Considered within the context of his biography, his overall artistic production, and the seventeenth-century Dutch market for tronies, a recent multidisciplinary investigation of Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with the Red Hat (National Gallery of Art, Washington) suggests that this small painting represents a pivotal moment in the artist’s career. Vermeer experimented here with bolder, more abstract brushwork and more highly contrasting pigments—an approach that grew out of his handling of the preparatory stages of the painting process and that he ultimately adopted in his high-life genre works as well. Positing the painting as an experimental foray that presaged Vermeer’s subsequent development also indicates a likely date of about 1669. For further exploration, see “Methodology & Resources,” “First Steps in Vermeer’s Creative Process,” and “Vermeer’s Studio and Girl with a Flute” in this issue.

Introduction

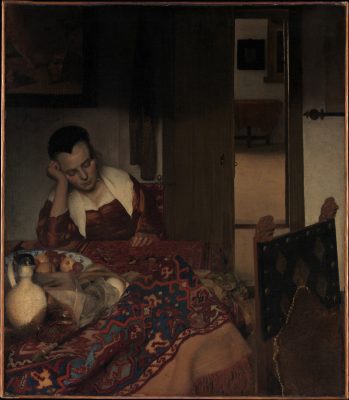

When the Delft collector Pieter van Ruijven—often described as Vermeer’s principal patron—died in 1674, his collection included twenty-one of the artist’s paintings. They were inherited by Van Ruijven’s daughter Magdalena and, upon her death, by her husband, Jacob Dissius. The 1696 inventory of Dissius’s estate and property contains a list of paintings: item number thirty-eight on the list was “a tronie in antique dress, uncommonly artful.” Following it, “another ditto Vermeer”; and after that, “a pendant of the same.”1 One of these paintings is likely to be the National Gallery of Art’s Girl with the Red Hat (fig. 1).

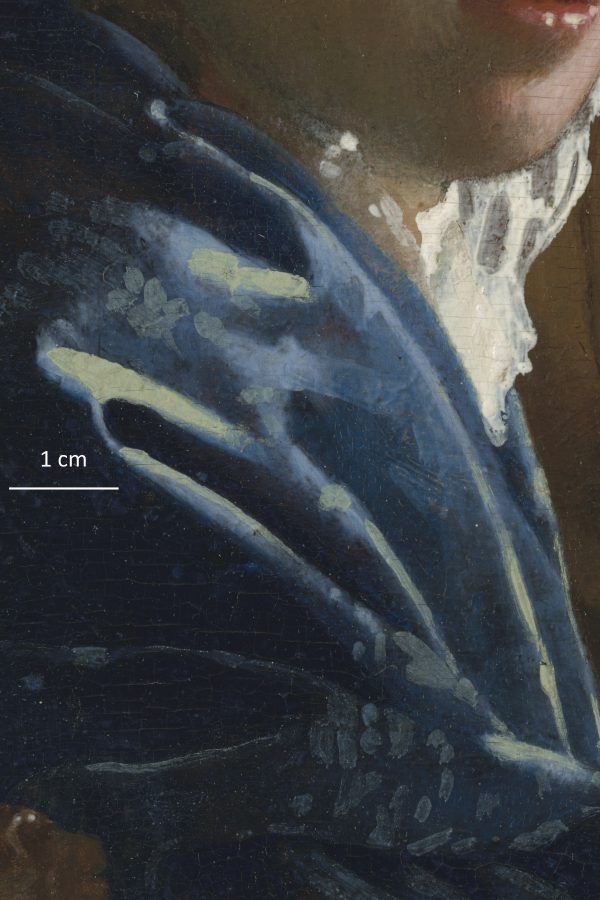

The composition depicts a young woman staring out at the viewer from beneath a broad, feathery, cherry-red beret. Dressed in a lush blue robe with hints of patterning, the woman seems to radiate energy—a feeling that stems as much from the vibrant color combinations as from the fixity of her gaze. The painting is intimate, immediate, and daring in both its conception and execution. Our recent in-depth study, which compared and contrasted in detail the materials and sequential build-up of paint layers in all four of the paintings by and attributed to Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, further illuminates how Vermeer achieved the visual qualities that distinguish Girl with the Red Hat from his more formal genre works, such as Woman Holding a Balance (fig. 2) and A Lady Writing (fig. 3).

Considered within the context of Vermeer’s biography, his overall artistic production, and the seventeenth-century Dutch market for informal head studies (tronies), the new evidence we have gathered on his working process suggests that Girl with the Red Hat, as perhaps the only accepted tronie by Vermeer executed on a wood panel support, may have functioned as a kind of trial balloon for his subsequent artistic development. Every aspect of this diminutive painting suggests openness to experimentation: the support is a reused panel; the paint handling is unusually free; and the compositional format seems to merge tronie and narrative genre. Positing the painting as an experimental foray impacts its current dating of about 1666/1667 and its place within Vermeer’s oeuvre, and it may explain the painting’s uncharacteristic support. This paper explores the how, why, and what next for Girl with the Red Hat.

Part 1: Tronies in Context

Best known for meticulously crafted high-life genre paintings like Woman Holding a Balance and A Lady Writing, Vermeer was part of a large network of elite artists producing idealized images of daily life for the highest levels of the Dutch art market in the third quarter of the seventeenth century. Of Vermeer’s small oeuvre of thirty-five widely accepted works, twenty-five portray cosmopolitan women and men at leisure in well-appointed domestic interiors.

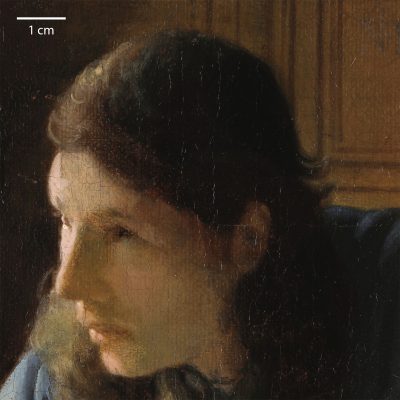

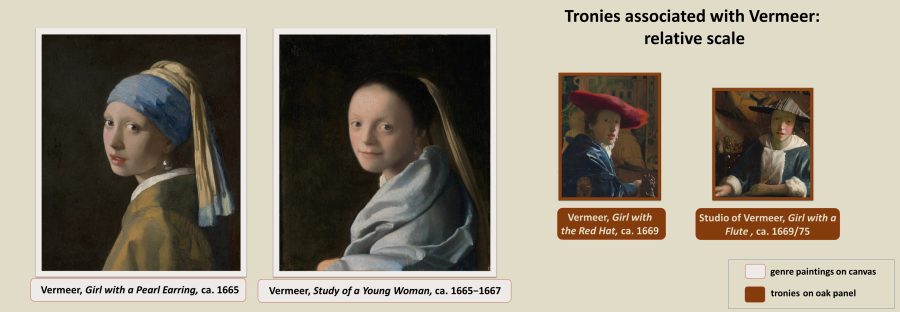

Vermeer executed other subjects as well. His surviving works include a handful of history paintings, landscapes, and, of most interest for the present study, three bust-length paintings of imaginary figures, or tronies: the National Gallery’s Girl with the Red Hat, Girl with a Pearl Earring in the collection of the Mauritshuis in The Hague, and Study of a Young Woman at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Another related work at the National Gallery, Girl with a Flute (see fig. 67), was long considered a work at least partly by Vermeer, but our recent study has compelled a reconsideration of this attribution—which is the subject of an article appearing elsewhere in this issue.2 Nonetheless, features that Girl with a Flute shares with Girl with the Red Hat make it relevant to our discussion, as it suggests there existed a type of small-format tronie associated with Vermeer and his orbit (fig. 4).

Defining Tronies

A vaguely defined category of artistic production in the early modern period, the term “tronie” is generally understood to describe informal representations of faces, which might include head studies quickly painted from life; images of generic “types” such as peasants, fools, the elderly, or children; people in costume; or idealized images of mythological and historical heroes.3 Beyond that, it is difficult to pinpoint exactly what the term tronie meant during the period. It was not a genre articulated in theoretical writing, but rather a seemingly catch-all term commonly used in inventories and other documents to denote a head- or bust-length image of an unidentified individual. Although not an “official” genre, most tronies followed the same general format: figures were depicted at head- or bust length, set against a plain (usually dark) backdrop, and frequently executed on small wood panels with a rapid shorthand that exposed the painting process. While likely modeled on actual people, most were not intended as portraits but as deliberately anonymized studies of expression, type, and physiognomy. Rather than portraying an individual, such tronies explore how a person is portrayed, describing light and shadow on human skin or what a face looks like when seen from a particular angle. They capture expressions, convey textures, and imagine characters through the inclusion of fantastic costumes and accessories. Many considered the execution of tronies integral to a young artist’s training, as they encouraged careful attention to composition, character, and physiognomy.

In the northern European tradition, tronies played an important role as preliminary studies for larger works from the mid-sixteenth century onward. Their popularity increased from the late 1620s until about 1660, especially among artists working in Antwerp, Haarlem, Amsterdam, Leiden, and Dordrecht.4 For Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), tronies were not independent works of art (though they came to be highly valued as such) but rather fresh and vivid working documents that remained in the studio to aid in the realization of his many commissions. The inherent informality of the genre often encouraged technical and artistic experimentation, and tronies reliably ascribed to an artist can vary considerably in style and technique from that artist’s more formal oeuvre. For example, Frans Hals (1582–1666) and artists in his circle painted tronies that exploit the characteristically vivid quality of their brushwork with a loose, open touch that contrasts with their more highly finished portraits and on occasion anticipate a subsequent transformation in their painterly style.5

Jan Lievens (1607–1674), Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), and artists working in their ambit also created dynamic works that explore human physiognomy, expression, and dramatic lighting effects. The audacity of experimentation is especially evident in youthful works by Rembrandt and by the artists he trained. Rembrandt’s early Amsterdam portraits are typically brought to a high level of finish, but his small tronie panels are much less formal. In the dramatically shadowed self-portrait tronie from around 1628, for example (figs. 5, 6), he manipulated his paint aggressively with a touch that varied from almost featureless brown in the darkened forehead and eyes to thick dabs of pink and tan on the lighted side of the face. He asserted his command of the medium by leaving the brown painted sketch exposed in the shadows and scratching through the wet paint to define his unruly curls.

While theorists like Karel van Mander (1548–1606) denounced tronies (and portraits, for that matter) as “but an adjunct of history painting and when practiced on its own . . . a sign of laziness or the choice of a road to easy money,” tronies, whether created as standalone works or as practice pieces, soon found their way to the art market.6 In part, selling tronies created in the master’s atelier or independently was a good way for young artists to begin to carve out an identity in the market with small, inexpensively priced works.

Vermeer and Tronies

Vermeer began his career in the mid-1650s as a history painter and may well have executed tronies as part of his training or in preparation for that noble work. In addition to the three tronies listed in the Dissius estate inventory, the sculptor Jean Larson,7 active in The Hague, owned “een tronie van Vermeer” at the time of his death in 1664—a work subsequently described as “een principael van Vander Meer.”8 And while the history paintings Vermeer made in his early years (Diana and Her Companions, ca. 1653–54, Mauritshuis, The Hague; Christ in the House of Mary and Martha, 1655, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh) lack the sort of overtly expressive figures for which tronies were typically prepared, tronies also offered an ideal platform for studying subtle or complex interplays of light and shadow—a concern that preoccupied him throughout his career.

The 1676 inventory of Vermeer’s widow, Catharina van Bolnes, includes several tronies from his own paintings collection: two by “Fabritius” (presumably Carel Fabritius [1622–1654]), which hung in the most important room of the home, the groote sael (great hall) and in the binnekeuken (inner kitchen), a space that typically functioned as a family’s main living space; two by “Hoogstraten” (presumably Samuel van Hoogstraten [1627–1678]); and two described as “op sijn Turx” or “in Turkish clothing” (“Turkish” often being used generically at that time to mean “foreign”). One further unattributed tronie hung in the aghtercamer (back room) upstairs. Possibly also relevant in this context, in the voorkamer (anteroom; probably Vermeer’s studio) the inventory lists, in addition to canvases, “6 paneelen,” unpainted panels that Vermeer may have intended for more tronies similar to Girl with the Red Hat.9 It is possible that one or more of the unattributed tronies may have been by Vermeer himself, and it is intriguing to consider whether his conceptual understanding of the genre might have been influenced by the work of two artists of the Rembrandt school that were on display in his home (a possibility to which we will return below).

Although tronies account for a small portion of Vermeer’s known surviving output, they are today among his most beloved works. Girl with a Pearl Earring has become virtually synonymous with his name; her expectant gaze and parted lips, ahistorical garments, and magnetic blend of charm and reserve have endowed her with Mona Lisa-like status (fig. 7). Girl with the Red Hat, meanwhile, is one of the National Gallery’s marquee paintings, gracing the cover of its most recent edition of Master Paintings from the Collection and meriting a stop on public tours of popular collection highlights.10 The enduring appeal of these works may derive from their very tronie-ness. Like Vermeer’s genre paintings, the tronies show women who are serenely calm and arrested in a moment in time, but in eschewing a time- or location-specific narrative they become more immediately accessible to modern audiences.

For example, the eponymous subject of Girl with a Pearl Earring gazes over her shoulder at the viewer from beneath a headscarf contrived of vividly colored blue and yellow fabrics. Seen before a dark background, her face bathed in light, she seems to emerge from a void. Without the distraction of narrative accessories such as a letter, attendant, or even recognizable contemporary costume elements, the viewer can focus on the woman’s captivating gaze and the artist’s sophisticated manipulation of light and darkness. Rather than limiting our imagination by rendering something recognizable and known, this artfully draped head covering, apparently of Vermeer’s own invention, invites speculation. Is the woman a figure from history? Or possibly from a distant land? Similarly, in Study of a Young Woman, Vermeer pictures a young woman with a pearl earring and a yellow headscarf looking over her shoulder at the viewer (fig. 8). Her figure is obscured by a silvery blue wrap whose folds suggest a heavy fabric, perhaps satin, with glints and gleams that insinuate a pattern. Silhouetted against a seemingly flat, dark background, with a bright light illuminating her face, she too appears timeless, universal, a mesmerizing study in expression and the articulation of light and shadow.

Girl with the Red Hat and even Girl with a Flute share many of these qualities. There is no true sense of physical context in these paintings, even though their subjects are situated within spaces loosely defined through the inclusion of lion’s-head finial chairs in the foreground and hanging tapestries beyond.11 The woman’s blue cloak in Girl with the Red Hat recalls the one in Study of a Young Woman but appears to be made of heavier fabric. And while its pattern is more clearly articulated, it is still so abstractly rendered as to be merely suggestive of an expensive garment—perhaps recalling, as Walter Liedtke suggested, the caffa or damask that Vermeer’s father made in his early career.12 As in all of Vermeer’s tronies, the costume resembles an artful arrangement of random fabrics, not actual apparel. The white scarf comes up so unusually high on her neck that it is surely an artistic creation, while the feathery red beret has no known parallel in seventeenth-century fashion and seems to be Vermeer’s own improvisation.13 This unusual and evocatively “historical” head covering becomes a vehicle for the artist’s exploration into the interplay of light and shade—the shadows cast by the hat’s broad brim; the way the light glistens off the woman’s moistened lips.

Girl with the Red Hat: An Outlier

Despite the many resonances with Vermeer’s two other known tronies, Girl with the Red Hat remains an outlier in his oeuvre. Measuring just twenty-three by eighteen centimeters, it is his smallest extant painting and the only accepted work executed on an oak panel.14 Certain structural and conceptual features—size, support, the presence of a fully articulated background, and the highly imaginative head covering—are shared with Girl with a Flute, which has led numerous scholars to consider the two as pendants and to consider their authenticity in tandem. However, by the time we undertook this research there was no longer any question that Girl with the Red Hat is indeed by Vermeer, whereas Girl with a Flute was still only “attributed to” Vermeer.15 The suggestion that the works were intended as a pair is premised on their visual similarities but also on the assumption that they were the only two tronies by Vermeer of this size and compositional arrangement.16 However, while it is true that they are the only surviving small tronies on panel with tapestried backgrounds, we know that more tronies existed (for example, the one owned by Larson), and given the presence of several wood panels in Vermeer’s studio at his death, it is not too far a reach to imagine he may have produced (or had plans for) others in this format.

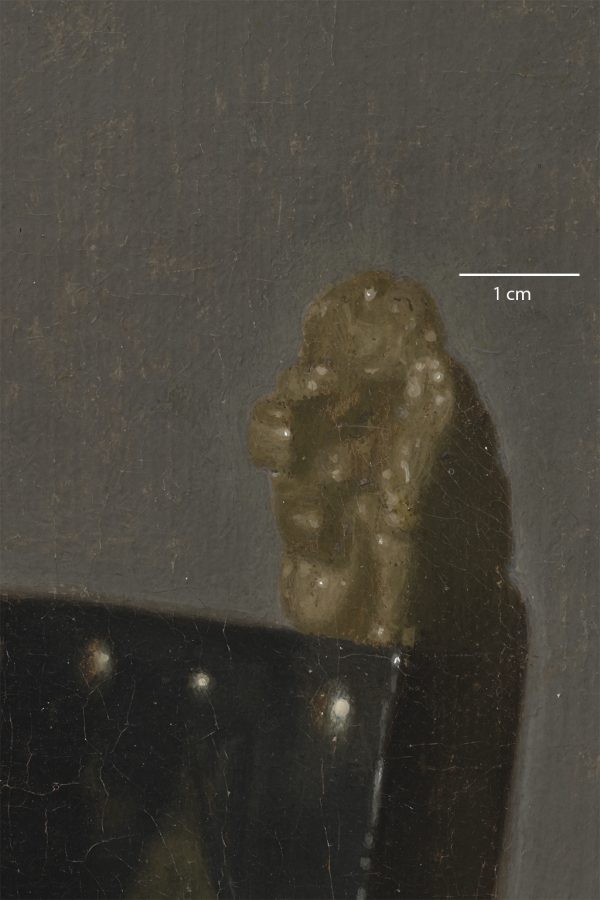

In no other tronie (or high-life genre painting, for that matter) is Vermeer’s artistic expression so informal, or his palette so vibrant, as in Girl with the Red Hat. And in no other tronie does he engage the viewer so directly. While the woman’s bright eyes and parted lips lure us in in a manner analogous to Girl with a Pearl Earring or Study of a Young Woman, the sensation of intimacy and expectancy is heightened. Vermeer masterfully achieved this effect by having the woman lean her arm on the back of a chair in the immediate foreground. This chair has long puzzled scholars, who, under the assumption that it belongs to the seated woman, have complained that the lion’s-head finials are too close together, incorrectly aligned, and, more critically, that they face out when they ought to face toward her. Refusing to accept that Vermeer would ever make such “mistakes,” some have used this as grounds to doubt the painting’s authenticity.17 However, there is a simple explanation for the orientation of the finials. On these chairs, which frequently appear in Vermeer’s works, the lion’s-head finials face forward, toward the seat. The most convincing explanation is that the chair faces out of the picture space; its seat, out of view below the frame, would extend into the viewer’s space. The repoussoir on which the woman leans is the back of the viewer’s chair—a crucial component of the artist’s strategy to capture our attention and draw us into the scene. Although Vermeer most frequently depicted an empty chair seen from the back, which serves as a repoussoir that distances the viewer from the scene, he had shown a chair turned toward the viewer in one earlier work, A Maid Asleep at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (fig. 9). In that work, the dozing woman and indistinct shape on the empty chair (perhaps a visitor’s cloak?) suggest an intimate scene. In Girl with the Red Hat, Vermeer brings the viewer into that intimacy. While most of Vermeer’s women invite contemplation and distanced admiration, the figure in Girl with the Red Hat leans forward to speak to us, demanding our complete engagement.

Part 2: Vermeer’s Painting Process

Through focused study of the four paintings at the National Gallery by and attributed to Vermeer, we have gained a clearer sense of how Vermeer created the distinctive visual qualities of his paintings, especially the techniques he employed to distinguish Girl with the Red Hat from his high-life genre works. Our study not only offers a new framework through which to consider the evolution of Vermeer’s technique but has also prompted questions about the role of tronies generally, and Girl with the Red Hat in particular, within his oeuvre.

The research methods discussed in this study offer two avenues of approach: analysis both at specific points (including sampling and non-sampling methods) on the paintings and across entire paintings. This is a brief overview of our methods; full details are found in the appendix. Further information can be found by clicking on the figures, which illustrate the main techniques used in this paper.

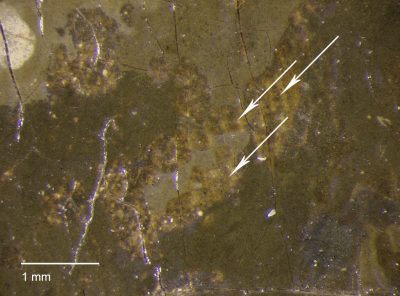

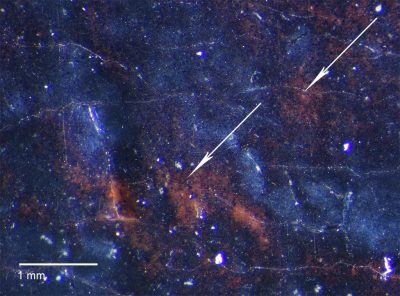

We gathered detailed information at specific points through microscopic analysis of a few paint samples: polarizing light microscopy (PLM) identified individual pigment particles in a few grains of paint collected from the paint surface; light microscopy of paint cross sections showed the layer structure; and analyzing those samples using scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) gave information on the pigments in each layer. It was also possible to infer pigment mixtures at specific points without taking samples using X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF)—which, like EDS, identifies chemical elements present—and reflectance spectroscopy collected with a fiber-optic probe (FORS), which gives information on electronic transitions and molecular structure from which color values can be determined.

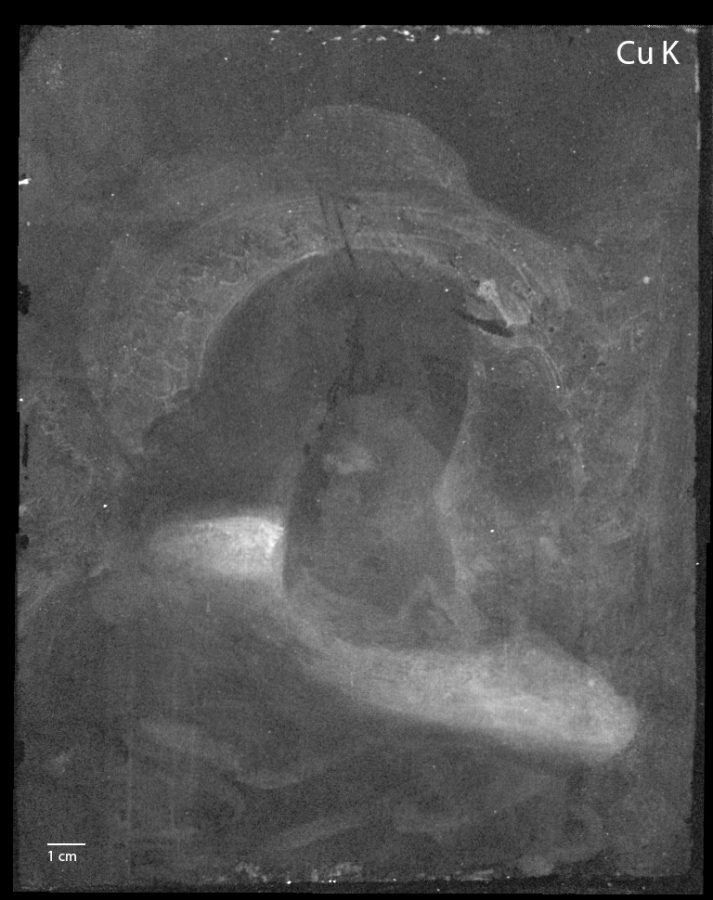

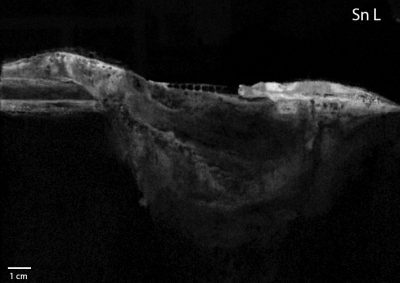

Chemical imaging performed across entire paintings offers a powerful way to visualize the distribution of painting materials, which can reveal aspects of Vermeer’s paint handling for specific parts of the composition. We inferred where pigments were used throughout each painting based on chemical elements detected with X-ray fluorescence imaging spectroscopy (XRF element mapping) (fig. 10), or identified pigments based on electronic transitions and molecular structure information obtained with reflectance imaging spectroscopy (RIS). In multispectral infrared reflectography (MS-IRR), three infrared images are combined in a false-color infrared reflectogram (IRR) (fig. 11) that separates pigments more clearly than is possible with traditional infrared reflectography.

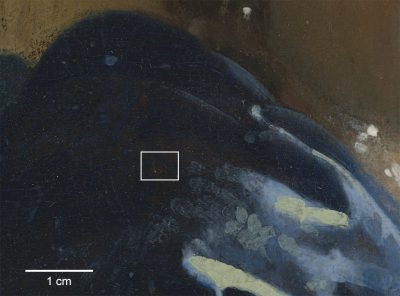

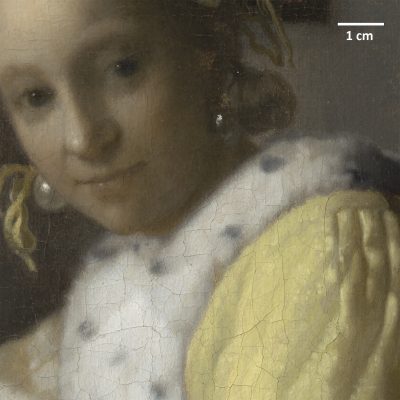

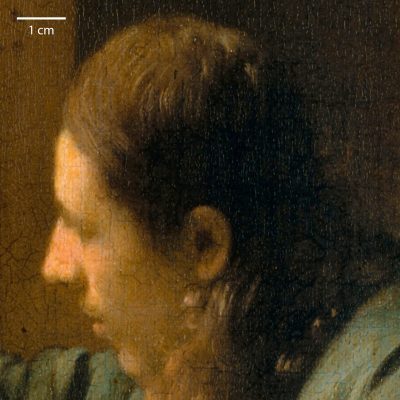

Finally, the information collected through these varied analytical methods was interpreted in the context of the paintings themselves studied at high magnification. Because it is essential to compare paint handling at the same scale, scale bars indicate the magnification when this evidence is presented in close details and photomicrographs (fig. 12).

Vermeer’s Paintings Below the Surface

The materials Vermeer used in his high-life genre paintings, and the stages in which he built up his images, were typical of artists working at the highest level of the Dutch art market in the mid-seventeenth century. He began these paintings with two essential preparatory stages: a brown painted sketch followed by a colored underpaint.18 In his sketch, Vermeer used a linear handling to place both the major compositional elements and smaller details and developed the play of light with broader zones of brown paint to define the shadows. The rare glimpses of the painted sketch that can be seen through the gaps that Vermeer left in the final paint surface show how he defined the contours of forms and areas of shadow.19

He next applied the underpaint over the brown painted sketch, using this preparatory stage to lay out the colors of his composition. By comparison with the calm final surface that we see today, Vermeer’s underpaint was remarkably textured, with more coarsely ground pigments and vigorous, brush-furrowed strokes. In some areas, he used a copper-based drier, presumably the pigment verdigris, to accelerate the curing of slow-drying pigments (notably blacks). The first of our three articles derived from this study, which appears elsewhere in this issue, concludes that in at least two of his genre paintings, Vermeer used this drier more heavily in his underpaint than in the final paint layer—presumably so that he could continue work on the painting’s subsequent stages with minimal delay.20 This material difference from the final paint may have contributed to the pronounced texture of his freely brushed underpaint, which can sometimes be seen in the XRF maps, RIS and IRR images, and occasionally magnified examination21. Elsewhere in this issue, we illustrate the freely brushed character of Vermeer’s underpaint with a detail of the XRF copper map of the tablecloth in Woman Holding a Balance, indicating where a copper-containing material (presumably verdigris) was applied in order to hasten drying.22 To suggest the visual appearance of Vermeer’s underpaint more explicitly, we inverted the map so that the darkest areas correspond to the greatest amount of copper.23 Although he later obscured this rougher brushwork with his fluid final paint, with its finely ground pigments, the robust character of the underpaint filled an essential role, serving as an armature or skeleton that supported and shaped his smooth final paint surface.

With such a small sample set—three surviving tronies, only two of which have been studied technically—we cannot draw firm conclusions. Research to date has suggested that Vermeer did not adopt a different painting practice specifically for his tronies;24 however, notable differences between his handling of paint in the genre works and in the tronies shed light on the role of these intimate paintings within his oeuvre. Finally, the ways in which Girl with the Red Hat specifically diverges from Vermeer’s other works—both his genre paintings and the larger tronies—offer new insights into the development of his late style.

A Reused Painting

Vermeer’s extant oeuvre indicates that he painted almost all his works on finely woven canvases. Canvas weave analysis has established that in one case, at least, he used canvas from the same bolt for both a tronie and a genre painting.25 So ingrained is the idea that Vermeer painted on canvas that the authenticity of both Girl with the Red Hat and Girl with a Flute has been doubted simply because they are the only extant works on panel associated with the artist. However, as we have seen, the 1676 inventory indicates that, at the end of his life at least, Vermeer’s studio supplies included a stock of both panels and canvases on which to paint.26 Dutch artists often chose their painting support based on size; many who almost universally used canvas for medium- and large-format works routinely painted small-scale works on panels. Given this pattern, it would have been natural for Vermeer to paint a small tronie on panel while simultaneously painting larger works on canvas.27 In this context, Girl with the Red Hat’s panel support does not seem out of place.

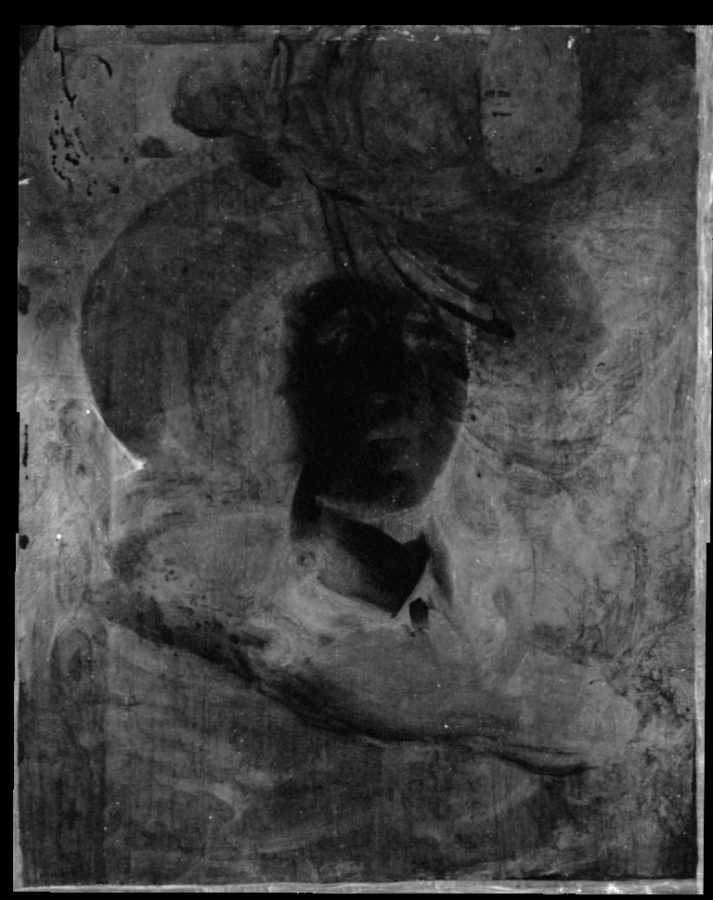

Discussion of this small tronie’s place in Vermeer’s oeuvre is nevertheless complicated by the fact that he painted it not on any wood panel but on one that was previously used. Rather than completely scraping away the unfinished image (a partially completed painting of a man in a large black hat, seen in the false-color IRR, fig. 13), or applying a covering layer over it, he began painting directly on the panel after simply rotating it 180 degrees.28

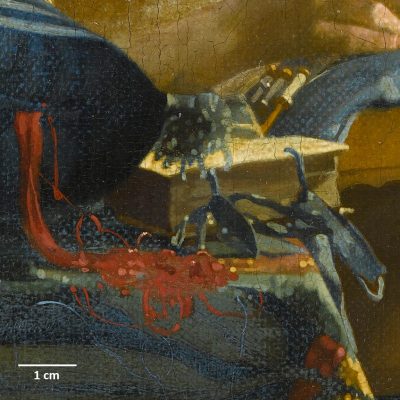

The unfinished painting over which Vermeer worked was prepared according to standard Dutch painting practices. The ground layers are typical of those used on Dutch wood panels: a lower chalk ground followed by a light-tan upper ground, or primuersel.29 Over this, the unknown portrait painter planned out the composition with a monochromatic brown oil sketch, which in this painting seems to have included the pigment umber.30 Although the XRF manganese map (fig. 14) also records this pigment associated with Vermeer’s composition, umber-containing brushwork belonging to the underlying image of the man can be distinguished in distinct places: for example, it describes the darker parts of background wall, particularly on the left where the painter brushed the shadow into the angle where the man’s hat and curling hair overlap. Over this, the painter loosely brushed out an underpaint for a preliminary indication of the composition’s colors. Black pigment used for the hat and mixed into the curling hair is recorded in the false-color IRR. The XRF lead map (fig. 15) clearly shows the face, whitish collar, and collar tie—all painted with substantial amounts of lead white—as well as smaller amounts of lead white mixed into long brushstrokes in the lighted background, where they curve around the brim of the hat, and short, diagonal strokes that describe the man’s garment curving around his shoulder.

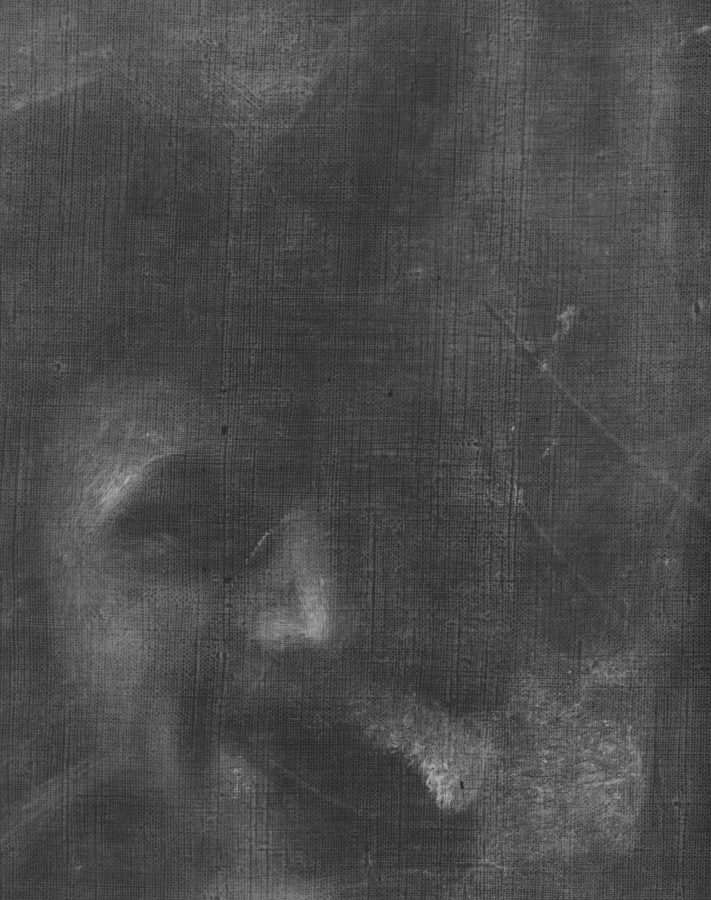

New evidence of the character of Vermeer’s underpaint, its schematic and brushy boldness, prompts a return to the question of who painted the unfinished rendering of the man below, something that has long puzzled scholars. Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., evaluating the portrait without the benefit of new images that reveal the freedom of Vermeer’s underpaint in his genre paintings, considered that the boldly handled, unblended brushwork in the man’s face, and the great flourish of strokes that represent his long, curly hair, were incompatible with the characteristic refinement of technique evident in Vermeer’s finished paintings. This free brushwork, combined with the subject matter of a male bust and the small panel support, led him to suggest instead the possible authorship of Carel Fabritius, at least two of whose paintings, as noted above, evidently hung in Vermeer’s home.31 This idea gained traction with Martin Bailey, who also proposed Fabritius as the possible author, noting vaguely that it was more in that artist’s style.32 However, that notion was roundly dismissed by Walter Liedtke, who instead thought it a “conventional portrait” painted by someone other than Fabritius or Vermeer.33 Benjamin Binstock, meanwhile, believes that the underlying portrait, as well as Girl with the Red Hat, were painted by Vermeer’s daughter Maria.34 In fact, only Jørgen Wadum has proposed that the free handling of the underlying image bears a resemblance to Vermeer’s forceful brushstrokes in his earliest works, such as The Procuress of 1656 (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden), noting the resemblance of the underlying man, with his long curls, to the supposed self-portrait in that work.35 These scholars, however, were comparing the paint handling of the underpaint stage in the unfinished image below the Girl with the Red Hat to the final paint in works by Fabritius and early works by Vermeer. Now that we are better able to see the freedom with which Vermeer generally painted at the underpaint stage, even in his most refined genre paintings from the mid-1660s, the question becomes more complicated.

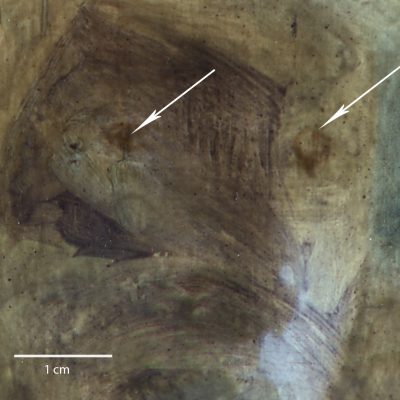

Using the limited technical images currently available, we have begun to reconsider the handling of the man in relation to Vermeer’s underpaint, rather than his finished paint surfaces. When we compare the false-color IRR images of the women in Woman Holding a Balance and Lady Writing to the man in the composition below Girl with the Red Hat (figs. 16, 17, 18), we see two different approaches to underpainting the variations of light falling across a face. In the women’s faces, Vermeer dabbed localized highlights with whitish paint. His brushwork is not visible in the shadows, however, because he painted these areas largely with earth pigments, which are transparent in infrared light.36 By contrast, in the man’s face below Girl with the Red Hat, black pigment was used extensively in the shadows. These different approaches may be evidence of different artists, but they could also simply reflect a conventionalized distinction between techniques used to depict male and female faces.

X-radiographs of The Procuress allow us to make what might be a more plausible comparison—juxtaposing the underpainted man below Girl with the Red Hat with male faces in a genre painting from early in Vermeer’s career (figs. 19, 20)—although the difference in scale must be kept in mind.37 If Vermeer chose to paint over an unfinished work of his own, a likely candidate would be something from much earlier in his career, probably painted in a manner he had long since set aside, perhaps similar to The Procuress.38 In both paintings, white lead was used for male faces in heavily built-up highlights and also (more than in the women’s faces) in thinner shadows. However, there are real differences. The Procuress is a much larger, finished painting (the X-radiograph records the smoothly handled final paint as well as the underpaint), but even allowing for some smoothing by the final paint, the underpaint in the male faces of The Procuress seems much more blended than in Girl with the Red Hat. In the latter, the underpaint’s ragged brushstrokes curve above the eyebrow of the unfinished man, and his cheek is dappled with a pattern of repeated, stabbed strokes.

Finally, we note an additional detail: in the underpainted image of a man in Girl with the Red Hat, the XRF copper map shows that copper is associated with black-containing paints, most likely because a copper drier such as verdigris was added to these slow-drying paints (fig. 21). The copper is most clearly seen in the man’s black hat, where it shows the bold, rhythmic brushwork around the brim that also appears in the false-color IRR. The copper map also shows that Vermeer used such a drier in the final image, particularly in the underpainted shadows of the girl’s red hat. Although we know that Vermeer used a copper drier in the underpaint of his genre paintings (fig. 22), there is currently comparative data from only one other tronie, so it is not yet clear how consistently he followed this practice in all his tronies.39 Vermeer was, of course, not unique in using a copper drier, but because our previous research found him to be the high-life genre painter who did so most consistently,40 it is intriguing to find evidence of this practice in both the unfinished painting Vermeer reused and in Girl with the Red Hat.

While the new evidence we have assembled offers an unprecedented opportunity to consider an enhanced visualization of the unfinished painting in the context of our expanded understanding of Vermeer’s approach to underpainting, current knowledge can neither prove nor disprove Vermeer’s authorship of the underlying image. The possibility cannot be readily dismissed—we have now established that Vermeer painted freely at the underpaint stage41—but free handling does not in itself constitute an attribution. Future research will undoubtedly offer a wider range of comparative material.

Vermeer’s Underlayers for Girl with the Red Hat

The evidence of our technical study suggests that Vermeer worked extemporaneously as he painted Girl with the Red Hat. In some areas he applied only a single layer of paint, repurposing the unfinished painting below to serve as the preparatory layers of his new image; in others, he laid out some of his accustomed preparatory stages as he developed specific details for the final image. Because Vermeer was working directly over an unfinished composition, this small tronie’s earliest layers (the ground application and the painted sketch) cannot be compared directly to his standard painting practices. Nevertheless, the preparatory stages of his own paintings would have offered a similarly textured surface on which he built up his final image, and the broad, open brushwork depicting the man would have allowed the light tan ground to glimmer through a patchwork of brown sketch and underpainted forms in the same way the light-colored grounds on the canvases he used routinely remained partially visible through his own broadly painted preparatory layers.

Preparatory design

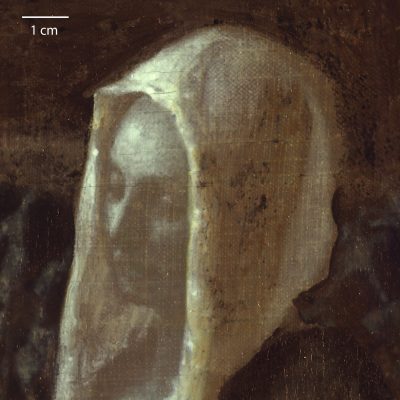

It seems plausible that Vermeer would have begun his tronies (as he did his more formal genre works) with a brown painted sketch; however, this cannot be confirmed in the two tronies that have undergone technical study to date.42 From the evidence available, it seems most likely that in the unusual circumstance of Girl with the Red Hat —painting over an unrelated image—Vermeer did not plan his new composition by superimposing a complete painted sketch over the image of the man. Instead, he probably began at the underpaint stage, varying his practice as needed to plan the new composition with a few quick notations to place essential forms. The woman’s eyes, for example, can be seen as summary swirls of dark paint in the false-color IRR (figs. 23, 24).43 Similarly, Vermeer seems to have positioned the outlines of the robe with dark paint strokes before he worked up the form more fully. Examination with high magnification at the intersection of the neck and robe shows a dark paint stroke that peeks out from under the final paint of the fabric (figs. 25, 26), and microscopic paint analysis confirms that this was not brown, but a colored paint related to the color of the cloak.44 These brief preliminary notations on top of the underlying image may be analogous to a practice Vermeer followed in developing the more complex compositions of his genre paintings, where he occasionally revised details or emphasized forms by “resketching” possible changes onto the underpaint before proceeding.45 In Girl with a Pearl Earring, for instance, there is evidence of an apparently similar practice: fine dark brushstrokes were observed along some contours and a few folds of fabric.46

Underpaint

In his larger tronies, Vermeer handled the underpaint stage with as much bravura as in his genre paintings. Recent research on Girl with a Pearl Earring has revealed a freely handled underpaint stage, so thickly brushed in places that it has a corrugated appearance in the dark background.47 In Study of a Young Woman, magnified images of the surface and an X-radiograph offer glimpses of a brushmarked underpaint below the surface in the face and costume.48

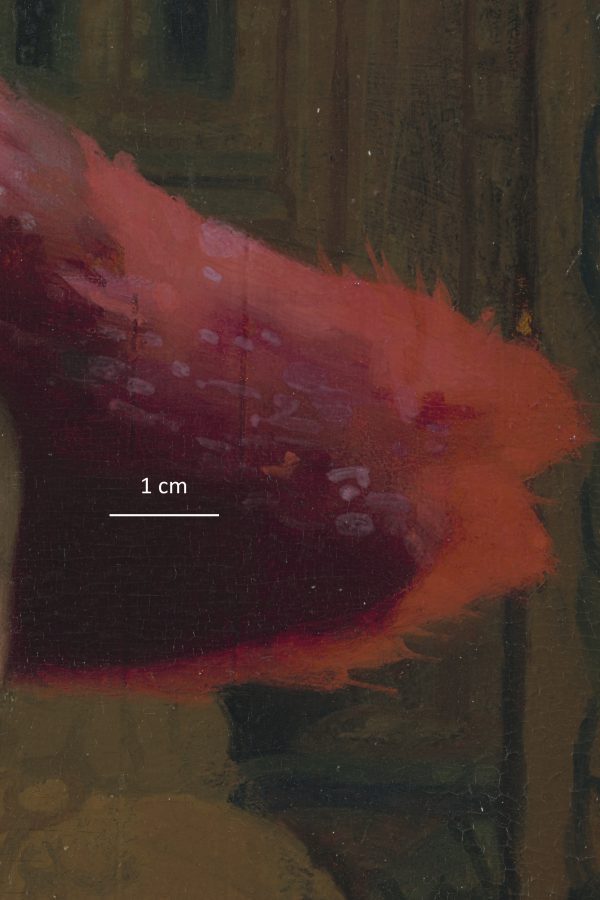

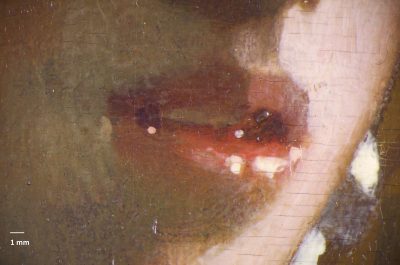

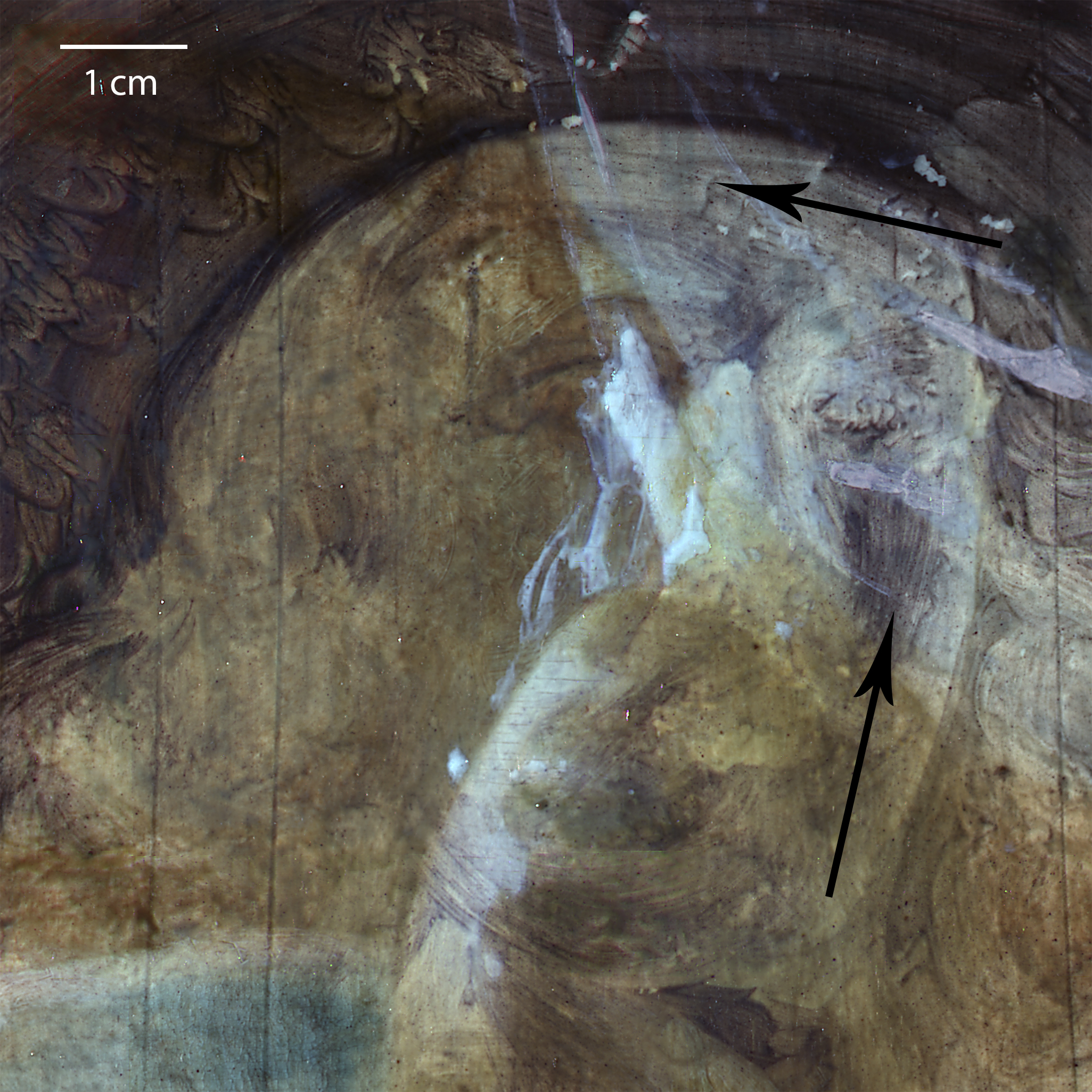

In Girl with the Red Hat, Vermeer’s bold brushwork in the underpaint of the red hat forms a striking contrast to his exquisite control of the final paint. In the underpaint stage, Vermeer seems to have just roughed out the hat, indicating no more than its diagonal orientation with a few wild brushstrokes that extend beyond the hat’s final contours at the upper left. In the XRF mercury map, which plots use of the scarlet pigment vermilion (figs. 27, 28), the brightest pattern coincides with the finished hat, its outer contour varied by tiny feathery strokes of vermilion. Fainter areas of the mercury map, with free brushstrokes that do not appear on the surface, suggest the presence of a vermilion-containing underpaint. In other areas, Vermeer incorporated elements of the image he was painting over as he designed his composition.

An Improvisatory Approach

While painting over an earlier, abandoned composition is not in itself remarkable, the improvisatory ways in which Vermeer incorporated the underlying painting into his final image are more surprising. In the cloak, he allowed the warm brown of the unfinished man’s painted sketch to peek through in the same way that he exploited his own painted preparatory sketch in works such as A Lady Writing (figs. 29, 30, 31, 32). Not only did he adapt the color and texture of the underlying image in some areas, the process of painting over that image may also have contributed—consciously or not—to his inventive approach. For example, we see some of the quickly noted folds of the inverted form of the man’s cloak mirrored in the eccentric diagonal of the woman’s fantastical beret.49 And in the woman’s face, he repurposed the male face below: glimpses of its heavy, pinkish brushstrokes show through his smooth final paint, enlivening the surface as if they were his own underpaint (figs. 33, 34).

Vermeer’s Final Paint for Girl with the Red Hat

Vermeer’s approach in the underpaint stage was not dramatically different in his genre paintings and his tronies. Instead, the distinctive visual character of the tronies was largely achieved in the final painting stage. In Vermeer’s genre works, the tenor of his working practice changed substantially as he painted the final image. After the rapidly handled preliminary stages, he worked more slowly, painting finely ground pigments wet into wet with much smaller brushes, blending or feathering out areas of color to create soft tonal transitions and blurred contours, or applying tiny hovering highlights (fig. 35). Although he sped the drying of his underpaint by adding large amounts of copper drier to slow-drying pigments, he used the drier more sparingly in the final paint, so that his paints leveled to an almost perfectly smooth surface as they slowly dried.50

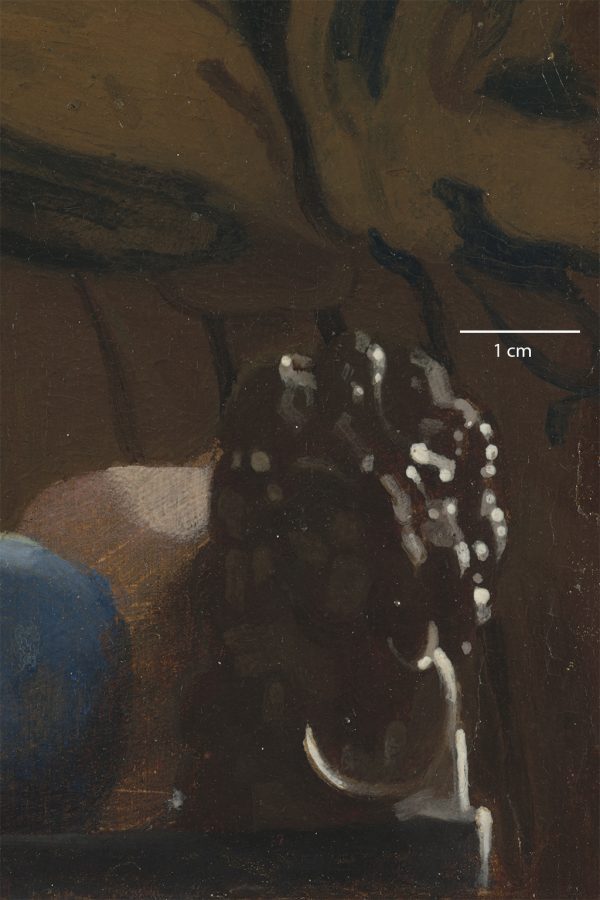

By comparison, in the three tronies—Girl with a Pearl Earring, Study of a Young Woman, and Girl with the Red Hat—Vermeer rendered the costumes using flat planes of color that are only minimally blended, creating broader areas of light and shade than in his formal works. In the two large tronies (Girl with a Pearl Earring and Study of a Young Woman), Vermeer not only worked at a much larger scale than in his genre paintings, but in rendering the folds of fabric he discarded the subtly modulated highlights he had perfected in paintings like A Lady Writing. In these tronies, the fabric’s lighted folds adjoin valleys of deep shadow without mediating mid-tones (figs. 36, 37). Such handling gives the tronies a simplified quality: the figures, and particularly their costumes, are conveyed with the utmost economy.

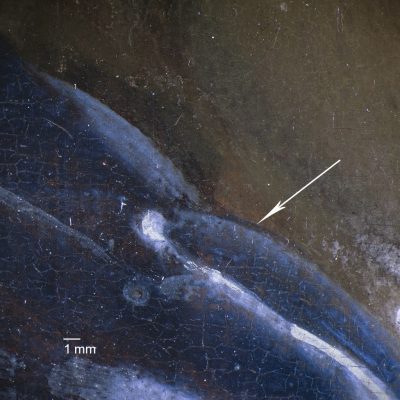

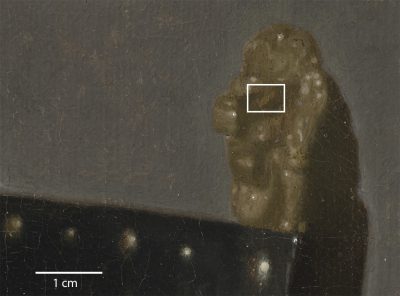

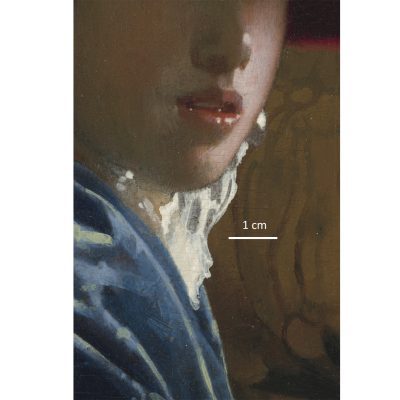

Even in this context, Girl with the Red Hat occupies a special place in Vermeer’s oeuvre. Although he prepared his final paints for Girl with the Red Hat much as he did for his larger, formal genre paintings—grinding the pigments more finely than in his underpaint—his final paint application is remarkably broad and schematic compared to those works. Stark, unblended planes of light and shade give the painting a strikingly abstract quality.51 Vermeer’s abridged approach to the rendering of light effects in Girl with the Red Hat is particularly noticeable in its free handling. Although he worked on a panel roughly half the height of the larger tronies and reduced the actual size of the figure accordingly, he did not use smaller-sized brushes to compensate. In this small tronie, he created a marked contrast between light and shadow in the folds of the cloak, using the same size brush he had used for the larger tronies to quickly apply pale, lead-tin yellow highlights with short strokes that he deliberately did not blend into the deep shadows of the fabric (fig. 38). The figure in Girl with a Red Hat is smaller than those in the large tronies, but it is essentially the same size on the painted surface as the woman in A Lady Writing. This makes possible a point-by-point comparison of paint handling, revealing the degree to which Vermeer’s bold handling in this small tronie diverges from his handling in the formal work (see fig. 35). In the tronie, he made no use of the delicate modulations of tone and tiny circles of highlight that he used in the formal painting to evoke the patterns of light on fabric. The dashes of pink paint he used to suggest feathered highlights on the red hat (fig. 39) are two or three times the scale of the yellow highlights on the sleeve of the woman in A Lady Writing. Even the white reflections on the iconic lion’s-head finial are outsized (figs. 40, 41). The finials in the two paintings are close in size and were painted in the same sequence: Vermeer indicated each first in darker tones, then painted light reflecting off the carved surfaces with strokes and rounded dabs in a mid-tone followed by bright white highlights. In the formal genre painting, the final white touches are limited to a few minute sparks of light; in Girl with the Red Hat, Vermeer created exaggerated white highlights with round drops of wet paint as wide as the mid-tone strokes they accent.52

In fact, Vermeer’s final paint in Girl with the Red Hat has far more in common with the brushmarked texture, broad strokes, and exaggerated contrasts of light and color that we have observed in the underpaint layers of his high-life genre paintings Woman Holding a Balance and A Lady Writing. The strong contrasting colors and dabbed paint strokes in the woman’s cloak are reminiscent of the underpainted tablecloth in A Lady Writing (figs. 42, 43), where Vermeer laid out the pattern of light and shade using thick highlights of boldly applied lead-tin yellow pigment over the dark brown painted sketch, the former visible in the XRF tin map.53 He subsequently softened these stark contrasts in his final paint stage. Similarly, thanks to magnified examination of the surface, we see that the exaggerated contrasts in the final paint of the face in Girl with the Red Hat recalls the high-contrast underpaint in the woman’s face in Woman Holding a Balance. For the latter, Vermeer applied shades of deep brown, light red-brown, and tan paint throughout the underpaint of the neck and face, and soft, paler tones of final paint to mute the stronger colors below.54

In the white kerchief at the neck of the figure in Girl with the Red Hat, we see another feature not found in the final paint of Vermeer’s formal paintings but quite common among tronies by other seventeenth-century Dutch artists—and notably like Vermeer’s handling of underpaint in his more formal works. Here, Vermeer used a tool to remove wet paint, defining folds while simultaneously suggesting the fabric’s translucence (fig. 44); the troughs he created have brush furrows and a rounded shape at the top, suggesting that he may have wiped away the thick white paint with the same wide paintbrush he used to apply highlights on the cloak. In the underpaint stage of A Lady Writing he laid out the yellow jacket by broadly indicating the shadowed back of the sleeve with ochre and quickly dragging a brush through still-wet paint, removing some paint in a shorthand indication of creases. In the jacket, the XRF iron map records these wide furrows (fig. 45).55 The shape and width suggest he used the same type of wide brush there and in the white kerchief in the tronie.56

In comparison with genre paintings such as Woman Holding a Balance and A Lady Writing, Vermeer simplified the illumination in the faces of all his tronies, with broader areas of light and shade. In the two larger tronies, while his handling of the costumes is notably schematic, he nonetheless modeled the faces, the focal points of the compositions, with a more formal, blended technique. Here, as in his genre paintings, he allowed his fluid final paint to flow into the brushstrokes of the underpaint below to create a smooth surface and softened the abrupt transitions from light to dark paint in the face by feathering the edges with a soft, dry brush.57

In Girl with the Red Hat, however, Vermeer seems to have deliberately played up the schematic qualities of his tronies, exaggerating the play of light and exploring the surprising coloristic contrast of a rosy cheek emerging from the greenish shadow cast by the broad hat. He highlighted the cheek with a broad plane of thickly applied paint, using long, vertical strokes; there is little blending into the surrounding paint, and the highlight ends abruptly at the mouth with sharp, hard edges (fig. 46). Again, this schematic paint handling in the final paint of a tronie is reminiscent not of the final paint in his formal works, but the underpaint. In A Lady Writing, for instance, the false-color IRR reveals the sharp tonal transitions in Vermeer’s underpaint, where he depicted highlights on the forehead and cheekbones as patches of white paint. In the final paint he transformed these contrasts into delicately modulated transitions, using minute, interwoven brushstrokes to shape the face and mute the stark contrasts of the underpaint.58

Vermeer’s choice of pigments amplified the unusually abstract quality of this tronie. In the same way that he created a highly contrasted play of light across the face by using abrupt transitions from light to dark, he emphasized the chromatic contrast between the cheek’s bright pink highlight and the unusual green shadow. For the highlight paint, Vermeer used lead white toned with bright red vermilion; he created the darkened side of the face by dragging a thin scumble of greenish paint, composed largely of green earth and other earth pigments, over the dark pinkish underpaint.59 This final application of greenish shadow in the face is an idiosyncratic practice used in some other paintings by Vermeer, one that we have not observed in the work of his contemporaries.60

Like many other tronie painters, Vermeer adopted the deliberately informal practice of leaving some underlayers uncovered. He seems to have followed many of the same painting practices in his tronies that he used in his formal genre paintings. Nevertheless, in comparison to his formal genre paintings, or even his larger tronies, some of Girl with the Red Hat’s most distinctive characteristics point to a radically experimental practice. Not only is Vermeer’s repurposing of a discarded panel unique in his oeuvre, but for much of the final paint in this tronie he used the same comparatively broad brushes that he reserved for the underpaint of his formal works, achieving a bold simplification of forms. We now know that in his genre paintings, Vermeer worked vigorously in the preparatory stage, laying out his composition with confidence. In Girl with the Red Hat, he seems to have explicitly brought the visual qualities of his underpaint stage to the final paint surface. With exaggerated contrasts of light and shade, building his forms with abstract planes rendered in broad, almost unblended brushwork, Vermeer seems to have introduced a new, deliberately informal aesthetic that had implications for his later development.

Part 3: Experimentation and Innovation in Girl with the Red Hat

Even with a sample size of just three tronies, the marked compositional and technical differences between those works and Vermeer’s high-life genre paintings—especially noteworthy in an artist whose working process seems so very purposeful—invite us to consider their significance. What led him to paint tronies in the first place? Was it a desire to explore the creative possibilities of a different genre of painting? Were market factors a consideration? Were the tronies simply an experiment, or can they be linked to a larger evolution in his artistic technique?

Tronies in the Art Market

When Vermeer painted Girl with a Pearl Earring, Study of a Young Woman, and Girl with the Red Hat, it was, somewhat paradoxically, against the backdrop of a general drop-off in tronie production in the Netherlands. The decline has been linked in part to the dwindling number of history painters, who had traditionally been the principal creators of tronies as part of their larger process, and perhaps also to the growing appeal of a more polished, classicizing aesthetic that pervaded Dutch culture after the mid-seventeenth century. It is difficult to understand just why Vermeer might have ventured into this field when he did. Already some twelve years into his career, and with at least twenty-one paintings to his name, Vermeer did not make these tronies as a student exercise (as did so many of Rembrandt’s pupils), nor were they intended as working documents that would help him carry out larger commissions, as was the case for Rubens. The figures’ costumes, while not representative of everyday dress, are hardly the sort of elaborate and overtly dramatic get-ups that tend to characterize such “historicizing” tronies.

In terms of their subjects, Vermeer’s tronies of serene and beguiling young women depart from the traditional sort of highly expressive head studies produced by many northern European artists (see fig. 5), aligning instead with a more classicizing aesthetic that favored smooth, neutral faces expressing a particular ideal of physical beauty and cool perfection, such as those by the enigmatic Brussels artist Michiel Sweerts (1618–1664) (fig. 47).61 Whether of children, young women, or older adults, Sweerts’s tronie heads are characterized by softly defined facial features, liquid eyes, and pensive, almost melancholic, gazes—and in at least one instance, a turbaned headdress not unlike those worn by Vermeer’s models (fig. 48).

The dreamy, elegiac mood of Sweerts’s tronies is uncannily close to that projected by Vermeer’s two larger tronies (as well as many of his genre paintings), and it is entirely possible that he knew Sweerts’s work. Sweerts was in Amsterdam from about 1660 to 1661, prior to his departure on an evangelical mission destined for the Far East; Peter Sutton has suggested that he may have passed through Delft and even met Vermeer on his way north.62 Some of Sweerts’s tronies that bear the closest resemblance to Vermeer’s—for example, his Young Maidservant of around 1660 (see fig. 47)—may well have been painted during his brief stay in the Dutch Republic. A further (albeit indirect) point of contact between the two artists is the painter Louis Cousin (1606–1667). Cousin was Sweerts’s colleague in Rome and (from the late 1650s) in Brussels, and was among the entourage of the French diplomat and connoisseur Balthasar de Monconys on the latter’s visit to Vermeer’s studio in Delft in 1663.63

When Vermeer began painting tronies, just a few years after these speculative encounters, he may have felt an artistic kinship with Sweerts, whose aesthetic was so similarly focused on recording the effects of light and finding equilibrium between naturalism and idealization. The two men handled their works differently—the final paint of Sweerts’s tronies, as in the rest of his works, was applied thinly and with great economy, leaving the colored underpaint visible in many parts of the composition.64 Nonetheless, examples of Sweerts’s later work (i.e., produced after his return north from Italy in about 1654) seems to evidence a distinction between the smoothly brushed final paint and a more brushmarked underpaint, later echoed in Vermeer’s handling of those layers.65 Vermeer’s blended handling in the faces of his larger tronies, consistent with the handling of his genre works, may further suggest that there was an established market for such idealized study heads.

Vermeer’s impetus to make tronies may also have been inspired by close study of similar works in his own collection—particularly those by Carel Fabritius and Samuel van Hoogstraten. The prominent display of these artists’ tronies in the most important rooms of the Vermeer home is an indication of high regard, but beyond that, the relative freedom and informality with which they were painted could have offered Vermeer a tantalizing glimpse of how an artist might deliberately expose the spontaneity and invention of their artistic process. Both Fabritius and Hoogstraten were active in Rembrandt’s studio in Amsterdam in the early to mid-1640s and produced tronies in the shadow of their master, with broadly textured brushwork, strong contrasts of light and shade, and a fascination with fantasy dress.66 Although each had subsequently moved on to other modes of painting by the 1660s, the evident drama of these earlier works could have emboldened Vermeer to adopt similar strategies in his own forays into tronie painting. It is tempting to see such works as offering Vermeer a context for experimenting with a more dramatic play of light on faces than he had previously attempted in either his genre paintings or the larger tronies.

Vermeer’s awareness of the work of his peers and colleagues, plus an effort to distinguish himself within that group for the sake of his artistry and for financial return, may have contributed equally to a decision to paint tronies. While he approached this traditional format with an emphasis on creative experimentation, the deliberate variety (as well as the deviation from his usual production) may also reflect an attempt to reposition himself within the contemporary art market.

Historically, many artists had turned to making tronies not only for the purpose of study and artistic development, but also because they were just the sort of appealing but affordable works that could be readily sold on the open market.67 Modest in scale and ambition, tronies were generally priced accordingly. At Amsterdam auctions held between 1597 and 1638, the vast majority sold for three guilders or less (for reference, it has been estimated that during this period a semi-skilled artisan might earn around one guilder per day).68 Prices assigned to tronies in inventories were generally higher but still quite low: according to one recent survey, the majority of tronies by named artists in seventeenth-century estate inventories were valued at less than six guilders.69 While examples by well-known artists like Rembrandt commanded the highest prices, tronies by (or attributed to) prominent artists could be found at all levels of the market—indicating, perhaps, the popular appeal of a distinctive personal style, as well as an artist’s entrepreneurial savvy in making less costly examples of their work available to collectors of more modest means.70 For the connoisseur, these informal studies, like drawings, offered an intimate glimpse of the artist’s creative process.71 Inventories of even the most prestigious collections show that, despite their inherent informality and affordability, tronies by highly regarded artists were often displayed in the most important public rooms of the home.72

Vermeer may have painted tronies in part to broaden his market appeal with more widely affordable examples of his work. Although documentary evidence is scant, we do have some information as to the relative valuation of his paintings. As we know from the 1696 sale of the Dissius collection with which this article began, Vermeer’s tronies were generally not as expensive as his genre works, which could sell for as much as 175 guilders—or as little as twenty-eight guilders for more modest examples.73 In that same sale, his tronie of a woman in antique dress, “uncommonly artful” (possibly Girl with a Pearl Earring or Study of a Young Woman) was valued at thirty-six guilders, and the “ditto by Vermeer” and “pendant of the same” were valued at seventeen guilders each.74

Whether or not Vermeer’s production of tronies was even partly motivated by economic factors is difficult to reconstruct. He had a certain amount of financial security thanks to an inheritance from his wife’s family; periodic subsidies from his mother-in-law, Maria Thins, in whose house the artist and his family lived; and (from as early as 1657) the financial support of a devoted patron, Pieter van Ruijven, the wealthy collector who owned twenty-one of Vermeer’s thirty-five known paintings, including three tronies.75 Yet even this was probably not entirely sufficient, as Vermeer was also working to support a large family during a period of economic contraction. The United Provinces’ seemingly unassailable financial power had been severely compromised by the Anglo-Dutch wars of the 1650s and 1660s and definitively brought to its knees during the disastrous Rampjaar (Year of Disaster), the French invasion of 1672. A sharp decline in disposable income, as well as an oversupply of paintings, caused the Dutch art market to collapse in the late 1660s and 1670s. Vermeer was not immune to the impact of these events: in April 1676, a few months after his death, his widow testified that “during the recent war with the King of France [Vermeer] had been able to earn very little or hardly anything at all.”76

In producing tronies at this mature stage of his career, Vermeer may have been adopting an approach similar to that of the Amsterdam still life painter Willem van Aelst (1627–1683), who, faced with financial difficulties in the late 1660s, increased and diversified his production, varying the scale and complexity of his works, streamlining their production, and using cheaper materials.77 These strategies paid off for Van Aelst. He continued to produce the luxurious still lifes for which he was renowned, but he now could accommodate more modest buyers as well as the most elite, and within a few years his financial situation had improved dramatically. Although Vermeer appears to have produced at least one tronie before 1664 (the work listed in the inventory of the sculptor Jean Larson), in the latter part of that decade, like Van Aelst, Vermeer may have reconsidered his production in the hope of achieving similar results by appealing to a broader financial segment of the art market. As discussed above, based on the stock of six panels remaining in his studio, which could have been suitable for painting additional tronies, Girl with the Red Hat may not be as much of an anomaly as the surviving works would suggest.

Also like Van Aelst, who produced a series of small, efficiently painted still lifes alongside his larger works in the 1670s, Vermeer produced some simpler, less complex works near the end of his career: small, single-figured genre paintings like The Lacemaker (fig. 49) and Young Woman Seated at a Virginal (fig. 50). As a group, these smaller genre paintings could have been intended to capitalize on his reputation as high-life genre painter while also reaching a more modest level of the art market. These tiny paintings are on the same scale as Girl with the Red Hat, yet they are more allied thematically with his formal genre paintings and, like those larger works, were painted on canvas. It seems likely that Vermeer purchased two commercially prepared canvases at the same time: both canvases are from the same bolt; the grounds are very similar; and the two paintings were originally virtually identical in format.78 The canvas is more coarsely woven than is typical of Vermeer’s larger genre paintings, perhaps a sign of a lower-cost material,79 and the rapid handling suggests that these small works were less time-consuming to make.

Girl with the Red Hat: A Trial Balloon?

Even if the tronies and more simply composed small genre paintings resulted from a pragmatic turn to less labor-intensive productions, Vermeer approached the painting of Girl with the Red Hat with undiminished creativity and, as the technical analysis discussed above has revealed, a willingness to diverge from both his formal genre painting technique and his previous tronie production to explore new creative ground. Although Vermeer’s larger tronies superficially call to mind Sweerts’s softly evocative head studies, his bold and abbreviated handling in Girl with the Red Hat is more reminiscent of tronies produced by Rembrandt and his circle. What we see on the surface of Girl with the Red Hat is, moreover, roughly equivalent to the underpaint stage of Vermeer’s high-life genre scenes: a schematic rendering in broad strokes and exaggerated contrasts of light.

This distinctive approach may indicate that Vermeer was beginning to experiment with a new approach to his artistic practice. A panel with a partially completed portrait, perhaps lying about in the studio, may have made a handy and inexpensive surface on which to test new ideas.80 The practice itself was not uncommon. Examples have been identified in the work of numerous Netherlandish artists, including Jacobus Vrel (active ca. 1654–1662), Jan Steen (1626–1679), and especially Rembrandt.81 Ernst van de Wetering has estimated that roughly a quarter of the self-portraits painted by Rembrandt (or members of his studio) are on previously used supports, along with several tronies and small history or genre scenes mostly produced during that artist’s early career.82 Use of a salvaged support seems to have been more frequent among paintings produced on the artist’s own initiative, whether for him/herself or for the open market, than among commissioned works.

Like countless other artists, Vermeer seems to have considered tronies a forum for experimentation: isolating the young, female models familiar from his genre paintings; varying the scale; using different supports; and in the case of Girl with the Red Hat, employing an unorthodox paint handling reminiscent of his approach to underpaint. This openness to experimentation may also account for his choice of a patterned backdrop in that painting: unusual for tronies and within the context of his oeuvre generally.83 In his genre paintings, Vermeer preferred to set his figures against a plain, light-struck wall, shifting or subtracting elements and adjusting light and shadow to perfect the balance of figure and void. In Girl with the Red Hat, Vermeer instead seems to be experimenting with using intense, saturated colors and brilliant white (the neck scarf), in addition to bold contrasts of light and shadow, to give the figure prominence against a busy background of relatively muted colors.84 Ultimately, he may have decided that this bold introduction of a completely patterned background was best suited to a simple format like a tronie; in the only genre painting in which Vermeer attempted a similar juxtaposition, Mistress and Maid at The Frick Collection, he eliminated the original patterned background, a detailed, multi-figured pictorial element (likely a tapestry or painting), in favor of a plain backdrop that better focuses attention on the central narrative. Although the two figures are now silhouetted against a neutral dark space (fig. 51), the XRF iron map shows a background with a building, trees, and a group of figures (fig. 52).85

By incorporating “genre-like” elements of a tapestry-hung wall and a familiar chair in Girl with the Red Hat, Vermeer also seems to be edging toward a conceptual merger of tronie and narrative genre. Many of his genre paintings explore the expressive potential of a figure absorbed in private, contemplative activities—reading, making lace, the simple act of pouring milk—while others invite our participation or complicity with an outward glance. In both instances, the viewer, whether voyeur or accomplice, becomes part of the artist’s narrative. Vermeer’s tronies, on the other hand, present captivating figures removed from temporal or spatial specificity and invite viewers to weave their own narratives. With its moderately articulated setting, Girl with the Red Hat offers just enough familiar material to initiate this imaginary dialogue.

As further evidence of its uniquely experimental character, Girl with the Red Hat may also be linked to the change in Vermeer’s handling of paint that that we see in his later work. Although it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions based on an extant corpus as small as Vermeer’s, his approach in Girl with the Red Hat —and perhaps in other small tronies, now lost—appears to announce that shift. Adopting the visual qualities of his underpaint for this work’s final image opened the way for later works characterized by highly schematized forms depicted with strong contrasts of light and shadow as well as distinctive chromatic contrasts, including the introduction of greenish skin tone shadows based on green earth.86 This increased abstraction appears not only in small works on the scale of the tronies, like The Lacemaker (ca. 1669–70) (see fig. 49), but also in genre paintings as large as Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid (ca. 1670) (fig. 53), both produced at the very end of the decade.

The Lacemaker offers one of the most compelling examples of Vermeer’s increasing turn to abstraction. A bright wash of light centers the composition, gathering the woman’s absorbed face, her nimble hands, and her lacemaking tools in a pool of illumination. Vermeer eliminated nearly all detail, translating the essentials of figure and action into a deceptively simple painted network of highlights and shadows. Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid, one of the most audacious works of Vermeer’s late career, uses light streaming in through the window to create sharp juxtapositions of light and shade. The writer’s proper right shoulder, cap, and cheek are illuminated and set against a deeply shadowed wall, while her proper left shoulder, cap, and cheek are plunged into darkness, contrasting with the wall’s bright white plaster.87 The difference between the emphatic light in these compositions and the gentle daylight that flows over the smooth features of the woman in A Lady Writing, painted just five or six years earlier, is deliberate and pronounced. To transform his light, Vermeer transformed his handling of paint.

In these works from the late 1660s and early 1670s, he defined faces with sharp-edged patches of highlight that trace the bridge of the nose and curve around the inner corner of the eye (figs. 54, 55). The highlights on the faces in these late works have an antecedent in the sharply defined patch of light that curves around the mouth of the sitter in Girl with the Red Hat (fig. 56), handling that is far distant from the delicately modulated final paint in A Lady Writing, where Vermeer muted the strong contrasts of his underpaint (fig. 57).

In painting the costumes and fabrics in the later works, he placed bright, angular highlights against deep shadows. In the sleeves of the figures in both The Lacemaker and Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid, the harsh contrast between highlight and shadow is not eased by any intermediate halftones. This is a striking difference from his earlier works like A Lady Writing, where softly curving folds in the sleeve are described with rounded touches of paint in incremental differences of light and dark. Again, Girl with the Red Hat seems to be a point of transition: Vermeer’s quick dabs of light paint on the cloak are outsized echoes of the rounded touches in A Lady Writing, while his bright strokes of highlight set against dark troughs of shadow anticipate the geometric and suggestive handling of later works. In these late works, Vermeer’s free handling allows the material qualities of his paint to play an expressive role. He conjured the white lacework of the cap in Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid (see fig. 53) and the colored threads cascading from the sewing cushion in The Lacemaker (fig. 58) with remarkably fluid dribbles of paint, each accented with round dotted highlights of the same color. This free handling recalls the untamed wisps of vermilion paint that flicker along the edge of the beret in Girl with the Red Hat. The round highlights that harmonize with the surrounding colors—white dots on the white lacework, pinkish dots on the red threads—recall the dabs of pink in the sitter’s red hat and glistening spots of colored light on her lip and her eye: pale green for the greenish shadow of the eye, pale pink at the darkened corner of the mouth (fig. 59).

(Re)Dating Girl with the Red Hat

With Girl with the Red Hat’s anticipation of so many stylistic and technical features that became key in Vermeer’s later work, it can be argued that the painting should not be grouped with the two larger tronies and dated in the mid-1660s but ought to be dated to around 1669—a year in which we witness a profound shift in Vermeer’s technical evolution. The painting’s experimental character has historically stymied scholars seeking to fit it within a linear stylistic development. Shortly after its discovery, Tancred Borenius (1925) and Wilhelm Valentiner (1932) dated it to about 1660 and 1658 respectively, seeing a likeness with the textured pointillism of Vermeer’s early genre paintings such as The Milkmaid. Others, including André Malraux (1952), Lawrence Gowing (1952), and Leonard Slatkes (1981), preferred to place it later in the artist’s career, to the end of the 1660s and beginning of the 1670s.88

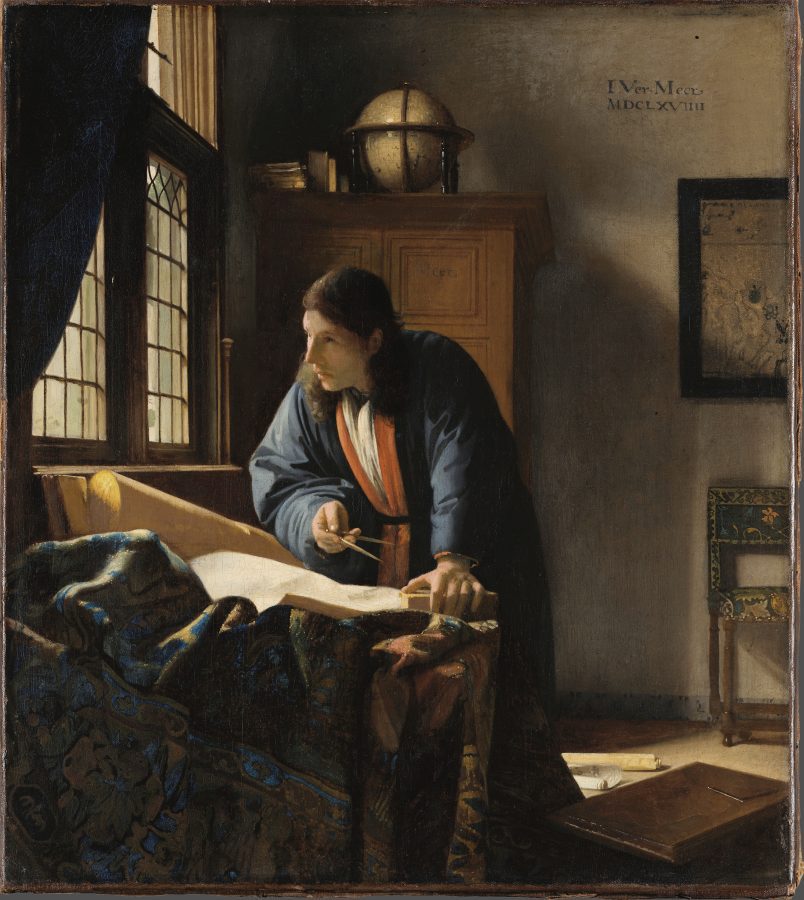

Since Girl with the Red Hat entered the collection in 1937, the National Gallery’s own dating of the painting routinely shifted until Wheelock, in 1981, proposed a range of about 1666/1667.89 In 1995, noting the likeness between the way Vermeer applied highlights in the tronie and those in the chandelier and tablecloth in The Art of Painting from around 1667 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), he observed: “These similarities, as well as the comparably generalized forms of the girls’ heads in the two paintings, argue for a close chronological relationship. It seems probable that both works were executed around 1666 to 1667, slightly before The Astronomer (Louvre, Paris), which is dated 1668.”90 This dating would potentially place Girl with the Red Hat between Girl with a Pearl Earring, of about 1665, and Study of a Young Woman, of about 1665–1667. Yet, considering our research, a date of around 1666/1667 for the small panel now appears too early. Its clear affinities with the later genre paintings suggest instead that it was part of a technical and stylistic experiment that opened the way to a new era in Vermeer’s work.

Vermeer rarely dated his paintings, but The Astronomer and The Geographer, dated in two successive years (1668 and 1669, respectively; figs. 60, 61), offer intriguing material evidence of just when this new abstraction entered Vermeer’s practice.91 Because of their compositional affinities and similar subjects, it has often been suggested that these works were pendants; recent canvas weave analysis strengthens this proposal, confirming that the two supports came from the same bolt of canvas.92 The two compositions are, indeed, closely related, with the same model depicted in almost identically furnished rooms. In most areas, Vermeer used the same visual vocabulary: for example, depicting in each painting a crumpled carpet with dotted highlights that simultaneously depict the play of light and suggest the tufted texture of the textile. In both paintings he inscribed the same signature onto the cabinet behind the figure: “IVMeer,” with “IVM” in monogram.

However, Vermeer also signed The Geographer a second time, adding a variant signature (“I.Ver Meer”) and the date in Roman numerals on the rear wall. In The Astronomer he simply inscribed the date (also in Roman numerals) below the signature on the cabinet. Because Vermeer almost never dated his paintings, it is worth noting that he made a point of recording different dates on this pair—possibly adding this information to both paintings after he completed The Geographer. The two paintings’ differing dates align with small but significant differences in painting technique. In The Geographer, Vermeer’s composition encompasses more of the window and places the figure closer to this light source. In this painting (but not in The Astronomer) he also seems to have returned to further develop the fall of light by adding or reemphasizing certain highlights. Where he had first used a dark yellow highlight in the opening of the rolled map below the window to suggest light transmitted through paper, he later amplified this optical effect, building up a schematic patch of thicker and brighter yellow paint.

He also first painted both faces with similarly blended brushwork ranging from warm highlights to cool, gray-green shadows, but in The Geographer he reemphasized the light from the nearby window by adding thickly brushed, bright pink paint on the illuminated side of the face, creating a hard-edged, planar highlight curving around the high forehead and tracing the bridge of the nose (figs. 62, 63). This revised patch of light is reminiscent of the final, bright pink highlight on the cheek of Girl with the Red Hat; as in the tronie, the highlight amplifies not only the contrast of light and dark but also the chromatic contrast between green and pink tones in the face (figs. 64, 65). It also seems to look forward to the schematic planes of highlight that were integral to Vermeer’s wet-into-wet handling soon after, in the faces of The Lacemaker and Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid.

We suggest that after he completed The Astronomer, Vermeer drew on the success of his experimentation in Girl with the Red Hat to add newly abstract highlights to the former’s pendant, The Geographer, recording the date 1669. Using painting techniques that are analogous to the underpaint stages in his genre paintings from the mid-1660s, the deceptively modest Girl with the Red Hat inaugurated the heightened abstraction and greater contrasts of both light and color that became hallmarks of Vermeer’s later works. Thus, we date Girl with the Red Hat to around 1669.

Conclusion

Our conclusion that Vermeer’s approach to painting tronies was deeply thoughtful and creative may not be unexpected for an artist as deliberate and exacting as he was. However, when considered within the broader context of his oeuvre, our findings regarding the careful choices of materials and paint handling evident in the tronies have shifted our understanding of Vermeer’s conceptual and technical working methods. As the only surviving painting of its kind, Girl with the Red Hat is especially consequential to understanding Vermeer’s evolution as an artist. Instead of a somewhat idiosyncratic digression from the high-life genre paintings for which he was better known, it seems instead to represent a conscious experiment with bolder, more abstract brushwork and more highly contrasting pigments. In the years to come, he would ultimately adopt this approach to painting even in his high-life genre work. Our assessment of Vermeer’s tronies, and especially Girl with the Red Hat (fig. 66), has thus provided us with a new framework through which to consider Vermeer’s approach to his craft and, as our paper elsewhere in this issue addresses, a new set of questions to pose of the puzzling Girl with the Flute (fig. 67).93