Recent scientific analysis of two genre paintings by Johannes Vermeer at the National Gallery of Art in Washington (Woman Holding a Balance and A Lady Writing) has uncovered a level of freedom and spontaneity in Vermeer’s preparatory painting stages that was not previously known. Researchers built on decades of research and used a suite of new, noninvasive analytical techniques to image Vermeer’s painted sketch and underpaint—layers hidden below the paintings’ surfaces—more clearly and precisely than was previously possible. Here we analyze and interpret our findings in the context of Vermeer’s career and in relation to works by his peers, high-life Dutch genre painters of the seventeenth century. For further exploration, see “Methodology & Resources,” “Experimentation and Innovation in Vermeer’s Girl with the Red Hat,” and “Vermeer’s Studio and Girl with a Flute” in this issue.

Introduction

Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) is celebrated for his uncanny ability to distill daily life into moments of almost preternatural calm—a talent derived as much from his compositional sensitivity as from his tranquil paint surfaces. And yet below the surface, a remarkably different vision exists. As a recent comprehensive technical study of all four works by and attributed to Vermeer at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, has revealed, Vermeer worked with extraordinary freedom in the early stages of his creative process. Now hidden below the surface, this process fundamentally shapes the tranquil images we see today.

Vermeer depicted commonplace activities with a sensibility unmatched by his contemporaries. While Gerrit Dou (1613–1675), Gerard ter Borch (1617–1681), Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667), and Frans van Mieris (1635–1681)—who, like Vermeer, specialized in so-called “high-life” genre scenes—typically relied on rhetorical gestures, ancillary figures, emblematic references, and other pictorial devices for emotional effect, Vermeer depended less on such elements. Instead, he examined the world around him with a different intent, scrupulously attentive to light, color, and compositional harmony. His distinctively personal manner of painting infused even the simplest actions and environments with transcendent beauty.

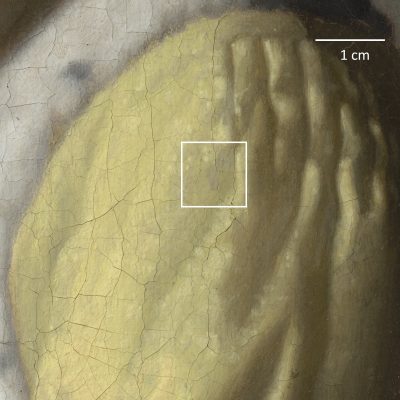

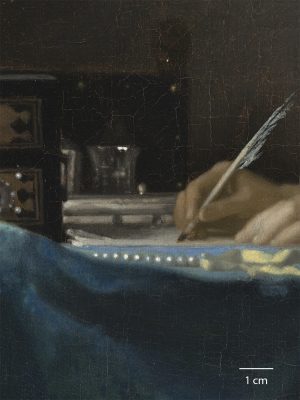

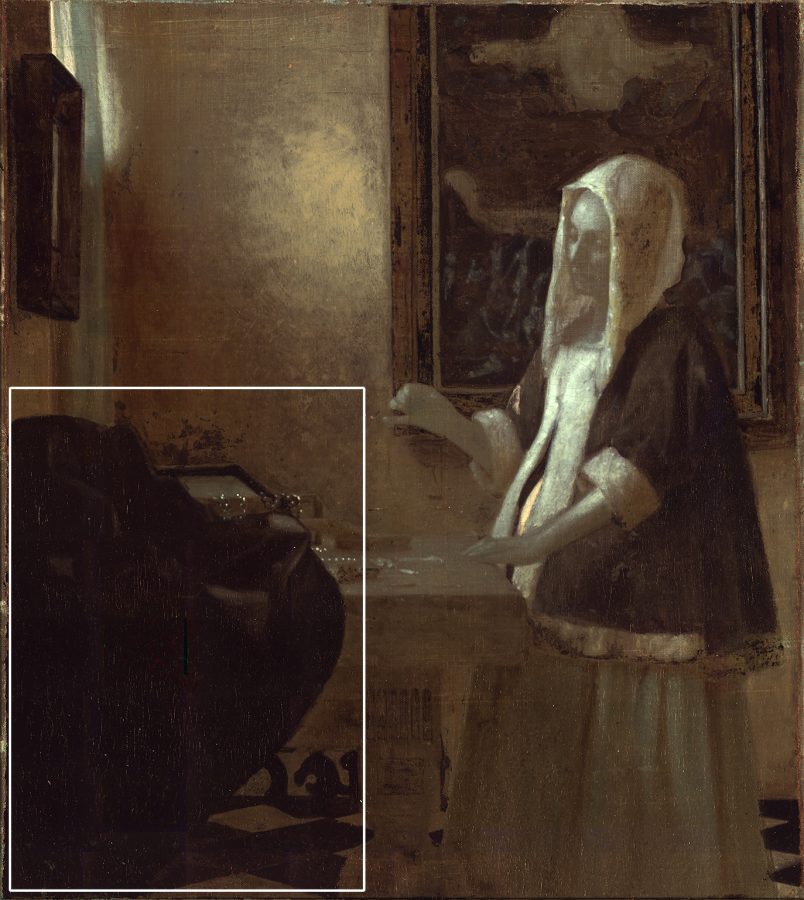

In A Lady Writing, a young woman interrupts her task to meet the viewer’s gaze (fig. 1). Her quill has fallen back in her hand and her calm eyes examine us, intruders who have happened upon this utterly quiet tableau. An unseen light source illuminates the scene with a diffuse glow, animating a hushed color harmony of muted yellows with warm gray and taupe. Smooth, nearly imperceptible brushstrokes graze the curves of the woman’s face to describe subtle gradations of light, and the sleeve of her butter-colored housecoat shimmers with barely seen touches of a lighter yellow.

Woman Holding a Balance centers on a figure seemingly lost in thought (fig. 2). The viewer is held at a distance by the crumpled tablecloth that forms a gentle repoussoir. Vermeer’s subtle rendering of light defines the privacy of the space beyond that barrier: daylight filtering through the window at upper left caresses the woman with soft highlights and picks out glistening reflections on the empty pans of the balance, but the illumination is tightly focused. In the shadowy foreground, just a few blurred highlights shape the tablecloth that spills over into the viewer’s space.

In this article, we focus on these two high-life genre paintings by Vermeer to show how the discovery of Vermeer’s bold handling in his paintings’ initial phases contravenes simplistic assumptions about his process as suggested by his refined surfaces. This new research also sheds light on how his painting process was fundamental to those aspects of his personal style that distinguish him from his closest contemporaries. Elsewhere in this issue of JHNA, we argue that the freedom of his underpaint eventually shaped his approach to painting tronies (bust-length paintings of imaginary figures) and, through them, found repercussions in his later, more strongly abstracted works.1 Comparing and integrating results from various technical examinations, our interdisciplinary team of researchers has built a more refined understanding of how the artist worked, the choices he made regarding the process and materials used to construct a given painting, and their implications for the final aspect of his exquisitely crafted paintings. The findings of our in-depth analysis are presented in detail in the scientific literature.2 In this special issue, we interpret the findings in an art-historical context.

A History of Study at the National Gallery

For almost fifty years, the National Gallery has supported a tradition of scholarly inquiry into Vermeer’s artistry, process, and relationship to other high-life genre painters.3 The exhibition Johannes Vermeer (1995–1996), co-organized by the National Gallery and the Mauritshuis, The Hague, was an important moment in Vermeer studies. Bringing together the largest number of the artist’s works ever shown in a public institution until that time, it offered an unprecedented opportunity to study his work collectively and in depth, from a range of perspectives that included studies of his materials and techniques.4 A more recent contribution was the exhibition Vermeer and the Masters of Dutch Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry (2017–2018), co-organized with the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, and the Musée du Louvre, Paris. That show placed Vermeer within larger social, economic, aesthetic, and technical trends of seventeenth-century Dutch painting, offering a more nuanced approach to his “uniqueness.” It explored the idea that Vermeer, while standing apart from his contemporaries in many respects, was not an isolated genius but part of a network of elite artists working at the highest level of the Dutch art market in the third quarter of the seventeenth century.5 Detailed analysis of archival data by Adriaan Waiboer, Piet Bakker, Teuntje van de Wouw, and Marit Slob mapped the personal and professional relationships between all of these artists.6 Technical research has tended to focus on individual artists, or even on individual works, but Melanie Gifford and Lisha Glinsman’s comparative technical research for the exhibition took a broader view, using material evidence to further explore artistic relationships where no archival evidence is available.7

Building on this enriched contextual understanding, the National Gallery’s history of art-historical and material research into Vermeer, and the work of colleagues at other institutions where similar explorations are underway,8 we recently undertook a comprehensive technical study of all four works at the National Gallery by or attributed to Vermeer—A Lady Writing, Woman Holding a Balance, Girl with the Red Hat, and the controversial Girl with a Flute—to understand better how his painting practices contributed to the formation of his personal style.

We now have a clearer sense of how Vermeer created the distinctive visual qualities of his paintings. Chemical imaging techniques have yielded new insight into Vermeer’s use of pigments throughout his paintings and allowed us to visualize his preparatory paint layers (hidden below the surface) more comprehensively than previously possible. Although his painting surfaces (like those of other high-life genre specialists) are far more finished than paintings by contemporaries like Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), for example—whose loose brushwork allowed the underlayers to play an important role in the final image—our technical study of the National Gallery’s works by Vermeer revealed that his initial laying out of a composition was surprisingly free and robust.

Vermeer and the High-Life Network

For most of his mature career, Vermeer and his peers in high-life genre painting—such as Dou, Ter Borch, Metsu, and Van Mieris—were among the mostly highly paid painters working in the Dutch Republic. They created idealized images of daily life that presented elite art collectors with a vision of well-appointed interiors furnished with imported carpets, porcelains, and tooled leather wall hangings, inhabited by women (and sometimes men) clad in pristine, shimmering garments who write letters, play musical instruments, or engage in other genteel activities.9

After this new type of genre painting emerged around 1650, artists and patrons seem to have come to a collective understanding of its defining characteristics. Not only did these artists depict a set of elegant subjects that defined the high-life genre style, but, as Gifford and Glinsman’s technical research determined, certain essential materials and painting practices evidently served as a threshold for entry into this elite art market. This research also found that, within the parameters of their collective style, virtually all these artists adopted a few unique and recognizable practices that served to trademark their works in a highly competitive market.10 Distinguishing between the material traits that Vermeer shared with most other high-life genre specialists and those he used to set his work apart allows us to focus here on those painting practices that formed the basis of his personal style.

One of the material traits shared by almost all these artists is the use of costly pigments, including high-quality red lake, such as cochineal, and ultramarine, the rich blue made from lapis lazuli.11 Although scholars often have cited Vermeer’s use of ultramarine as an identifying feature of his paintings, in reality nearly all these artists used this precious blue pigment. Those who achieved the highest prices for their works often used ultramarine profusely, while those who realized somewhat lower prices used it sparingly but strategically, reserving it for small details that would catch the eye of a discerning collector.12 Another widely shared trait was the fine-scaled brushwork key to creating the paintings’ heightened naturalism. Patrons and collectors celebrated these high-life genre artists for the precision of their handling and the apparent verisimilitude of their works. Quintessential fijnschilders (“fine painters”) like Dou or Van Mieris, operating at the highest end of the market, even boasted of their labor-intensive technique, presumably as a marketing strategy.13

These precious paintings were not, however, interchangeable, and the ability to discern fine distinctions of both personal and collective style was considered the mark of an elite connoisseur. Connoisseurs visited celebrated collections and painters’ studios, training themselves in the nuances of artistic style, and some buyers even specialized in collecting the work of a favorite artist.14 In 1665 the Leiden collector Johan de Bye held a public exhibition of his twenty-seven paintings by Dou, while in Delft, the wealthy collector Pieter van Ruijven (often described as Vermeer’s principal patron) came to own twenty-one of Vermeer’s works, a substantial part of the thirty-five known paintings.15 Like his fellow artists, Vermeer adopted certain painting practices to create a distinctive personal style, but an essential characteristic of his trademark style deliberately flouted one important shared standard of high-life genre paintings: the emphasis on precise, refined brushwork.

Vermeer’s subjects were elegant and his materials costly, but his brushwork, however refined, is notably different from that of his competitors. Modern viewers often see a photographic accuracy in Vermeer’s compositions, but to seventeenth-century collectors of high-life genre his studied imprecision must have appeared strikingly free, suggestive rather than descriptive. A comparison to works by Van Mieris (fig. 3) and Metsu (fig. 4) highlights Vermeer’s distinctive approach. Among his contemporaries, Van Mieris set the standard for meticulously recorded high-life genre paintings, describing every luxurious detail of his elegant interiors using a minute, sharply defined application of paint.

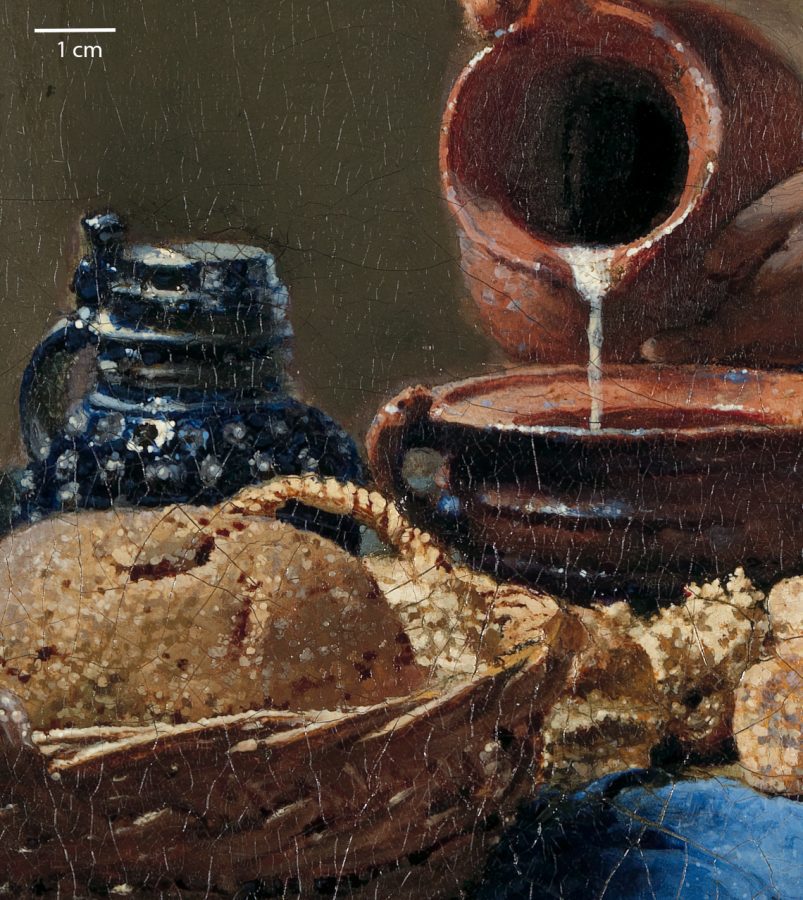

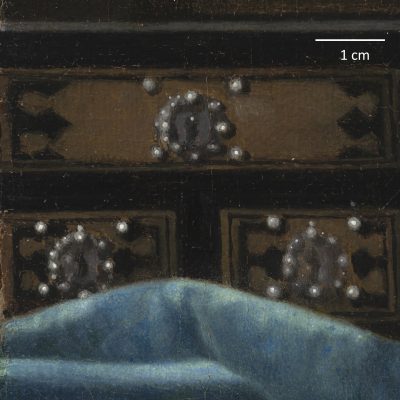

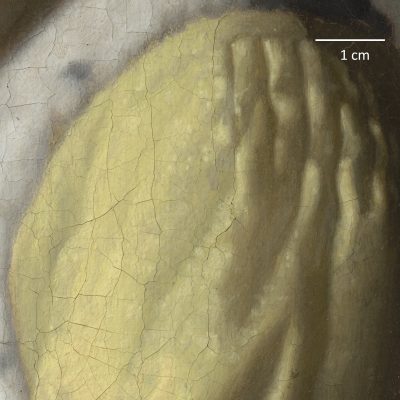

He worked over many days, waiting for each brushstroke to dry as he built a composition of crisp, distinct details (fig. 5). Metsu painted more efficiently but still adhered to the standard of precise brushwork. After quickly painting an entire tabletop with still life details, working wet into wet, he adroitly created sharply focused details without resorting to Van Mieris’s slow painting process, simply adding fine black contour lines to throw his forms into sharp relief (fig. 6).16 Vermeer took a different approach. He too worked wet into wet, but apparently not as a time-saving strategy; he applied his final paint with slow discipline. His use of this technique blurred details with strokes of fluid paint that, relative to those of his peers, seem quite broadly handled. Rather than emphasizing material details, as Van Mieris did, he used this blurred handling to depict light itself as it enveloped and inflected the figures and furnishings in those same domestic spaces (fig. 7). Paradoxically, perhaps, it is precisely this subtle blurring of forms that makes Vermeer’s paintings look so convincingly real. While the crisp illumination of works by Dou, Van Mieris, and others emphasizes the staged perfection of their painted worlds, Vermeer breaks down that barrier by recreating in his paintings the same light that suffuses the world we inhabit.

Vermeer’s rendering of light was a key element of his personal style, although the ways in which he achieved this varied over the course of his career. Early in his career, in paintings such as The Milkmaid (figs. 8, 9), this quality was expressed in large-scale dots of highlight. He continued throughout his career to abstract the depiction of light by using circular highlights, but in late works such as A Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid, that abstraction of light expanded to include fabrics sculpted by broad planes of light and shade (figs. 10, 11).

Since the 1960s, it has been suggested that Vermeer’s characteristic circular highlights could have derived from images seen in a camera obscura.17 He was almost certainly familiar with this optical device, which uses a pinhole or lens to project a scene onto a viewing surface. In A Lady Writing, the introduction of these distinctive highlights on polished surfaces—such as pearls and the metal studs of the jewelry box—indeed evokes how a camera obscura would show the optical effect known as “circles of confusion” or halation (fig. 12). But Vermeer brought this visual vocabulary to unreflective surfaces as well (fig. 13),18 a strong indication that he was not simply replicating a projected image. From the start of his career, he depicted abstract, rounded highlights even on matte fabric, evidence that this way of expressing light was integral to his mode of expression.19 The images from a camera obscura may have resonated with Vermeer, causing him to adapt their visual qualities selectively to his own artistic ends.20 When he touched rounded highlights into wet paint to depict the tucked sleeve of a yellow jacket, these fluid circles do not describe the texture of the fabric; they are an abstraction of light itself.

Painters seem to have catered to collectors’ focus on the individual by deliberate quotations of aesthetic and technical qualities that distinguished each other’s work. They evoked fellow artists’ compositions and also adopted distinctive features of their personal styles.21 Although Vermeer’s output was comparatively small, quotations of his work by fellow artists suggest that the visual qualities of his paintings were well known in these circles.22 When Vermeer’s contemporaries referenced his works, they borrowed characteristic details, such as specific costumes or furniture that appeared in his compositions, and, on occasion, his distinctive way of handling paint.

The visual quality imparted by Vermeer’s painting technique also served as a style signifier. In Woman Reading a Letter (fig. 14), Gabriel Metsu deliberately and adroitly adduced elements characteristic of Vermeer’s work.23 After he first painted the woman wearing a reddish jacket typical of his own oeuvre, Metsu reworked this feature to replicate the iconic yellow jacket that appears in several of Vermeer’s paintings (fig. 15). However, Metsu did not set aside his own, efficient painting practices in favor of the slow, fluid paint application, finished with soft, circular highlights, that Vermeer used to create the yellow jacket in A Lady Writing. Always efficient, he quickly repainted the jacket with blocks of yellow light and shade, and he quoted Vermeer’s trademark circular highlights elsewhere. As a final touch, he simply sprinkled dotted highlights onto the prominent, cast-off shoe in the foreground (fig. 16).

Vermeer Below the Surface

The smooth final surfaces of Vermeer’s paintings embody a characteristic calmness that seems to match the mood of the scenes he depicted and gives no indication of the working processes that preceded them. However, new chemical imaging techniques, combined with microscopic examination, have given us an unprecedented opportunity to visualize earlier stages of Vermeer’s creative process. Moving below the distinctive surfaces of Woman Holding a Balance and A Lady Writing allows us to explore new evidence of how Vermeer created his remarkable evocation of light and how the fundamental design stages of his paintings, now hidden from view, presaged his final, luminous touches. The research methods discussed in this study offer two avenues of approach: analysis both at specific points on the paintings (including sampling and non-sampling methods) and across the entire paintings. This is a brief overview of our methods; full details are found in “Methodology and Resources” elsewhere in this issue. Further information can be found by clicking on the figures, which illustrate the main techniques used in this article.

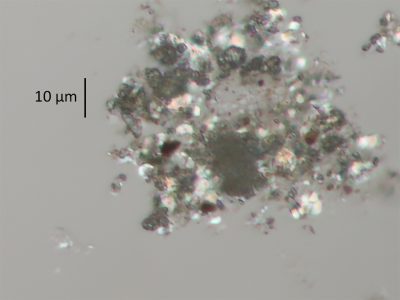

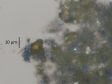

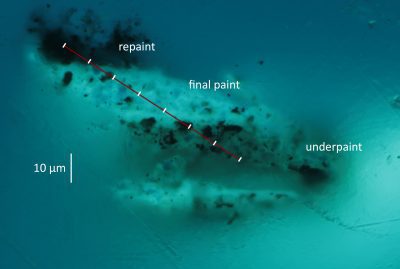

We gathered detailed information at specific points through microscopic analysis of a few paint samples: polarizing light microscopy (PLM) identified individual pigment particles in a few grains of paint collected from the paint surface (fig. 17); light microscopy of paint cross sections showed the layer structure (fig. 18); and analyzing those samples using scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) gave information on the pigments in each layer. It was also possible to infer pigment mixtures at specific points without taking samples using X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF)—which, like EDS, identifies chemical elements present—and fiber-optic reflectance spectroscopy (FORS), which gives information on electronic transitions and molecular structure from which color values can be determined.

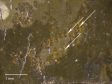

Chemical imaging performed across entire paintings offers a powerful way to visualize the distribution of painting materials, which can reveal aspects of Vermeer’s paint handling for specific parts of the composition. We inferred where pigments were used throughout each painting based on chemical elements with X-ray fluorescence imaging spectroscopy (XRF element mapping) (fig. 19), or identified pigments based on electronic transitions and molecular structure information obtained with reflectance imaging spectroscopy (RIS). In multispectral infrared reflectography (MS-IRR), three infrared images are combined in a false-color infrared reflectogram (IRR) (fig. 20) that separates pigments more clearly than is possible with traditional infrared reflectography.

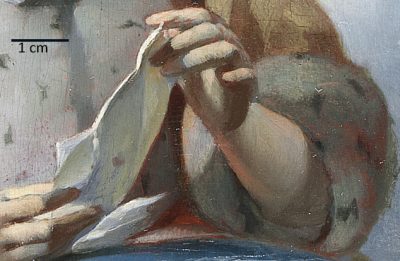

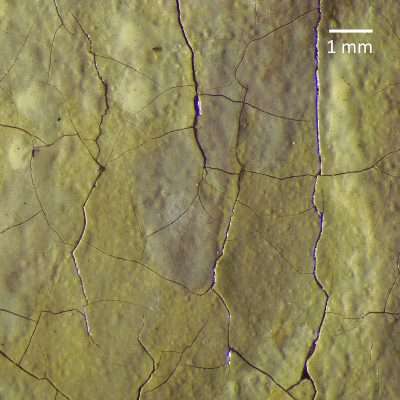

Finally, the information collected through these varied analytical methods was interpreted in the context of the paintings themselves, studied at high magnification. Because it is essential to compare paint handling at the same scale, when this evidence is presented in close details and photomicrographs scale bars indicate the magnification (fig. 21).

Canvas and Ground

In choosing his painting support and ground, the foundations of his refined surfaces, Vermeer followed practices that were standard among Dutch artists and used supplies that were widely available from specialist art suppliers. Nearly all of Vermeer’s extant paintings are on finely woven canvases.24 Canvas weave analysis shows that in several cases, two or more of his paintings used canvas from the same bolt. These findings include pairs of paintings painted within a short time, some being probable pendants, but also some canvas matches that apparently span several years, suggesting that he bought supplies in batches that he used over time.25 He probably bought his canvases already prepared with a ground layer from a specialist primer.26 In choosing a surface on which to build his composition, he favored light-colored grounds of lead white and chalk lightly tinted with earth colors and black: a warm gray for A Lady Writing, for example, and buff for Woman Holding a Balance.27

We are not certain why Vermeer, unlike many of his peers in high-life genre painting, nearly always chose canvas as his support.28 By the middle of the seventeenth century, most Dutch artists worked on canvas, a painting support that was lightweight and less expensive than the wood panels common earlier in the century. Some genre painters, like Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684) and Metsu, frequently used canvas supports, especially for larger works; but others, notably Dou and Van Mieris, chose wood and sometimes copper supports, whether because their works’ smaller dimensions made this preferable or because they sought a smoother surface for their fine-scaled brushwork. Perhaps this is another sign that Vermeer aspired to a more suggestive visual effect than the performatively minute handling of artists like Dou and Van Mieris.

Painted Sketch

Typically, seventeenth-century Dutch artists planned out their compositions directly on the prepared ground. Some began, as earlier generations of Netherlandish artists had, with a careful underdrawing in chalk, charcoal, or ink, but by the mid-seventeenth century the fundamental design stage for many painters was a monochromatic brown painted sketch (This is sometimes called the doodwerf [“dead color”], but we avoid that term here, since both modern and historical writers have used it in more than one context, some referring to the monochromatic painted sketch but others to the colored underpaint stage that often followed it.).29 The character of this sketched design stage varied from one artist to another. Although some artists, such as Rembrandt, worked with a loose handling of paint that allowed the painted sketch to play a visible role in the final image, high-life genre painters tended to conceal this preparatory stage beneath the precise final surfaces of their paintings. For example, to achieve his signature level of fine detail, Van Mieris prepared his compositions with a brushed design in two or more stages. Infrared reflectography of his paintings shows that he first laid out the design with brisk strokes and then elaborated many details with fine lines, including delicately hatched shadows—all of which was deliberately hidden by the surface paint.30

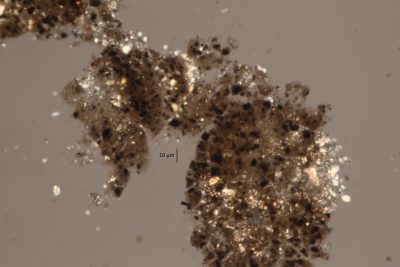

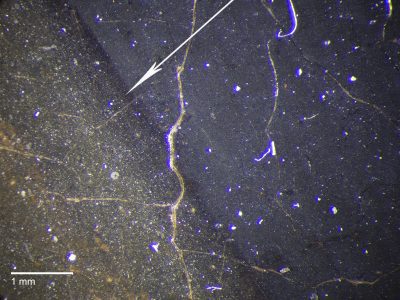

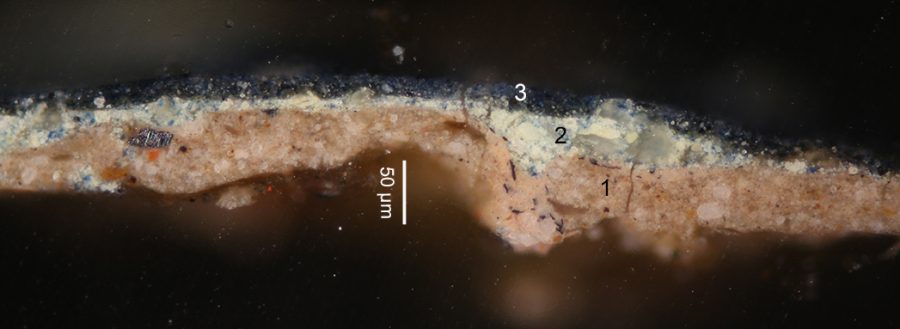

In Vermeer’s The Art of Painting (1666–68; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), summary notations in white chalk can be seen in the unfinished work on the easel, suggesting that Vermeer himself may have initially planned the placement of key compositional forms with such a drawing.31 However, technical examination of the National Gallery’s paintings reveals that he primarily laid out his compositions with the standard monochromatic brown painted sketch.32 Although he brought his paintings to a high level of finish, he occasionally left minute openings through which we see evidence of the brown sketch with a stereomicroscope. Microscopic analysis of a sample from one of these openings in Woman Holding a Balance found a dark brown earth pigment (figs. 22, 23),33 but Vermeer’s sketch paint is difficult to visualize using the available methods of technical imaging. Infrared reflectography revealed evidence of Van Mieris’s preparatory design because it includes carbon-containing black pigments, but in our study, MS-IRR did not show evidence of Vermeer’s sketch because he did not consistently add black to his brown paint. An XRF iron map can plot the location across the painting of earth pigments, which are primarily composed of iron oxides, but the sketch itself cannot be isolated, because iron-containing earth pigments are also present in the ground layer beneath the sketch and in many areas of final paint that lie over it. Likewise, an XRF map for manganese, which could show the manganese oxide that is present in certain brown earths such as sienna and umber, also records these pigments when they appear in the ground layer, making it difficult to distinguish between sketch and ground.34 However, using high magnification to study Vermeer’s paintings, the rare openings that he left in his painted surfaces do afford glimpses of the painted sketch, which give evidence of his brushwork in this preliminary design stage.

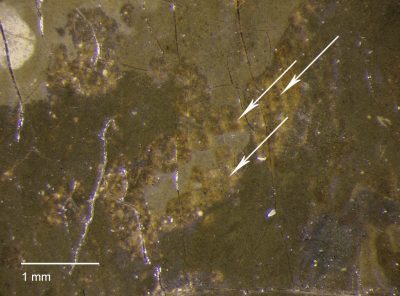

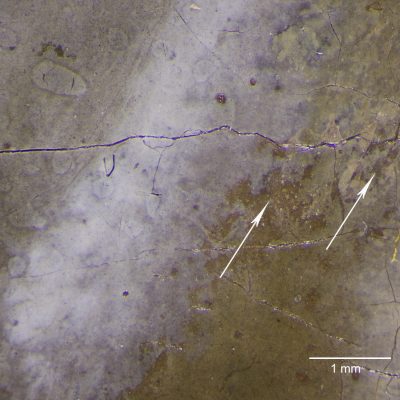

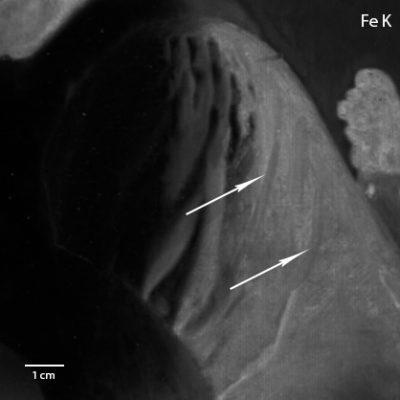

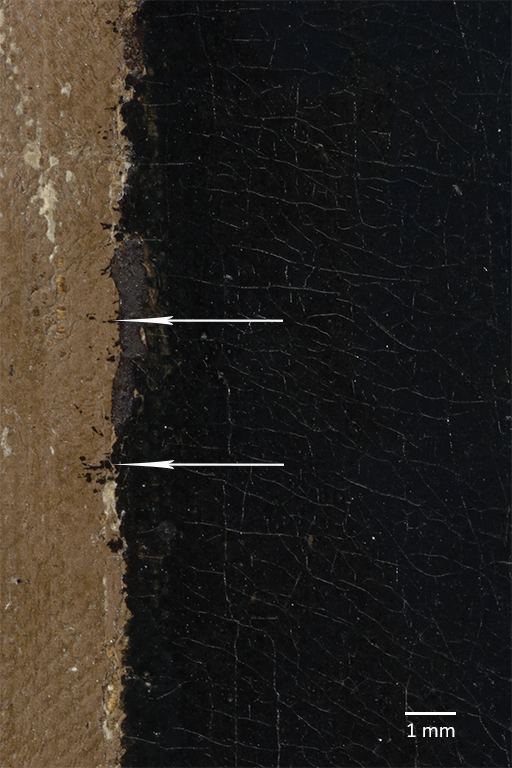

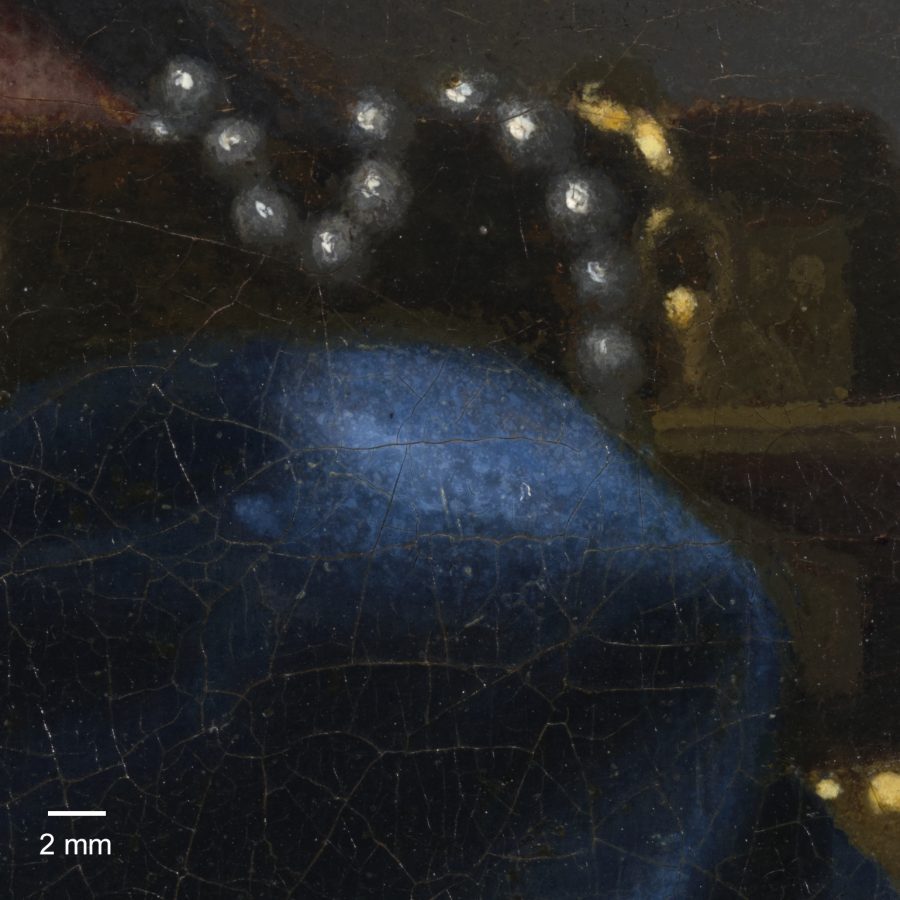

By comparison with a fijnschilder such as Frans van Mieris, the handling of Vermeer’s painted sketch seems bold. He seems to have used the sketch to lay out the details of his composition, as Van Mieris did, but he worked more broadly. In Woman Holding a Balance, a minute opening below the woman’s hand that rests on the table reveals two parallel lines of brown sketch paint, probably where the hairs of Vermeer’s brush separated as he swept it along the contour of the hand (figs. 24, 25). Just as important, Vermeer used his painted sketch to define and emphasize the play of light. Where Van Mieris hatched shadows in a graphic fashion, Vermeer brushed out broad zones of shadow and left the light-colored ground exposed to serve as highlights. In a lion’s-head finial, one of the most freely painted passages of A Lady Writing, Vermeer left evidence of his loose brushwork in the painted sketch where he blocked out an area of shadow. Between the solidly handled strokes of final paint, small openings reveal streaky brown paint. Here, too, the lines of paint are evidence of a paintbrush fanned out by the pressure of quick paint strokes (figs. 26, 27).

Underpaint

Like most of his contemporaries, Vermeer next laid out an underpaint that he painted directly on the brown painted sketch. For those who have spent hours contemplating the refined surfaces of Vermeer’s paintings, the forceful character of the underpaint below the surface, as revealed by technical research, may come as a surprise. In fact, freely brushed underlayers have been cited as evidence against Vermeer’s authorship of an unfinished painting below the Girl with the Red Hat (ca. 1669), as we discuss elsewhere in this issue.35 In the underpaint, Vermeer further developed the play of light and shadow he first laid out in the painted sketch, but in this stage, he also planned the colors of his composition. Although published research sometimes describes colored paint glimpsed below the surface as “local underpaints,” Vermeer does not seem to have worked on isolated areas of his compositions, completing all paint layers of a tablecloth, for example, before beginning to paint the figure. Where paint layers overlap, it is clear that he completed the underpaint for the entire composition as an independent stage that our research shows is strikingly different in character from his final paint.36 Perhaps most important, the brushwork of his underpaint established the physical structure of his composition, with passages of thicker paint modeling the forms in low relief.37

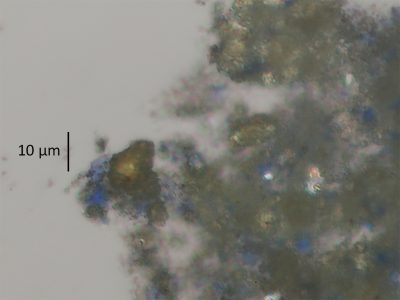

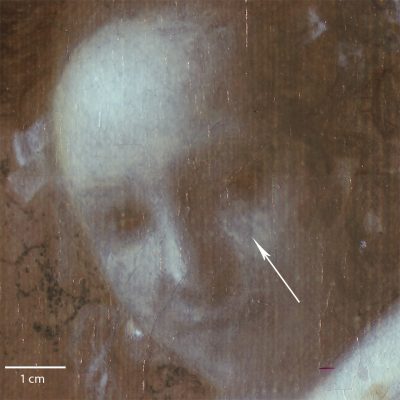

The tonal transitions visible today in the woman’s face in A Lady Writing exemplify Vermeer’s remarkable finesse (fig. 28). On the forehead, he blended his paint imperceptibly from light into shadow, and he modeled the curve of the shadowed cheekbone with delicately interwoven, threadlike strokes (fig. 29). However, below the chin, a tiny gap in the final paint—scarcely visible to the naked eye—reveals underlying paint of a very different character. Under high magnification, it is clear that the paint below incorporates coarsely ground pigments brushed out with vigorous strokes that left a furrowed path far more textured than the surface (fig. 30). We know that Vermeer occasionally left narrow gaps like this between compositional forms as a deliberate strategy.38 Here he exploited the underlayer: just as his wet-into-wet brushwork was a repudiation of hard-edged detail, this elusive glimpse of texture below the surface deliberately blurs the contour between the woman’s face and the fur collar of her jacket. Gifford’s previous research used episodic evidence like this to highlight the rough character of Vermeer’s underpaint, which is remarkably textured in comparison to the subtle final surface we see today.39

Vermeer’s Handling in the Underpaint

The imaging techniques employed in the present study have revealed much more of the underpaint of Vermeer’s paintings, giving new insights into the character of this hidden stage in his creative process. XRF element mapping creates images that plot the distribution of individual chemical elements across a painting, from which we can infer the artist’s use of specific pigments. In conjunction with magnified examination of the surface and analysis of cross-section samples, mapping can provide information about the paint layering structure, sometimes offering a vivid image of the paint handling in the preparatory stages.

At the underpaint stage of A Lady Writing, Vermeer laid out the tucked sleeve of the yellow jacket by noting the pattern of light and shade in broad, schematic form. He brushed out the shadowed back of the sleeve with ochre, an iron oxide pigment recorded in the XRF iron map (figs. 31, 32). In that map we also see where Vermeer dragged a wide brush through the still-wet ochre, wiping away paint to leave a few wide troughs. With these quick gestures, his brush left broad lines that created just a summary indication of folds, utterly unlike the subtle depiction of folds in the final paint.

In the underpaint, Vermeer also provisionally indicated a lighter-colored fold of the sleeve, possibly a highlight, with just a few broad strokes of coarsely ground lead-tin yellow (fig. 33). His choice of material also diverged from his finely ground final paint, where he may also have used a different grade of lead-tin yellow (fig. 34).40 With magnification, the texture of these hasty strokes is visible through the final surface paint (fig. 35).

In the underpaint, a false-color IRR also reveals the quick brushwork and the surprisingly abrupt tonal transitions with which Vermeer depicted the fall of light in the figure of A Lady Writing. Unlike traditional infrared reflectography, MS-IRR creates a false-color IRR using three narrow infrared spectral band reflectance images chosen to visually emphasize features of interest. Infrared light penetrates upper paint layers to show underlayers, and while the colors rendered in the false-color IRR do not correlate with what may be observed in normal light, they do help to distinguish between various materials that might look confusingly similar in a traditional reflectogram.

In comparison to the final surface of A Lady Writing, the false-color IRR of the forearm shows exaggerated contrasts of light and shadow in the underpaint, from dabbed white highlights to dark brown shadow (figs. 36, 37). A detail of the face shows that Vermeer used a quick and summary touch in his underpaint, daubing thick white highlights onto the forehead and cheekbones (figs. 38, 39).

Magnified examination confirms the importance of strong colors at this stage of the painting process. In Woman Holding a Balance, Vermeer also modeled the flesh tones in the face with a high-contrast underpaint in varied colors. In the chin and neck, glimpses of the underpaint are visible through intentional gaps: shades of a warm brown at the throat shift to a lighter red-brown color and warm tan closer to the chin.41 Although Vermeer’s cool final paint muted these strong colors, they still contribute to the final appearance, gently warming the pale face (figs. 40, 41).

In places, Vermeer’s underpaint combines forcefully textured brushwork with strong contrasts in both light and color, creating passages whose character shapes the play of light in the delicate final image.42 In A Lady Writing, Vermeer depicts a wide tonal range in the play of light on the crumpled tablecloth. While bright light throws folds of fabric on the tabletop into sharp relief, half-light brings the shadowed side of the table to life, drawing out subtle folds and swags in what would otherwise have been a solid, dark mass. He prepared these delicately differentiated light effects with a bold underpaint, laying out lighted areas with thick, vigorously brushed highlights rich in lead-tin yellow while leaving the brown painted sketch to represent the shadows. A cross section taken from the edge of the painting shows the application of the yellowish underpaint—ranging from thick to almost imperceptibly thin—which Vermeer muted with a smooth layer of dark final paint to create a half-shadow on the lighted tabletop (figs. 42, 43).

The XRF tin maps record Vermeer’s varied handling, with brushwork that is far more energetic than the calm surface would suggest, in the deep swag of the hanging cloth accented with a sweep of stippled dabs of the brush (fig. 44).

In his final paint, Vermeer softened the sharp contrasts—the XRF lead map that records lead white pigment mainly in surface paint (the M-line energy) shows the smoothly modeled, whitish highlights of the final image (fig. 45)—but the high-contrast, brightly colored underpaint glimmers through the final paint.43 It enlivens the folds of the cloth atop the table and contributes color and texture to the subtle modeling in the shadowed repoussoir.

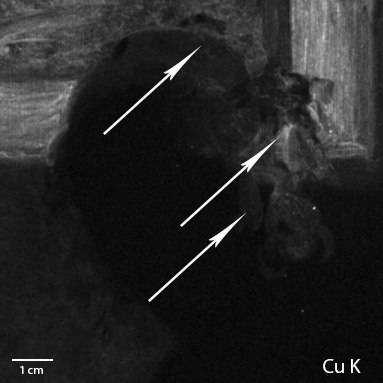

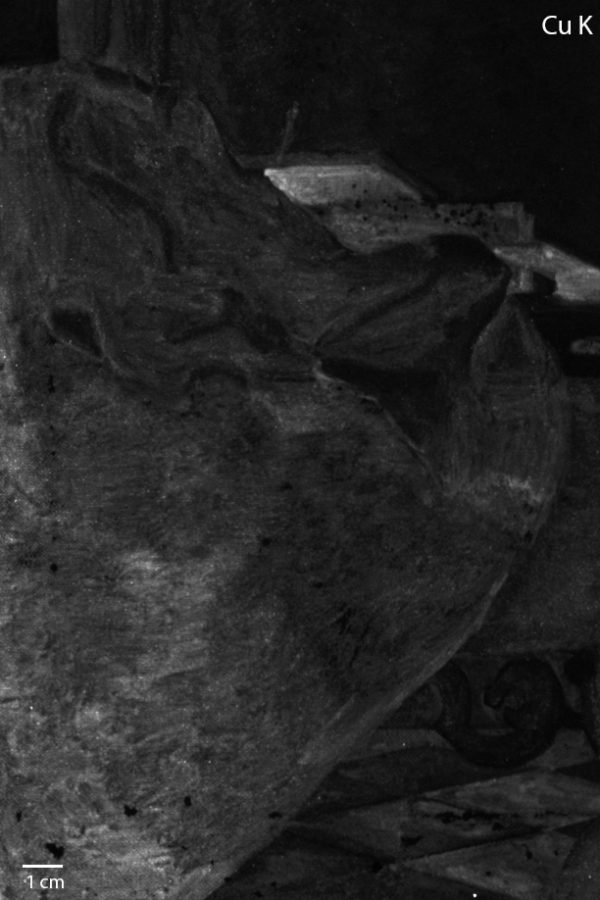

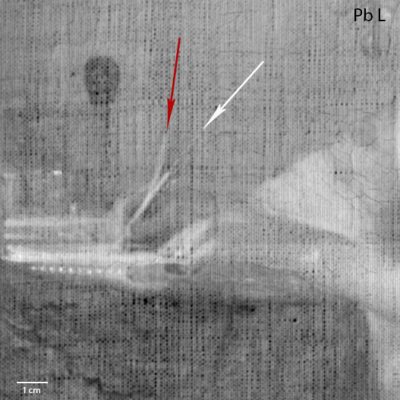

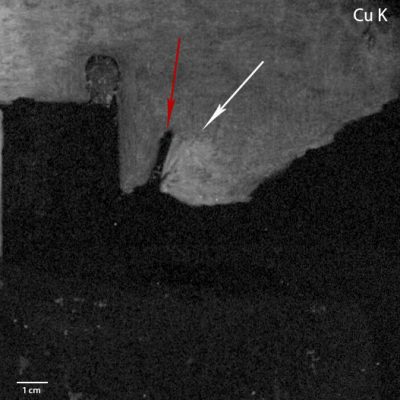

Copper Drier

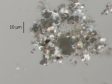

Our analysis also has uncovered new evidence that the paint Vermeer prepared for the underpaint stage was materially different from his final paint, evidently specifically formulated to enable him to complete this phase of work more quickly. In the tablecloth of Woman Holding a Balance, the XRF copper map shows folds that differ from the final image, evidence that the copper-containing paint corresponds to an underlying paint layer (figs. 46, 47).44 The standard presentation of XRF maps is a grayscale image in which whiter or brighter areas signify a stronger signal; here, white areas map the presence of copper, while darker or black areas correspond to little or no signal for copper. In figure 48, we have inverted this map so that the darkest areas correspond to the greatest amount of copper, where the underpaint must have been most heavily applied. In this format, the XRF copper map shows a textured quality that calls to mind broad brushstrokes rapidly applied—paint handling that has no counterpart on the final surface. A minute detail may offer further evidence of the haste with which Vermeer brushed out this underpaint. His horizontal brushstrokes—shown in the inverted copper map—must have stopped abruptly at the left edge, splattering blue-black paint onto the buff-colored ground on the tacking margin (fig. 49).45

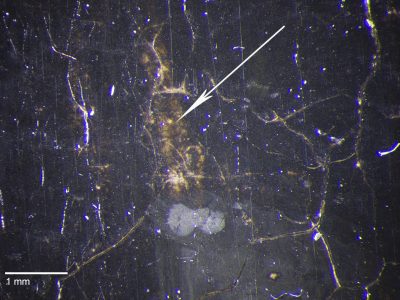

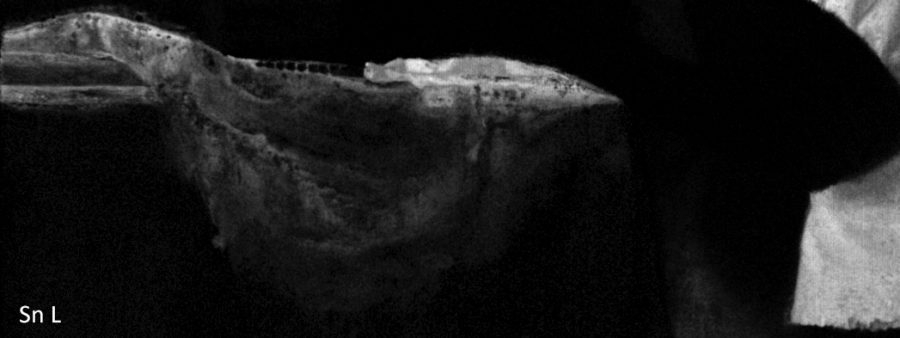

Paint samples from the tablecloth, along with FORS and MS-IRR, as well as magnified examination of the painting’s surface paint, show that Vermeer used similar paints for both the underpaint and final paint of the tablecloth: primarily ultramarine, black, and probably yellow lake. None of these pigments, however, would be a source of the copper seen in the XRF map.46 Instead, it seems that Vermeer added another copper-containing material as a drier to accelerate the curing of his oil paint. The seventeenth-century art lover Sir Theodore Turquet de Mayerne reported that some artists added small amounts of the copper-based pigment verdigris to pigments that otherwise dry slowly in an oil medium.47

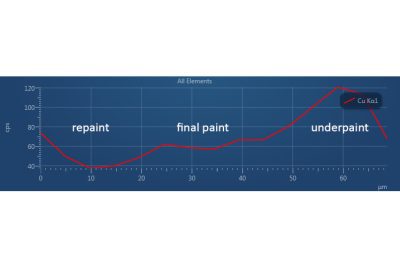

Evidence for such a copper-based drier has been found previously in black areas of Vermeer’s paintings (black pigments being notoriously slow to dry);48 however, the most recent analysis has clarified at which stage of his painting process Vermeer used it and hints at why. The false-color IRR confirms that the area of the tablecloth is rich in black pigment (fig. 50), and in microscopic samples and magnified examination of the painting, there is no evidence of a green-colored underpaint, as has been observed in some other works by Vermeer.49 Microscopic analysis of new paint samples confirms what we inferred from the copper map: that Vermeer used a copper drier more liberally in his underpaint. SEM-EDS analysis of a minute paint sample taken from the tablecloth, a cross section that includes both the surface and underpaint layers, found low levels of copper dispersed throughout the paint (typical of verdigris used as a drier, rather than discrete particles of verdigris pigment). But a line scan for copper across these two layers shows more copper in the underpaint than in the surface paint, evidence that Vermeer deliberately manipulated the properties of his paint at these two different stages (figs. 51, 52 ).50

By adding more drier in the underpaint than in other layers, Vermeer presumably hastened the curing of specific slow-drying pigments so that he could resume work on the painting’s subsequent stages with little delay. This hints at time pressure as a practical motivation, but there also were aesthetic consequences. Vermeer seems to have appreciated—or at least accepted—the brush-furrowed texture in his underpaint. The underpaints based on fast-drying pigments, such as the white lead that dominates the flesh tones, show this rough texture (see figs 30, 37, 39). Adding a drier to the underpaint may have helped to preserve the brush-furrowed texture in paints with slow-drying pigments as well. Conversely, his strategy of adding comparatively little drier to his final paints must have helped him to finish his image slowly, working wet into wet. As he completed each passage, his slow-drying brushstrokes would continue to level, filling in the underpaint’s rough texture.51

Plotting out the Play of Light

In A Lady Writing, a comparison of the final painted image and the preparatory stages (here also revealed by the XRF copper map) shows the essential role of Vermeer’s underpaint in constructing his subtle play of light. In the finished image, light from an unseen window picks out the focal points of the composition—the objects on the table, the woman’s face and her jacket’s yellow sleeve, her Spanish leather chair silhouetted against a lighted wall—while leaving the rest of the space in half-light. Because her form casts a shadow on the chair, the window’s light picks out a single diamond shape on the gold-tooled black leather back and just one of the finials. In time, the viewer might notice a second chair at the left, its diamond pattern barely perceptible in the dim shadows. The only difference between these two chairs appears to be the varied play of light on the wall behind them. Intuitively, we might expect that, in planning this play of light, Vermeer would have prepared the shadowed chair with darker underpaint than its brightly lit counterpart. However, the XRF copper map and magnified examination of the surface show that although Vermeer prepared the chair on the right in the underpaint stage with black, copper-rich underpaint, he seems not to have underpainted the shadowed chair at all, leaving just the brown painted sketch to serve as shadows in the underpaint stage (figs. 53, 54). Magnified examination confirms that in the lighted chair on the right, the painted sketch was followed by both black underpaint and the dark final paint (fig. 55), while in the shadowed chair on the left dark final paint lies directly on the painted sketch (fig. 56).

Vermeer’s mastery in using contrast to direct the viewer’s perception is revealed in the counterintuitive lighting structure—i.e., the darkest underpaint preparing the brightest chair. Although both chairs appear dark in the final image, the shadowed chair at the left was depicted in low contrast against an equally dark, shadowed wall and the chair on the right in high contrast, silhouetted against the lighted wall. The heavily applied black underpaint of the lighted chair creates a densely colored form whose contrast with the white wall amplifies the light.

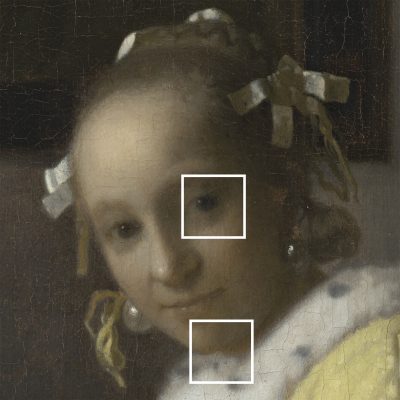

An Improvisational Approach

The XRF copper maps also document Vermeer’s improvisatory development of his compositions. After he completed his underpaint, and before continuing to the final paint stage, he “resketched” possible changes, a practice he shared with Ter Borch.52 Both painters tested out these newly sketched ideas using a different, blackish paint, darker than the initial brown sketch. Ter Borch refined a few forms in this stage and allowed the resketched strokes to play a role in his final image. For Vermeer, resketching seems to have been a more practical tool that he used only as needed to test alternative ideas for his composition. In A Lady Writing, both the false-color IRR and the XRF copper map show quick strokes of dark paint, which presumably include a copper drier, where Vermeer tested an alternate pattern of curls and hair ribbons, including a form that falls against the woman’s cheek. In the final paint, he adjusted the curls and ribbons yet again (figs. 57, 58, 59).53

Vermeer’s improvisations seem to have continued as he revised the composition during the final stage of painting A Lady Writing. Where Vermeer’s peers depicted figures engaged in activities of daily life, Vermeer, with a revision as small as the angle of a quill, engaged the viewer in a moment of absolute stillness. The woman’s pen lies loosely in her hand, forgotten as she turns to meet the viewer’s gaze. But in the underpaint he depicted her actively engaged in writing, a more anecdotal approach that recalls Ter Borch’s earlier composition of a letter writer (fig. 60). The XRF lead map shows that in Vermeer’s first version the woman held her pen almost vertically; the XRF copper map confirms this, showing that in the underpaint the background was brushed up to the margins of the vertical quill, leaving a narrow reserve for the original form. After evaluating the schematic plan for the composition he had laid out in his underpaint, Vermeer shifted the painting’s meaning with his final-stage change of the pen’s position (figs. 61, 62, 63).

Conclusion

The character of Vermeer’s final paint, and indeed the overall tenor of his working practice, is remarkably different from that of his preparatory stages. When he returned to the painting to achieve the final image, he ground his pigments more finely than in his underpaint and was more sparing with the copper drier. In contrast to his vigorous, quickly worked underpaint, the final surface of Vermeer’s paintings reveals a patient, disciplined touch.

In the yellow jacket of A Lady Writing, the texture of the underpaint—broad yellow highlights and deep lines depicting folds in the ochre shadow (see figs. 31, 32) —established a skeletal structure. Over the textured underpaint, Vermeer’s fluid final paint dried slowly, settling to a still surface that scarcely retains the texture of the small, soft brushes he must have used. Vermeer worked with three different pigments—ochre, lead-tin yellow, and transparent yellow lake 54—to create a subtle range of yellow colors: warm brownish shadows, mid-tones modulated from grayish yellow to taupe, and pale, icy highlights. He worked wet into wet without blending, setting discrete touches of one color into another (figs. 64, 65). The remarkable finesse of his final brushwork, a meditation on the play of light, is given structure by the underpaint below.

In Woman Holding a Balance, Vermeer worked slowly as he applied the final paint of the table over the broad brushwork of the underpaint. Painting wet into wet with much smaller brushes, he adjusted his handling to evoke light playing over the surfaces of varied materials (fig. 66). He captured gleaming highlights on pearls and gold chains with unblended dabs of pure white lead or lead-tin yellow. To depict the blurred variations in light dimpling the soft surface of the crumpled tablecloth, he used slower drying paints to his advantage. Here, microscopic examination shows that he set rounded, fluid touches of highlight into the deep-toned shadows while the paint was still wet. As they dried, the two paints leveled to an almost perfectly smooth surface, leaving no trace of the vigorous brushwork below.

The combined evidence of microscopic analysis and chemical imaging builds a new and more detailed picture of the artist at work. Rather than embodying the meticulous fijnschilder approach, Vermeer worked decisively and confidently in the preparatory painting stages of Woman Holding a Balance and A Lady Writing, two works from the middle of his career. Although the underlayers are scarcely apparent today, their contributions to the finished works were essential. In the painted sketch and underpaint, Vermeer’s strong contrasts of light and shade laid out bold, schematic patterns of illumination that he modulated in his final images: preserving the value contrast of a chair silhouetted against a bright wall; using the delicate tonal transitions of interwoven flesh tones to mute a stark patch of highlight on a cheekbone. Similarly, Vermeer laid out his underpaint with bold color contrasts that glimmer through the subtle colors of his final paint: in an underpainted tablecloth, bright yellow highlights against brown shadows pick out the folds of fabric in the half-shadow of the final image, and underlying flesh tones that range from brick red to ivory infuse life into the pale skin of the finished painting.

It was not unusual for painters to handle their underpaint a little more freely than the final paint. Nevertheless, some sources specifically urged painters to smooth the texture of their preparatory layers by sanding or scraping the surface before proceeding to the final painting.55 Examinations of other high-life genre paintings by Vermeer’s contemporaries suggest that a delicate surface called for an underpaint executed with restraint. Van Mieris, the most refined of painters, usually applied his underpaint in thin layers with small strokes that left only a mild impression of the brush.56 Jacob Ochtervelt (1634–1682), in his most meticulous works, filled in the colors of his compositions with a thin, streaky underpaint that had no impact on the smooth final surface of his paintings; by contrast, he painted later works much more broadly, and there he made no effort to control the texture of his hastily brushed out underpaint.57 The texture of Vermeer’s underpaint—coarsely ground pigments, applied in fast-drying, brush-furrowed strokes—was essential to his carefully structured compositions; its forceful texture fills an essential role. His final paint—based on finely ground pigments and applied with soft brushes in fluid strokes that evaded hard contours—might have offered a bland, unvarying surface if he had brushed it onto a smooth underlayer. Instead, the texture of Vermeer’s underpaint offered a “tooth” that secured subsequent paint layers, and the decisive brushstrokes modeled his forms in relief, providing a skeleton that supported the delicate flesh of his final paint surface. Although Vermeer later obscured his freely brushed underpaint almost completely with his final paint, he deliberately left a few gaps in the final paint, allowing the brushmarked underpaint to shimmer along the contours of forms.

The implications of these findings change not only how we think of Vermeer’s working methods but also how we approach the evolution of his style. Elsewhere in this issue, we discuss how, in the final phase of his career, in paintings such as The Lacemaker (ca. 1669–70; Musée du Louvre) or Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid (ca. 1670; National Gallery of Ireland), Vermeer’s work became increasingly schematic as he abstracted his distinctive emphasis on the play of light into a high-contrast pattern in blocks of light and shadow. A clearer understanding of the underlying structure of these earlier genre paintings not only answers questions about his process but also helps us to pose new ones about his artistic trajectory.