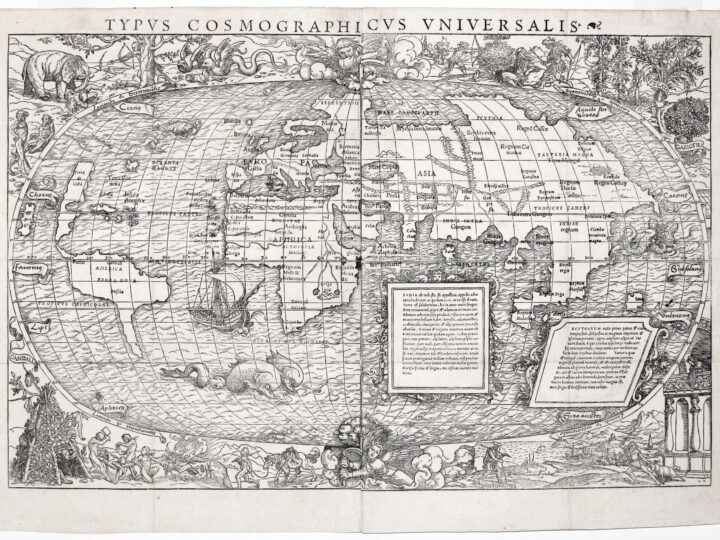

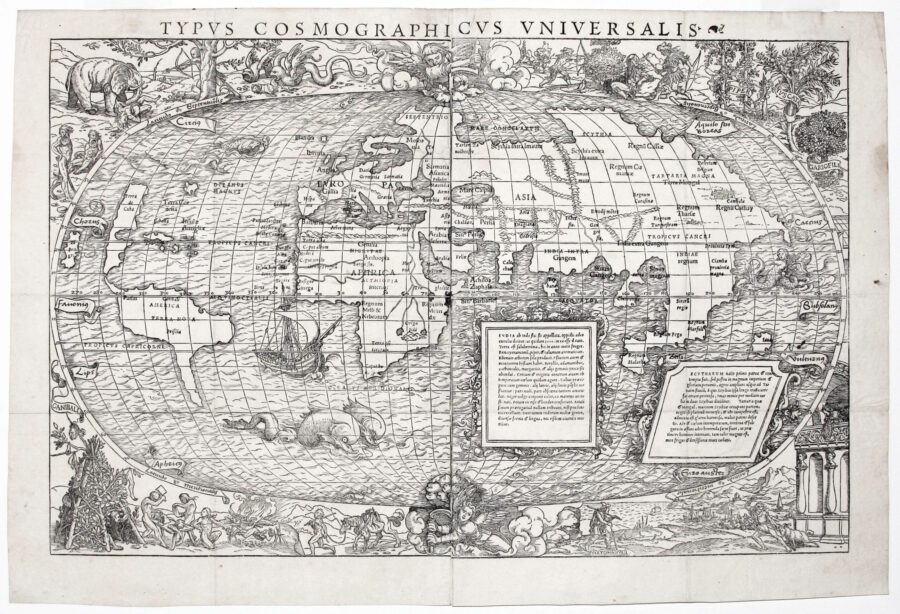

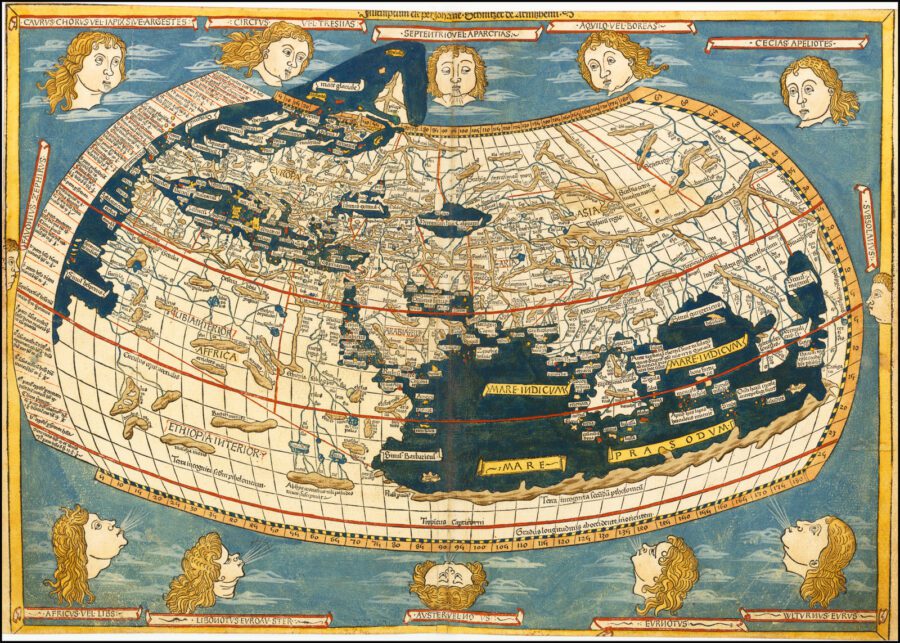

A 1532 woodcut map of the world, labeled Typus cosmographicus universalis, appears within a compendium of knowledge and travelers’ tales, Novus orbis regionum ac insularum veteris incognitarum (1532). It resulted from a collaboration between artist-designer Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1541) and polymath geographer Sebastian Münster (1488–1552). This article examines Holbein’s corner figural vignettes for their verbal and visual sources in ancient and medieval geographical traditions and in recent travelers’ tales, particularly publications stemming from American explorers, plus a recent illustrated Augsburg publication of Ludovico Varthema’s Itinerario to India. A final section addresses Münster’s mapping as a product of the revived ancient global projection by Claudius Ptolemy (second century CE) and how his collaboration with Holbein continued into his later maps and 1550 Cosmographia.

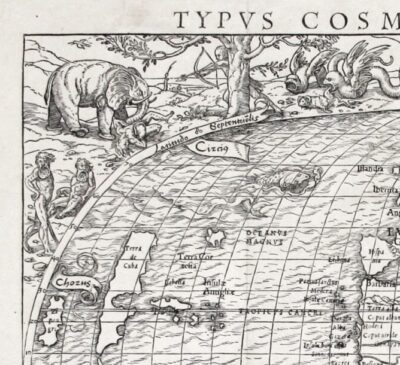

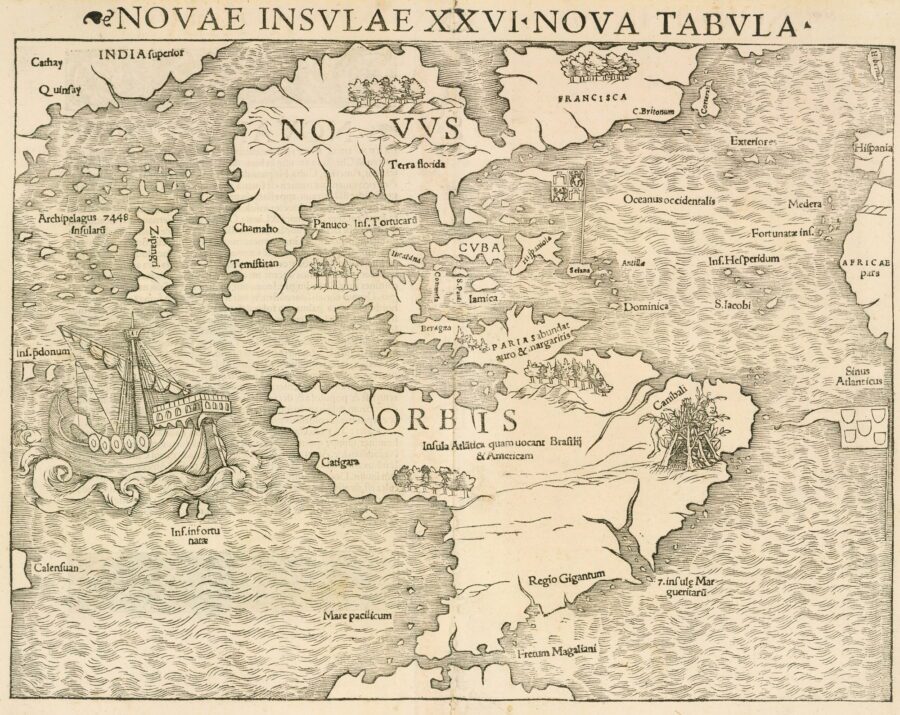

Modern students of cartography remind us that, particularly in the formative early modern years of maps, those printed images were compendia of both knowledge and rhetoric, addressed to serve particular audiences.1 As prints, often with figuration, cartographic images contain much material of interest—and necessary attention—for art historians of the early centuries of printmaking. One of the first world maps that emerged from the major printing center of Basel, a global overview with corner vignettes (fig. 1), was designed as a woodcut by no less a master than Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1541). He provided its complementary figural scenes from each of the four continents in the corners of the world map. Much of this essay is devoted to explicating Holbein’s unlabeled images in terms of their verbal sources, elements of which inform the Latin texts on the map.

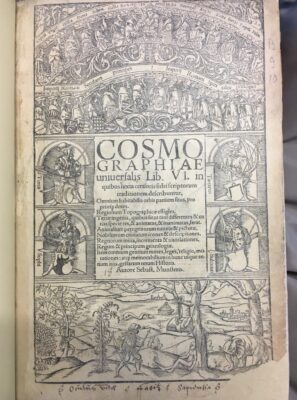

The Holbein images complement a map, titled Typus cosmographicus universalis (Universal cosmographic map), that consists of two sheets, to which additional frames with substantial Latin texts were added to its pictorial design. The mapping content of that global view, as well as the text in the frames, was the work of the polymath Sebastian Münster (1488–1552).2 It formed part of a book publication, Novus orbis regionum ac insularum veteris incognitarum (The new world of regions and islands previously unknown) (Basel: Johann Herwagen, 1532), a compilation of travelers’ tales assembled by Johann Huttich and Simon Grynaeus from Strasbourg that claimed to survey “the new world and unknown regions and islands,” including reports of the continents beyond Europe.3 That significant volume, in turn, anticipated Münster’s own eventual masterwork, Cosmographia (also published first in Basel, 1544; definitive Latin edition, 1550). However, the two collaborators on this world map never worked together again, since Holbein soon relocated to England and the court of King Henry VIII, where he spent the remaining decade of his career.

The figural scenes on this map hold special interest for globally minded art historians, coming at such a crucial early stage of European discoveries and travel stories. Incorporating both ancient and medieval geographical lore, these scenes present a visual summa of amassed contemporary knowledge.4 While most discussions of this 1532 map examine its emerging but imperfect knowledge of the New World, this study will examine the entire map as a true collaboration, containing a word-and-image mixture of inherited geographical concepts together with more recent explorations. Working against the habitual impulse in scholarship to see maps as increasingly scientific over time, this map bears traces of both its geographical sources and their limited knowledge while presenting a confident visual rhetoric of a globe-encompassing vision.

Two elements characterize the distinctive design of the 1532 Holbein-Münster map. Representative figures, featured in its four corners, provide active views of settings from each continent, but they also appear alongside the entire world, presented as an oval map, like a flattened globe. Holbein’s images, derived from textual sources, provide visual elements that disappeared from world maps of later generations, especially global maps in the first atlases, published by Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598) and Gerardus Mercator (1512–1594) in Antwerp during the 1570s.

HOLBEIN’S IMAGERY

America’s Cannibals

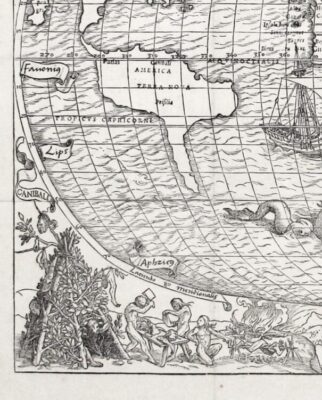

Despite his personal unfamiliarity with distant lands, Hans Holbein the Younger strove to provide up-to-date imagery of their inhabitants, drawn from the latest reports of their characteristic behaviors. As most commentators have discussed, the lower left section of his world map depicts native Americans as cannibali (fig. 1a).5 Here, beside a conical, lean-to shelter constructed from boughs and leaves, three naked individuals butcher a corpse (with a meat cleaver, though metal tools did not yet exist in the Americas before European incursions). Their table supports a human head and limbs, and their shelter, topped by another severed head, suspends a leg and hand. Beneath the curvature of the adjacent globe, Holbein also shows a roasting grill with more body parts, as a fourth naked man enters the clearing, leading a horse (an import from Spanish conquistadors) that carries yet another corpse, suspended limply from its saddle.

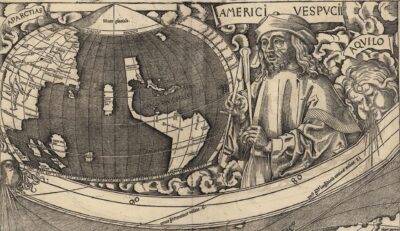

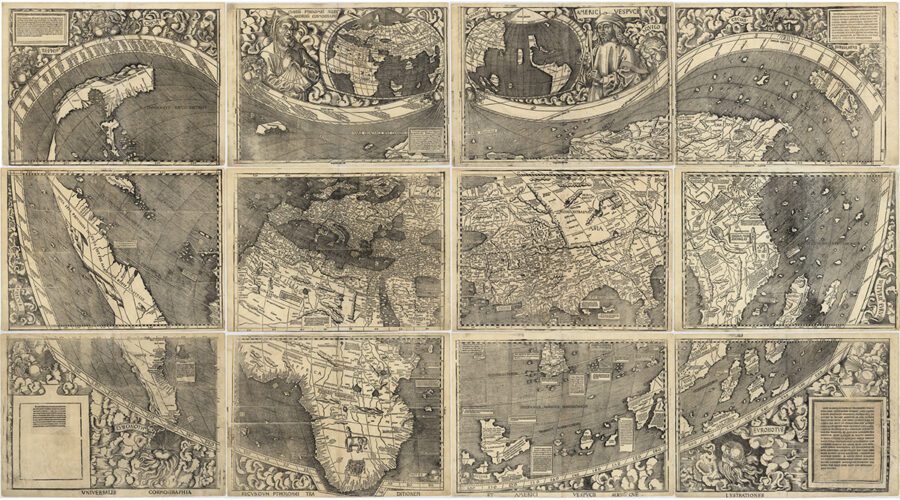

Early New World reports of cannibals, emphasizing their prevalent nudity and cruel violence, had already inspired lurid illustrations on woodcut broadsheets, those text-and-image newsletters of the early modern era, such as Albrecht Dürer’s familiar Rhinoceros woodcut of 1515.6 Accounts of New World cannibalism appear just after the turn of the sixteenth century, with reports about Caribbean peoples by Italian explorers Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) and Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512). Columbus’s diaries circulated widely as letters and were recorded through the publication of De orbe novo decades (About the New World) by Petrus Martyr d’Anghiera in Seville as early as 1511. A letter by Petrus Martyr appeared in Basel in 1521; a fuller text in 1533.Vespucci’s travels (and several descriptions attributed to him) circulated still more widely, often in European vernaculars with accompanying woodcut illustrations; moreover, his account was the first to link cannibalism to the natives in Brazil, especially in his Mundus novus (New World), first published by 1503.7 Among these purported Vespucci publications, the illustrated 1509 Strasbourg edition of Vespucci’s letter to Pier Soderini includes three woodcuts about a 1501 voyage that show hostile, naked natives dismembering bodies and attacking arriving European sailors (fig. 2). Based on such publications, when Martin Waldseemüller (ca. 1470–1520) first published his massive twelve-sheet world map in 1507, he not only named the entire new continent “America” after Amerigo Vespucci, but he also included a portrait of that explorer next to his western hemisphere at the top of his map (fig. 17a).8

Waldseemüller’s subsequent 1516 Carta Marina (Sea map) became the earliest printed map to illustrate New World man-eaters, which he identified by inscription as anthropophagi.9 He included an image of cannibals roasting and eating human body parts together with an accompanying caption: “Here is the most cruel nation of anthropophages (whom people call cannibals) which invade the neighboring islands,” and he added further details about mutilation and consumption.10

Legends of Americans as cannibals persisted much later in the century. These people typically were thought to occupy the interior of Brazil, a perception reinforced a generation later by a bestselling travel account by Hans Staden (German, ca. 1525–ca.1576), who wrote about his own perilous escape from Brazilian tribal cannibals in 1550. That book appeared with accompanying woodcut illustrations (fig. 3).11 Consequently, reports published shortly after midcentury by French travelers about the native Tupinambas had to address those cumulative inherited carnivorous expectations about Brazil. Superficial reports by Franciscan André Thevet (1558) and a later publication by his more critical rival, Calvinist Jean de Léry (1578), included purported eyewitness accounts of the Tupinamba in Brazil.12 Thevet, who spent only three months in Brazil, claimed that these Indigenous Peoples were “brute beasts,” naked and living “sans roi, sans loi, sans foi” (without king, without law, without faith).13 Léry, by contrast, offered a more ethnographic account, based on two years’ stay in Brazil, asserting that their cannibalism was a ritual vengeance, a ceremonial tribute to both captured victim and conqueror.

If Holbein’s image of “cannibali” offers a seemingly vivid representation of early sixteenth-century descriptions by travelers to the newly discovered “America,” it also builds on inherited concepts of cannibalism, reported earlier about other distant places far from European readers and viewers. Indeed, anthropophagi had previously been reported in both the steppes of Central Asia (Scythia) and Africa in medieval travel accounts, often increasingly fictionalized in direct proportion to their remoteness from Europe.14 Herodotus’s History (4.26, 1.216) provides a first European source for descriptions of cannibalism, including the disposal of older parents, a custom that he locates in the remote north among Scythian peoples. Later medieval authors associated similar bloodthirsty behaviors with Tartars (usually identified with warlike Mongols); however, Marco Polo’s account of his travels relocates that same practice to what he advanced as the even more distant Java.15

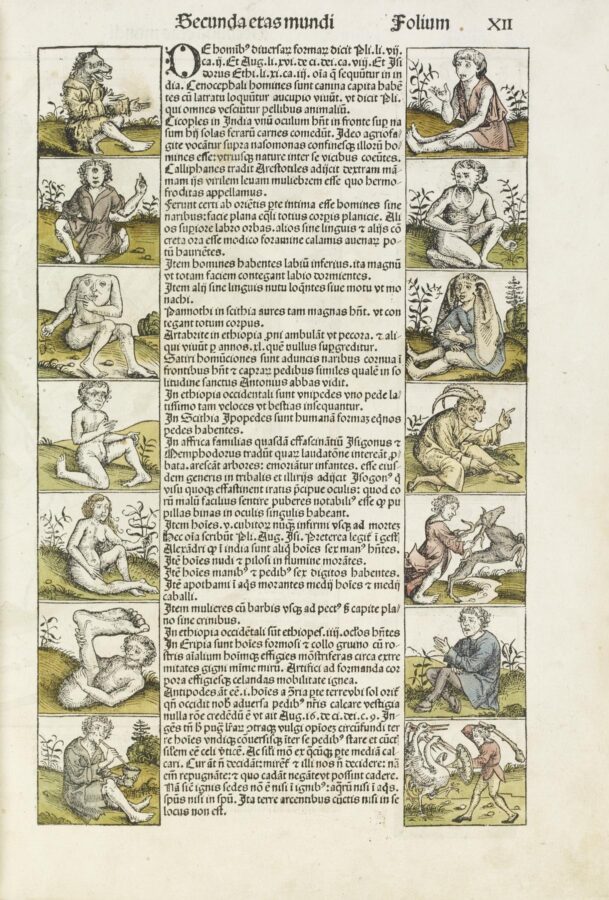

Many ancient and medieval travel accounts present an enduring roster of monstrous races, itemized by Pliny the Elder in his encyclopedic Historia naturalis (completed by 77 CE), Strabo (Geographica; first century CE) and Gaius Julius Solinus (Collectanea rerum memorabilium [A Collection of Memorabilia; 3rd century CE) and then afterward widely utilized in numerous medieval travel accounts of distant lands.16 The early sixteenth century’s contribution to this discourse was to project this ghoulish practice onto a new geographical entity, the fourth continent, specifically in Brazil and the Caribbean.

Columbus expressly reports in his diaries that he expected to encounter such monsters when he landed in the Caribbean, but instead he found only handsome natives: “In these islands I have so far found no human monstrosities, as many expected . . . except a people who eat human flesh.”17 Elsewhere, Columbus reported sightings of mermaids.18 Such reports held firm in a fictional afterlife. For example, Shakespeare’s Othello (1.3.142–145) speaks “of the cannibals that each other eat, / The Anthropopagi, and men whose heads / Grew beneath their shoulders”—the latter referring to the Blemmye, who were among the monsters itemized by Pliny the Elder.19

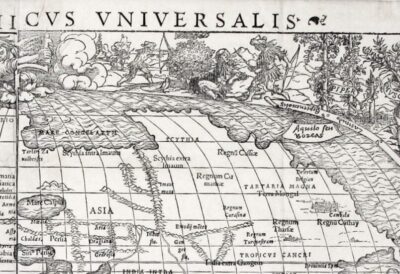

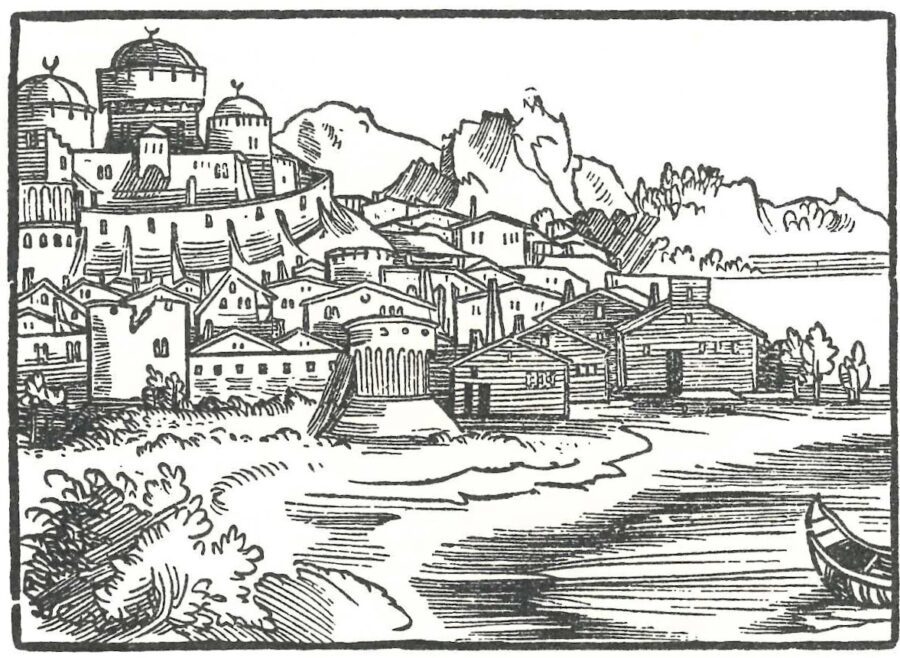

Asian Warriors and Spices

This same heritage of beliefs in distant Asian cruelty still pertains on Holbein’s world map, on the opposite corner of the world from his cannibali (fig. 1b).His marginal figures at the upper right include a pair of warriors, seemingly clad in feathers and carrying bows and a spear, wearing turban-like head coverings that identify them as Asians according to contemporaneous pictorial conventions. A third figure in similar dress lies on the ground at the foot of an approaching armed man. Whether he is a victim of an attack or an ally remains ambiguous, but this scantily dressed, warlike group clearly echoes medieval assumptions about bellicose Tartars or Scythians. In their northernmost positioning, the warriors at the top right of the map appear near those regions marked nearby on the map as “Scythia,” “Tartaria Magna,” and “Terra Mongal.”

Ironically, their rustic costumes with feather skirts also derive from early representations of Amerindians from the first woodcuts of the Americas, made by German artists to illustrate reports of the New World.20 Within an expansive woodcut frieze, the Triumphal Procession of Emperor Maximilian (fig. 4), Augsburg graphic artist Hans Burgkmair (1473–1531) repeated these feathered clothes while confusing the West and East “Indies,” since his figures, supposedly originating from India (“Calicut”), actually utilize the models from prior woodcuts of the Americas.21

In turn, these same costumes were also adopted for the peoples of Sumatra (fig. 5) in illustrations for a contemporaneous German translation (1515) of a recent account of travel to India, written by Ludovico Varthema of Bologna. These images stem from another Augsburg artist, Jörg Breu the Elder (1475–1537), who designed these Varthema woodcuts.22 Like Waldseemüller’s maps, both Burgkmair’s and Breu’s woodcuts in these recent German publications would have been readily available to Hans Holbein, who was raised in Augsburg but active by then in Basel.

Three labeled plants in the upper right corner of Holbein’s map follow the curve of the globe downward and southward to the equator, indicating this region as Asia. Their Latin names reveal that these flora are the sources of coveted spices from both India and Southeast Asia: pepper (piper), nutmeg (muscata), and cloves (gariofili), respectively. Such spices already formed the principal commodities of international shipping to Europe, beginning with the Portuguese. They prompted much commentary in medieval travel accounts.23 Marco Polo, for example, exclaimed: “There are in addition many precious spices of various sorts,” including both white and black pepper.24 Varthema also reported that nutmeg trees grew on the island of Banda, and he located clove production in the Moluccas (now the Maluku Islands, in eastern Indonesia) at “Monoch,” noting that the Portuguese began their trade there after conquering the emporium of Malacca, on the southern coast of the Malay Peninsula, in 1511.25

African Elephants and Dragons

On the upper left corner of Holbein’s map (fig. 1c) is a massive elephant, a longtime symbol of the continent of Africa—also present on the 1507 world map of Waldseemüller.26 Holbein shows a man shooting at the creature with his bow while the elephant tramples his companion underfoot.27 The verbal source for this scenario can be identified: a 1507 travel account by Cadamosto (Alvise da Mosto) of his exploration of the west coast of Africa, a text later incorporated into Münster’s Cosmographia. Cadamosto writes that “an elephant is an animal that does not attack man unless man attacks him,” like the situation depicted by Holbein. Cadamosto also claims that an elephant would respond with a mighty blow from its trunk to knock its assailant down. In Holbein’s image, beside a tree, two large, serpentine winged dragons look on; one of them is ready to devour a ram, which suggests their enormous scale. Here, too, Cadamosto provides the source, claiming that gigantic African dragons can “swallow a goat whole, without tearing it to pieces.”28 As late as the early seventeenth century, elephant lore, some of it derived from Pliny, still asserted that dragons lived “among the Aethiopians, which are thirty yards or paces long, these have no name among the inhabitants but Elephant-killers. And among the Indians also there is an inbred and native hatefull hostility betwixt Dragons and Delphants.”29

More distinctive still in the Africa segment of the Holbein map are the two naked humans, one standing and one sitting, who display enormous plate-like lower lips. They, too, come from Cadamosto’s account of men who were “very black in color, with well-formed bodies. Their lower lip, more than a span in width, hung down, huge and red, over the breast, displaying the inner part glistening like blood. . . . Their appearance is terrifying.”30 In fact, Mursi and Surma women in modern Ethiopia, recorded variously by classical authors Pliny and Strabo, still use such lip-plates, or labrets, made of clay or wood to expand their lower lips gradually until they can encompass a full-sized disc.

Such a figure appears among the “Marvels of the East” tradition of Pliny, among other monstrous figures who display enormous individual features, such as an extended ear or a giant single foot (Sciapods) that they use for shade in a tropical climate. These figures reappear with other Plinian monstrosities at the margins of the Ptolemaic world map in the 1493 Nuremberg World Chronicle (fig. 6).31 Jean-Michel Massing has discovered another possible image source for Africans with pendulous lips in an illustrated Strasbourg publication (1522, 1525) of the revived second-century ancient world map by Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria (ca. 100–170 CE), which, as discussed below, was a recovery of considerable importance for Renaissance mapmaking.32

Muslim Asia and Varthema

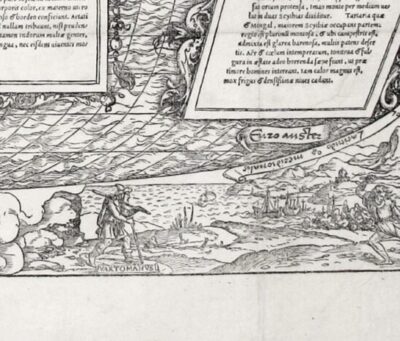

In the remaining marginal scene at the lower right of his map, Holbein shows an explorer wearing another turban-like cap as he advances rightward across a generic coastal landscape with ships in a harbor (fig. 1d). His dress turns out to be a disguise, and his destination is revealed by the label assigned to the traveler: Vartomanus. That name is a Latinized version of the Italian traveler Ludovico di Varthema, mentioned above. According to his travel book, Varthema used local costume to make his way to India by way of the Middle East. His first-person account, the Itinerario (1510), was the book published in Augsburg with Jörg Breu illustrations, Die Ritterlich un[d] lobwirdig rayß (Chivalric and praiseworthy travel, 1515).33 Indeed, Holbein’s landscape itself is loosely based, in reverse, on Breu’s imagined view of Calicut (fig. 7), a port city on India’s coast described in Varthema’s text. The domed building on a hill above the port, backed by mountains, is depicted in Breu’s woodcut as a mosque with a crescent moon.34 Varthema’s ambiguous costume in Holbein’s image derives from his necessary disguise as a Muslim Mameluke trader, which he had to assume in order to visit Mecca and other holy sites on his travels (Breu also illustrated his visit to the tomb of Muhammad in Medina). After imitating feathered costumes for Scythians or Mongols in northeastern Asia, Holbein here uses a turban to represent the southeast, expressly the east coast of the Indian subcontinent.

The final vignette in the lower right corner of Holbein’s map shows a scene before a fanciful palace, from whose balcony a nobly dressed woman looks on, while a youth in antique costume wields a club above a ram (fig. 1e). That scene, too, is based on Varthema’s account, an odd early moment when the traveler was detained in Arabia Felix (present-day Yemen) but was treated with kindness by the queen. Varthema explains that, while they were imprisoned, he and his Muslim companion arranged for him to appear insane for a three-day period. He acted out by seizing an enormous sheep (whose tail alone weighed forty pounds) and addressing it like a person, asking whether it was a Muslim creature. Then, Varthema recounts, “I took a stick and broke all its four legs. The queen stood there laughing, and afterwards fed me for three days on the flesh of it.”35 Posing an alternate reading, Jasper van Putten has identified this scene with a later moment in the same text, less filled with narrative details, in which Varthema comments on the enormous size of sheep and other animals in the country of Tarnassari: “And there is another kind of sheep, which has horns like an adder: these are larger than ours and fight most terribly.”36 What remains clear from the corner vignette on the lower right side of Holbein’s design is how he relied on both the text of Varthema’s travels plus Breu’s Augsburg illustrations to furnish the visual accounts for this southern quadrant of the eastern global hemisphere.

Printed Sources and Cosmology

Holbein and Münster’s 1532 map grew out of a verbal context of knowledge. Holbein visualizes literary accounts of faraway lands from a variety of sources assembled by Huttich and Grynaeus. Peter H. Meurer’s meticulous study itemizes seventeen sources, seven of which stem from a Portuguese text by Fracanzano da Montalboddo (act. 1495–1519), published in Vicenza in 1507 (with opening chapters by Cadamosto) and issued in Latin as Itinerarium Portugallensium (Portuguese itinerary) the following year. In 1508 a Latin version of the text by Cadamosto, Navigatio ad terras ignotas Aloysii Cadamvsti (Voyages to unknown lands), appeared in Milan in a translation by abbot Archangelo Madrignano. It was newly expanded along with intervening publications for a 1532 Latin edition.37 Montalboddo’s text also draws on Columbus, Vespucci, and the Portuguese explorer Pedro Alvares Cabral, among others. Another early German source also used Cadamosto’s German translation by Jobstein Ruchamer, Newe unbekanthe landte (New Unknown Lands). Thus the entirety of Cadamosto and Montalboddo was accessible in Latin by 1532 and reprinted in Basel by Huttich and Grynaeus. The ten remaining sources on Meurer’s list all incorporate Petrus Martyr d’Anghiera’s accounts of the New World.

A major precedent for the 1532 Latin volume by Huttich and Grynaeus was another earlier compilation of world descriptions, which also included Montalboddo and might have provided Holbein with travel stories: Joannes Boemus’s Omnium gentium mores leges et ritus (Customs, laws, and rites of all peoples). In chapter 8 of a 1555 English version of Boemus, Fardle of façions, a skeptical view emerges about earlier comments describing India, though it still mentions Plinian monsters, such as dog-headed men (Cynocephali, often characterized as cannibals), cyclopes, and long-eared men, plus one-legged Sciapods.38 Chapter 9 of Boemus discusses Scythia and accords well with Holbein’s imagery on the 1532 map. It also repeats earlier reports of cannibalism in that region, followed by a brief Chapter 10 on Tartary (northern Asia), “otherwyse called Mondal.”39

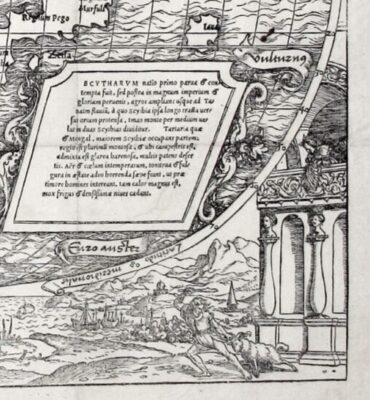

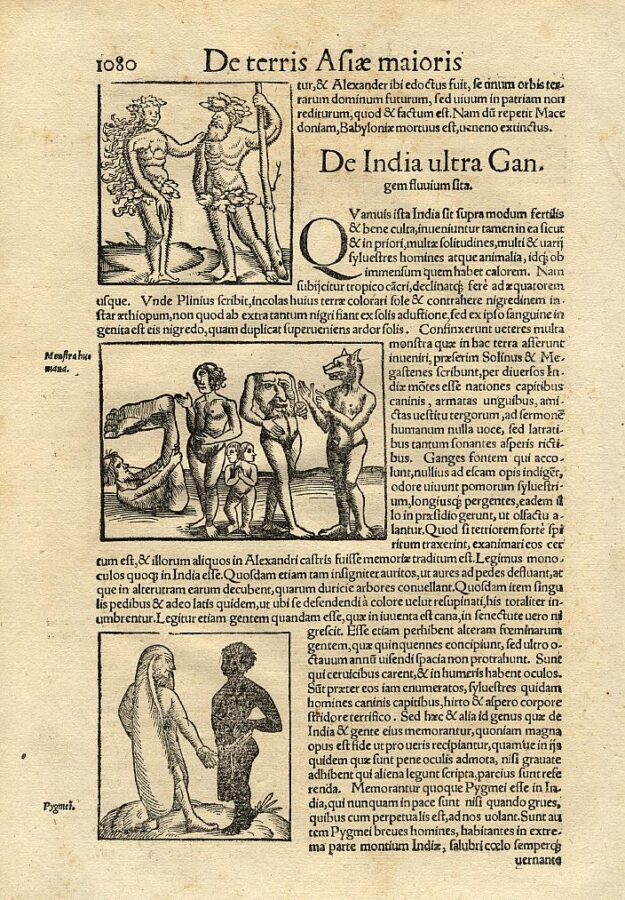

Yet Münster’s own Cosmographia also includes a woodcut image (fig. 8) of Plinian monsters, assigning their geographical region to India beyond the Ganges (De India vltra Gangem flvvivm sita [About India beyond the River Ganges]).40 On a single page he illustrates a Sciapod, a cyclops, a two-headed pygmy, Blemmye (a figure with its face in its chests), and a Cynocephalus (dog-headed man), as well as a second image showing a long-eared man standing beside a black-skinned man.41 At the bottom of the same page Münster verbally describes pygmies fighting cranes,42 a legend that goes back to Homer’s Iliad (3.1–9; as a simile for the advancing Trojans), and Pliny repeats the same image in his Natural History (4.18; 7.2). There Pliny expressly places them “at the extreme boundary of India to the East . . . in the most outlying mountain regions.”43

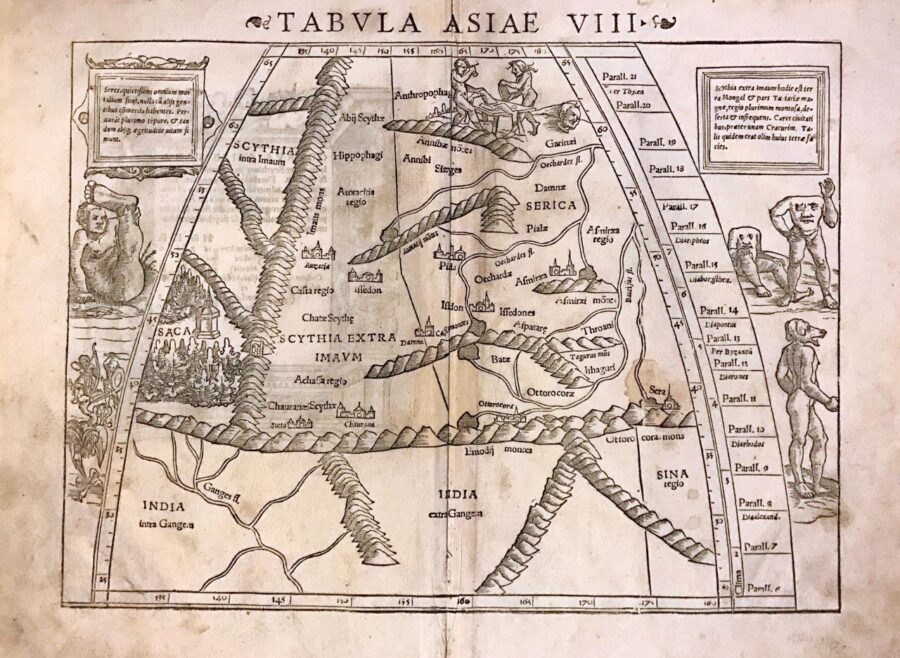

Münster’s own map of Scythia east of the Immaus Mountains, from his earlier 1540 Geographia universalis (fig. 9), shows cannibals butchering human victims with cleavers at the top of the map. In the margins at either side, he retains the Sciapod, Blemmye and Cynocephalus, but at the lower left, he also includes a combat between pygmies and what appears to be an oversized crane. This myth of pygmy-crane battles survived. Later in the sixteenth century it formed a scene within the print series of hunts, Venationes Ferarum, Avium, Piscium (Hunts of wild animals, birds, and fish; 1578–1599; 122 prints), designed by the Medici court artist at Florence, Johannes Stradanus (Jan van der Straet, from Bruges; 1523–1605) and engraved by Adriaen Collaert (1560–1618) for publication in Antwerp by the firm of Philips Galle (fig. 10).44

In addition to his corner figural vignettes, Holbein also inserted various sea creatures into the oceans of the 1532 map, though no such figures had appeared on Waldseemüller’s 1507 world map.45 Pliny’s Natural History had made the claim that “anything which is produced in any other department of Nature, may be found in the sea as well,” often in the form of hybrids, such as mermaids.46 Increasing numbers of distant seafaring voyages from Europe brought intensified attention to the oceans—though clearly this 1532 map could never be used for navigation, which comprised an entirely separate category of mapmaking.47 Below Africa, two dolphins fill an open space on the map. Such figures became clichés in sixteenth-century maps: decorative motifs on open oceans, easily overlooked as space-fillers but also functioning to anchor the matrix of either wood or copper during the printing process.48

Dolphins were long familiar to sailors of the Mediterranean, and some lore surrounded them (including classical myths, such as the tale of Arion riding a dolphin), which remained current in bestiaries at the end of the sixteenth century. According to Elizabethan zoologist Edward Topsell (ca. 1572–1625):

The swiftest of all other living creatures whatsoever, and not of sea-fish only is the Dolphin; quicker than the flying foule, swifter than the arrow shot out of a bow. . . . This is to be noted in them, that for the most part they sort themselves by couples like man & wife. . . . Of a man he is nothing afraid, neither avoideth from him as a stranger; but of himself, and fetched a thousand friskes and gambols before them. Hee will swim along by the marriners . . . and alwaies out-goeth them.49

Mermaids also appear in Holbein’s oceans, just above the equator to the east of Asia. They, too, emerge from myths but are credited as extant in contemporaneous accounts, such as Columbus’s report. Topsell notes:

And as for the Meremaids called Nereides, it is no fabulous tale that goeth of them; for looke how painters draw them. . . . For such a Meremaid was seene and beheld plainely upon the same coast neere to the shore . . . and the inhabitants dwelling neer, heard it a farre off when it was dying.50

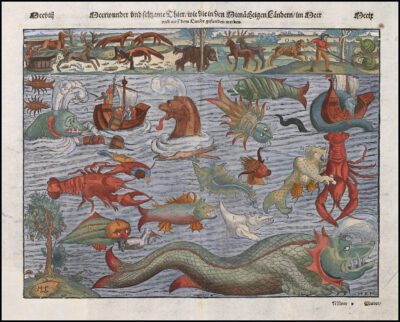

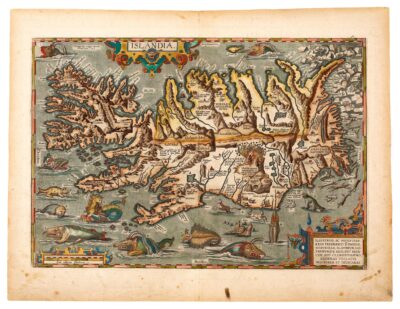

Finally, Holbein placed a monstrous fish on the map in the north Atlantic, not expressly identifiable as a whale but akin to other reported giant oceanic menaces. These monsters were recorded visually—with a key to their identities—by Olanus Magnus on his map of the northern oceans around Iceland (1539).51 That same image was later adapted for Münster’s Cosmographia (fig. 11) and adapted again by Abraham Ortelius in the first atlas, Theatrum orbis terrarum, published in Antwerp after 1570, as a more geographically oriented map of the island of Iceland (fig. 12).52

While Holbein also included a sailing vessel in the south Atlantic between South America and Africa, ironically it is not the kind of three-masted, oceangoing ship, such as a carrack or galleon, like those piloted by Columbus and other sailors of the period.53 Instead, it is a single-masted ship, a caravel, more appropriate for coastal trading and fishing, though with a high forecastle and a furled, square sail for open-water sailing. In short, this ship is nearly as fanciful within its oceanic context as the sea creatures themselves, revealing that Holbein again relied on another, unknown visual source.

In a unique element of Holbein’s design, placed at both the top and bottom of the globe, two angels operate cranks that suggest the earth’s rotation. Although two observers, including Meurer, have read these Holbein angels as anticipating Copernicus’s later theory of the rotation of the earth around the sun, published in 1543 as De revolutionibus orbium celestium, Münster himself continued to advocate for a geocentric view of the cosmos in his explanatory text: “The learned consensus is that the earth’s body has a spherical form and that the center of the world forms the center of the entire world machine.”54 Within Münster’s 1536 publication Organum Uranicum, a celestial woodcut, still geocentric, also shows two pairs of angels above and below the solar system and zodiacal spheres; they, too, turn cranks, acting as “angel-motors” of the cosmos.55

Prevailing cosmology from ancient astronomy—the model originated by Ptolemy himself—held that the motions of the celestial spheres around the earth were motivated by the primum mobile, by the first mover, essentially God himself, a divine force that might be personified through such angelic attendants.56 Münster adopts that inherited model of the universe, stemming from Ptolemy’s Almagest (second century CE), which meant placing the earth, immobile, at the center of the cosmos and thus unable to rotate around its own axis. However, some medieval debates continued about its possible rotation (just as some vestigial resistance to Copernicus’s theory remained across the later sixteenth century on behalf of an unmoving earth).57 Thus, Holbein’s earth, while seemingly represented as moving in rotation, is actually operating under a divine plan, with angelic agents manipulating the celestial spheres above.

Remarkably, a nearly contemporaneous tapestry series also depicts The Spheres—celestial, armillary, and terrestrial.58 Designed by Netherlandish artist Bernard van Orley (ca. 1499–1541) and woven in Brussels by Georg Wezeler (act. 1548) during the 1520s, these works were commissioned by Portuguese King João III to celebrate the remarkable voyages of his compatriots, first sponsored by Prince Henry the Navigator in the mid-fifteenth century. Each of the three familiar spheres is borne by powerful mythic figures: Hercules for the celestial sphere; Atlas for the armillary sphere (fig. 13), still based on the geocentric model;59 and Jupiter and Juno presiding beside an earthly globe, emphasizing Portuguese imperial expansion into the Indian Ocean through its view of both Africa and Asia (fig. 14). That globe remains centered on a vertical axis between sun and moon, surrounded by the traditional winds. The two Olympian rulers stand on supporting winged figures, respectively male and female, who could be read as angels. In the case of Atlas, the upper corners of the composition feature Mercury with his caduceus and Urania, muse of astronomy, bearing another armillary sphere on a pole. Together, these three more conventional tapestry spheres suggest how distinctive and innovative Holbein made his angelic pair on the 1532 map.

Holbein also collaborated with Sebastian Münster for additional woodcut designs. He illustrated zodiacal signs for Münster’s publication on creating sundials, Horologiagraphia (Basel: Heinrich Petri, 1533), and also for a do-it-yourself manual for constructing a sundial (1551), produced by the same publisher, Münster’s stepson.60 Their collaboration flourished briefly because Holbein combined his ability for visual precision with his collaborative experience in the production of woodcuts, made with a local cutter such as Veit Specklin (active ca. 1525–1550) (who used his monogram VS on blocks) and with Basel publishers, especially Petri.61

MÜNSTER’S GEOGRAPHY

Ptolemaic World Maps as Sources

For the shape of the world and its component continents, Münster clearly displays his knowledge of Ptolemy’s projections and their display in publications of Ptolemy’s maps. Beyond appealing to a general antiquarian interest within the Renaissance revival of ancient knowledge, Ptolemy’s treatise, Geographia, also aroused excitement because it provided methods to project the round globe onto a two-dimensional surface by using multiple coordinates to locate specific places. These coordinates essentially provided both latitude and longitude for any site. Ptolemy already had devised alternative grid systems for showing oceans and land masses.62 In one kind of Ptolemaic map projection, meridians of longitude, equidistant at the equator, are shown as curving and narrowing upward toward an implied convergence at the pole. Parallel lines define latitude in Münster’s map, but there they are horizontal and equidistant, so the resulting shape of the world becomes a curving oval (more squashed in some versions; figure 15 is from the 1482 German publication of Ptolemy from Ulm). This form of global representation, actually converging at both poles, was laid out in 1508 by Francesco Rosselli of Florence, who incorporated information about the western hemisphere from Columbus’s fourth and final crossing (1502) and that of John Cabot (1497).63 Thus, in terms of representation, Münster’s 1532 world map, through Holbein’s design, sensitively incorporates up-to-date cartographic information.

The curving segments of Münster’s map design also simulate in two-dimensions the newest earth form: the globe (Erdapfel), first fashioned in Nuremberg in 1492–1494 by Martin Behaim (1459–1507; fig. 16). Waldseemüller, in addition to his world maps, also produced printed woodcut gores (Minneapolis, James Ford Bell Library) that could be pasted onto a sphere to produce a globe. He was followed in 1515 by Johann Schöner, who published an accompanying manual in 1517, Luculentissima quaedam terrae totius descriptio (A very clear description of the whole Earth).64

In visual terms, Sebastian Münster also incorporated new cartographic insights into his 1532 world map. By this time, Portuguese voyages had already defined the basic contours of Africa, allowing a more accurate rendition of that continent in relation to the equator as well as the—newly labeled—Cape of Good Hope below the Tropic of Capricorn. On the 1532 map, what Münster calls “America” or “Terra Nova” is actually modern South America, whose north coast and projecting region of Brazil (“Prasil”) had been better explored by both Spanish and Portuguese ships than any part of North America. The lone exception, the Caribbean, contains labels for established Spanish colonial islands, Hispaniola and “Cuba,” whose name is transferred here to the entire East Coast of the present-day United States. Here Münster is responding to discoveries by Columbus in Venezuela for Spain and by Pedro Alvares Cabral for Portugal (in 1500), as well as by Amerigo Vespucci. While Münster shows the isthmus of Panama, discovered in 1513 by Balboa, the rest of North America still remains closely tied to Waldseemüller’s rendering, a narrow terra incognita. Like Columbus’s imagined “Cipangu” for Japan, Münster designates that island as “Zipangri” and places it in the north and near the west coast of the Americas, instead of in the eastern hemisphere beside the kingdom of China, “Cathay,” on the opposite side of his map.

As noted above, early in the sixteenth century, the newly discovered western hemisphere was already acquiring the name “America.” Adapted from the name of Amerigo Vespucci, because of his famously circulated reports, it was first designated at the left margin of Waldseemüller’s massive, multi-sheet 1507 world map (fig. 17). Waldseemüller also included a portrait tribute to that famous Florentine explorer beside his eponymous hemisphere (see fig. 17a).65

After collaborating with Holbein, Münster issued another map for his Latin edition of Ptolemy with updated maps. There he adopted the name America along with Brazil on his Novae insulae (Map of the New Islands; fig. 18).66 That map shows the flags of both Spain and Portugal for the regions they respectively claimed; additionally, it retains the same cannibals and sailing ship adapted from Holbein’s 1532 designs. By that point, details of the region—called, in German, Die Nüw Welt (The New World)—had been much nuanced. Münster’s 1540 map shows Cuba in proper scale at its Caribbean location, alongside a much larger North America and Central America. Japan is still shown as an island (Zipangu) just beyond the west coast of the Americas. This later map, with its new, inserted continent, formed part of Münster’s Geographia universalis (1540), his updated world geography, with the original Latin text by Ptolemy.67 But by then, Holbein was already in London, so his fascinating figural scenes are absent from all later maps by Münster.

Elements of Münster’s 1532 map replicate details from Ptolemy’s ancient understanding of the wider world. For example, Münster retains directional delineations by distributing the classical names of winds on banners in cursive Latin, placed around the margins of his oval globe. Regions from ancient maps reappear in their familiar forms, as does the established visual vocabulary for seas, mountains, and rivers, especially the Nile. However, sites far more distant from Mediterranean Europe, unexplored areas in Ptolemy’s delineation, reappear in a similar form, especially at the global margins. In particular, the southernmost tip of Asia curves downward and inward, a residue of Ptolemy’s vision of an enclosing coast, containing the entire Indian Ocean in a basin that mirrors the Mediterranean (a concept discredited by Portuguese voyagers after Vasco da Gama reached India in 1498). Also following Ptolemy, Münster cuts off the subcontinent of India above an overlarge island, roughly equivalent to Ceylon/Sri Lanka, but called by its medieval name, Taprobana. Equally distant and still unfamiliar, northern Europe around Scandinavia curves irregularly into a generalized C-shape as a peninsular projection from “Muscovia.”

In terms of knowledge written on the 1532 map, a Latin text about India stresses the origin of the region’s name from the Indus River and itemizes its exotic fauna (parrots and rhinos) and spices (cinnamon, pepper, and aromatic calamaus root, extracted for its oil), plus its gemstones. The text also mentions dark-skinned people “from birth,” who wear minimal clothing. About Scythia, Münster’s text on the 1532 map emphasizes a traditional division of the region into two parts, separated by mountains, and locates its position adjacent to Tartary, home of Mongols.68

Vestiges of classical sources, such as Pliny, remain in Münster’s Cosmographia to address its learned, Latin-literate audience and further reveal the text’s complex mixture. Together with contemporary travelers’ tales, the book attempts to encompass the entire world, in terms of both geography and ethnography. Margaret Hodgen aptly characterizes its purpose as “planned not only to inform but to entertain, thus perpetuating one of the chief characteristics of the medieval encyclopedia.”69 To underscore his reliance on venerated or reliable sources, Münster appends a bibliography, Catalogus, doctorum, virorum quorum scriptis & Ope[re] sumus usi & aduiti in hoc opera (Catalogue of the doctors and men whose writings and works we have used and assisted in this work). Among these he includes recent travelers by their Latin names: Vartomannus, Olaus, Vespucius, Columbus. Margaret Hodgen also underscores Münster’s debt to Boemus.70 As noted above, the first edition of Münster’s Cosmographia appeared in German in Basel in 1544, followed by its Latin version in 1550. Numerous translations and editions remained in print until the mid-seventeenth century. The initial Münster title page shows the hierarchy of rulers in the Holy Roman Empire and Christian realms above, with leaders of major powers in niches below, while a bottom scene with an expansive landscape contains distant peoples, spice plants, and animals, represented by an elephant (fig. 19). As Matthew McLean observes: “This panel informs the reader that the Cosmographiae Universalis describes in six books, all the habitable parts of the world, their inheritances and gains, the topographical likenesses of regions, the character of lands and how they differ in their contents, both living and inanimate.”71 In his English translation, Münster himself declares his purpose: “I have written here of the peoples and nations of the whole world, with their attainments, laws, costoms [sic], manners, religions, ceremonies, kingdoms, principalities, trades, antiquities, lands, animals, mountains, rivers, seas, lakes, and other features.”72

That larger universal ambition was signaled in Münster’s 1532 world map, produced in Basel with expert artistic contributions by Hans Holbein. Together, they produced a map that complemented the volume of traveler’s tales of which it was a part. Bearing its own heading, Typus cosmographicus universalis, the 1532 map collaboration between Holbein and Münster declares sweeping ambition and inclusiveness for its time, not only among maps that show the entire world (according to the best knowledge at that time), but also among maps that depict human regional behaviors on the three other known continents besides Europe, home of the intended audience. This map also gestures toward nature (with sea creatures, animals, and spice trees) and even toward the wider cosmos, through its reference to angelic realms. Accompanied by Münster’s Latin texts, the map describes distant India and Scythia. Significantly, while part of a larger book publication rather than an independent work of Münster, this joint project would culminate in Münster’s own lifelong project: his 1550 Cosmographia.73