Jan Gossart is well-known for introducing the mythological nude into Netherlandish painting. Equally significant was his discovery of the body in motion, in contact with others. In stressing this contingent aspect of the human body, Gossart appealed to an unprecedented degree to the viewer’s empathic response. Such pictorial empathy, occasionally documented in the early modern period, has been a mainstay of art historical writing and aesthetics since the later nineteenth century. More recently, it has been endorsed by newer neurological research. By reviewing these critical approaches, I hope to demonstrate a line of embodied response that spans the centuries from Gossart’s career to the present that may help us come to terms with some idiosyncratic aspects of his images.

Jan Gossart (ca. 1472–1532) has long borne the fame of being among the first artists in the Netherlands to paint mythological nudes–poesie–as Ludovico Guicciardini and Giorgio Vasari asserted within a half-century of his lifetime. Karel van Mander would praise Gossart in slightly more technical terms for finding the “right method of composing and fashioning history paintings full of nude figures and other sorts of Poeterijen” which the artist had imported from Italy.1 Certainly the portrayal of the human body, especially the naked body, was central to Gossart’s art, as it had not been to his earlier countrymen.2

Gossart and the Nude

Yet Gossart’s introduction of the independent mythological nude into Netherlandish painting was not his sole achievement. Equally significant was his discovery of the body in motion, the body in contact, the body contingent on the motives and actions of others. It is somewhat surprising to realize that Gossart’s Netherlandish predecessors acquitted themselves by presenting the human figure as an independent and unattached ideal form. Gossart’s protagonists, in their unexpected poses and collocations, remind us that the human body as cultural construct was then undergoing significant revision.

In stressing this contingent aspect of the human body, Gossart profoundly altered the relationship between viewer and picture. His novel, active, and engaged portrayal of the human form, his unusual and unprecedented poses and gestures, encouraged a newfound awareness in viewers of the potential of their own body and, intuitively, of their own complicity in the actions portrayed. We might think that the artist appeals, to an unprecedented degree, to the empathy of the observer, who may instinctually trace the moves and maneuvers of the figures depicted. Early modern sources offer some evidence for this type of embodied response, and recent neuroscientific studies seem to endorse such physical identification with objects or actions viewed. This stress on the observer’s empathic response has not featured in recent criticism of Gossart’s works, but it has been very much an aspect of art historical writing since the later nineteenth century. I am thinking of German theories of aesthetic empathy that engaged closely with contemporary research in psychology. And I have in mind the more recent discussions of kinesthetic empathy or identification.3 By reviewing various critical writings, I wish to emphasize a line of response rooted in the body that spans the centuries from Gossart’s career to the present and may help us come to terms with some idiosyncratic aspects of his images.

Gossart’s most provocative painting is perhaps his small panel Hercules and Deianira, which portrays the two mythological figures locking legs in what seems at first a highly peculiar pose (fig. 1). Certainly the court milieu around Philip of Burgundy fostered the depiction of such humanist subjects with their inescapable erotic charge. Art historians have interpreted the idiosyncratic, enveloping figural arrangement as a pictorial sign of their physical intimacy, as a sort of emblem of copulation.4 But this explanation says little about the visual or psychological effects promoted by their contortions. Such a view tends to reduce Gossart’s pictures to texts, to a series of disembodied signs. Gossart’s images, however, are profoundly physical and implicate the viewer in ways that are felt as much as thought. Significantly, his painted nudes appear decidedly sculptural. Gossart mastered the meticulous Netherlandish facture of the fifteenth century, which presented flesh as a smooth and enamel-like surface. To this he added dramatic modeling that cast body parts as fully three-dimensional forms, set out in stark relief–a manner of presentation that seems to stimulate a pronounced tactile response. Gossart has, in fact, been viewed as being in competition with contemporary sculpture. Maryan Ainsworth suggested that the painter entered into a sort of private paragone with Conrat Meit (ca. 1480–ca. 1550), the leading sculptor at the Netherlandish courts and a close acquaintance of the painter.5 In his Neptune and Amphitrite and in several of his pictures of the Virgin and Child, Gossart likened flesh to the white purity of polished marble.

The daringly naked Hercules and Deianira sit together on an antique bench with Hercules’ arm around the shoulders of his companion. The strange positioning of the legs conveys visually and intuitively the physical, erotic nature of their involvement–even of the complex and difficult history of their entanglement. Hercules holds in his other hand an armored club, symbol of his power and virility, and Deianira rests her far hand on a cloak, a gift to her lover that will bring about his death. But the picture is not chiefly about this sad narrative, which is indicated only as a footnote.6 Gossart’s small panel is principally about the ineluctable appeal of the flesh, the nature of sexual longing– conveyed so powerfully by the strange imbrication of these nude figures.

Gossart’s treatment of the human form was remarkably varied in terms both of pose and scale. Pictures like his Neptune and Amphitrite with its nearly life-size nudes must have astounded the aristocratic audience at the Palace of Souburg in Zeeland, where Philip of Burgundy held his court. Gossart’s journey to Italy is usually adduced as the primary source of inspiration for this aspect of his art.7 The work of the Nuremberger Albrecht Dürer, however, was an equally important inspiration for the Fleming and points to the broad international scope of the arts in the Netherlands during the early sixteenth century.8 It might be better to see Gossart as partaking of a current and ongoing pan-European discourse on the notion of the body. In the context of the Low Countries, however, his emphasis on physical engagement, on aggressive action and interaction, was unprecedented.

Gossart’s approach is also manifest in his depiction of Hermaphroditus and Salmacis (fig. 2), another story taken from Ovid, and like Hercules and Deianira, represented on a small scale.9 The nymph Salmacis, desperately in love with the youth Hermaphroditus, spies the object of her ardor bathing in a pool. Her embrace of Hermaphroditus and her plea to the gods that they be eternally joined results in their unification as a single bisexual being–the hermaphrodite. Gossart shows this divine solution in the background at the left; the two characters emerge from a single pair of legs. The greater part of the painting, however, is occupied by the two naked actors grappling in the foreground. Salmacis violently takes hold of Hermaphroditus about the neck and arm, their legs interlocked. The two nudes enact the effects of desire for the ideal forms they represent. The novelty of this bodily entanglement was in itself seductive.10 And again we might wonder whether the struggling figures would have excited the imagined sensations of embrace and resistance in the mind of the observer.

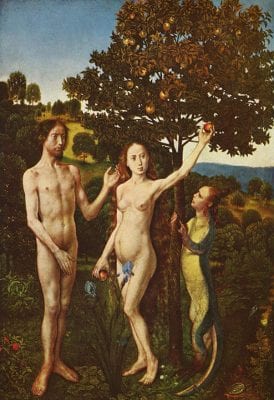

Gossart’s most physically imposing images are perhaps those depicting Adam and Eve.11 Of course, images of the Fall were uniquely charged with concerns about sexual attraction and its moral consequences. This theme had a venerable tradition in both panel painting and manuscript, memorably including Jan van Eyck’s two large panels of Adam and Eve in the Ghent Altarpiece.

In Gossart’s more dramatic art, the notion of original sin is actively inscribed in the posing and manipulation of the bodies; it is read as a consequence of their physical interactions. The most disturbing of Gossart’s visualizations of the Fall may be the pen and chalk drawing in Frankfurt, most probably a copy of a lost original (fig. 3).12 Adam has fallen to the ground in an apparent attempt to avoid Eve, but she hovers over him, permitting no escape. Adam’s body emerges dramatically from the middle ground, his right hand extending to the picture plane, where it rests at the lower left corner. His leg is slung across Eve’s thigh in intimate contact. In her hand she holds the apple, precisely at the center of the drawing, where Adam reluctantly touches it. The Frankfurt drawing is a pathetic image in which Adam desperately struggles to avoid the carnal temptation in which he is already implicated.

Only slightly less aggressive is the chalk drawing Adam and Eve in the Rhode Island School of Design (fig. 4),13 again, a copy of a lost original by Gossart. Eve, in the rear, leans forward toward a recoiling Adam, who seems to hesitate as he reaches for Eve’s body–her naked torso and bare breasts rest a few tantalizing inches from his touch. Eve raises her left arm high to grab the apple; with her right hand she reaches for Adam’s genitals. Studying the Rhode Island drawing, the viewer would register the torsion of the bodies, the crossed legs, the shifted weight of Eve as she bends toward Adam.

Gossart’s dramatic and nearly life-size painting of the Fall in Berlin shows his adaptation of these principals to a much grander scale (fig. 5).14 Although these monumental nude figures do not make contact with one another, they boldly stride out of the recesses of the picture and threaten to encroach on the space of the observer. Eve pursues Adam while extending to him the apple, while Adam turns abruptly away, signaling caution. The poses and gestures of pursuit and avoidance seem automatic, ingrained,15 and forcefully convey the psychological dimensions of the encounter. Eve is unusually aggressive; her posture in particular departs from the expected manner of portraying her. Adam’s ungainly form likewise deviates from respectable models. Pierre Bourdieu, in particular, has discussed the social values that accrue to learned bodily behavior–the manner in which gender identity and notions of propriety, for example, are signaled by the way the body interacts with its environment.16 Gossart’s design impels the viewer to confront the two figures and their action with unusual immediacy.

There are two especially noteworthy aspects to all three representations of the Fall. First, the figures dramatically protrude from the fictive space of the picture and threaten the traditional distinction between the confines of the image and the area of the observer. Second, Gossart’s bodies are given complex, convoluted poses and closely interact with each other. To present-day viewers, bred on the art of later centuries, these figures can seem contrived, mannered, and willfully contorted. But to the artist’s original audience, this way of presenting the human body was essentially novel.

Indeed, these techniques were unprecedented in Netherlandish painting. The small panel of the Fall by Hugo van der Goes (ca. 1440–1482) in Vienna typifies the approach to this subject of the previous century (fig. 6).17 Hugo’s Adam and Eve stand stationary and erect. They present themselves frontally and address each other only obliquely, while preserving their individual space. There is no contact, no movement forward, and their bodies are posed in fairly uneventful ways.

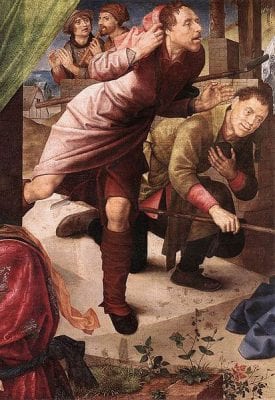

During the century of Jan van Eyck (ca. 1390–1441), most representations of the human figure–especially nudes–remained within discrete spatial shells, occupying tubelike volumes but rarely interacting physically with each other. This image of the body may be related to notions of courtly etiquette, of a sense of proprietorship over social space, and it is therefore not surprising to find prime examples of this attitude in earlier pictures such as the panels by Dirck Bouts (ca. 1415–1475) representing the Justice of Emperor Otto of about 1475 (fig. 7). The courtiers around the executed count stand tall without any contact or physical interaction. They occupy independent modules that combine to form the joint space of the picture. Manners books of the time supported such presentation. Erasmus’s De civiltate morum puerilium directed the young to stand erect with the shoulders evenly balanced and to avoid sitting with legs crossed.18

Gossart was not inattentive to the work of earlier Netherlandish artists, although their lessons were limited regarding the portrayal of the body. An exception, is Hugo van der Goes–not so much his depiction of the Fall as his late works like the Adoration of the Shepherds in Berlin (fig. 8). Gossart might have been particularly taken by the two shepherds rushing in from the left (fig. 9). The nearer one inclines forward and seems barely to retain his balance; his left leg is firmly planted but his right one is raised at an angle. The rear shepherd kneels and bends abruptly, one hand up at his breast and the other down holding his crook level. In their unconventional and ungainly poses, these figures demonstrate a profound appreciation for the affective power of the body; their physical instability conveying the emotional instability of joyous adoration.

Gossart and Empathy

We might now return to Gossart’s Hercules and Deianeira as a paradigm of the artist’s approach to the body. The sheer novelty of the pose clearly prompted a new kind of response. The viewer might well try to imagine what such an embrace would feel like; the complex assemblage of the two bodies, the tactile play of interwoven legs, tempts the viewer to resolve the visual puzzle by projecting him- or herself into such a maneuver. Hans Belting has made a similar point: “We anyway closely relate images to our own life and expect them to interact with our bodies, with which we perceive, imagine, and dream them.” Belting states further, “Bodies perform images (of themselves or even against themselves) as much as they perceive outside images. In this double sense, they are living media that transcend the capacities of their prosthetic media . . . When absent bodies become visible in images, they use a vicarious visibility.”19

That such embodied empathy has a historical foundation is suggested by a number of early modern documents. Particularly suggestive is Anton Francesco Doni’s discussion of the Laocoön in his treatise on the relative merits of sculpture and painting from 1549. Doni relates that viewers were so moved by the pathetic representation of the doomed father and his sons that they felt compelled to writhe, emulating the poses of the carved figures.20

An actual encounter with an art work along these lines is reported in Paul Fréart de Chantelou’s journal, which records the visit to France in 1665 of Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680). Chantelou describes the sculptor’s very physical response to a painting by Veronese as he criticized the unnatural pose of one of its figures: “‘The upper part is turned one way and the lower part another, and this contortion cannot be made by nature.’ Saying this [Bernini] tried to assume the same pose but was unable to hold it.”21

Neuroscientific studies appear to offer biological evidence for this sort of response. For our purposes, this research is especially important because it shows continuity in a centuries-long discussion on the power and agency of images, in the discourse on viewer response to representations of the body. Of course, sexuality and emotion are intimately linked to these reactions, and both have been explored in relation to early modern images.23 To keep this discussion bounded, however, I will restrict my analysis to perception of touch and bodily arrangement.

As the neuroperceptual and neuroaesthetic research of Semir Zeki, Vittorio Gallese, Antonio Damasio, David Freedberg, and many others has shown, subjects observing the depiction of actions display neural responses similar to those of the subjects executing these acts.24 Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has demonstrated that in both cases the firing of what are called mirror neurons occurs in the same regions of the brain. The perception of the sense of touch, so central to Gossart’s painting, seems to obey this principal. Christian Keysers et al. reported that neural activity is found in the same area (the secondary somatosensory cortex) whether a participant has been touched directly or has rather observed someone being touched by an object.25 Indeed, the response to representations of touch has been studied in some detail,26 and it has been shown that the pattern of neural response is quite nuanced, registering differences in in the shapes of the objects touched.27

Much of the neural-sensory research has explored the brain’s response to perceptions of movement–to touch as the result of an action–and is therefore somewhat removed from the experience of pictures.28 One area of investigation that somewhat circumvents this focus is research on response to the mere expectation of movement and touch. The results demonstrated a remarkable similarity in terms of neural activity between the reaction to sensory stimulation and that of the state of anticipation.29 We might wonder whether paintings such as Gossart’s Hercules and Deianira elicited the expectation of touch after evoking the memory of related bodily contact.

But there are also studies of neural activity that employ still images. A. C Pierno et al. used still photographs of a hand grasping an object, a hand pointing to an object, and a hand at rest by an object. Not only did the three photographs generate consistently different neural responses, but the representation of the grasp occasioned considerably more overall activity in certain regions of the brain.30 Here, too, the authors concluded: “observation of hand actions would automatically induce the observer to re-enact the observed actions.”31 David Freedberg and Vittorio Gallese relate these studies directly to the viewing of art in comparable terms: “It is not surprising that felt physical responses to works of art are so often located in the part of the body that is shown to be engaged in purposive physical actions and that one might feel that one is copying the gestures and movements of the image one sees.”32

We might seek in these findings a partial explanation for the powerful effect of the Hercules and Deianira on the viewer through excitation of neurons governing the sense of touch and muscular activity. There are, naturally, problems in applying these results beyond the narrow parameters of the specific experiments. Studies conducted with the use of photographs presume familiarity with the medium in an image-saturated society. The distinct early modern viewing context—the relative paucity of images—may have augmented or reduced the effect of Gossart’s paintings. Furthermore, the experiments make no allowance for differing representational techniques among artists. Would viewers respond more emphatically to Gossart’s highly sculptural presentations than to Quentin Massys’s softer, sfumato-laden figures?

Larger conclusions about human psychology and perception, about human nature—whether offered by neuroscientists, cultural historians, or aestheticians—are inevitably indebted to earlier notions of the mind/body relationship.33 The neuroscientists Giacomo Rizzolatti and Gallese, for instance, acknowledged their longstanding interest in the phenomenology of Maurice Merleau-Ponty.34 One of the major contributions of John Onians’s consideration of neuroarthistory is his placement of current neurological research at the end of a long tradition of thinking about the biological imperatives in the creation and reception of art.35 A limitation of much neuroaesthetics is its lack of historicity, its implicit assumption that brain functioning is a constant unaffected by the passage of time or by differences in cultures.36 It is obviously not possible to perform functional magnetic resonance imaging on people from previous centuries. Another question has to do with brain plasticity, whether habitual exposure to new art works can, in effect, train the brain to respond differently under certain conditions, which might reveal altered neural networks.

Herman Roodenburg and Monique Scheer observed, for instance, that neural response differs according to the particularities of individual experience, as a study by B. Calvo-Merino et al. seems to demonstrate. Three groups of subjects were all shown videos of classical ballet and Afro-Brazilian capoeira dance. One group was composed of experienced ballet dancers, the second of subjects trained in capoeira, and the third of people with no dance experience. Significantly greater brain activity occurred when subjects viewed the performance of a dance style they had previously practiced. The results clearly showed the importance of acquired motor skills and the “cultural tuning” of neurons.37

This neurological research does not stand alone, however. It accords with the reports of artists, philosophers, and natural scientists since the early modern period, strongly suggesting empathy as a significant and longstanding mode of response to the represented body and to Gossart’s nudes in particular.

Indeed, the idea of investing oneself physically and psychologically in an image, of merging subjective feeling with an object of aesthetic vision, brings to mind the notion of empathy or Einfühlung, so prominent in art historical writing of the later nineteenth century. German authors such as Robert Vischer and Theodor Lipps argued for the primacy of this sort of psychological and emotional identification with represented forms.38 Different authors dealt with the concept of empathy in different ways. More than Vischer or Lipps, Johannes Volkelt explicitly linked visual apperception to the physiological dictates of the body, to bodily participation in the visual experience of spatial forms, as Helen Bridge has noted.39

This was not an exclusively German discourse. The French philosopher Henri Bergson developed his own notions of empathy and vicarious bodily involvement in art in his Time and Free Will of 1889, in which he explicitly relates the reenactment of body movement to the comprehension of underlying emotion.40 Writers like Bergson provided an early foundation for the concept of kinesthetic empathy.41 And while this idea has usually been invoked to help understand responses to dance and other forms of orchestrated movement, it has also been applied to the perception of stationary bodies and objects.42 As Amelia Jones has written, we give meaning to the impressions of an instant by referring to embodied memories of previous experiences.43

An empathic response to Gossart’s images, thus, appears to be supported by a wide variety of sources—from early modern reports and images, through aesthetic and philosophical writings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, to neuroscientific studies in the last few years. We can posit that such embodied viewing represented a significant mode of access to his pictures of mythological subjects and of Adam and Eve.

Gossart’s innovative approach to the body, however, found a rather uneven reception. Although certain painters like Bernard van Orley (ca. 1488/92–1541 or 42), Pieter Coecke (1502–1550), and Joos van Cleve (d. 1540 or 41) profited from his example, the numerous and prolific artists known as the Antwerp Mannerists adopted a rather different approach, eschewing spatially complex poses and suggestively tactile surfaces for an emphasis on surface organization, on striking contours and flamboyant costumes. The rhythm of the profiles that defined these flattened forms was a significant aspect of the “artfulness” of these works.44

Gossart, though, created more than a new bodily canon. His paintings powerfully compelled the viewer’s participation and heightened the sense of ethical complicity in the actions represented. By the mid-sixteenth century audiences had become saturated with Gossart’s innovations. The twisting torsos and angled limbs had had their day, and younger painters such as Frans Floris (ca. 1519–1570), Willem Key (ca. 1515–1568), Jan Massys (ca. 1509–1575), and Lambert Lombard (1506–1566) settled on a new understanding of the human form.45 Gossart’s inventions of interrelated bodies for mythological pictures and images of the Fall, however, helped create not only a new subject in Netherlandish art but a new manner of regarding it.