Van Breen was the ready subject for portrayals in all sorts of mediums, among them metalpoint, pen and ink, chiaroscuro woodcut—and now chalk.34 The chalk portrait shows Goltzius exploring a transition from hard line to soft chalk—or rather, to relatively soft chalk, for he sharpened the implement to a fine point. Evidently, he still conceived of the head in terms of line. Note the calligraphic swirl of curls he invented to capture Van Breen’s exuberant head of hair, as well as the linear finish of his collar and doublet. Unsurprisingly, Goltzius began with an overall black chalk substructure, though he did draw the first contour lines of ear, nose, and mouth in red. He added red to further simulate skin tones; a little yellowish brown in the hair, mustache, and chin stubble; and shadowed effects near the eyes and right cheek. The subtle interplay of shadows and reflections is reminiscent of his portraits in metalpoint, a medium that encourages intricate shading. Here in the chalk drawing, he achieved tonality by hatching and stumping. In fact, the drawing gives the appearance of an engraving-cum-color, with the skin in particular dominated by linear rather than coloristic description.

Goltzius in Italy

Once Goltzius reached Italy, he would have encountered not only individually colored portrait drawings by prominent artists but also a theoretical orientation to prompt his further exploration. Goltzius traveled to cities—Venice, Bologna, Florence, Rome—where drawings were considered an ideal medium for working out the power of color to evoke human personality. Significantly, portraits count as the single biggest category of these colored-chalk drawings. Thomas McGrath has written extensively about sixteenth-century ideas concerning color’s role in expressing intangible qualities of character and likeness.35 Gian Paolo Lomazzo, writing in 1585, saw color as expressive of a person’s “voice and spirit, because in representing the complexions, [the artist] paints in their faces melancholy, anger, happiness and fear.”36 In his L’Aretino of 1557, Lodovico Dolce articulated the connections between color and mimesis, emphasizing the power of flesh in particular to simulate life: “Coloring is so important and compelling that, when the painter produces a good imitation of the tones and softness of flesh and the rightful characteristics of any object there may be, he makes his paintings seem alive, to the point where breath is the only thing missing in them.”37 Many of these ideas would have had resonance for a Netherlandish artist such as Goltzius, grounded in an artistic culture that valued the role of color in infusing depictions of the human body, especially glowing flesh, with life.38

As for Goltzius’s exposure to individual artists, his acquaintance with the work of Federico Zuccaro (1539–1609) is assured. According to Van Mander, Goltzius visited him in Rome,39 where he would have had the opportunity to see Zuccaro’s two-color drawings on paper. Throughout his career, Zuccaro had employed red and black chalk for figure studies preparatory to paintings and for small portrait drawings that functioned as finished sheets.40 Zuccaro’s portrait drawing of Giambologna (fig. 22) exemplifies this technique.41 Vigorously drawn lines include hatching in red for the flesh or black for the body. In contrast to this striking openwork approach for the entire figure, the red and black chalk technique that the Clouets and Holbein preferred for their heads seems delicate and refined.42

Correggio (1489–1534)—whose paintings, Van Mander notes, attracted Goltzius’s attention in Rome—also exploited red chalk for its painterly advantages. His approach approximated the warm tonal range of his paintings. Correggio preferred white heightening (and occasionally black ink) as supplements to red chalk, at least in extant drawings, though Bellori claimed that for his heads, Correggio worked with pastelli (all sheets of which are unlocated), by which he meant fabricated chalks.43

While Zuccaro only rarely ventured further than the two-color medium in drawing, many other Italian predecessors and contemporaries embraced polychromy for painterly textures, flesh tones, and/or atmospheric effects in their works on paper. In the early sixteenth century not only Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) but also Francesco Bonsignori (1460–1519) produced impressive portraits in colored chalks (fig. 23).44 In the later sixteenth century, Federico Barocci (1535–1612) was the most innovative of the Italian draftsmen using color. Although Barocci employed some brown washes, he preferred the fabricated sticks that Bellori termed “pastelli” alongside natural colored chalks.45 By the time Goltzius arrived in Italy, Barocci’s colored drawings likely circulated fairly widely.

Goltzius’s Initial Italian Portrait

Before his departure for Italy in 1590, metalpoint had served Goltzius’s needs for presentation portrait drawings because of its capacity for fine detail, subtle tonality, and intrinsic preciousness. Indeed, he had pushed its limits as far as he could (see figs. 15 and 16). Once in Italy, Goltzius began showing off his aptitude for technical invention in a different way, by exploring mediums—chalk and watercolor—that he had only sampled earlier. The first of Goltzius’s Italian portraits, Portrait of Dirck de Vries (fig. 1a), signals the change.

Dirck de Vries shares certain characteristics with many of Goltzius’s Haarlem metalpoint (and engraved) portraits. The same compositional schema is evident: half torso, the body turned to the left, the head en face. But in Venice, Goltzius had little use for the high-class dress that rendered his Haarlem portraits formal, the burin-like line, or the small scale. De Vries’s body is sketched in light, loose, black chalk strokes. The large size of the De Vries sheet is comparable to that of the Van Breen portrait (fig. 20a), not to mention the French and German drawings that came before them (see figs. 13, 18, and 19). Goltzius’s metalpoint portraits, especially, often less than a third this size, seem like miniatures in comparison.

The De Vries portrait’s immediacy is conveyed by two innovations. First, Goltzius conceived of the head in terms of color, laid in with red chalk more fully than in Gillis van Breen. Shades of red, aided by some red watercolor, shine through everywhere except at the top of the cranium, suffusing the head and face with subtle warmth. While artists before Goltzius, such as Burgkmair, had also begun portraits with red chalk, they immediately pinned the drawing down with black line, often in some other medium. The Clouets simply heightened the flesh with light tints of red, adding color to otherwise monochrome drawings. By contrast, Goltzius smoothed the light black upper layer as well as the underlayer of red using an approach that, later, Willem Goeree termed reuselen, so that the hatching is barely visible.46 Second, Goltzius worked in another warm hue, yellow-brown natural chalk or fabricated cryon, for the mustache and several hairs in the otherwise graying beard. Highlights in opaque white watercolor also appear throughout the face, lending sheen to the skin that complements the play of reflections prominent in the turned-away side. This impressive technique is worthy of its artist-subject, a fitting tribute to an artist-friend.

Further Exploration of Colored Chalks

Rome was the next leg of Goltzius’s trip, and during the months he spent there, work with chalks consumed many a productive moment. His materials of choice for the numerous drawings he made of antique statuary were red and black chalks, but he employed each color alone, never mixing them. Chalk’s usefulness had to do with its ease of manipulation and versatility. He could employ it broadly to render volume, plasticity, overall harmony, and generalized light effects, or he could sharpen the stick for insistent contours and detailed surface textures.47 This practice of using chalk for sketches and finished drawings alike carried over into his portrait drawings. While the format of these sheets remained constant—worked-up heads with sketchier torsos—his color choices and technique evolved.

Of the extant drawings Goltzius executed in Florence, on his route back north, Portrait of Giambologna (fig. 3a) is the best known—for its plasticity of form, nuanced handling of light and shade, and striking juxtaposition of a finished head with sketchy garments.48 The rough bravura of the long slashing strokes of black chalk in the clothes—continued, for the first time, in hatched strokes hinting at space behind the figure—make the refined head, subtle in color and detailed in line, appear all the more alive. To achieve that refinement, Goltzius added touches of watercolor to the red, black, and white chalks (whether natural or fabricated).49 He played the fine lines of the hair and wrinkles off the glowing color of the complexion in a freer manner than in De Vries’s portrait.

Perhaps he imagined this sheet in competition with Zuccaro’s 1575 portrait of the same sculptor (fig. 22a), a drawing that twists the body to suggest lively movement. The two sheets show varying ways in which enhanced pictorial means could achieve a painting-like immediacy. Zuccaro’s added color appears as embellishment and notation; he even used the same red for the clay bozzetto (sketch) as for Giambologna’s skin and lips. But for Goltzius, red chalk was fundamental to his conception of the figure as conveyed through skin tones and minutely described facial detail. Equally important, in juxtaposing the finished head with a sketchy body—in contrast to Zuccaro’s relative consistency of handling—Goltzius showed off chalk’s capability in both modes, as well as his own virtuosity with the medium. The clothing and background reveal a vigorous, gestural hand, while the face features delicate line and subtle applications of color. Emphasizing how the hand creates strokes, Goltzius sketched the clothing and background; suppressing his handmade strokes in the head, he allowed color to do more of the work.

Portrait of Pietro Francavilla (fig. 4a) renders the Cambrian sitter as dignified but less insistently magisterial than Giambologna. This was appropriate to Francavilla’s more modest position in the Florentine hierarchy of sculptors. Gazing steadily and intensely outward, the sitter comes alive as a fully three-dimensional individual.50 The sheet’s brilliant state of preservation lets us see the subtle means by which Goltzius conveyed Francavilla’s complexion: his intermingling of light and shade for plasticity, his highlighting with white for skin composed of various hues and tones, and his delicate layering of gray and brown tones over red to achieve the effect of blood beneath the surface, emulating the glow that Goltzius so prized in Italian painting.51 Here more obviously than in any previous drawing, Goltzius blended the transitions with a stump and washes to smooth lines away (much as Van Mander recommended using a fanning brush for softening flesh in paintings).52 By now Goltzius may have recognized stumping’s capacity to make a sanguine-colored chalk appear as a lighter and warmer red.53 Perhaps the availability of differently hued reds in Italy also stimulated his creative impulse. Or perhaps grinding the red-hued pigments into cryons made the difference in allowing him to convey glowing flesh tones.

Two other extant Florentine drawings show Goltzius’s versatility in his handling of chalk portraiture. Portrait of an Unknown Man, sometimes identified as the Brussels painter Francesco da Castello (fig. 2a), is sparely drawn in red and black alone.54 The portrait of the Bruges artist Johannes Stradanus (Jan van der Straet) (fig. 5a), then in the service of the Medici duke, seems almost austere, combining paler black and red chalk with a little brown and gray wash. Compared to the portraits just discussed, both are relatively subdued in color and less bold. In emphasizing the finely boned head, angular beard, and sharply contoured nose, Goltzius acknowledged his sitter’s age (sixty-eight) and aristocratic demeanor. The work appears to pay homage to a life in art. By contrast, Unknown Man, in hard, pointed chalk, employs an assertive linearity to render a younger, energetic individual. The outward turn of the man’s head conveys the immediacy of an actual sitting and suggests a personal connection to the artist. If this sheet does portray Castello, its linearity perfectly suits this founding member of the Academy of St. Luke in Rome, whose few extant paintings espouse principles of disegno. Both portraits leave the impression that Goltzius matched the treatment to his measure of the men.

During Goltzius’s second visit to Venice, just before he left Italy to head home, he produced a portrait of Palma il Giovane (see fig. 6). The drawing of Palma, a prominent Venetian painter, is Goltzius’s only sheet of an Italian sitter to survive. (The portrait of Girolamo Muziano is unlocated; De Vries and the rest were expatriate Netherlanders). Here the slight lowering of the body on the sheet enhances the drawing’s informality. Goltzius sketched the jacket with such sureness of touch that the fabric suggests movement. He deepened and warmed the hair and beard with brown tones (in wash or, alternatively, chalk or cryon), rather than relying primarily on the yellow-brown chalk (or cryon) of the de Vries portrait.55 A few years later, Goltzius would express his admiration for Palma when he engraved a print after a design by the Italian artist, dedicating it to a friend.56 But here he expressed his admiration in color.

What I have called the “versatility” displayed in all of these Italian drawings could just as easily be called “exploration.” Since his earliest years, Goltzius had proved himself a master of disegno in the narrower sense of the term (drawing, form). He came to Italy an acknowledged virtuoso with the pen and burin, as well as an inventor of novel compositions with dynamic nudes, and he continued his mastery of line in the sketchy bodies of his sitters. But once there he delved into colorito (color, brushwork) in a most remarkable way, admiring firsthand the work of Italian painters and draftsmen and recognizing the importance of color in their imitation of natural appearances. In his most innovative Italian portrait drawings (see figs. 1, 3, 4, 6, and 11), color became integral to design.57

After Italy: Goltzius’s Portraits in Munich and Haarlem

Goltzius returned to the Netherlands by way of Munich, where he continued his compendium of artist portraits, drawing Johannes Sadeler I (fig. 7a), a Flemish engraver then employed by the Bavarian court. According to Van Mander, Goltzius also portrayed the Bavarian court painter Christoph Schwarz with colored cryons (now unlocated).58 Interestingly, the Sadeler portrait shows Goltzius handling chalk in yet another manner. He devised a relatively simple head structure, defined by strong outlines and subtle tonal gradations. Extensive stumping achieves a smooth expanse of unblemished skin (despite the sitter’s age of forty-one), enlivened only by yellow for facial hair and red for lips. The broad head sits aloft a rather schematic body topped by a stiff ruff collar, which is exactingly delineated rather than summarily drawn. The portrait’s masklike impassivity and psychological distance, echoing images by Holbein and the Clouets, emphasize courtly decorum and status. As mentioned above, this portrait is also notable for the inscription on its verso, which reveals participation in the contemporary culture of gift giving: “Hans Sadelaer, expert engraver to the duke of Bavaria drawn from life by the renowned Mr Hendrick Goltzius 1591 for his friend P. v. Wingen” (Wingen was Goltzius’s traveling companion in Rome and Naples).59

The year 1591 on the verso of Portrait of a Man in the Harvard Art Museums, though annotated by a later hand, was probably transcribed from the original when the sheet was remounted (fig. 8a). Whether the drawing—with its subtle, mature handling of the black, red, and ocher chalks, detailed delineation of the collar, and relatively finished doublet—dates from the Italian trip or right afterward is difficult to say.60

Once home in Haarlem, Goltzius continued to produce artist portraits, executing large colored-chalk drawings of his stepson, the engraver Jacob Matham (fig. 9a),61 and the Dutch goldsmith Johan Dideringh (fig. 10a).62 In both portraits, Goltzius brought the finish of the body more closely into alignment with the finished head than in the Italian sheets, reminiscent of his earlier metalpoint portraits and the portrait of Gillis van Breen (see fig. 20). And like the latter, the Harvard sheet and the portrait of Matham revert back to the hatching strokes familiar from before the Italian trip, though now looser and more nuanced.

Portraying friends and colleagues naturally spurs artist to reflect on their own sense of self—or, put differently, to create a pictorial reflection of themselves. Renaissance artists were cognizant of the ancient notion that friendship is a reflection of an alter ego.63 It is therefore no surprise that Goltzius, a highly self-aware artist who was transforming traditional materials and ways of working in colored-chalk drawings, turned his attention twice to self-portraiture in colored chalk on paper (see figs. 11 and 12). Neither is dated, although the complex shading, reflections, and finish of the Stockholm sheet (fig. 11a) bear such a strong relationship to the portrait of Francavilla (see fig. 4) that it might well have come from his time in Florence. Yet here Goltzius invested much more of his energy in the head. Against the robust plasticity of the head, the collar—rendered for the first time in white chalk—acts as an amorphous cushion rivaling Correggio’s and Barocci’s melting haze of chalk strokes. Here Goltzius shows a self-conscious juxtaposition of aesthetic manners that is particularly appropriate in a self-portrait. Once again, the surface of the skin is smoothed with a stump to create a painting-like effect. For the first time, he has brushed the paper with a light green wash, which complements the warm reds as another means of vivifying the skin. Along with various other examples of colored-chalk portraits, the Stockholm self-portrait could possibly have remained a while in Italy after Goltzius’s return to the Netherlands.64 The technique of this and others that Baglione saw firsthand was surely “wondrous” (Baglione’s word) by any Italian standard.

Almost certainly, Goltzius’s Vienna self-portrait was produced in Haarlem between 1592 and 1595 (fig. 12a). This sizable chalk drawing is the most ambitious of these post-Italy sheets and the only one with an oval format.65 The surface of the self-portrait reveals chalks touched so lightly across the skin area that the rougher texture of the paper is revealed, in contrast to the finish of the flesh in his earlier self-portrait (fig. 11a). The earlier self-portrait’s blur of white gives way here to a vigorously sketched ruff that captures the naturalistic flow of intricately folded cloth. The firmly delineated body and the sharp turn of the head in an opposing direction enliven the effect further.

Overall, in this self-portrait, Goltzius achieved a remarkable balance between color and line, and between sketchiness and precision. Perhaps he felt challenged by the scrupulous linearity of his own recently finished engraving of the late Dirck Volckertszoon Coornhert (fig. 21a), the humanist thinker, engraver, and Goltzius’s teacher. Their similarity suggests Goltzius meditating on their very intersubjectivity, the reflection of the self in the other. The two works are similar in their size, oval format, and atmospheric space. Both achieve an exceptional ad vivum effect. The print honors Coornhert by exhibiting the engraving skills he taught. By contrast, the chalk drawing demonstrates the enduring mastery of the student, but now with a whole new set of skills obtained through work with color.

The engraving of Coornhert probably relied on a now-unlocated colored-chalk preparatory drawing from around the year of Goltzius’s portrait of Breen (see fig. 20), which the Coornhert drawing may have resembled.66 Since then, Goltzius had traveled a remarkable distance, as the post-Italian self-portrait in Vienna makes clear. Note the self-portrait’s lively, willful collar, set against the stiff torso and starched ruff of Gillis van Breen. Note, too, the self-portrait’s subtle pictorial adjustment of tones throughout the head and background and the coloristic handling of flesh in contrast to the metallic sharpness of Breen’s whole form.

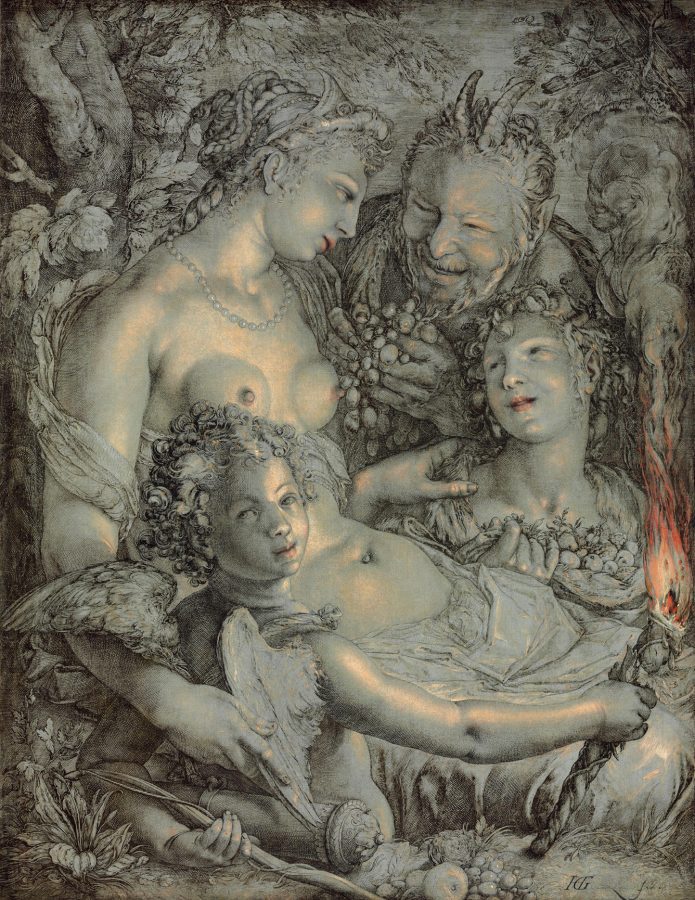

For the rest of the 1590s, Goltzius’s transition to oil painting was neither straightforward nor predictable. Once Goltzius was back in Haarlem, his restless artistic ambition took him in different directions altogether, most notably his Meesterstukjes engravings (1593–1594), some of which appropriated the styles of Italian painters that had attracted him on the trip. Other works, namely his famous pen drawings on canvas and parchment, demonstrate that he had not abandoned his mastery of line. But color was never far from his mind, as the most spectacular of the pen works on canvas, Sine Cerere et Libero friget Venus (Without Ceres and Bacchus, Venus Would Freeze), reveals (fig. 24). A tour de force of pictorial invention, this large canvas is enhanced by oil pigments.67 He touched colored paint over or alongside pen lines on a bluish-gray oil ground. In highlighted areas, the line gives way entirely to color, the source of the fiery warmth that keeps Venus from freezing. While hugely different in technique from the chalk (and wash) artist portraits, this bravura performance on canvas shares with them a fascination with challenging the boundaries between techniques and mediums and in revealing the enlivening effect of color. In making a statement about the power of color, this pen work played a similarly important role in Goltzius’s transformation from engraver/draftsman to painter.

In Friendship

Although various scholars have suggested that Goltzius may have intended to produce an engraved series of well-known artists, there is little reason to pursue this idea.68 These are, by and large, finished presentation drawings that, in their reliance on color for conveying personality and character, differed significantly from previous series on artists. No engraving, not even one with the coloristic detail of Portrait of Dirck Volckertsz. Coornhert (see fig. 21), could have done justice to their effects. In Goltzius’s time, the best-known engraved series of artist portraits was Hieronymus Cock’s publication of twenty-three portrait prints of deceased luminaries, Pictorum aliquot Germaniae Inferioris Effigies, each of which Dominicus Lampsonius provided with Latin poems (fig. 25). Here, image and text form a rather homogeneous, serial artistic identity, enhanced by formal and rhetorical devices—plinths, arm rests, hand gestures—to suggest the late sitters’ presences even in the absence of the makers’ physical encounters with their subjects.69 Goltzius himself had engraved portraits of several artists in the 1580s, including Phillips Galle (in 1582) and Johannes Stradanus (ca. 1583), which similarly erect framing devices to convey dignity, status, and intellect.

In their pictorial presentation, no less than in their differences each from the other, Goltzius’s new body of colored artist portraits differed significantly from Cock and Lampsonius’s, as well as from the sixteenth-century series of small, humanist portrait prints on which the latter was ultimately based.70 Goltzius’s chalk drawings functioned as individual sheets, separately conceived, finished, and (mostly) monogrammed, presumably for the delight of a limited audience of artists, art lovers, and friends, including Goltzius himself. Likewise, in contrast to the Cock/Lampsonius series, none of Goltzius’s chalk portraits refer specifically to the sitters’ artistic identity. The artists’ attire may be dignified—many wear that marker of class, the ruff, or a delicately lace-trimmed Italian collar—but Goltzius refrained from using devices that would present them either as members of an artistic workshop or as uomini illustri, that is, as members of an erudite, corporate whole, emphasizing status and public worthiness. The closest Goltzius comes to the latter is the inclusion of an oval medallion for his own self-portrait in Vienna (see fig. 12). This was added midway through, probably to echo his epitaph-like framing of his engraved Portrait of Dirck Volckertsz. Coornhert, to which his self-portrait acts as a sort of pendant. It is telling that Goltzius took that idea no further in this or any of his other chalk portraits. Instead, he stripped away all but the essentials, minimizing the physical and psychological barriers between sitter and artist, creating instead a dialogic encounter.

Goltzius’s artist portraits, with their striking shift in materials and approach, can be tied to his desire to explore all graphic mediums, show off his range of craftsmanship, refashion himself as an artist, and demonstrate the powers of his personal invention to evoke “nature in all her aspects”71 (in this case, the nature of the human head and face). At the same time, this new mode aligned perfectly with a revised conception of portraiture, defining it in terms of strengthened social bonds. Most early modern portraits functioned as agents of memory, keeping alive sitters’ features and spirit. But Goltzius went further, portraying artist sitters as individuals with whom he connected personally and professionally. His subjects appear as living artists, drawn before his eyes, on large-scale sheets of paper. Each of the sheets presents its subject looking outward toward the viewer, as if returning the gaze of a compatriot, whether artist or art lover. Rather than communications of status or public worthiness, they are (with the exception of Johannes Sadeler) evocations of personality and character. What better way to show his admiration for artist friends than by capitalizing on the color, texture, and softness inherent in chalks aided by transparent watercolor? This became his crucial aesthetic medium for imbuing warmth and vivacity. With these materials, he could exploit the essence of color, laying down line and color with just a few strokes and in the process producing not merely a wonderful likeness but a presence.

In 1590–1595, Goltzius’s full-scale embrace of oil painting was still several years away. Nevertheless, in these works on paper, he was able to use color to transform sitters into animate images beyond anything Netherlandish, French, German, or even Italian draftsmen had achieved. He created them by conspicuously choosing members of an artistic community abroad and at home—his fellow artists and himself—for his subject matter. In this highly experimental body of work, Goltzius the engraver/draughtsman had become Goltzius the painter in colored chalks.