The Zimmern Anamorphosis, an anonymous double portrait of a prominent Swabian jurist and his wife from the 1530s, prompts viewers to hunt for their figures amidst a pictorial narrative and then to recall and mentally recompose its hidden parts. This animated mode of reception guides viewers through a perceptual paradox that integrates a memorable history into its subjects’ bodies. Besides legitimating worldly privileges, this painting demonstrates how anamorphosis supports images’ traditional functions as instruments of memory. Capturing period anxieties about dynastic representation and the precariousness of social status, this painting foregrounds vision’s contingency and anchors immaterial memory in a more durable memorial object.

. . . like perspectives, which rightly gazed upon / show nothing but confusion,

eyed awry / distinguish form.—William Shakespeare, King Richard II

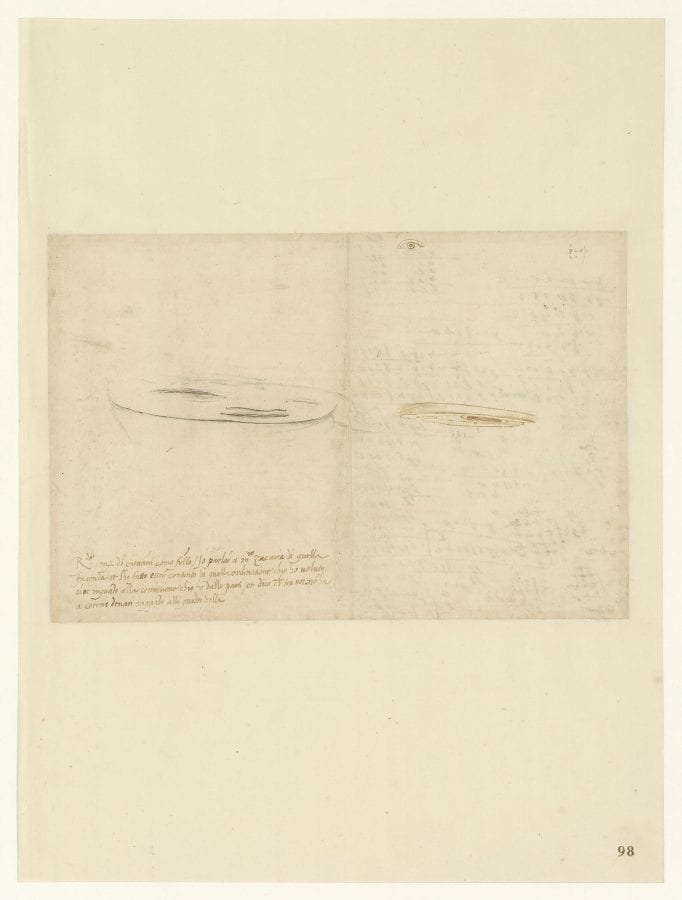

Around the year 1500, Leonardo da Vinci made two small, disproportionately wide sketches of an eye and a child’s head (fig. 1), the earliest known examples of the artistic phenomenon we call anamorphic distortion.1 From a conventional central vantage point, these figures appear misshapen, but they seem naturalistically proportioned when regarded from off to the side with one eye closed. A century later, a character in Shakespeare’s Richard II used the expression “eyed awry” to describe how to overcome the initial “confusion” presented by anamorphic images:2 pictures that the playwright and his contemporaries called “perspectives.”3 Seen from eccentric positions, at oblique angles, anamorphic images appear to reshape themselves, although it is the viewer who enacts their optical transformation.4 Starting with Jurgis Baltruŝaitis in the 1950s, art historians have applied the seventeenth-century neologism anamorphosis (a gerund comprising the Greek words for “again” plus “form”) to images that are designed to be seen from more than one vantage point, as well as to the techniques for making them.5

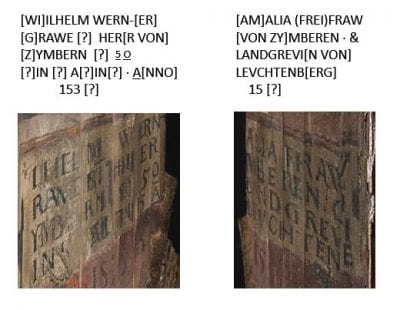

This essay concerns an anonymous, early-sixteenth-century panel painting from southern Germany: the Zimmern Anamorphosis, of circa 1535 (fig. 2), whose pair of portrait subjects—Wilhelm Werner, Count von Zimmern (1485-1575), a university-educated magistrate of the Imperial Chamber Court (Reichskammergericht) at Speyer (fig. 3), and his wife, Amalia Landgravine von Leuchtenberg (ca. 1469-1538) (fig. 4)—appear not merely misshapen when seen from front and center but wholly unrecognizable.6 Like Leonardo’s drawing of a disembodied eye, this painting enlists viewers as active agents of an optical transformation. Its width is similarly exaggerated to about four times its height (excluding the frame), but in contrast to the elongated eye, the painting’s largest figures cannot be recognized at first glance.7 It is the viewer’s task, as Shakespeare implied, to locate a position from which to “eye awry” such a “perspective” in order to “distinguish form.”8 This passage in the play reveals that period viewers were aware that a picture’s effects depended on particular subject-object relations. It also shows that their responses to images concerned how to look, rather than how to make. Moreover, it suggests that they were aware that the normative (“rightly gazed”) viewing mode that entailed a fixed, centered vantage point sometimes had to be exchanged for a more flexible approach. Recent studies of anamorphosis as an early modern mode of representation have emphasized how it challenges the dominant pictorial system for rationalized illusionistic space (i.e. linear perspective) from within that system.9 In contrast, I aim to describe how anamorphosis corresponds with an alternate mode of reception that is rooted in the variability of spatial relations between mobile viewers and mutable images. This essay examines how the viewing process itself amplifies the meanings of one particular painting.

Unlike Leonardo’s two simple figures, which remain entirely visible and identifiable from any vantage point, some portions of the Zimmern Anamorphosis are imperceptible when the panel is regarded from the front and other portions are invisible from its margins. Even more intriguing than the panel’s structure—to be described in greater detail below—which requires viewers to play hide-and-seek with its content, is the way that its masking and revealing complements the painting’s iconography. Just how does the experience of gaining and losing sight of parts of the image produce meaning? I contend that this painting’s idiosyncratic structure prompts viewers to revitalize its content and function as they look. Thus, what makes the Zimmern Anamorphosis so unusual is not simply the fact that the viewer can optically correct the initially confusing, nonmimetic brushstrokes into a pair of portraits by regarding the panel respectively from its left and right margins. More important for our understanding of early modern ways of seeing is how this painting is ideally suited to a mode of reception that engages each observer’s visual reminiscence to mobilize more durable, material forms of memory.

The body of literature on early modern European anamorphosis has grown steadily since Martin Kemp observed nearly thirty years ago that the technique “remained more in the nature of a visual game than a method that could be widely used in normal circumstances.”10 Guided by an exponential increase in primary sources after the year 1600, recent research has understandably concentrated on how anamorphosis signified within the artistic, scientific, and philosophical contexts of the early seventeenth century.11 A concern for many writers is how a phenomenon that challenges the credibility of naturalistic pictorial effects can be a product of the same proportional system that produces those effects. For example, Hanneke Grootenboer has examined how anamorphosis discloses linear perspective’s otherwise invisible mechanisms both literally and allegorically.12 To critique Baltruŝaitis’s assertion that anamorphosis introduces doubt into single-point perspective’s seemingly transcriptive disposition, as well as the art-historical trope of linear perspective as rationalized vision, Lyle Massey has tracked how embodied perception persisted in early modern perspectival theories despite the Cartesian repudiation of sensory data.13 Lately, scholars who draw on psychoanalytic theory and phenomenology are rebalancing our discussion of the artist/object/viewer triad, bringing effects besides intentions into focus.14 New inquiries have usefully redirected attention from “deformed” objects to the “distorted” gaze of the subject in motion.15

Perspectival Paradoxes

The first generation of sixteenth-century anamorphic images—including Leonardo’s drawings—are strikingly similar in subject and format and tend to depict faces. Before the 1580s, when artists began to employ a variety of techniques, figural proportions were typically elongated in one direction. Most familiar to modern viewers may be the large double portrait of courtier Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve, bishop of Lavaur, known as The Ambassadors, by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/98–1543) (fig. 5), of 1533, as the earliest extant use of anamorphosis in a painting designed for an elite social context.16 Notably, Holbein used the novel technique to disguise neither his illustrious sitters nor the measuring, musical, and representational instruments on the double-decker table between them but reserved it for the exposed human cranium that hovers over the patterned marble floor in the lower foreground. At first view, the skull’s proportional logic contrasts with its surroundings, but as one moves farther toward the right, the object’s width seems to contract until, from a particular, unmarked, and relatively elevated vantage point, its form appears as naturalistic as any of the nearby volumetric objects on the table.17 If taken as an allegory of spiritual and worldly epistemologies, the instruments for measuring the world and expressing its fields of knowledge occupy an illusionistic space that facilitates perspicacity. Juxtaposed with this model of human attainment, the symbols for mortality and salvation in the skull and the foreshortened crucifix at the green damask backdrop’s upper left edge require greater perceptual effort.18 Standing paradoxically for both vita transitoria and vita permanens, Holbein’s skull thus represents a synthesis of the ephemeral and the eternal. As an optically unstable memento mori, it alerts viewers to the changeability of (their own) human perception. Eying the image “rightly” produces faulty proportions in a figure that represents something hidden within each and every viewer. To “correct” its proportions requires them to adjust themselves to the image.

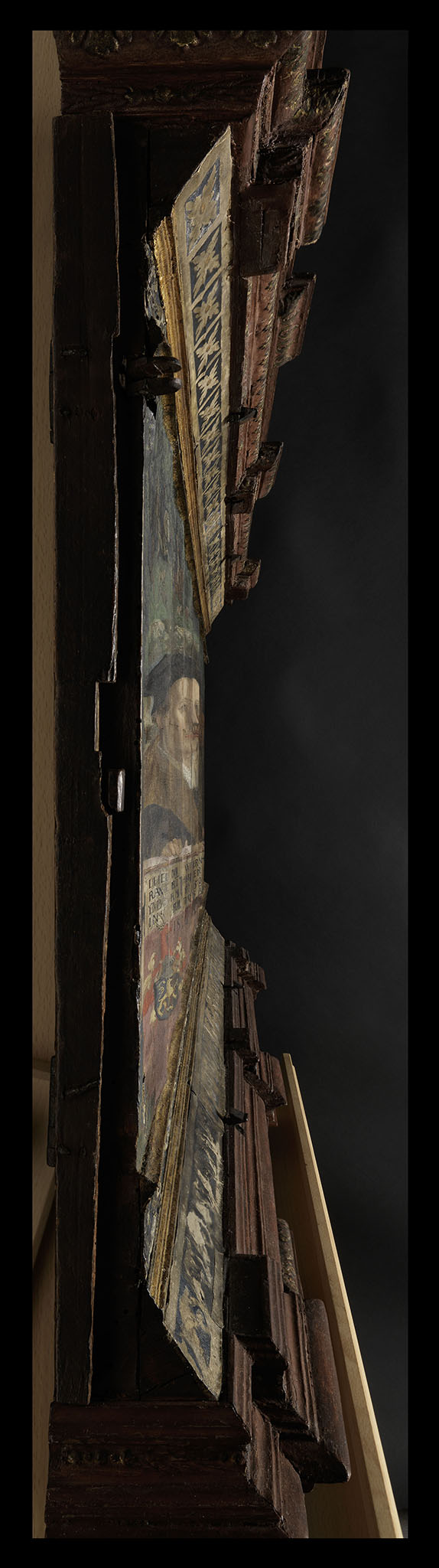

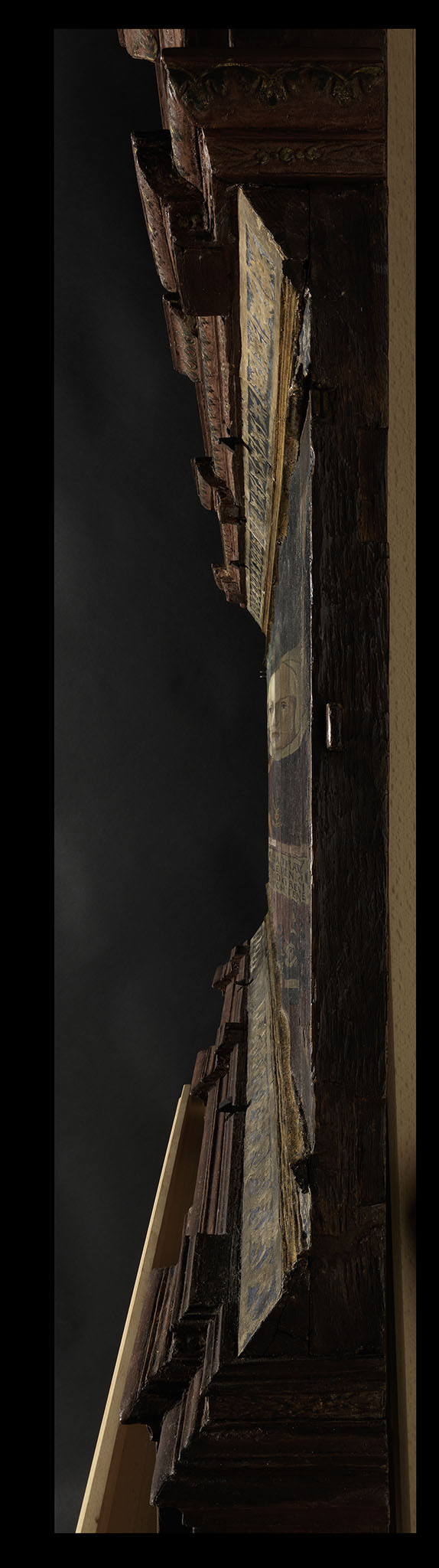

The Zimmern Anamorphosis embodies another type of perspectival paradox that we might call the “imperceptibility of the perceivable.”19 By this I mean that although every stroke of paint on the panel’s oblong surface is fully visible from a central vantage point, much of its surface is devoted to figures that cannot be recognized from that position. Some of its content, however, is comprehensible when seen at close range. Numerous classicizing gilded paper and papier-mâché friezes run side-to-side across its original monumental wooden frame.20 Inset into the frame are six papier-mâché male heads molded as portrait medallions (http://objektkatalog.gnm.de/objekt/WI717), two of which can be traced to extant models in metal.21 A forest setting containing diminutive figures hunting on horseback occupies approximately the upper fifth of the painted panel. Positioned at intervals across the panel’s base are equally small pairs of male and female figures accompanied by coats-of-arms. Interspersed between the members of this abbreviated family tree are fragments of an inscription in black roman characters on an off-white background. Above this lettering, other figurative elements are distributed across the painting’s middle, such as men on horseback, trees, and a tiny gray building in the center, whose tall windows end in pointed arches. These dispersed components constitute a Zimmern family legend, known as the Stromberg Legend for the name of the forest in which it occurs and also as the Legend of the Miraculous Stag.22 Before recounting that legend, I will first outline how this painting functions.

Looking at the Zimmern Anamorphosis

First and foremost a commemorative work of art, the Zimmern Anamorphosis operates on several levels. One of its original functions would have been to integrate its initial viewers—primarily family and guests of the counts of Zimmern—into a collective, dynastic identity. Read literally, the painting’s narrative iconography and semiotic content present that family’s efforts to secure its aristocratic privileges in the 1530s.23 Early viewers would have reactivated the painting’s commemorative purpose and internalized its hortatory messages, which urge viewers to adopt a particular behavioral code demonstrated through positive and negative examples.24 By heeding the implicit warnings in its figural representation of oral legends, viewers would transform them into memorable historical narratives to be passed on to descendants. Perhaps they would also have become more conscious of familial duty.

Standard art-historical questions about who commissioned and executed the painting, as well as its early provenance, may remain unanswered.25 Since its surface has been retouched more than once, the painting remains unattributed. Nor is it listed among the art and furnishings first inventoried in 1623 for the Zimmern heirs, although it may have been noted in 1663 and 1738 at their nearly unoccupied Castle Wildenstein on the Danube.26 Its complexity suggests that multiple hands were involved and its figural scenes are reminiscent of the graphic production of numerous artists active during the second quarter of the sixteenth century in southern Germany.

Despite the lack of external confirmation, we may reasonably posit the painting’s initial functions. Both its manner of presentation and iconography argue for the legitimacy of Zimmern social privileges.27 Together, they reveal the Zimmern Anamorphosis not only as a manifesto of noble identity rooted in specific sites—as denoted by its narrative content—but as an invaluable demonstration of a mode of reception that produces meaning through remembering and re-membering—recalling and re-forming—pictorial effects. Thus, this painting’s significance extends far beyond one family’s self-conception and social relations. As an artifact of visual practices at the time, the Zimmern Anamorphosis provides insight into the processes of visually exploring, finding, and then losing sight of parts of an object before ultimately producing a more complex, inwardly-constituted image than the external pictures that provide its stimulus. It is important to remember that the semantic fields of contemporary words such as the Latin imago and the Middle High German bilde include both immaterial, noetic visual phenomena—mental images—and external, material artistic pictures.28 Accordingly, viewers now as then actively make their own meanings from the Zimmern Anamorphosis by mentally juxtaposing spatially disparate pictorial elements that cannot be seen simultaneously.

A work of art whose form, content, and manner of reception complement each other so thoroughly because of viewer mobility is exciting, because until just recently, art-historical narratives have tended to privilege the ideally immobile mode of reception required by the system of linear perspective. Although this is not always stated, the normative mode of viewing is presumed to be stationary. The mode of reception suited to the Zimmern Anamorphosis, however, utilizes variable viewer emplacement for the sake of embodied spatiotemporal relations with the image as physical object.

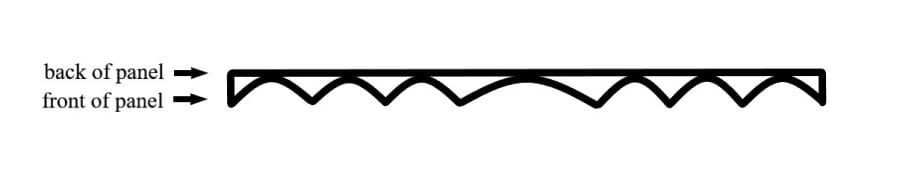

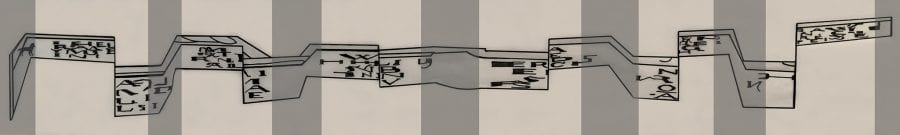

The artist who created the Zimmern Anamorphosis was keenly aware of how spatial relations affect what one sees. Three techniques render the portraits unrecognizable and their inscriptions illegible from the normative vantage point. First, their proportions are exaggerated horizontally; second, the panel is not flat, but formed into a wavelike surface (fig. 6). Six sharp, vertical ridges separate seven concave fields. These centimeter-high ridges are built up with a layer of gesso between the fine canvas and its wooden support. Third, the two portrait subjects are intermingled with each other (fig 7 and video). Each figure breaks off where it abuts the other, except across the center, where the two faces join in one horizontal smear punctuated by the light red line of their lips. The gently undulating surface prevents this smear from being seen from either side. Elsewhere, the transitions are concealed by narrative elements, such as the encounter between two figures in the top center, the riders on the left, and the chapel in the middle. They are also hidden under suggestive, irresolvable forms, such as the flat gray curves on the right. None of these figure into the portraits, nor can they be seen from anywhere but the front. From that position, however, distortion, intermingling, and antirepresentational paint render the portraits unrecognizable. Paradoxically, although we perceive the subjects’ presence in the composition, their particular identities are imperceptible.

Picturing Noble Lineage

Within the painted panel, the way color and shading are used—one could say, the basic artistic grammar of naturalistic representation—does not always align with how we expect objects from the world around us to be depicted. Certainly, some forms, especially the portraits, to which I will return, appear mimetic only from the painting’s outer edges. Other, smaller-scale figures are recognizable at close range and require one to move across the panel to examine the story’s separate sections. This narrative figuration communicates the social ambitions and memorializes the lineage of the lords of Zimmern at a moment in their ascent when their hereditary title of baron was being elevated to that of count.

Along the panel’s lower edge, a row of diminutive male and female figures signifies the importance of parentage. Standing by their coats-of-arms, these men and women represent important marital unions in the Zimmern family tree over four centuries.29 There are six heraldic devices in total. Three represent the arms of the lords of Zimmern: an axe-bearing, rampant golden lion on a dark blue ground. The other three unique escutcheons bear the insignia of their wives. Each of these women represents an advance in social status for her husband’s family.

Starting at far left, the lone woman in a dark blue dress and white wimple stands for Elisabeth von Teck, whom an oral legend characterized as a daughter of a late-eleventh-century duke of Teck.30 The shield to the right of her own black-and-white diamond-patterned coat-of-arms represents her husband, Gottfried the Younger, Lord of Zimmern. His body would have been depicted on the lost left wing, presumably along with more of the iconographic program.31 As a member of the upper nobility, Elisabeth was a major linchpin in the Zimmern argument that their earliest traceable ancestors had been of noble birth. Furthermore, her image underscores an historical territorial link with the sixteenth-century house of Zimmern. For nearly two hundred years, the dukes of Teck had controlled a region of southern Swabia that included the town of Oberndorf, which became part of the Zimmern domain in 1462.32

To the left of center is a couple whose colors have significantly faded. The armor-clad man and the blonde woman represent a mid-fifteenth-century union between the knight, Werner V von Zimmern (ca. 1423-1483) and Anna, Countess von Kirchberg (d. 1478). Her shield bears a full-length crowned female figure raising a helmet in her right hand in gold on a white ground. Represented in the central couple is their son, Johann “Hans I” Werner the Elder (ca. 1455-1495), who joins his right hand with that of his wife, Margarethe, Countess von Öttingen (1458-1528). It was their sons, Johann Werner the Younger (1480-1548), Gottfried Werner (1484-1554), and Wilhelm Werner (1485-1575), who were made imperial counts.33 The placement of Hans I Werner and Margarethe on the central axis signals their closeness to the panel’s main themes. With a maternal lineage extending through the powerful della Scala dynasty of Verona, Margarethe, too, represents a major claim to aristocratic roots.34 These were ancestors she shared with her youngest son’s wife, Amalia, Landgravine von Leuchtenberg, whose underlying presence rounds off the prestige these women personify.35

The single, unattended shield to the right of center would have been reserved for a marriage in the next generation. Lacking both attendant and counterpart, it was surely intended to be matched with another crest once the next head-of-family was ascertained. Placing the then-juvenile eventual successor, Froben Christoph von Zimmern (1519-1566), in this position would have been premature, since in the 1530s, both his father and an elder brother were still living. The presence of this lone escutcheon signifies an anticipated future union.

The Hunt for the Miraculous Stag

Along the painting’s upper edge is a scene populated with figures on the same scale as those in the genealogical pairings below. Against a dark-green, wooded background, several men in sixteenth-century attire gallop on horseback from left to right, accompanied by their hounds. Their target is a large stag leaping toward the right, about two-thirds of the way across the panel. Two more huntsmen ride on ahead of it, unaware that their prey is behind them. The scene recounts a pivotal incident in the Zimmern oral history, which begins with a deer hunt in the woods. The events of so-called Stromberg Legend are set in the early twelfth century, but their oldest extant written source is the Zimmern Chronicle of the 1560s.36 The legend’s protagonist is a Zimmern baron, Albrecht, a son of the Elisabeth von Teck depicted below, who was invited to hunt in the Stromberg Forest, where an extraordinarily large stag was rumored to live. After wandering off from his companions, he was accosted by a mysterious, barefoot stranger dressed in rags, who revealed a forgotten misdeed in Albrecht’s family’s past.37 This encounter is depicted in the center of the forest scene, where a brown horse carrying a man dressed in an early-sixteenth-century coat and wide-brimmed hat rears up before a gray-bearded, bare-headed, and barefoot man in a torn, brown tunic, who approaches from the right. This stranger, whom the Chronicle describes as a “serious and frightening form . . . a human or human form,” a spirit, and a ghost (geist and gespenst), said he was sent by God to reveal something.38 Not depicted is how the messenger led the baron into an unfamiliar castle, where they observed one of Albrecht’s ancestors presiding over a lavish but eerily silent banquet. Once they were outside again, the revenant explained that they had just witnessed Albrecht’s uncle in a state of purgatorial punishment for mistreating his subjects in life. This uncle, Friedrich, and members of his court—including the apparitional guide—had cruelly forced local peasants from their fields and led them to their deaths in a failed crusade. As feudal lord, Friedrich was responsible for protecting his courtiers and commoners alike, who were all slain on this venture. The revenant vanished as Albrecht turned to see the fortress collapse in a sulfurous cloud filled with ghastly wails.39

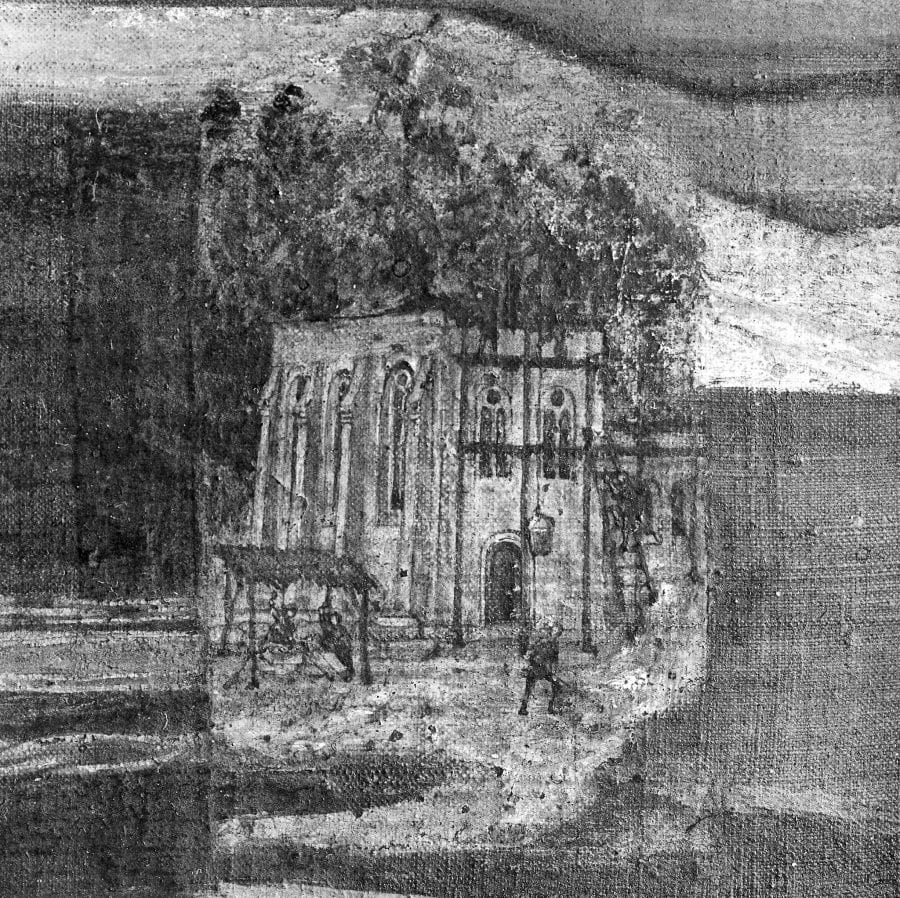

Neither the vision of the silent feast in the evanescent castle nor its horrifying disappearance are depicted in the painting. According to the legend, to make amends on behalf of his ancestor, Albrecht immediately sought permission from his host, whom the chronicler calls Erchinger, Count von Monhaim, to found a nuns’ abbey on the site of the apparition, starting with its chapel, which is depicted at an early stage in the painting’s center (fig. 8). This scene represents the first step in Baron Albrecht’s religious donation to atone for his ancestor’s sin: the future Frauenzimmern convent. In this finely detailed vignette less than two inches high, several stonemasons are occupied on the scaffolding across its facade. Another worker stands in the pebble-scattered yard, and by the buttressed side wall, two stone carvers sit in an open-sided workshop. Several inches to the left, two additional riders look at each other and gesture toward the chapel from separate islands of vegetation. Like the literary topos of a frame narrative, a story within a story, the culminating moment, as the chapel materializes, is visually framed above and to the side by the larger narrative of the hunt gone astray.

In its larger dynastic context, the donation represents more than a conventional display of noble magnanimity and religious piety. It is calculated to align a collective identity with a location. The legendary donation was one means of rooting the Zimmern name in a particular site that was never part of their domain.40 As Franz-Josef Holznagel has pointed out, many place-names in Germany’s southwest corner end in “zimmern,” but few of them had anything to do with the eponymous noble family, beyond its chronicler’s foray into imaginative etymology.41 Instead, the common suffix indicates locations characterized by wooden houses. An unofficial Cistercian women’s convent “at Frauenzimmern” did exist in the Stromberg region from the early thirteenth century through 1442, and its founder, Erkinger, Count von Magenheim, was surely associated with the similarly named nobleman who figures in the Chronicle.42

Although ultimately a piece of fiction, Albrecht’s vicarious act of atonement is made visible in the construction of the building in the center of the Zimmern Anamorphosis. Through this gift to future generations, he would have hoped to repair damage incurred in the past. The potential spiritual value of his uncle Friedrich’s intended mission against non-Christian inhabitants of the biblical lands was nullified by the violent means of enlisting troops. In a simplistic Christian model of feudal social relations, peasants were tasked with laboring and the nobility with raising arms to protect the rest of society, especially their peasants. By exploiting his peasants’ service, Friedrich not only led them to their deaths but also strayed from his own ordained role.

Blind Spots

Such is the extent of the recognizable figuration from a normative vantage point. Most of the panel’s surface is not dedicated to the Stromberg narrative. For example, above the row of genealogical figures is an irregular, off-white plane that shifts at sharp angles as it crosses the panel from side to side. It is covered with wide black roman letters, most of which are individually legible, but the words they spell are not. Closer examination reveals that some characters are not even part of the Latin alphabet, although they use its formal components of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal strokes, including serifs (fig. 9). These pseudoletters’ illegibility may be the viewer’s first visual cue that something is here to be read. First, however, the text that lies askew must be deciphered—an impossible task, since most sections of the inscribed panel contain scarcely more than two adjoining letters between breaks in the script.

Not just (il)legibility (of script) but (un)recognizability (of other forms) are this painting’s themes. Within the larger framework of a family legend, mimetic elements play hide-and-seek and elude recognition, even though from a centered vantage point, viewers can recognize objects that do not figure into the narrative. Perhaps the most arresting of these disconnected signs is a fully formed human eye that seems to float—independent of a face—above the white-haired rider on the left (fig. 10). Tipped up where it might join the bridge of a nose, this eye is less distorted than the one Leonardo drew in his Codex Atlanticus, but its slightly widened proportions suggest that it, too, may be optically corrected—in this, it is doubly appropriate that it is an eye—if it could only be seen from another angle. Yet from the lateral vantage point, from which one might expect to resolve the distortion, this eye cannot be seen at all.

As a representational element, the floating eye is not part of a face whose other features are yet to be discovered. The eye disappears into one of what I call the painting’s “blind spots”: recessed areas that I equate to zones around the periphery of a vehicle, which are hidden from the driver’s view by the vehicle’s own frame. Because the painted panel is not flat, although it may appear so from a central vantage point, looking across the panel from each side reveals only what is painted on the far side of each concave field (fig. 11). Since the anamorphic painted eye gets obscured before it can be optically re-formed, we must conclude that it signifies something other than a ubiquitous gaze. From an oblique angle, viewers are also hidden from it. By calling the viewer’s attention to this fluctuating sign of visibility and disappearance, the eye effectively evokes the relationship between vision and memory: what cannot be seen must be recalled.

Forms above the inscription complicate perception still further. On the right, rising from the lettered plane to the hunt scene above is a sequence of intertwined gray curves thinly outlined in black. At the top, a horse and rider seem to leap over this two-dimensional shape as it bursts into their space. But does it belong to their narrative? Its unmodulated color enhances its flatness and contrasts with its surroundings. If this suggestive but unidentifiable figure contributes nothing to the Stromberg Legend, why does it intrude into the uppermost register? Instead of signifying mimetically, it and the other, seemingly antirepresentational elements—including the nonsensical parts of the inscription—serve other pictorial functions. Their placement within the larger composition cannot be coincidental. They are not there to smooth out perceptual disjunctions but to enhance them.

The floating eye is an index for visual complexity and a sign that stands for sight itself. The hunt topos signifies the viewer’s task. The decoy letters, the elongated yet recognizable eye, and the antirepresentational brushstrokes appear from the front as optically resolvable as the rest. But from no vantage point—neither from the front, nor from the side—do they represent identifiable objects or legible letters; they simply thwart recognition. They play no role in the portraits when those are seen from the marginal vantage points. In fact, from those positions, these areas of the panel cannot be seen at all. Fixating on them while moving to the side does not stop them from vanishing into the blind spots. From the sides, the curved surface fully conceals the floating eye and the intertwined curves, along with the two gesturing hunters, the barefoot revenant, the genealogical couples, and the chapel. Reading the incomprehensible signs or indices in combination with the narrative iconography reveals that an act of looking can be a hunt whose elusive quarry is pictorial stability. When a viewer moves toward the outer margins, even the massive stag escapes into a blind spot.

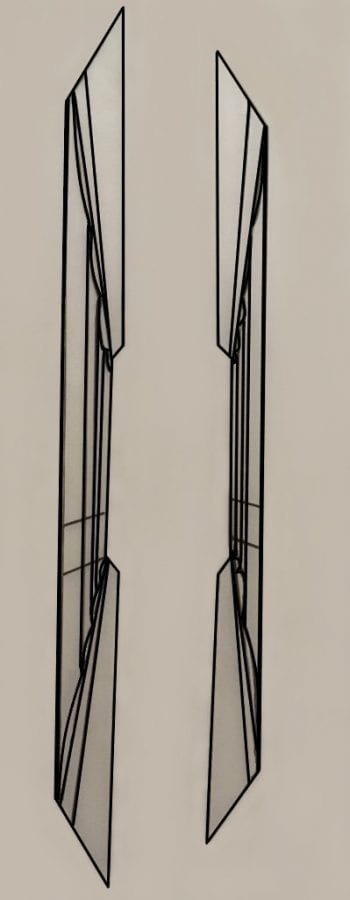

Never in the Same Place at the Same Time

What, then, does a viewer gain by moving to the outer edges and gazing across the picture plane at an extreme, oblique angle? From there, the figural fragments optically shrink and coalesce. In place of one tantalizing, deceptive eye are two eyes, set into a naturalistically proportioned face. In fact, there are two faces, on a much larger scale than the figures in the narrative and genealogical scenes described above. The panel contains two bust-length portraits, but only one may be seen from each side. Additionally, from the sides, the irregular, lettered plane has recomposed—ana-morphed, as it were—itself as a pair of upright, inscribed tablets, upon which the subjects’ names and titles are finally legible despite being abraded. According to the inscription, the likeness on the left is that of Wilhelm Werner, Count (and lord) von Zimmern, age fifty; and on the right, that of Amalia, Baroness von Zimmern and Landgravine von Leuchtenberg (fig. 12).43 Below the inscription are incomplete dates that can be read from each side and two larger shields topped with crest figures: on the left, a bright red stag, and on the right, a black-and-white anthropomorphic head. The large scale and equal size of the two intermingled portraits is significant, even if they appear distorted from the normative vantage point. The expanse across which they are depicted, however, supports the genealogical lineup and the founding myth, which concern all subsequent generations, not just family members who were alive when the painting was new.

The normative frontal aspect foils the primary goal of physiognomic portraiture: recognizability.44 Below the figures, the disjointed alphabetic and alphabetlike characters thwart another means of identification. The titles inscribed under the portraits in the Zimmern Anamorphosis are important to understanding how the painting asserts not just physiognomic identities but also social status. Physiognomy and text are but two facets of how this painting represents its subjects. The two portraits are, despite their size, submerged within the illustrated family legends and heraldic devices. Alternatively, the collective components are embedded in the larger figures of Wilhelm Werner and Amalia. Either way, four hundred years separate the two sixteenth-century faces and the twelfth-century legend, but the heraldic devices anchor a collective, multigenerational identity. Coats-of-arms represent not individuals but noble offices grounded in particular places. The second estate’s investiture of identity in hereditary, immobile property was intended to insure against being forgotten. Acquisition, loss, and recovery are steady themes in their self-representation, as encounters with this painting demonstrate.

The stag hunt provides the premise for a nobleman’s venturing into the woods, a potentially uncharted region where wanderers can get lost. Losing sight of a target and going back to retrieve it is part of how the Zimmern Anamorphosis is experienced. When seen from the side, parts of the forest and some of the hunters and dogs remain visible along the panel’s top, even though this imagery appears pulled out of proportion and vertically elongated. When the faces are “eyed awry,” they become the central focus; it is the hunters above that move into peripheral vision. Arresting the portraits in perfect proportion is an impossible task. A viewer must refocus after the slightest movement—even an involuntary blink.

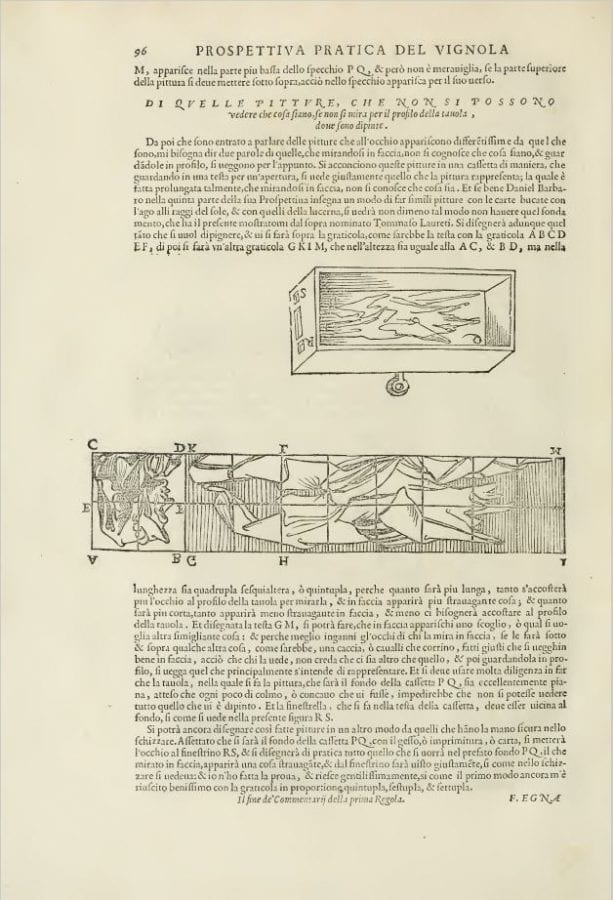

As a type of picture that northern European audiences of that era would have associated in various ways with concepts of “perspective,” the Zimmern Anamorphosis demonstrates how an innovative artistic effect need not depend on simultaneous visibility but could signify meaning through the way in which viewers must perpetually exchange one view for another. This process contradicts the first illustrated instructions for constructing and viewing an anamorphic head in profile on a flat surface, which mathematician and astronomer Egnatio Danti (1536–1586) culled from the writings of architect Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola (1507–1573) and published in 1583.45 Danti cautioned that to enable the ideal lateral gaze across an anamorphic image, the surface to be painted must be perfectly flat, “because any little bump or concavity would prevent one being able to see everything that is painted there” (fig. 13).46 Attributing the construction of partial views to faulty execution, Danti asserted a normative mode of viewing based on comprehensive visibility.47 By assuming that viewers should be able to apprehend an entire pictorial program at once with their physical eyes, he ignored the roles that mental images and visual memory play in perception. He did not consider a different mode of viewing predicated on moving through multiple vantage points to form mental composites of objects that cannot be perceived in their entirety from any one position.

Supporting the tenacity of this latter viewing mode, however, are the partial views and elusive imagery that serve existing uses of images to prompt memory. Here I mean not the ars memorativa (the art of memory)—ancient methods for training the mind to reconfigure received knowledge in order to perform rhetorical feats—but rather memoria as the mental facility to recall what was once perceived and no longer physically present. A picture may guide perception and recall to prompt remembrance.

It would be all too easy to dismiss a mobile visual mode and the pictorial structures it serves as lingering traces of a medieval mindset that was supposedly replaced by “rationalized” sight in the Renaissance, since they do not comply with the stationary, simultaneous mode of viewing required by the system of single-point perspective. We should instead regard this as an alternative visual mode, one that serves as a powerful means of conditioning a frame of mind that we may conceptualize—to use a modern term—as self-perception. This mode of viewing, which recognizes the impossibility of a ubiquitous gaze, draws attention to the contingency of the individual viewer’s subject position. With the Zimmern Anamorphosis, it correlates to the nobility’s fear of dynastic extinction through loss of territories and names.

The painting foils attempts to gather all it offers from the singular frontal vantage point. Yet the very preclusion of those aims allows its content to unfold. As viewers are guided to multiple vantage points, they must piece together momentarily visible imagery with parts of the object that elude their sight. This embodied way of looking involving duration and spatial relations prompts viewers to juxtapose tangible and remembered images. By requiring people to recall what they have seen but no longer have before them—using what psychologists call “episodic” memory, and what Aristotle called “reminiscence”—the Zimmern Anamorphosis confronts the human tendency to forget.48

Transience and Permanence

The theme of forgetting—or more precisely, fear of being forgotten—pertains to one of the painting’s primary functions: to assert aristocratic entitlement. Typical for members of the second estate, from at least the end of the fifteenth century onward, the Zimmern clan—like other fragile noble dynasties—perceived threats to its livelihood and formerly exclusive privileges from multiple angles. First, they were losing professional opportunities to new classes of urban merchants and educated commoners, who gradually assumed the rights and duties, wealth and power, formerly reserved for their social superiors.49 Second, nobles were aware that their place in the social hierarchy and its tangible means of support—land—was precarious. A lack of male heirs could lead to the extinction of a family name entrenched in a particular location—and with it, communal renown, the clan’s memory.50 Moreover, fewer liquid assets to circulate through daughters’ marriages meant social petrification, not mobility.51 Finally, political missteps or misalliances could also precipitate the loss of hereditary territory to clans of equal or higher rank. As part of its hortatory mission, the Chronicle urges preserving hereditary legacies in the face of splintering factions and disputes among the leaders of noble houses, which it portrays as shortsighted measures that imperil these families’ survival.52 Besides offering a tangible means of anchoring the bygone in the here and now—as does any memorial work of art—the unusual structure of the Zimmern Anamorphosis draws attention to the tenuous nature of human memory and the perils of forgetting—first, for the nobility in a late feudal context, and second—and more importantly for the study of early modern images—within the context of that period’s visual paradigms.

Despite its pictorial challenges, this painting is saturated with visual codes that assert not only the aristocratic legitimacy of the counts of Zimmern, through the depictions of episodes in their family history but also their argument for privileged status. On May 24, 1538, Wilhelm Werner and his elder brothers were elevated into the ranks of the upper nobility by Emperor Charles V.53 Their social advancement can be regarded as the final stage in restoring noble privileges to the sons of Hans I Werner von Zimmern, after he had been banished by the Habsburg Emperor Friedrich III in 1487.54 Although we no longer know what deed precipitated Hans I Werner’s fall from imperial favor, he stood on the losing side of a power struggle between two brothers: his immediate employer, Sigmund, archduke of Austria, and the emperor.55 Between 1487 and 1504, the family’s hereditary lands along the Neckar River were reserved in principle for the underaged children, although they were in fact appropriated by neighboring rivals.56 Restoring stability, integrity, and, especially, territorial assets to their family name was a goal to which the young four sons were all dedicated to a greater or lesser degree, even if the eldest did not live to see it fulfilled. At first, they negotiated, then raised arms to get their estates returned.57

This instance of forfeited territories and the subsequent campaign to recover the markers of noble identity can be read as one chapter in the longer story about the tenuous state of traditionally inherited noble privileges in southern Germany. Exclusive land use was a key facet of the feudalist order, and one that had to be continually negotiated and asserted. The redistribution of inheritable lands to competing neighbors follows a regional pattern of splicing and redistributing territories among a small number of minor noble families whose economic and judicial power waxed and waned during the thirteenth through sixteenth centuries. Increasingly, the lower nobility was on the defensive against perceived threats to its hegemony by its (commoner) subjects’ demands and an increasingly educated urban populace who could compete with the sons of nobles for ecclesiastical and court positions.58 The Zimmern elevation occurred a mere thirteen years after the period’s largest peasant revolt (1524/25) was violently suppressed by the nobility and their armies. Less-dispersed domains, such as the duchy of Bavaria, could further strengthen themselves by absorbing neighboring properties. A final pinch was added by the new class of upwardly mobile merchants, who had slowly begun to accumulate privileges, transforming notions of how space could be used and controlled.59

Despite his position as the youngest brother, Wilhelm Werner did more than his share to restore his family’s reputation, albeit in his personal career, rather than as its head. The 1538 social promotion was in no small part a reward for his nearly nine years of service as an imperial assessor (Beisitzer), a position with the duties of a modern judge, at the Imperial Chamber Court.60 To prepare for this career path, his second choice after an ecclesiastical appointment, he had studied canon and civil law at the regional universities of Tübingen (1499-1503) and Freiberg im Breisgau (1503-9), leaving only when his tutor, Georg Northofer, was murdered by another student. Next, he was active for almost two decades at the regional court of the free imperial city of Rottweil on the Neckar, closer to the Zimmern hereditary landholdings around the small town of Meßkirch. The family held ancestral rights to a small number of disconnected territories but had no voice in parliamentary affairs. With two older brothers to lead the family’s public affairs, Wilhelm Werner was free to pursue a juristic career.61

The Zimmern Chronicle describes how the barons of Zimmern convened in 1537 to campaign for the “return” of their rank of count, a title which—as told later by the chronicle writer, who was most likely their nephew, Froben Christoph, Count von Zimmern—they had held unofficially some four hundred years earlier.62 In their campaign for social promotion, the brothers had called attention to their noble habitus, characterized—in the sense given this term by Pierre Bourdieu—by loyal imperial service, deep roots in specific sites, aristocratic wives, and prior territorial autonomy.63 The Chronicle grants Wilhelm Werner special credit for having loyally served the Holy Roman Empire at Rottweil and Speyer.64 Rather than pitching the family’s campaign for privileges as an attempt to gain a new rank, the chronicle writer later attested, they sought official reinstatement for a “lapsed” title. He justified this claim by noting his uncles’ then-current imperial service and a history of marriages with the daughters of higher-ranking nobles.65 “Intermarriage,” reminds Thomas A. Brady, Jr., “is ever a sign of relative social equality and social acceptance.”66 The line of ancestral figures and heraldic devices representing important genealogical connections along the painted panel’s base is a statement of upward mobility via matrimony, as are the larger integrated portrait figures.

Foundational Conventions

The chapel’s central location underscores not only its importance to the noble habitus it signifies, but its placement on the painted panel in the vicinity of the portrait subjects’ hearts may be more than coincidental. Its integration into Wilhelm Werner’s upper torso asserts his familial bond with the convent’s initial aims. Although no dynastic connection between Amalia von Leuchtenberg and the foundation is known, the painted chapel splits the red and golden pendant hanging from her neck. In this respect, its position within the corporeal field of Amalia’s portrait may resonate with the edifice’s designation for the benefit of women.67

The convent chapel is anchored in a particular moment: the initial act of donation. The language used for private gifts to finance new ecclesiastical branches, often expressed as fundatio, or foundation, reveals that location, or ground, is ingrained in such acts of endowment (dotatio). Charters documenting the origins of religious communities customarily list under the heading, “fundatio [et dotatio],” the names of founders, places, religious orders, and governing Church authorities. The spatial importance of a new religious house extends to building costs, whose value may be reckoned as land (fundament) that will become the chapter’s means of support. Deriving from the Latin fundus, “bottom,” the word foundation indicates a supporting surface, base, as well as “a piece of land.” The nascent chapel depicted in the Zimmern Anamorphosis will rise even higher; building its roof would be the next step. In his Etymologies, a medieval source still esteemed in the sixteenth century, Isadore of Seville differentiated the functions of open fields according to the powers that control them. “An ‛estate’ (fundus),” he wrote, “is so called because the family’s patrimony is founded (fundare) and established on it.”68 To successfully create a foundation that will outlast its donor requires not only an immovable place but also commitment to the techniques and media of memory, such as commemorative works of art. Acts of fundant (founding) would customarily be followed by erectant (building), confirmant (confirming), and ornant (furnishing with altars, windows, and pulpits, etc., and adorning with works of art). Images did not always accompany an initial founding act but were often put in place long afterward to commemorate earlier events.

Although the Zimmern Anamorphosis conveys a narrative that leads to the founding of a convent, the purpose of its depiction of the physical structure is not to commemorate that chapter’s origin as an important moment in the spread of Christianity nor to honor an extant (religious) order. For that reason, the painting need not follow the iconographic conventions of the donation genre, which began in manuscript illustrations that accompany textual accounts of chapters’ origins. Paintings and sculptures commemorating the founding of ecclesiastical communities tended to follow standard iconography until the early eighteenth century. Spiritual and worldly donors occasionally appeared alone, but frequently they were depicted kneeling before the Virgin Mary and/or the patron saints to whom their building was dedicated, proffering a miniature version for blessing by heavenly intercessors. Such works of art were not only intended to remind viewers of an order’s local history; they also commemorated acts of founding and architectural intentions, and they provided legal bases for donors’ descendants to assert their prerogatives for regional control. In contrast, Baron Albrecht is not depicted in the same central vignette as the endowed building, nor are any holy figures in sight. The convent built at the culmination of the Stromberg Legend marks the (supposed) Zimmern material investment in a location and in their own noble identity in the guise of a spiritual bequest. More important than its effects for the lives of twelfth-century monastic women is its message that the then-current generation of nobles were conscious of their duty.

Temporality and Memoria

The portrait subjects and the Stromberg narrative are on two different scales, occupy two different levels of reality, and exist in two different time frames, and the painter has made sure that viewers also experience the portraits and the narrative in separate moments. Although comparatively little time elapses during the viewing process as the beholder physically relocates from the center to the margin and back again, it is enough to recognize that duration is part of this mode of reception, as is gathering what one sees at center, left and right. Viewers must be able to connect disparate elements—portraits, heraldic devices, landscape settings, and active figures—and speculate on their relationships.

Here, time is not linear but layered. Underlying the Stromberg narrative conceit is the belief that the soul of the deceased may, on occasion, return to the world of the living. Furthermore, increasingly after the invention of purgatory in the twelfth century and its “triumph” in the thirteenth, the living were responsible for paving their ancestors’ paths out of its fires with prayers, should the deceased have neglected to make their own amends while they lived. Concerning the prevailing mentality that gave rise to many images, Jacques Le Goff proposes that, unlike the human experience of different time frames, in which some events develop over the course of a few hours and others over decades, a contemporary Christian reading of any narrative would have emphasized its eschatological potential. Describing how figures whose earthly lives would never overlap can nonetheless forge relationships, Le Goff declares:

The dead exist only through and for the living. . . [The] living concern themselves with the dead because they will join them in the future. . . The natural and the supernatural, this world and the next, yesterday, today, tomorrow, and eternity are conjoined in a seamless fabric, punctuated by events (birth, death, resurrection), qualitative leaps (conversion), and unforeseen circumstances (miracles).69

The encounter between the ragged, apparitional man and Baron Albrecht represents a miraculous overlap of the living and the dead. The founding of the chapel—regardless of its actual patron—would have been understood as a public gesture to the past, intended to balance a score on behalf of those who had failed to do so while living. Its reputed basis in the year 1134 was to make amends for a sin against the welfare of those more vulnerable in the past, by aiding the spiritual redemption of those presently less fortunate. In contrast, its fictional figurative reconstruction four hundred years later may have offered more tangible benefits to living viewers and their descendants than to their ancestor’s departed soul. Thus, the image of the chapel is at the same time a gesture to a past and, more importantly, a bequest to the future, signaling the family’s efforts to restore its reputation both in the 1530s and four hundred years earlier.

Conclusion

The experience of privileges lost, but also renewed, which motivated the Zimmern barons’ campaign, had a visual component that included the production of paintings.70 The structure of the Zimmern Anamorphosis is ideally situated to make evident the human struggle to hold onto fleeting worldly privileges. The painting performs ephemerality, enacting the impermanence of everything mortal on the bodies of its subjects and its audience. It frustrates viewers’ attempts to view its sitters’ portraits as conventional pendants other than in the mind’s eye. The optical effects employed in the Zimmern Anamorphosis guide viewers to the realization that perpetuating its images happens more perfectly within mental processes than on the picture plane. The question remains as to whether viewers can ever unite all the parts into one coherent whole.

Despite this thematic interest in transience, this painting produces permanence as a conceptual rather than an optical condition, insofar as unstable formats can and do construct political and ideological identities.71 Its subjects continue their painted existence, a form of vita permanens, even when they cannot be identified. The Zimmern Anamorphosis not only asserts its subjects’ social positions, but it also replicates the way visual encounters produce lasting effects. It celebrates a founding myth that combines genealogical and hortatory features. Both elements are entrenched in the production of memory, providing continuity and invigorating events and actors no longer present. In both subject matter and format, this painting problematizes amnesia and loss and enlists the viewer to overcome them. The experimental artistic techniques that render its sitters difficult to recognize interrupt traditional ways of picture making, yet their effects are consistent with traditional uses of images to register memory, to uphold identities, and to offer moral instruction. The integration of form, figuration, and narrative turns oral legends into memorable histories by enlisting viewers to reconfirm individual and collective identities. This use of anamorphosis acts out the task of a memento mori symbol on a larger scale. While the painting may also serve as an epitaph for Amalia, whose death in 1538 may have preceded her likeness, its primary role—as is the integration of her portrait into the painting—is to honor her husband’s lineage.72

The desire to memorialize oneself demands self-awareness, which in turn feeds a sense of superiority, a proclivity the nobility used to legitimize their collective advantages. In a cyclical fashion, collective character defined by social status then motivated the production of artifacts. Through these we may trace the nobility’s self-representational practices, as a group that could afford to control how they were collectively remembered through the writing of chronicles and making of pictorial records: external, material, visual, and textual memory banks.73 Otto Gerhard Oexle identifies remembering as the decisive element that defines the nobility: “Without Memoria there is no ‘nobility’ [Adel] and therefore also no legitimation for noble sovereignty.”74 Remembrance—in an early-sixteenth-century, German equivalent, Gedechtnuß (and its variants, such as the modern Gedächtnis, primarily used today for personal memory)—reminds that the products of memory prompt the living to think on the past, to become conscious of the remaking of the present out of the past.75

Why did the soon-to-be counts of Zimmern choose to align their collective identity with the Stromberg-Frauenzimmern saga, instead of reminding viewers here, for example, of their ongoing investment in the Meßkirch parish church of Saint Martin, another site essential to their identity?76 As a recently renovated urban landmark, however, the latter could still be experienced in person, not only through words and images. Couched as literary and pictorial historiae, chronicles and pictures imply that events of long ago really happened.77 The overlapping time frames in the Zimmern Anamorphosis go even further than the family’s chronicle to produce memoria. Amid the entry for memoria in Petrus Dasypodius’ Latin-German dictionary, of 1535, are the related terms Memoriale as a “sign of remembrance” (ein zeichen von gedenck), and Commemoratio as both a narration and prophecy (Ein erzelung / vorsagung). Rememorio: bringing something into one’s memory again (Ich bring wider in gedechtnuß) is aligned with finding something familiar that had been set aside, perhaps momentarily forgotten.78 Memory is charged with bringing the forgotten back to mind. In the Zimmern Anamorphosis, memoria is performed in the Memoriale signified by the chapel, in the Commemoratio of the Stromberg Legend and unattended shield that awaits the next generation, and as Rememorio in the mobile manner in which the painting as a tangible object must be approached. It requires the viewer to look again from another position and to recall what has already been seen, retrieving embodied experiences into the present moment. Past, present, and future are intermingled in memory’s semantic field, as they are in the Zimmern Anamorphosis and how it is perceived. The artistic interleaving of figures and events that would be separated by temporal rifts, when arranged along a timeline, suggests how deeply they affect one and other.

Substantiating period perceptions of time as layered or enfolded in De docta ignorantia (On learned ignorance), of 1440, Nicholas of Cusa asserted that past, present, and future may be ultimately unified. Although Nicholas intended this seminal text, in which he introduced his concept of the unity of opposites (coincidentia oppositorum), to argue for theological paradoxes, one might nonetheless cautiously apply Nicholas’s words to secular matters of the early modern era. Describing God’s capacity to enfold temporality, Nicholas wrote:

The present, or the now, enfolds time. The past was the present, and the future will become the present. Therefore, nothing except an ordered present is found in time. Hence, the past and the future are the unfolding of the present. The present is the enfolding of all present times; and the present times are the unfolding, serially, of the present; and in the present times only the present is found.79

Can we find temporal distance reconciled in the here and now not only in memorials motivated by predominantly religious objectives but also in commemorative objects that foreground worldly content and serve secular ends? Replacing a linear model of time with a layered one permits perceiving otherwise disparate events through each other.

Yet, the finite mortal eye must perceive disparate components serially; as humans, we can only collapse the series into one enfolded moment in our minds. To “eye awry” an image, we move from center to sidelines, from near to far, and back and forth. Oscillation between different vantage points leads not only to reckoning with the contingent nature of sight but also to comparing multiple subject positions. Images that appear to change before the eyes prompt viewers to assimilate what is temporally apart: the distant past in the historical imagery, which includes the once-present portrait subjects who have now become figures of the past, the former-future in the single coat-of-arms that projects the clan’s survival, and the ever-changing present experienced by the viewer.

It would be difficult to overestimate the significance of the concept of historia memorabilis (memorable history) with respect to the content, format, and functions of the Zimmern Anamorphosis. It functions differently than a conventional Memorietafel, a commemorative religious painting before which the faithful are asked to recite prayers on behalf of its donor’s soul. In the latter, a patron may position his or her likeness to perpetually perform acts of devotion. Like a Memorietafel, however, the Zimmern Anamorphosis enlists viewers to complete a task on behalf of its patron(s), albeit not in a religious setting. Instead of performing piety, the painting dramatizes the dichotomy of the fleeting and the enduring by mobilizing viewers to complete its messages. For viewers outside the family, it may incite awareness of how reactivating a perishable identity—in this case, someone else’s—can also produce reflexive states.