Gerard de Lairesse (1640–1711) painted little more than a handful of portraits. A

relatively high proportion of these, however, especially in the period between 1668

and 1672, are portraits historiés, in which the sitter or sitters are in the guise of

historical, mythical, or allegorical subjects. In 2001, Glasgow Museums acquired

Lairesse’s Allegory of the Senses, signed and dated 1668. This article explores and

explains the complex iconography and unusually complete provenance of the

Glasgow painting and identifies the sitters as the three children of Pieter van Rijn

(1633–1712), Amsterdam merchant and marine auctioneer, and Elisabeth Bessels

(1634–1708).

Lairesse and Portraiture

Despite his profound interest and ability in depicting the human figure and facial expressions, Gerard de Lairesse (1640–1711) painted little more than a handful of portraits. A relatively high proportion of these, however, especially in the period between 1668 and 1672, are portraits historiés, in which the sitter or sitters are in the guise of historical, mythical or allegorical subjects. The most direct is the small but striking Portrait of a Woman as Minerva of about 1670 in Sibiu, Romania; the sitter is unknown (fig. 1).1 Of greater interest here is the square-format Apollo and Aurora, dated 1671, now in New York (fig. 2).2 Rejecting Alain Roy’s suggestion that the figures represent the Apotheosis of William III,3 Walter Liedtke found persuasive evidence that the sitters are two of the children of the wealthy Amsterdam burgomaster Nicolas Pancras, namely his young son, Gerbrand (1658–1716), and daughter Maria (1662–1740).4 He proposed that Nicolas commissioned the painting, described in 1716 as a “Schoorsteen-stuck” or “chimneypiece,” as part of the decoration for his new house at no. 539 Herengracht, along with a set of eight grisaille canvases on the theme of the Triumph of Aemilius Paullus Macedonius (ca. 1670), now in Liège (Musée de l’Art Wallon).

Lairesse evidently disdained portraiture as a genre, later writing of it that he “wondered how any man can prefer slavery to liberty.”5 His solution lay in avoiding literal representations at all costs and instead “mixing the fashion with what is painter-like”—or, in other words, finding the necessary beauty, grace, and decorum by adopting the antique rather than the modern mode so as to make his portraits as much like history paintings as possible.6 One key advantage of this approach was that by providing his figures with the loose, classical (or quasi-classical) dress of the antique mode, appropriate for historical subjects, Lairesse made their costumes timeless and avoided the awkward consequence of them appearing dated owing to the constant changes of modern fashion.7 An extension of this use of clothing to create an antique manner was the introduction of appropriate props that alluded to the sitter. These could either be added to the background, or, as in a portrait historié, the whole subject might be given a historical, mythological, or allegorical setting, thereby elevating the status of the sitter through association with classical ideals.8

For Lairesse, then, one of the potential drawbacks of a portrait historié—that it could so easily be read as a straight history painting by anyone unfamiliar with the sitter—might if anything have been regarded as an advantage. He clearly preferred the high genre of history over the low genre of portraiture. But, 350 years later, that can present us with a challenge in determining whether a painting is a portrait historié or simply a pure allegory. Sometimes, as with the Pancras children, we may have an undisputed portrait of a sitter with which to confirm an identification.9 In other instances, family tradition, backed up by extensive archival research, may establish a convincing case.

In 2001, Glasgow Museums acquired Gerard de Lairesse’s Allegory of the Senses, signed and dated 1668 (fig. 3).10 It is one of only three paintings by the artist in a UK public collection.11 The intention of this article is to explore and explain the iconography and provenance of the Glasgow painting more accurately and thoroughly than has been attempted hitherto and thereby better place it within Lairesse’s oeuvre.

Lairesse and the Tradition of the Five Senses

In the Glasgow Allegory, the Five Senses are represented primarily by the attributes held or associated with each of the five foreground figures. As Lairesse himself later wrote in his Groot Schilderboek (The Great Book on Painting): “An allegory exists completely of obscure matters, which common people cannot understand without an additional explanation. The figures do not show their true selves, taking on a different semblance. Therefore it is essential to depict these figures without any ambiguity, lest they are misunderstood and censured by wise men.”12

Touch is represented by the woman in golden brown on the left, whose right hand is being pecked by a green parrot. Taste is symbolized by the piece of fruit, perhaps a peach, held by the other woman, in dark green. Hearing is alluded to by the triangle sounded by the boy on the left. Smell is indicated by the spray of flowers held by the central girl. Sight appears in the shape of the elaborately framed convex mirror, which reflects the pointing hand of the small boy on the right. Secondary symbols of the Senses are provided by the fruit and nut-nibbling monkey (Taste), the prominent vase of flowers (Smell), musical instruments and myrtle (Hearing—myrtle oil helps clear the ears), tiny snail (Touch—since snails retract when touched), and, perhaps, the partially uncovered classical reliefs of the stone altar, which may suggest Sight.

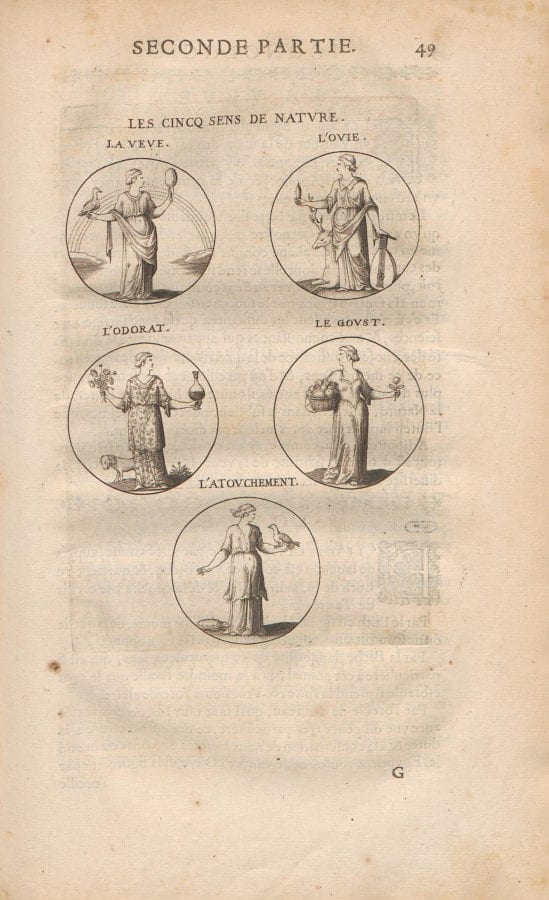

The symbolism ultimately derives from Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia. First published in Rome in 1593, with an illustrated edition appearing in 1603, Ripa’s hugely influential treatise underwent six more Italian editions by 1645. During his upbringing and training in Liège, Lairesse could have come across the first French editions of 1636 and 1644, but in fact we have his own testimony that “when my [eldest] brother returned from Italy with Cesare Ripa’s book [it had] that until then . . . been unknown to us,”13 suggesting it was probably a recent Italian edition or reprint that he saw at this time. This rekindling of what he called his “smouldering inclination” toward allegorical subjects must have been as late as 1664, just four years before the date of the Glasgow allegory. As Lairesse also wrote, “Without any doubt, Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia is a laudable, excellent and useful book for all artists whose work has its roots in the art of painting.”14

Lairesse has, however, adapted Ripa’s prescribed symbolism to effect a composition of the Five Senses that is less cluttered with large animals and perhaps more plausible than is suggested in Iconologia. Thus, instead of the clawing falcon and tortoise of Ripa’s Touch, Lairesse introduces a pecking parrot and a snail; Ripa’s secondary symbols of an ermine and a hedgehog are nowhere to be seen. Taste here holds a single fruit rather than a basketful, though there is a platter nearby. Similarly, Hearing has lost its stag (an animal celebrated for that particular sense), and a triangle replaces what would have been an unwieldy lute for the infant personification. Smell and Sight have attributes closer to those of their models, although again devoid of their animal companions of vulture and lynx, respectively. The net result is a lucid composition, the clear colors and forms set against a backdrop of sharp-edged classical architecture, all in accordance with the tenets of mid–seventeenth-century European classicism.

Artists, especially of the Netherlandish School, had treated the subject of the Five Senses long before Ripa published his Iconologia, which drew upon some of the same sources as those earlier artists. The portrayal of the senses in the visual arts began in the sixteenth century, initially limited to print series. The standard formula was introduced in the 1561 series by Cornelis Cort after designs by Frans Floris, in which Hearing is close to the personification depicted by Jacques de Bie in the 1643/44 French edition of Ripa (fig. 4).15 The much-copied Saenredam-Goltzius series of about 1595/96 is altogether more adventurous, with an overtly romantic, even sexual character, featuring entwined couples in contemporary costume and sometimes only the token inclusion of traditional symbolism.16

Also quite common in both the Northern and Southern Netherlands during the mid-seventeenth century were sets of five small paintings, each work representing one of the Senses. These were often aimed at a less sophisticated middle market, and the elegant iconography derived from classical sources was pushed aside in favor of altogether more rudimentary symbolism. A typically crude example is provided by the representation of Smell by the Haarlem artist Jan Miense Molenaer, featuring a toddler having his bottom wiped.17

Much rarer are depictions of the Five Senses within the expanse of a single painting. An interesting example closer in date to the Lairesse than the other works mentioned so far is Herman van Aldewereld’s painting of 1651, now in Schwerin (fig. 5).18 The composition, with its additive accumulation of details and cramped-up overlapping figures, is awkward compared to the elegance and clarity of the Lairesse, but, with the exception of the harp for Hearing, the attributes held by each figure are closely comparable. It is possible that Lairesse had first-hand familiarity with the painting by Van Aldewereld, an Amsterdam artist.

While an Allegory of the Five Senses is the ostensible subject of the Glasgow painting, there is a great deal more to unpack. The capuchin monkey, clasping a walnut to its mouth, is an attribute of Taste.19 But similar monkeys are also frequently found in the context of vanitas subjects, mocking the folly, avarice, and short-lived worldly pleasures of man.20 Given the transience of the Senses, there may be a secondary meaning here.

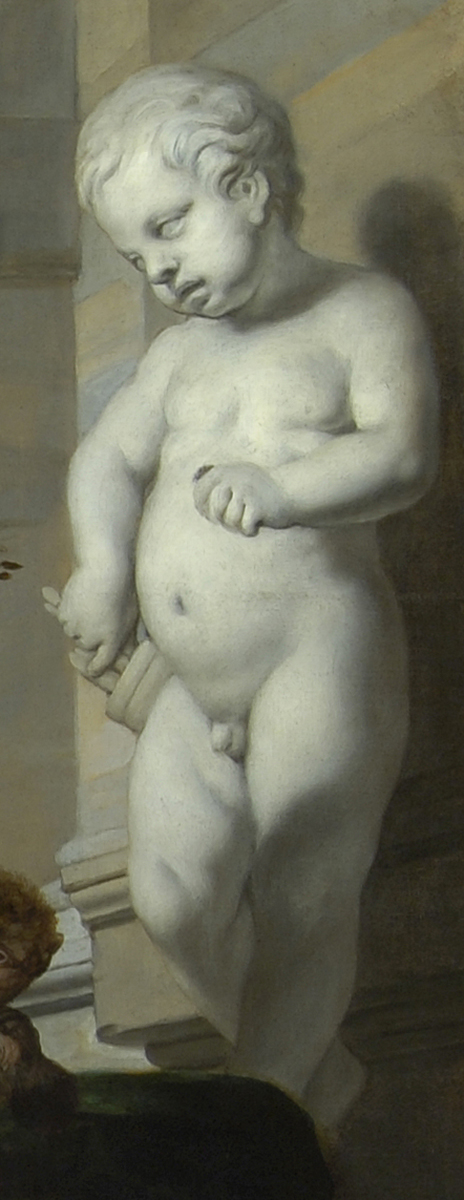

More intriguing is the prominent figure of Cupid (fig. 6), carved from immutable and flawless marble or stone and placed on what would seem to be a marble altar. He presides over the right-hand side of the whole composition. The sculpture is probably modeled on statuettes of putti made fashionable by the Flemish sculptor François Duquesnoy (1597–1643), especially his marble Cupid Carving His Bow of ca.1626 (now in Berlin), which was brought to Amsterdam in 1629 and was in the gardens of Princess Amalia van Solms’s palace in The Hague in the 1660s (fig. 7).21 Lairesse himself wrote, “François Duquesnoy’s children are excellent examples to be copied in paint. Nobody ever reached the same level of perfection.”22 He also wrote that “a painter who wants to elucidate his story with allegories, mostly makes use of some sculpture.”23 In his monograph, Alain Roy suggested that the three children—perhaps he meant the central girl—were offering a kind of homage to the god, and indeed the eldest child does seem to be stepping toward Cupid and presenting him with her bunch of roses.

The Painting’s Provenance

We are fortunate that an inscription on the back of the Glasgow canvas introduces a further level of interpretation in respect to the children. Written in white-chalk capital letters are the words: “THE THREE / CHILDREN ARE / VAN RYN.” The implication of this inscription, apparently modern but presumably following family tradition, is that in addition to being allegorical personifications of three of the Senses, the three foreground children are portraits.24 In what follows, I will examine whether this is indeed plausible and who these children may be, primarily through careful analysis of the painting’s provenance and archival research into the earliest owners.

Glasgow Museums acquired the painting in October 2001 from Richard d’Orville Pilkington Jackson (1921–2009). He had inherited it from his father, Charles, on the latter’s death in 1973. Charles d’Orville Pilkington Jackson (1887–1973) was a traditional figurative sculptor based in Edinburgh who enjoyed a long and successful career and is probably best known today for his Robert the Bruce monument at Bannockburn (1964).25 He had in turn inherited the Lairesse from his mother’s uncle, the minor marine and portrait artist Hely Augustus Smith (1862–1941), to whom it had passed from his father, the Reverend Hely Smith. This Reverend Smith had married one Harriet Morton, the daughter and heir of Joseph Morton, who himself had married Elizabeth d’Orville (?1782–1883). She was the last in the line of d’Orvilles through whom Richard Pilkington Jackson believed the Lairesse Allegory had traveled directly down the generations. He understood the first owner of the painting to have been a Jean d’Orville (1626–1694).26

Roy had traced the provenance back to Jacques-Philippe d’Orville (1696–1751) (fig. 8), and this, indeed, proved to be the furthest back in the d’Orville family that the painting could be documented.27 Jacques-Philippe, of French Huguenot descent, was one of the greatest scholars of his day in Europe.28 The son and brother of wealthy merchants, he traveled frequently and widely in the 1710s and 1720s, meeting and corresponding with leading contemporary scholars and collectors of antiquities, including Linnaeus and Montfaucon. In the 1730s, he was established as a famous “Professor of History, Eloquence and Greek” at the Athenaeum Illustre in Amsterdam before eventually retiring to his estate at Groenendaal, near Haarlem, where he died in 1751.29

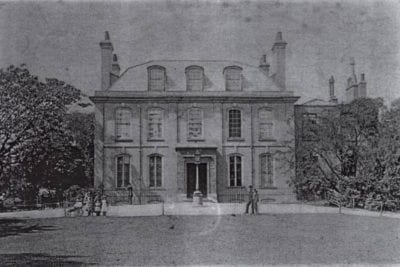

It was also known by Richard Pilkington Jackson that Jacques-Philippe’s son, Johannes (1734–1799), a merchant, came to England and established his family at Ravenscourt Park in Hammersmith, London (fig. 9). Johannes, or John, was naturalized in England in 1763 and purchased Ravenscourt in 1765.30 He must have brought the Lairesse to London at this time, and, because it would have been shipped unframed and rolled up, it now has an English pierced and gilt frame of the 1760s. Interestingly, the style is one traditionally associated with Huguenot framers, so it was perhaps made by a craftsman from within the Dutch community in London.

From d’Orville to Van Rijn

But what of the “Van Ryn” children? Jacques-Philippe d’Orville married Elisabeth Maria van Rijn (1711–1737) in 1732.31 Among the records of the Montias Database at the Frick Collection is an inventory, dated April 2, 1676, of an insolvent Pieter van Rhijn (1633–1712), who was the grandfather of Elisabeth Maria van Rijn and also a “master auctioneer for ship’s equipment of the Admiralty” [of Amsterdam] (but see below).32 Item 23 of the inventory list of twenty-eight paintings was “een schilderije uijtbeeldende de vijff sinnen met een blompot” (a painting representing the five senses with a vase of flowers). Although the painting is anonymous (and also unassessed), there are no others known to me that combine these two elements, so it seems very plausible that this Pieter van Rijn was the owner, and perhaps the patron, of the Glasgow Lairesse. The rest of his collection listed on the insolvency inventory included four sea pieces by Jan Blanckerhoff (eight to ten guilders each), a large copy after Jan Miense Molenaer (fifteen guilders), and various anonymous portraits, landscapes, still lifes, and genre scenes, valued modestly at between three and ten guilders each.33 Maybe he had fallen on hard times following the disastrous rampjaar of 1672 that saw the ruin of the Dutch economy and so many individual lives in that year, as well as a significant slump in the art market.

Further research has revealed that Pieter van Rijn was born in January 1633 and baptized in the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam. He was initially a merchant in the family firm of Reael, Thierry, and Van Rijn (later Van Rijn and Van Goor), then auctioneer of the ships and goods at Amsterdam and bookkeeper in the clearing office (and, from 1699, the first librarian) not of the Admiralty, but of the Dutch East India Company (VOC).34 He was also a Regent of the Rasp- en Tuchthuis (prison for young male criminals) in 1669. He died in May 1712.

Marten Jan Bok has kindly and brilliantly provided an extensive and conclusive genealogy for Pieter van Rijn and his children, and I am greatly indebted to him for discovering and sharing with me the crucial and conclusive information that follows in this section.35

Pieter’s paternal grandparents were Jacob Egbertsz. van Rijn (1556–1619) and Maria Claes Gaeff (1549–1633); their portraits by Cornelis Ketel are in a private collection.36 This couple’s only daughter, Griete (1585–1652), married Jacob van Neck (1564–1638), a member of the Vroedschap (Amsterdam City Council, 1621–38), a four-time burgomaster (1622–26), the admiral of the spice-trade fleet that sailed to the East Indies in 1598, and the owner of a large collection of pictures.37

But it is the younger of her two brothers, Pieter Jacobsz. van Rijn (1579–1639), who is of greater significance to us, as the father of Pieter. Pieter Jacobsz. was a cloth and silk merchant dealing in caffa, damask, and other expensive fabrics. He was a Regent of the Huiszittenhuis and served as Lieutenant in the militia company (Crossbow Civic Guard) of Captain Jacob Hooghkamer, painted by Jacob Lyon (1586/7–1648/51) in 1628 (fig. 10).38 He married no less than five times between the ages of about 20 and 53. By his third wife, he had six children, the eldest of whom had a daughter who married the artist Philips Koninck (Pieter the elder owned an example of his work).39By Pieter Jacobsz.’s fourth wife, Weyntge van Foreest (d. before 1637), whom he married in 1632, he had two further children, of whom the eldest was Pieter van Rijn.

In 1657, Pieter van Rijn married Elisabeth Bessels (1634–1708), who later became a Regentess of the Almoner’s Orphanage in Amsterdam. She was the daughter of Adam Bessels (1585–1644), a pharmacist and merchant in the Levant who along with some of his other children became mixed up in the tulip market, and whose portrait in Muscovite costume was painted posthumously in about 1670.40 Elisabeth’s mother was Margaretha Reynst (1598–1652), the daughter of Gerrit Reynst, one of the seventeen directors of the Dutch East India Company and the second governor-general of the Dutch East Indies, and sister to the very wealthy merchants Gerard (1599–1658) and Jan Reynst (1601–1646). Between them, the brothers assembled the greatest private collection of sixteenth-century Italian and seventeenth-century Dutch paintings and classical sculpture in Golden Age Holland. The cream of it was purchased from Gerard’s widow to form the celebrated “Dutch Gift” from the States of Holland and West Friesland to Charles II after his restoration in 1660.41 Lairesse famously etched the frontispiece of the influential volume of 110 prints after drawings of the sculpture collection, entitled Collectorum Signorum veterum Icones (1671) (fig. 11).42

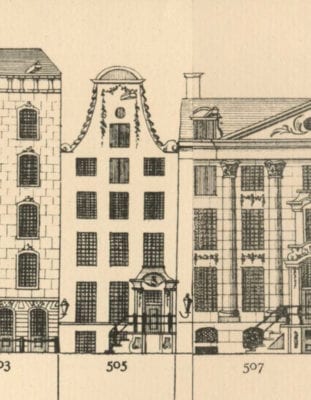

Pieter van Rijn, for whom sadly we have no portrait, lived on the Keizersgracht next to “de Stadt Gent” and opposite the brewery “de Croon” in 1661,43on the Keizersgracht near the Arminian [Remonstrant] Church in 1663,44 on Oudezijds Achterburgwal in “de Witte Leelij” near the Walloon Church in 1665,45 and on the Keizersgracht near Leidsestraat in 1674.46 At the end of his life (1708) he lived at no. 505 Herengracht near the Vijzelstraat (fig. 12), a property that descended through his family after his death until it was finally sold by Johannes d’Orville in 1760, shortly before he moved to London.

The most important facts discovered by Bok concern Pieter and Elisabeth’s ten children, born between August 1658 and August 1674. By 1668, four had died in infancy,47 but three were still alive: their second daughter, Margrieta, who was baptized in August 1659 (buried in July 1674, aged fourteen); their second son, also called Pieter, who was baptized in April 1666 (buried in January 1726, aged fifty-nine); and their third son, Adam, who was baptized in October 1667 (died in May 1741, aged seventy-three). Born after the date of the painting were their fifth and sixth daughters, Waintje (or Wendela, 1669–1746) and Clara Maria (1672–1728), and their fourth son, Jacobus (baptized in August 1674, buried in March 1676).48

In 1668, Margrieta would have been about eight or nine years old; Pieter (the younger), about two; and Adam, about twelve months. There can be little doubt that these are the three Van Rijn children in Gerard de Lairesse’s Allegory of the Five Senses in Glasgow (fig. 13).

In 1709, Pieter van Rijn the younger would marry his cousin Clara Maria van Wachtendonck (ca.1680/85–1720), daughter of an Agent of the States-General at Aachen (and granddaughter of Anna Bessels, sister to Elisabeth); they would produce two children: a son who died at age six and Elisabeth Maria, who married Jacques-Philippe d’Orville. Margrieta, sadly, died at age fourteen, just six years after the painting was made. Adam outlived them both, serving as a commissioner of the Bank of Amsterdam between 1714 and 1727. Poignantly, the four children who had died young are represented in the painting by the four putti shown playing above and below the River God fountain, itself a symbol of the passage of time, at the extreme left edge of the composition (fig. 14).

The Glasgow Painting Reconsidered

In this context, the function of Cupid may take on a more profound meaning. As Lairesse wrote: “everything originates from [Cupid] as the poets assure us.” Considering how the first peoples after the Great Flood sought some means to escape from death and immortalize their race, he asked, “Which god is more qualified in this matter to exert his influence and offer help than Cupid? Is not even Jupiter subject to his reign?”49 So while the marble Cupid here may not symbolize divine love,50 he surely stands for a love that is solid and enduring, in contrast to the transient Senses and, all too often, to the short lives of children.

In addition, the prominence of the flowers in the vase may have significance beyond their primary function of symbolizing transience and Smell by emblematizing fertility and the blossoming of youth. They appear to include varieties of rose, peony, lily, jasmine, astragalus, and viburnum, all sweet-smelling flowers that need to be carefully cultivated in a garden, perhaps an allusion to the nurturing of children in a similarly controlled domestic context. Evidently to that end, Lairesse took great care to ensure that each specific flower was clearly distinct and identifiable, albeit arguably at the expense of creating a well-balanced and realistic floral arrangement.51 The selection, disposition, and chromatic range also seem to accord with the rules he would set out in his Groot Schilderboek.52

Most significantly, the Glasgow painting now has a secure and unbroken provenance back to its presumed first commission by Pieter van Rijn (the elder) in 1668, which is rare for a Dutch seventeenth-century painting outside royal or aristocratic hands. Pieter is recorded as living successively in four different properties in Amsterdam between 1661 and his insolvency in 1676. This may indicate that he was renting rather owning them, which would in turn imply that the Glasgow painting was not made to be hung in a specific home.53 If, on the other hand, he had by 1668 bought or built the house on the Keizersgracht that he occupied in 1674, the painting could reasonably have been commissioned for it. In that scenario, and given its particular format, it is most likely to have been intended as a grand “Schoorsteen-stuk.”54

At Pieter’s insolvency in 1676, his sisters-in-law, Constantia and Maria Bessels, salvaged some of the furniture and paintings from his estate before they could be sold publicly to pay off creditors.55 The family portraits, including the Glasgow painting, were no doubt among the items retained, and they were presumably then returned to Pieter. Another sister-in-law, Clara Bessels (1632–1697), left the house at no. 505 Herengracht (built 1683) to Pieter van Rijn the elder’s children—most likely so that his creditors couldn’t acquire it—for this was Pieter the elder’s address in 1708, and he may have lived there, with Clara and her husband, for several years before that. If so, the Glasgow Lairesse may have hung for many years in this property, which was inherited in 1746 by Johannes d’Orville from his great-aunt Wendelina (1669–1746), the last of the Van Rijns. Indeed it probably remained there until John finally took it to England in the 1760s.

At this point it is also worth considering a little-known painting by Lairesse in Havana, of identical dimensions to the Glasgow Allegory, for which Roy proposed a similar date and which could be its pendant (fig. 15).56 This painting is ostensibly an Allegory of Spring, but Roy is surely correct to interpret it as a rather more complex vanitas subject on the theme of love. There are parallels in the architectural backdrop, the binary composition, the central woman (who is apparently the same model as in the Glasgow painting), and, above all, the possibility that the three children (aged about two to six) on the right are portraits, while the six on the left, near symbols of death, represent deceased infants. However, the scale of the principal figures does not match up, making these unlikely pendants, and as yet no link has been found to Pieter van Rijn the elder’s immediate family.57 If there is a connection to him and the Glasgow painting, it is yet to be explained.

Some further questions remain. Firstly, why did Pieter van Rijn choose Lairesse to portray his children? Few, if any, portraits by him are known to predate the Glasgow picture,58 so his reputation in this sphere must have been limited. Part of the explanation must lie in the fact that in 1668, the date of the painting, and since 1665, Pieter’s address on the Oudezijds Achterburgwal (now nos. 157–167) was close to the Walloon Church, of which the Liégeois Lairesse had also been a member since 1665;59 it was also close to the artist’s own home on the Nieuwmarkt.60 In addition, the prominent dealer Gerrit Uylenburgh (ca.1625–1679), for whom Lairesse worked briefly upon his arrival in Amsterdam, is said to have praised and showed the artist’s work to connoisseurs. Perhaps Pieter was among them, since Uylenburgh certainly knew his aunt, Anna Reynst, the widow of the great collector Gerard Reynst, for whom Lairesse made an engraved title page in ca.1670, again drawing from Ripa.61 Also, by 1668 Lairesse had met and indeed made engravings for the dramatic poet Andries Pels, who would help found the art/literary society Nil Volentibus Arduum in the following year. This society consisted largely of “influential citizens and intellectually ambitious members of the ruling families,”62and Lairesse’s association with such people—who may have included Pieter van Rijn—naturally assisted with the rapid advance of his social position.

Lairesse’s clear, idealizing style drew on both the Poussinian classicism of his master, Bertholet Flémal (and, via print reproductions, of Poussin himself), and the native Dutch tradition of classicism that had become especially popular in court circles and among the wealthy elite from the 1650s. Called indeed the “Dutch Poussin,” acclaimed as the “New Apelles” by Willem III, and sometimes even compared with Raphael, Lairesse would go on to produce many large-format history paintings and allegories. By the 1670s, he had become one of the most popular artists in the Dutch Republic, painting several overmantels or cycles of paintings to decorate the interiors of the houses of wealthy Amsterdam merchants and regents. It was therefore probably more his skills and ambitions as a history painter than as a portraitist that first won him the attention of Pieter van Rijn.

Liedtke’s comments on the Apollo and Aurora in New York apply equally to the Glasgow Allegory: such paintings “clearly demonstrate why Lairesse was so successful in Amsterdam. Combining classical subjects, contemporary relevance, idealized portraiture, and the latest pictorial style, he gave sophisticated patrons pictures that are masterfully composed and painted, and—despite their show of learning—more accessible than the great majority of works in this vein.”63

Presumably patron and artist discussed the particular iconography of the Glasgow Allegory of the Senses, for which there are few precedents as a subject for child portraiture.64 One factor may have been that some of the primary attributes of the Senses could suitably and plausibly be held by young children, and indeed there is an appropriate charm in them doing so. But of overriding significance, no doubt, was the overall message of the painting: the enduring power of eternal love over fleeting senses and life itself.