This essay uses an eighteenth-century patolu—a fine silk double-ikat textile—as the jumping-off point to explore the complex trading relationship between South Asia and the islands of maritime Southeast Asia. Using the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s data and visualizations, this essay considers the loosening connections between specific localities (including Gujarat, the Coromandel Coast, and Bengal) and their characteristic textiles in South Asia in the early eighteenth century. The commerce in textiles was further transformed by the rise of the opium trade, a commodity for which the Dutch East India Company (VOC) had established a monopoly by the eighteenth century.

A ceremonial patolu textile with a monumental elephant pattern dating to the eighteenth century and still vibrant with red, yellow, blue, black, and white tie-dyed silk, reveals histories of virtuosic double-ikat weaving in Patan, Gujarat, along with stories of the trade routes from Gujarat to the Indonesian archipelago (see the detail in fig. 1).1 A patolu is distinct for its double ikat weave, a time-consuming process that in part determined its value. The Malay term “ikat” means “to tie” or “to bind.” Before the weaving commences for a double-ikat cloth, both the warp and weft threads are tied and bound into bundles in pre-arranged patterns. The bundles of threads are then dyed in a variety of colors, and then the tie-dyed warp threads are arranged on the loom. Once the cloth is woven by passing the weft through the warp, the pattern of a double-ikat textile emerges from the meeting of these tie-dyed warp and weft threads. The visual results are spectacularly vivid, especially when one accounts for the precise planning required to make the cloth.

When considered in the context of the Dutch Textile Trade Project, the patolu cloth here holds value in a different dimension: it demonstrates the contribution of large datasets that have been assembled with their own texture, sensitivity to detail, and an attentiveness to place, materials, and value. The Dutch Textile Trade project allows researchers to visualize a cumulative plot of the Dutch commerce in textiles and also to access the thin, fragile filaments connecting smaller sites. The Dutch Textile Trade Project and the patolu textile reveal a moment in the South Asian textile trade when cloth types were becoming untethered from previous regional specialties and when the Dutch East India Company (VOC) increasingly substituted textiles in their ship holds with the far more addictive commodity of opium.

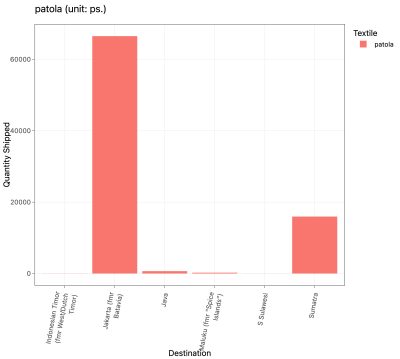

In the case of this patolu textile, found in Sulawesi in present-day Indonesia, the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s tools allow a researcher to toggle between variables that yield more nuanced information. The graph of overall exports of patola (plural of patolu) show that they originated in Gujarat in western India, where the finest of these cloths have been made since ikat-weaving purportedly arrived in Patan in the twelfth century.2 Indeed, the eighteenth century, when the patolu in question was made, represents a late phase in the trade in textiles from Gujarat to the Indonesian archipelago. This centuries-old maritime commerce was initially dominated by Gujarati, Chinese, and Arab traders; then the Portuguese; and then, only in the seventeenth century, the VOC.3 According to the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s data, from 1700–1724 the primary locus of reception for patola was the VOC capital and redistribution site of Batavia (present-day Jakarta), with more than sixty thousand instances of patola recorded as received over the twenty-five year period. Sumatra is the next highest recipient by volume, with around seventeen thousand textiles received in the same period. Sulawesi and Indonesian Timor (formerly West/Dutch Timor) barely register on the graph, having received many fewer cloths directly via Dutch trading vessels (fig. 2).

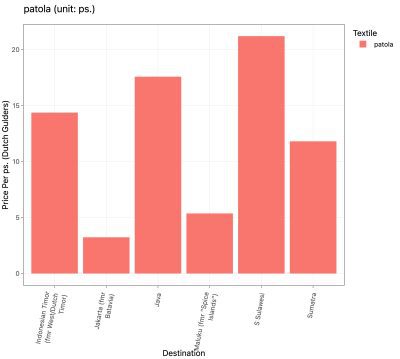

Yet when a researcher shifts the variable in the y-axis from quantity to price-per-piece, an entirely different story emerges, one that accords more closely with what the textiles collected in museums might suggest. By value, the cloths sent to Sulawesi, Java, and Timor are worth more than the others—patola textiles sent to Sulawesi are valued at an average of more than twenty Dutch guilders per piece, over six times the average value of those sent to Batavia/ Jakarta (fig. 3). Even in this period when the Dutch East India Company had solidified a trading monopoly on the supply of South Asian textiles in many parts of the Indonesian archipelago, this data suggests that the preferences and expectations of consumers for stunning textiles prevailed in Sulawesi, Timor, and the smaller eastern Indonesian islands of Roti, Sumba, Flores, Solor, and Lembata, where many patola textiles have been preserved.4 The less expensive patola textiles that lowered the average cost of patola in the records for other locations may have actually been cotton cloths—some from Gujarat and perhaps others from Pulicat on the Coromandel Coast—that replicated patola ikat patterns in the much less costly technique of block printing, or perhaps just had bright, multicolored patterns (fig. 4).5 Some of the remaining examples of these cotton patola bear the VOC stamp (fig. 5).

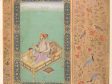

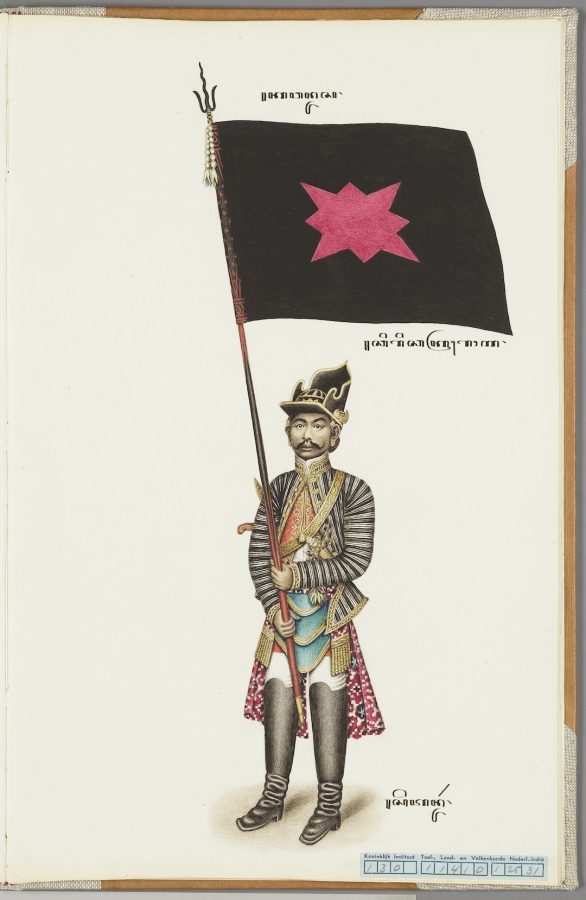

By contrast, the large-scale elephant patolu was probably used as a ceremonial cloth and was retained as an heirloom object, whereas many lengths of patola textiles (both silk and cotton) bore simpler geometric patterns and were used in clothing as shoulder-cloths, sashes, chest-wrappers, trousers, or skirts.6 As shown in nineteenth-century paintings from the royal court of Yogyakarta in central Java, silk patola fabrics were used in the dodot (waist-wrappers) for the sultan’s palace guards (fig. 6).7 The data allow us to ask whether the elephant patolu might be one of the pieces that elevated the value of textiles destined for Sulawesi, a site whose main port of Makassar was an entrepôt for the spice, rice, and textile trade.

The patola trade also diverged from broader trends in the origins of textiles supplied by the Dutch to maritime Southeast Asia, West Asia, Africa, and Europe in this period. At this point in the eighteenth century, the fashion for brightly colored painted cotton textiles had spread globally, reaching middle-class families and European royalty alike. We see evidence of this trade in extant objects, such as a voluminous cape fashioned from indigo-blue and rich red cotton cloth with a swirling floral pattern (fig. 7). These painted cotton textiles also appear in garments worn in marriage portraits made for the Dutch middle class (fig. 8).

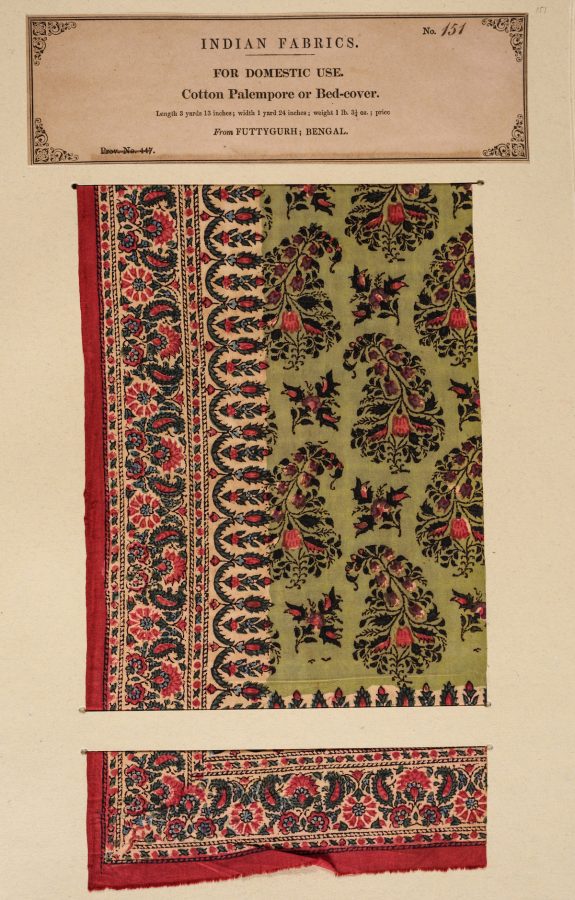

Overall, the last decade of the seventeenth century brought a large-scale shift away from sourcing these kinds of textiles from Gujarat and the Coromandel Coast and toward textiles produced and sent from the eastern regions of Bihar and Bengal. Om Prakash has noted that in 1686, orders from Batavia to sell in the Indonesian archipelago were 93 percent textiles from Coromandel, 4 percent from Gujarat, and 3 percent from Bengal.8 By the 1690s, these figures were in a process of transformation, and the export of cotton textile pieces from Bengal to Batavia doubled in just one year, between 1692 and 1693.9 According to the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s data for the total exports from each region from approximately 1700 to 1724, more than 5.4 million textiles were exported from Bengal and Bihar, in contrast to three million from the Coromandel Coast and fewer than one million from Gujarat.10 The move away from Coromandel Coast textiles has been attributed to upheaval following the wars fought in northern coastal regions between the sultanate of Golconda and the Mughal Empire—an illustration of the fact that not only VOC economic calculations but also the regional political landscape reshaped Dutch strategy in its textile exports from South Asia. At the same time, however, a consolidation occurred based on lower prices and greater availability for cloth from Bengal and Bihar.11 For instance, there is evidence in the shipping records of an increase in the production of kalamkari textiles (hand-painted cotton cloths or “chintz”) from Patna, Bihar (which was often categorized with Bengal in the records), despite the protestations of poor quality that came from Batavia after the cloths arrived.12 That these trends continued into the nineteenth century is suggested by John Forbes Watson’s publication of painted and block-printed textiles that resemble western Indian and Coromandel Coast productions but are recorded as having been made in “Futtygurh, Bengal” (fig. 9).

This realignment in the sourcing of textiles also meant that textile producers in Bengal had begun making cloths for which other regions had long been famous. More broadly, the early eighteenth century in South Asia witnessed a loosening of the connection between a specific locality and its characteristic textiles. Such ties often originated in specific ecological conditions, such as calcium-rich soil for growing fibers and dye plants, alkaline water for dyeing and bleaching, or long-established skill sets of weavers, dyers, and cloth painters. Nevertheless, the data suggest that for the patola textiles, the source stubbornly continued to be Patan, Gujarat, and did not shift to Bengal in this period. The Dutch Textile Trade Project’s data show that similar continuities persisted for other Gujarati textiles, such as the baftas (woven fabrics) that were made with gold threads and were sourced in Bharuch, Gujarat, before being sent to Batavia and the Malabar Coast.

For certain textiles, information in the Dutch Textile Trade Project’s dataset can be challenging to interpret, given the variable names that textiles held or the frequent lack of a descriptor for a textile type in the ship cargo records. For instance, going by the data in the Dutch Textile Project alone, only thirty-seven thousand pieces of “chintz/kalamkari” textiles appear to have been exported from the Coromandel Coast in the period from 1700 to 1724. Although exports from the Coromandel Coast had declined, this number is still surprisingly low. This discrepancy suggests that in the records, some of the kalamkari textiles from the Coromandel Coast were not labeled with their place of origin. Within the raw data, for instance, we find that in the period between 1706 and 1723, 1,630 pieces of rood schitsen (red chintz) were reported to have been re-exported from the Netherlands to Angola, Benin, and Ghana. Although they are not listed as such, these red-dyed textiles may have originated in the Coromandel Coast region.

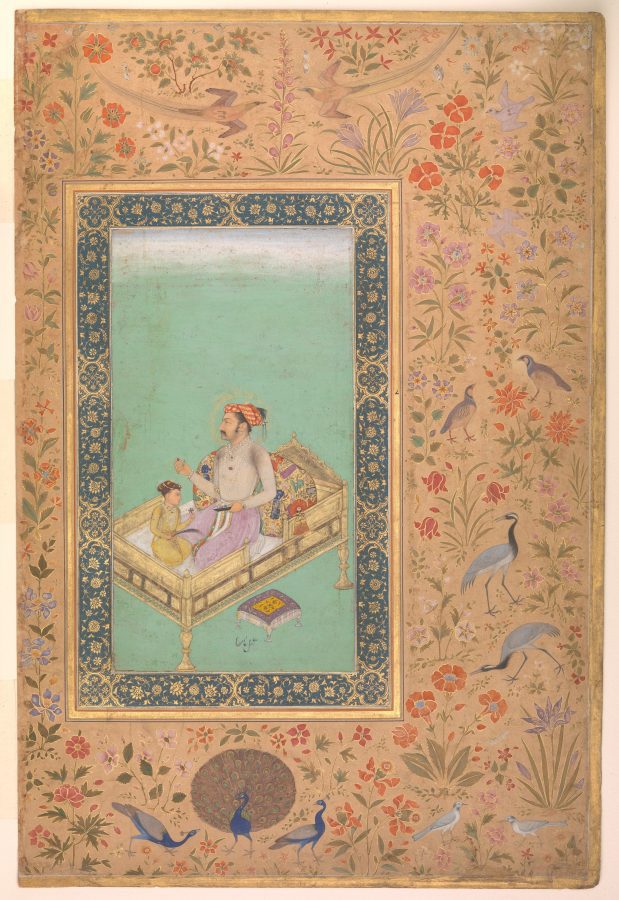

A similar challenge of multiple names makes it difficult to quantify the volume of South Asia’s thin cotton muslin textiles in the Dutch records. The regions around present-day Dhaka, Bangladesh, sourced the finest cotton textiles, which can be seen on men and women in the paintings of the imperial Mughal court in north India and also in Rembrandt van Rijn’s (1606–1669) drawings composed after Mughal works (figs. 10 and 11). The vicinity of Dhaka persisted in being a central source for high-quality, diaphanous white cloth well into the eighteenth century. The Dutch VOC may have shifted away from importing large quantities by the eighteenth century, given broader Dutch trends away from bringing home high-quality textiles due to decreasing profitability.13 Yet fijn (fine) cotton muslin cloth still appears in the Dutch data. Also mentioned is a cloth called caffa, possibly from the Persian word khasa, which was used in South Asia to describe the finest muslin cloths. The caffa textiles from Bengal had gold borders and were sent to Batavia, where they were re-exported to the Maluku Islands, Java, Sumatra, South Sulawesi, and Thailand. Other entries list milmil, from the word malmal, which was the name used for muslin textiles in Bengal. Douriasten and therindains are other names that may have referred to fine cotton cloths. More generally, the multiple names for muslin cloth present an interesting problem from both an analytical and a historiographic standpoint. On the one hand, having many different names for finely woven cotton textiles frustrates efforts to combine analyses of a single type of cloth, since multiple varieties of diaphanous cotton fabric have been sorted in the data as distinctive categories of cloth. Yet this challenge may also reveal a precision in eighteenth-century perceptions of cloth that has been lost today; perhaps these textiles were considered to be entirely different entities because they had varying degrees of fineness, subtle distinctions in texture, or different forms of delicate patterning. Recognizing and respecting these distinctions could align eighteenth-century European records more closely with inventory records and archives from the Mughal and Rajput courts in early modern South Asia, which also contain a profusion of terms for thin cotton cloth—including resonant names such as tansukh (pleasing to the body), Gangajal (water of the River Ganga/Ganges), and shabnam (evening dew).14

These names sometimes carried their place of origin with them, as in the case of the cloth named for the River Ganga/Ganges, along whose banks it had been washed. Despite an overall trend away from specificity of place, not all unique fibers and fashions were decoupled from their origins in the eighteenth-century trade. At the same time that the Dutch VOC and the British East India Company were expanding the production of mulberry (Bombyx mori) silk in Bengal through intensive investment and the establishment of filatures for processing the raw silk, there was a persistence in the production of the wild silks for which Bengal and the northeastern region of Assam had been long been known.15 These silks, which were produced by the eri, muga, and tasar silkworms, among others, were distinctive for their golden-brown and amber colors and the strength of their fibers.16 There were also differences in the processing of the silk. In mulberry silk, for instance, the very thin white filaments are preserved by suffocating the worm inside the cocoon, preventing it from breaking the fibers as it attempts to escape, whereas the wild eri silk moths are either extracted or allowed to eat their way out of the cocoon after metamorphosis so that they survive.17 This makes the eri fibers much shorter, and they are often carded and then spun like wool. In seventeenth-century South Asia, the reigning elite of the Mughal Empire used textiles made from muga wild silk fibers to produce sturdy tent panels (qanat).18 Portuguese merchants in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries collected quilts (colchas) embroidered with tasar and muga silk threads that retained their golden hue.19

In the case of wild silk, the Dutch Textile Project data is more informative in its spreadsheet form than in the graphics, in part because the production of wild silk occurred in much smaller quantities. The wild silk referenced in the documents from which the dataset draws was transported at a volume of only one thousand pounds at a maximum, and it circulated from Bengal (the collecting region for wild silk was from Bengal and Assam) to Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Batavia, and then the Netherlands. These small numbers can be compared, for instance, to the 130,166 pounds of mulberry silk shipped from Bengal to Batavia in 1723 on the ships Risdam, Hopvogel, Ter Horst, Arendsduin, Klarabeek, and Agatha. It is not clear how much of the wild silk originated in each locale, but twelve of the records for wild tasar silk sent from Batavia to the Netherlands had the descriptor “Bengalls” appended to them. There are also records of the textiles allegias, made with tesser (tasar) silk, being sent from Bengal to Ceylon. Like the continuity of high-value patola textiles that originated in Gujarat, references to the wild silk industry within the Dutch archive are evidence that the quality and character of South Asian textiles persisted even in this period of increasing European control and homogenization in the raw silk trade.

While the economic and aesthetic roles of textiles held prominence in the broader VOC trade, focusing on the early eighteenth-century commerce in textiles may belie or obscure the emergence of another commodity from Bengal and Bihar that reshaped Dutch economic prospects in this period: the rise of the opium trade from South Asia to maritime Southeast Asia. By the end of the seventeenth century, the actual proportion of textiles in ships’ cargoes that left Batavia for trade in the Indonesian archipelago had rapidly declined, from 83.52 percent in 1659 to less than half, just 44.62 percent, in 1682.20 As Ruurdje Laarhoven argues, this decline in imported textiles can be attributed in part to the agency of Indonesian textile consumers, who expanded the domestic textile industry within Java to subvert the Dutch monopoly over the trade in cloth.21 Yet this decrease in textiles also occurred at a time when the Dutch were exporting rising quantities of the more compressed and highly addictive commodity of opium.22 Annual consumption of opium in Java and Madura grew from four thousand ponds (the unit of measure, equivalent to 1.09 lbs. or 0.4 kilograms) at the start of the seventeenth century to more than 120,000 ponds by 1717–1718.23 Following its seventeenth-century practices of establishing monopolies over the sale of South Asian textiles in Indonesia, the VOC quickly claimed a monopoly in the opium trade. The Dutch forbade opium only among the spice workers in Maluku and within the enslaved population in Batavia, in order to keep workers productive; otherwise, consumption rose dramatically.24 Opium became the VOC’s most profitable commodity. According to George Bryan Souza, the trade revenue (net revenue or profits) for opium had overtaken that of textiles in Batavia by the eighteenth century; opium accounted for 52 percent of revenue, in comparison to cinnamon (fourteen percent), pepper (twelve percent), and a mere eight percent for all forms of textiles.25

In the study of the eighteenth-century VOC trade, South Asian textiles bring an aesthetic dimension as beautiful, market-specific trade items that helped to spread visual motifs and textile techniques and inspired the production of resist-dyed textiles in Indonesia. If we study textiles in their quantitative dimension, however, we must also confront their role as commodities complicit in cementing VOC monopolies in the spice trade. By the eighteenth century, the trading preeminence of these fragile yet precious cloths was overtaken by the even more ephemeral, consumable commodity of opium, along with its human costs of addiction and loss of life.

The patolu textile that began this essay still reads as evidence for the visible importance of cultural exchange between Gujarat and the islands of maritime Southeast Asia. But it also becomes an emblem of rare continuity in a period of realignment and dislocation: a lasting high-value textile in a period when quantities declined, and more narcotics—and fewer cloths—filled the holds of eastern-bound Dutch ships.