The inventories of three seventeenth-century art dealers in Amsterdam containing hundreds of paintings with an average value of less than 4 guilders show a high concentration of history painting. This essay explores the mass market for history painting in Amsterdam in the Golden Age by analyzing the stocks-in-trade of three art dealers: what did the art dealers sell, and how did they manage to sell history painting at such low prices? As an example, works by Barend Jansz. Slordt, who produced history painting in large numbers for one of the art dealers, will be studied closely to acquire insight into production costs: what materials did Slordt use and what methods did he apply to paint as economically as possible?

According to seventeenth-century art theory, history painting was the highest possible aim for an artist. Such textually based figure paintings derived their subjects from the Bible, classical mythology, classical history, and postclassical literature. By demonstrating his supreme skill in a historia, the artist could obtain eternal fame.

A number of factors have contributed to the general notion among art historians that the purchase of history paintings was limited to the intellectual and financial elite. These include the complexity of the content of these paintings, together with the fact that the most renowned artists of that time, such as Rubens and Rembrandt, were primarily history painters as well as the high value estimates—over 1,000 guilders—for these paintings in seventeenth-century inventories. But an observation by Samuel van Hoogstraten (1678) suggests that such a conclusion may be unwarranted: “For we reject everything that is without artistry and disapprove of what cannot hold its place among good things. Otherwise the third and highest degree [of painting = history painting] would be the most contemptible, for we see everywhere illustrious histories that are a dime a dozen.”1

This article will present historical documents that support Van Hoogstraten’s statement that a large market for relatively cheap history paintings existed in the Golden Age. From these documents it appears that these “dime a dozen” paintings were not merely anonymous workshop copies or imitations but also inexpensive “original” paintings produced in multiples by minor artists. By analyzing the inventories of three Amsterdam art dealers who owned enormous stocks-in-trade of paintings of religious subjects with an average value of less than 4 guilders, this essay will explore the mass market for history painting, the painters involved, the subjects represented, and the cost-saving production methods that they used.

Three Art Dealers

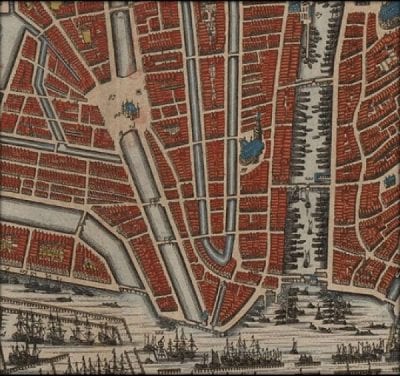

The three art dealers whose inventories will be studied all had shops located close to the Amsterdam Nieuwmarkt, on a small stretch of Kloveniersburgwal, between Koestraat and Bethanienstraat (fig. 1). The Nieuwmarkt square, which featured the headquarters of Saint Luke’s Guild in the Waag, an annual market for luxury goods, and many surrounding streets with artisanal workshops, was a lively center for art production and trade in the seventeenth century and therefore an excellent location for a painting shop. In fact, in the second half of the seventeenth century, several other art dealers with cheap stocks-in-trade were located around the corner in Koestraat. This is further indication that this was the preeminent place in Amsterdam to obtain affordable paintings. The three shops used as case studies for this article provide exceptional opportunities for research because of the survival of detailed inventories with information about subject matter and value of their entire stocks.

The first shop to consider is that of Jan Fransz. Dammeroen (1605–1658). When Dammeroen was in Rotterdam selling paintings at the annual fair in September 1646, two men visited his wife in Amsterdam to demand the reimbursement of 837 guilders. She was unable to pay them at the time, but as collateral she promised them the paintings that would remain unsold after the fair. These remaining works were inventoried when Dammeroen returned to Amsterdam a day later and consisted of 127 paintings.2 One-and-a-half weeks later the landlord of his house and shop made a claim for more than 630 guilders for two years of overdue rent, which Dammeroen could not pay.3 As a result, the art dealer had to move out of the property and was declared insolvent by the Desolate Boedelkamer of the local court. An inventory of Dammeroen’s shop—the contents of which had to be auctioned to pay back his creditors—was drawn up on September 21, 1646.4 His belongings, consisting of 213 paintings (none of them with the name of the artist), painting utensils, furniture, and other possessions, were auctioned by Thomas Jacobsz. Haringh.5 Haringh was the concierge of the Desolate Boedelkamer and the same auctioneer who presumably handled Rembrandt’s bankruptcy ten years later.6 The Dammeroen sale yielded 557 guilders;7 when this figure is divided by the number of paintings, the average value per painting was 2.6 guilders. The actual average was lower because in addition to the paintings other items such as furniture were auctioned.

Shortly after Dammeroen’s bankruptcy the art dealer Cornelis Doeck (ca. 1613–1664) took over the shop space. After the payment issues the owner of the building had had with Dammeroen, he preferred not to rent it out again and sold the property to Doeck.8 Doeck and his wife both died in May 1664 at the beginning of an outbreak of the plague.9 The next of kin had an inventory of the inheritance drawn up only in December 1666; the contents of the shop followed half a year later.10 The stock-in-trade consisted of 576 paintings (284 included the name of the artist, 1 appeared to be a copy), a number of gedoodverfde (dead-colored) panels, frames, and an unspecified number of books.11 The public auction of the shop’s contents lasted five days in February 1668 and was performed by Pieter Haringh, a cousin of the before mentioned Thomas Jacobsz. Haringh.12 The contents of the shop yielded 2,562 guilders; suggesting an average value of 4.5 guilders per painting.13 However, the real average must have been considerably lower, probably less than 4 guilders, since the other contents, particularly the collection of books, most certainly constituted a significant portion of the total proceeds.14

Our third art dealer, Hendrick Meijeringh (1639–1687), lived only two doors down the canal from Doeck. Along with fellow art dealers Jan de Kaersgieter and Elisabeth Hoomis (who operated her shop two blocks away on Kloveniersburgwal and also sold cheap paintings),15 he was registered to attend the auction of his neighbor Doeck. Meijeringh bid on paintings for the shop of his father Frederick Meijeringh.16 When his father died in 1669, Hendrick, as eldest son, inherited the shop and all its contents. In his own testament Hendrick declared his brother, Albert Meijeringh, as universal heir.17 Albert became quite a successful painter in his own right and left Amsterdam shortly after his father’s death in the company of Johannes Glauber to travel in France and Italy.18 Hendrick added a sewing workshop to the Meijeringh business, which was managed by his sister and her husband, who was a tailor.19 The art dealer was buried on June 12, 1687, and eight days later the inventory of his estate was drawn up.20 The stock of the painting shop included 488 paintings, for 252 of these the name of the artist was given; it also contained unpainted panels and canvases, frames, and painter’s equipment.21 Meijeringh was, although to lesser extent, also active in the market for copies. This is demonstrated by the fact that 39 of his paintings were described as “copies after prints or paintings.” Although information about the total value of Meijeringh’s stock is lacking, his buying activity at the auction of Doeck’s estate, as well as the frequent similarities in artist names and subject matter between the two shops, indicates that Meijeringh was active in the same segment of the art market as Doeck.22 He probably took over a substantial part of Doeck’s stock and must have sold paintings of the same type and value. At the outset, the two neighboring art dealers probably were vigorous competitors.23

The three art dealers had more in common than the location of their shops. All three of them had very large stocks-in-trade of paintings. Although Dammeroen had only 213 paintings when his shop was inventoried, one must consider that he was selling paintings in Rotterdam just one-and-a-half weeks earlier and that the 127 paintings given to creditors as payment were those left in his possession after the fair. It can thus be assumed that he started with a much larger stock. Doeck had 576 paintings in store when he died, and Meijeringh had 488 paintings. The relatively low value of the paintings is another striking resemblance. With their stock having an average value of less than 4 guilders, the art dealers appear to have served a much more modest clientele than, for example, “gentleman-dealer” Gerrit Uylenburgh, who in 1675 had 176 paintings in stock with an average value of 136 guilders.24 Uylenburgh had a high-end stock of sixteenth-century paintings that included works by famous Flemish, French, and Italian artists, as well as the most celebrated Dutch artists of his (and our) time, such as Rembrandt, Caspar Netscher, and Jacob Backer. The three art dealers studied in this article obviously sold much less prestigious works than their high-end colleague Uylenburgh. With the exception of the winter landscape by “Brueghel the Elder” listed in Meijeringh’s stock (most probably a copy), no foreign artists or Old Masters were recorded in their stocks-in-trade. The painters listed were contemporary, mostly active in Amsterdam, and many of them are unknown to us today.

Analysis of Stock-in-Trade: Painters’ Reputation

In order to offer insight into the artistic status of the painters whose works were handled in these three shops, it is necessary to assess their reputations. The main purpose is to find out whether the artists were well known in their own time. The total sample consists of eighty-three painters. Dammeroen’s inventory does not contain painters’ names, but the Doeck and Meijeringh inventories list forty-nine and forty-five painters respectively, of whom eleven appear in both inventories.25 I have divided these eighty-three painters into four groups; based on their occurrence in different sources (see Table 1 and Appendix 1). The chosen method for indicating reputation follows the model of Clara Rasterhoff in her recent dissertation on the painting and publishing industries; I have simplified the model and I have added two groups to match our specific sample.26 Group A reflects the appreciation of art historians today and includes all painters mentioned in The Grove Dictionary of Art or/and Bob Haak’s standard work The Golden Age: Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century. Groups B and C reflect the appreciation of contemporaries, such as painters, connoisseurs (liefhebbers), and collectors. Where Group B displays the painters mentioned in the painter biographies by Arnold Houbraken and Johan van Gool; group C includes all painters that are listed in household inventories collected in the Montias Database at the Frick Collection (1,280 Amsterdam inventories, 1597–1681) and the Getty Provenance Index Databases (8,192 Dutch inventories, 1620–1750). Please note that groups A to C overlap. Group D (the “remainder group”) includes painters that are not named in the before-mentioned sources.

| Table 1a: Painters included in the combined inventories of Doeck (1667) and Meijeringh (1687) divided into gradually expanding (and overlapping) reputation categories on the basis of their appearance in different sources | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reputation categories determined by appearance in different sources | Sample of 83 painters* | ||||

| Ranking | Total of early modern Dutch painters | Number of painters | Percentage of painters of total sample (not cumulative)** | ||

| A Prominence today Source: Haak, The Golden Age: Dutch Painters of the Seventeenth Century; The Grove Dictionary of Art | 266 | 29 | 34% | ||

| B Contemporary Prominence Source: Houbraken, De groote schouburg; Van Gool, De nieuwe schouburg. | ±500 | 21 | 25% | ||

| C Contemporary Ownership Source: Montias-Frick Database; Getty Provenance Index | ±1500 | 48 | 58% | ||

| D No Appreciation or Ownership*** | - | 29 | 35% | ||

| Source: SAA 5075, inv. no. 2733, fol. 473–79, 13-07-1667; SAA 5075, inv. no. 2414, 20/25-06-1687; Clara Rasterhoff, “The Fabric of Creativity in the Dutch Republic: Painting and Publishing as Cultural Industries, 1580–1800” (PhD diss., University of Utrecht, 2012), 206–10. * The sample is composed of the painters mentioned in the combined inventories of Doeck (1667), in which 49 painters are listed, and Meijeringh (1687), in which 45 painters are listed; 11 painters appear in both inventories. ** The number of painters in the sample in the different categories is here expressed as a percentage of the total sample of 83 painters. The categories are expanding and overlapping, for instance, a painter in ranking A is present in all categories except D. Therefore, the sum of this column exceeds 100%. *** Group E is a remainder group and consists of the painters in the sample that are mentioned in the inventories of Doeck and Meijeringh but not in any of the above-mentioned sources. |

|||||

As can be seen from Table 1, Group A consists of twenty-nine painters in our combined Doeck/Meijeringh sample that are appreciated by art historians today.27 Of these painters, eleven, such as Nicolaes Berchem and Pieter Claesz, are also part of Group B, demonstrating that their reputations withstood the test of time. There are eighteen painters included in Group A that are not mentioned in contemporaneous art literature and therefore presumably did not belong to the most prominent artists of their time. Among them, we find Jan Beerstraten and his son Abraham Beerstraten. The Grove Dictionary of Art aims to register painter families and as a result, some less prolific painter families such as the Beerstratens or less successful family members of prominent artists, such as Jacobus Storck (brother of the more prominent artist Abraham Storck), are included. Jacobus Storck is in fact mentioned in passing by Houbraken in the biography of Abraham, yet without his name. He is identified as “a brother who painted Rhine-views and inland vessels, although not so artful.”28 Now-celebrated artists such as Meindert Hobbema and Wouter Knijff were also not part of the eighteenth-century canon.

| Table 1b: The number of works of art attributed to the painters in the four different reputation categories; and the share of the categories in the total number of attributed paintings | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | ||||||||||

| number | % | number | % | number | % | number | % | ||||||

| Cornelis Doeck | 84 | 30 | 50 | 17 | 111 | 39 | 136 | 48 | |||||

| Hendrick Meijeringh | 28 | 11 | 44 | 17 | 88 | 35 | 132 | 52 | |||||

Group B consists of the painters mentioned in the painter biographies by Arnold Houbraken and Johan van Gool.29 These twenty-one painters constitute 25 percent of our sample, which means that 75 percent of the painters were not part of the eighteenth-century canon of artists. The lack of seventeenth-century literary sources that reflect the contemporaneous canon made it necessary to rely on the eighteenth-century painter biographies of Houbraken and Van Gool.30 Note that only nine of the total group of twenty-one painters (Nicolaes Berchem, Job Adriaensz. Berckheyde, David Colijns, Barend Gael, Dirk Maas, Paulus Potter, Abraham Storck, Jacob Toorenvliet, and Adriaen Verdoel) were thought to deserve their own biography by Houbraken or Van Gool. The others were only mentioned in passing in other biographies, and more often with a negative judgment than a positive one. For example, Willem Dalens is mentioned in the biography of his son Dirck Dalens as “a painter, not of the best kind.”31 The nine painters who did receive an entry in eighteenth-century art literature should therefore be considered the only prominent figures in our sample. Their paintings, which constitute only a small percentage of the total stock of the shops (1 percent of the total stock of Doeck and 3 percent of the total stock of Meijeringh), must have been the most expensive in the shops of Doeck and Meijeringh.

Group C consists of forty-eight painters listed in household inventories up to 1750, which are collected in the Montias-Frick Database and the Getty Provenance Index Databases.32 The Montias-Frick Database only includes Amsterdam inventories, but the Getty database also contains inventories from other Dutch cities, such as Haarlem, Utrecht, and Dordrecht.33 The painters represented by at least one painting in one or more households in these inventories make up over half of our sample of painters. In this group we find minor masters that are not included in the former groups, such as Arnoldus Anthonissen, Adriaen and Cornelis Gael (uncle and father of Barend Gael) and Albert Klomp. The representation of painter names in inventories reflects the extent to which the painters’ style and signature are recognizable among those of their contemporaries, and, moreover, the importance of “the name” or the attribution in determining the value of the painting. It is telling that Adriaen Verdoel, who received an entry in Houbraken’s book, is not mentioned in any inventory. He was probably only discussed because Houbraken mistakenly believed he received his painter’s training from Rembrandt.

Group D is the “remainder” group. It consists of 29 painters who are mentioned exclusively in the inventories of Doeck and Meijeringh and therefore had no discernible contemporary reputation. This group of painters accounted for most of the works in the art dealers’ stock: of all attributed works, half of them were painted by a painter from Group D (see Table 1b). Both inventories suggest that at least one painter produced exclusively for the shop: Doeck had 64 painting by the painter Leendert de Laeff, and Meijeringh had 69 paintings by Barend Jansz. Slordt. These painters worked in the attics of the shops and mass-produced paintings for the art dealers; a practice that in contemporary art theory was compared with slavery and considered shameful.34 In addition to their absence in art literature and inventories, information available in the form of archival sources or signed paintings is extremely limited for these painters. The painters “Juffrouw Bega” [Miss Bega], “Van der Bent,”35 Pieter Blockman, “Van Dor,” “De Fuyter,” “Gercken,” J. Holsloot ,and “Schutt” could not be identified at all. Basic biographical information such as place and year of birth is often lacking, as in the cases of Leendert de Laeff and Willem Gras. No signed paintings are known by the painters Jan van den Broeck, Gijsbert Cruijsbergh, Barend Faber,36 Mathijs Vervoort, Arnoldus Schaep, Gerrit Schimmel, and Pieter Wiggersz.

This analysis shows that most of the painters represented in the Doeck and Meijeringh inventories were minor figures and many of their names were only recorded in these documents. A large number of the painters who worked for Doeck and Meijeringh were unknown in their own time as well as in ours. It is significant that more than one-third of the painters in our sample are not recorded anywhere else. This means their works were relatively cheap, since identified paintings in inventories reflect the importance of the painter’s name for establishing the value.37 The presence of their names in these two dealer inventories, as opposed to private inventories, can be explained by the expertise present. The dealer inventories were drawn up with assistance from family members active in the business, who were, therefore, well acquainted with the shop’s administration and may have known personally the artists the shop employed. There were likely account books that recorded the names of painters available in the art shops. This may explain why the Dammeroen inventory does not contain any artists’ names. This inventory was drawn up by a clerk of the Desolate Boedelkamer, who most likely lacked the expertise to identify minor masters and moreover did not care to list them, because they were of no importance for the paintings’ value. It is, however, highly likely that Dammeroen worked with painters of similar reputation as the ones listed in the inventories of Doeck and Meijeringh. The lack of painters’ names in the inventory of Dammeroen’s shop, together with the low average value of the paintings, suggests that there were no works present of masters worth mentioning by name.

Analysis of Stock-in-Trade: Subject Categories

For the analysis of the stocks-in-trade of art dealers Dammeroen, Doeck, and Meijeringh, the descriptions of the paintings in their inventories were put into eight categories as listed in Table 2: history, landscape, marine, still life, pastoral (scenes without reference to mythology or literary sources), genre, portrait, and “other.” This study considers all textually based figure paintings with subjects from the Bible, classical mythology, classical history, or postclassical literature in the category of history painting. The category “other” consists of minor categories lacking a significant number of paintings. Paintings without reference to a subject (een schilderij, een stuckie) are grouped into the category unknown/unspecified.

| Table 2: Paintings included in the inventories of Dammeroen, Doeck and Meijeringh divided by Genre Categories | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dammeroen (1646) | Doeck (1667) | Meijeringh (1687) | ||||

| number | % | number | % | number | % | |

| History* | 88 | 41% | 246 | 43% | 200 | 41% |

| Landscape | 30 | 14% | 166 | 29% | 156 | 32% |

| Marine | 7 | 3% | 47 | 8% | 37 | 8% |

| Still life | 17 | 8% | 33 | 6% | 10 | 2% |

| Pastoral | 15 | 7% | 35 | 6% | 1 | 0% |

| Genre | 7 | 3% | 19 | 3% | 22 | 5% |

| Portrait | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 1% |

| Other | 11 | 5% | 16 | 3% | 18 | 4% |

| Unknown/unspecified | 37 | 17% | 14 | 2% | 41 | 8% |

| Total | 213 | 100% | 576 | 100% | 488 | 100% |

| Identified subjects | 83% | 98% | 92% | |||

| Identified artists | 0% | 49% | 52% | |||

| Source: SAA 5072, inv. no. 572, fol. 163–69, 21-09-1646; SAA 5075, inv. no. 2733, fol. 473–79, 13-07-1667; SAA 5075, inv. no. 2414, 20/25-06-1687. * The category “history” includes all textually based figure painting: paintings with subjects from the Bible, classical mythology, classical history, postclassical literature, and allegorical subjects. |

||||||

Table 2 reveals three interesting results. Firstly, it is significant that 83 percent, 98 percent, and 92 percent, respectively, of the paintings in the stocks of Dammeroen, Doeck, and Meijeringh are described in enough detail to be categorized according to subject matter. The number of paintings with subject description is thus considerably higher than the number of works for which the name of the artist is given (none in Dammeroen’s stock, 49 percent in Doeck’s stock and 52 percent in Meijeringh’s stock). This suggests that the depicted subject was the most distinguishable identifying characteristic of these paintings, and therefore, that the stock of these art dealers mainly focused on subject matter, rather than the reputation of the artists involved in the execution.

Secondly, some of the “modern” genres of painting that at the time were produced in large numbers for the open market, such as still life and marines, remain minor categories in the shops of these art dealers. Note also the almost entire absence of portraits. Only a single painting portraying “several princes” was listed in Dammeroen’s shop; the three portraits in Meijeringh’s shop were most likely family heirlooms (one portrait of a deceased brother and two old “contrefeitsels”), whereas Doeck’s shop contained not a single portrait. Doeck’s private possessions, however, inventoried separately, contained three portraits, of which one was listed as “Een contrefeytsel van Corn. Doeck, sittende te schilderen,” most probably a self-portrait. The absence of portraits in the shops is noteworthy. Affordable portraits of well-known figures were mass-produced for the free market in major workshops in the seventeenth century, of which the so-called portrait factory of Michiel van Mierevelt (1566–1641) is a well-known example.38 Also in households the portrait genre seems to have remained popular throughout the seventeenth century.39

The third and most significant conclusion from Table 2 is, however, that the most important category for these three art dealers was unmistakably history painting (in all inventories over 40 percent) as opposed to landscape. One would have expected that art dealers targeting the lower end of the art market would have focused on selling landscapes and marines, because they could be produced rather cheaply by using labor-saving methods, such as a reduced color palette and the “wet-in-wet” technique in one layer of paint.40 The division of paintings into categories shows us that these three art dealers, Dammeroen, Doeck, and Meijeringh, were clearly specialized in selling affordable history paintings.

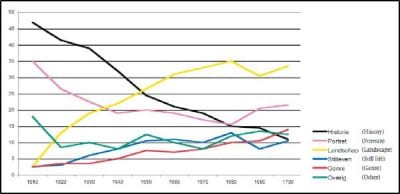

Furthermore, the high percentage of history paintings in these art dealer supplies of 1646, 1667, and 1687 contrasts strongly with our current understanding of the development of the ownership of different genres of paintings in the Dutch Republic. Graph 1, made by Marten Jan Bok and composed of household inventories in seven Dutch cities (Amsterdam, Delft, Dordrecht, Haarlem, Den Bosch, Leeuwarden, Leiden), illustrates that the relative dominance of history painting (the black line) decreased rapidly and continuously in the course of the seventeenth century. In 1610 over 45 percent of paintings in inventories belonged to the category of history painting, whereas in 1700 just a little over 10 percent did. By 1645 landscape painting (the yellow line) became the dominant category in households.41 The art market expanded significantly in the course of the seventeenth century: millions of paintings were produced, the ownership of paintings per household in the Dutch Republic more than doubled between 1620 and 1660, and due to product innovations and changes in taste a variety of new genres emerged. It is therefore an expected result that the relative weight of history painting in terms of ownership, as opposed to new genres, would have decreased. However, in sheer numbers the overall ownership of history painting increased as well.

Previous research in inventories may have sketched a biased picture of the actual ownership of paintings in the Dutch Republic, because the inventories were often only selected when containing at least one painter’s name.42 In a lesser-cited article of 1991, John Michael Montias made a distinction within a large sample of Amsterdam inventories between inventories with only unattributed paintings (generally the less wealthy estates) and inventories with one or more attributions to painters (generally the more wealthy estates).43 Over the period 1650–79, in the inventories with attributions, 14.4 percent of the listed works were history paintings and 31.4 percent were landscapes. The inventories without attributions, however, show a much less distinct difference: 18.4 percent history painting and 21.5 percent landscape. This suggests that in less affluent households history paintings were more common than in more wealthy households.44 Current study has, in fact, confirmed that small estates of lesser value contain relatively more history painting as opposed to the larger and more valuable estates. It could be concluded that almost all inventories contain at least one history painting, which seems to have been the first type of painting anyone sought to buy. Extra money available for the purchase of paintings in wealthier households was translated into the acquisition of more variety in terms of painting genres.45

Analysis of Stock-in-Trade: Subject Matter

Although history painting was the most prestigious category of painting according to contemporary art literature, the three art dealer inventories studied here show that this genre was also well represented in the lower segment of the Dutch art market. History painting seems to have been available to a broad spectrum of the public. Exploring the kinds of subjects that were represented may give us some insight into why art dealers active at the cheaper end of the art market focused on selling history paintings. For my analysis I divided the history paintings into six categories: Old Testament, New Testament, mythology, allegory, and “other.” This last category is composed of minor categories lacking a significant number of paintings. Paintings without reference to a specific subject (een historij) are brought together in the category “unknown/unspecified.” The results are listed in Table 3.

| Table 3: History paintings included in the inventories of Dammeroen, Doeck, and Meijeringh, divided by subject categories |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dammeroen (1646) | Doeck (1667) | Meijeringh (1687) |

||||

| number | % | number | % | number | % |

|

| Old Testament | 47 | 53% | 94 | 39% | 83 | 42% |

| New Testament | 20 | 23% | 46 | 19% | 35 | 18% |

| Mythology | 3 | 3% | 18 | 7% | 13 | 7% |

| Allegory | 12 | 14% | 15 | 6% | 9 | 5% |

| Other | 4 | 5% | 6 | 2% | 3 | 2% |

| Unknown/unspecified | 2 | 2% | 67 | 27% | 56 | 28% |

| Total # of history paintings | 88 | 100% | 246 | 100% | 200 | 100% |

| Source: SAA 5072, inv. no. 572, fol. 163–69, 21-09-1646; SAA 5075, inv. no. 2733, fol. 473–79, 13-07-1667; SAA 5075, inv. no. 2414, 20/25-06-1687. |

||||||

Table 3 shows that all three inventories are dominated by history painting with religious subjects, mostly taken from the Old Testament. The high concentration of subjects from the Old Testament seems to reflect the preferences of a Protestant audience.46 However, it contrasts with recent research performed by Frauke Laarmann on history painting in Amsterdam.47 Using all inventories in the Montias-Frick Database, Laarmann established that New Testament subjects, especially depictions with Mary as protagonist, were the most frequently represented historia in Amsterdam households during the period 1597–1681. Except for one Nativity in Dammeroen’s shop, three depictions of the Nativity and two of the Holy Family in the stock of Doeck’s shop, and a Nativity and two depictions of the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary in the shop of Meijeringh, subjects with Mary as protagonist are not represented in these dealer inventories. The discrepancy between the subjects of paintings in contemporary ownership and in stock of our three dealers remains a question to be explored by future research. It might imply that many of the paintings with Mary as protagonist in Amsterdam inventories were from an earlier period and inherited by the owners. Although more common in less wealthy households, Old Testament subjects do not seem to occur in great numbers in contemporary inventories. An alternative possibility is that Dammeroen, Doeck, and Meijeringh may have targeted a specialized group of art buyers in Amsterdam, or beyond. The latter would mean that this type of art dealer, with an enormous stocks of cheap paintings, targeted export markets in the way their Antwerp counterparts shipped thousands of devotional pictures across Europe and Spanish America throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.48

The emphasis of these cheap dealer stocks on history paintings with religious subjects can be explained by the recognizable and marketable character of biblical narratives. First, in the seventeenth century most biblical stories were common knowledge at all levels of society, in contrast with mythological subjects or complicated allegories. That portrayals of such stories from the Bible were widely popular is also suggested by the countless objects of everyday use decorated with biblical narratives that surrounded the people in their homes, such as cabinets, cradles, pottery, and tobacco boxes.49 The few mythological subjects, such as Diana Bathing, represented in these dealer stocks were also accessible and appealing to a broad public. The listed allegories all depict the recognizable theme of the Five Senses. The dealers had no paintings in stock that could potentially be considered so complicated that they would deter possible buyers.

| Table 4: Subjects of history painting that are listed four or more times in the inventories of Dammeroen, Doeck, and Meijeringh | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of times specific scene listed | Dammeroen (1646) | ||

| 5 | The marriage of Jacob and Rachel | ||

| 4 | Abraham and Hagar | ||

| 4 | Jephthah* | ||

| 4 | Annunciation of Christ’s birth to the shepherds | ||

| Doeck (1667) | |||

| 5 | Annunciation of Christ’s birth to the shepherds | ||

| 5 | Jephthah’s daughter is sacrificed | ||

| 5 | Susanna and the elders | ||

| 4 | Diana bathing | ||

| 4 | Mary, Joseph and the newborn Christ | ||

| 4 | The discovery of Moses | ||

| 4 | The meeting of Jacob and Joseph | ||

| 4 | The raising of Lazarus | ||

| Meijeringh (1687) | |||

| 7 | Joseph’s brothers selling him for twenty pieces of silver | ||

| 6 | The gathering of manna | ||

| 5 | Joseph discovers his silver cup in Benjamin’s sack | ||

| 5 | The meeting of Jacob and Joseph | ||

| 5 | The angel Raphael disappears in front of Tobias | ||

| 4 | Pharaoh and his army engulfed in the Red Sea | ||

| 4 | Jeroboam offers a sacrifice to the golden calf | ||

| Source: SAA 5072, inv. no. 572, fol. 163–69, 21-09-1646; SAA 5075, inv. no. 2733, fol. 473–79, 13-07-1667; SAA 5075, inv. no. 2414, 20/25-06-1687. * The paintings listed as “Jephthah” presumably depict the same scene as those specified “ Jephthah’s daughter is sacrificed,” which is also represented five times in the stock of Doeck. |

|||

Secondly, apart from having a religious meaning, this type of history painting was attractive because of its storytelling character. We therefore need to take a closer look at the subject matter. The specific scenes in the stock of Dammeroen, Doeck, and Meijeringh that occur four or more times are listed in Table 4. Some of these repeatedly represented subjects are highly entertaining and dramatic. For example, the story of Jephthah and his daughter, which ends with Jephthah sacrificing his daughter, was represented four and five times, respectively, in the shops of Dammeroen and Doeck (Table 4). This subject was appealing because of the gruesome story, regardless of the quality of the work. This is highly contrary to such subjects as domestic interior scenes of everyday life, which derived their appeal primarily from the finesse and skillfulness with which the artist painted figures and interiors and were, therefore, more expensive. This may explain why genre paintings are barely present in the shops of these art dealers who targeted a lower segment of the art market (Table 2).

Cutting Production Costs

The inexpensive paintings that Dammeroen, Doeck, and Meijeringh sold differ from other known mass-produced works of art, such as the anonymous production of thousands of devotional paintings after established models during the first decades of the sixteenth century in the Southern Netherlands or the anonymous workshop copies or imitations that originated in most seventeenth-century master studios.50 The three Amsterdam art dealers sold their paintings as “originals” and under the name of the artist. The question remains how the art dealers managed to sell these “original” history paintings for such low prices.

Dutch artists generally favored a traditional artisanal system for the calculation of prices and used an hourly or a daily rate to set their prices.51 The workshop notebook of the prominent portrait and history painter Adriaen van der Werff shows that he charged a basic rate of 25 guilders a day for his labor and added additional costs (such as the frame, packing material, and transportation costs) to determine the minimum price of a painting.52 Other known rates from master painters vary from 3 guilders a day to Gerrit Dou’s outrageous 6 guilders per hour.53 The relative price of the hourly rate of a painter was dependent on his reputation (talent, experience, status). The sum of hours spent on the painting mostly reflected its size but also the painter’s technique and rate of productivity. For example, Eric Jan Sluijter proposed that while Jan van Goyen and Cornelis van Poelenburch, who both had a considerable reputation during their lifetimes, charged a more or less similar rate of 8 to 10 guilders a day, Van Goyen used a rapid technique to produce more paintings faster and, as a result, could sell his paintings relatively cheaply (approximately 10 guilders for a small painting, 60 for a large one); Van Poelenburch on the other hand used a finer, more labor-intensive technique, with which he worked ten times longer on a single painting of similar size and, as a result, also asked prices that were ten times as high.54

At the top end of the market—with such high rates as 25 guilders a day or 6 guilders an hour—labor was the determining factor in calculating the asking price of a painting, making the investment in materials relatively low.55 However, the businesses of Dammeroen, Doeck, and Meijeringh had paintings in stock made by artists with little or no reputation. In general labor was cheap: a usual wage for a skilled laborer was around 1 guilder a day. As a result, at this end of the art market, the investments in material and additional costs must have been relatively important components of the price.

The emphasis of these shops on contemporary and local artists suggests that the art dealers were mostly active in the firsthand market. A few exceptions show that the dealers also had contacts with painters commanding large workshops in cities where overproduction occurred, such as the 31 paintings Doeck owned that were made by pupils and assistants of the Haarlem history painter Jacob Willemsz. de Wet,56 and the paintings Meijeringh owned by the Rotterdam painter Jan Gabrielsz. Sonjé, his pupils, and other painters from his direct network.57 Moreover, the statement that these art dealers were primarily active on the firsthand market is not without exception. The archival document that registered Meijeringh and two of his colleagues as buyers at the auction of Doeck’s estate demonstrates that large sales of paintings were important venues for art dealers in obtaining paintings for resale, just as they are today.

| Table 5: The five most frequently cited painters in the inventories of Doeck and Meijeringh | |

|---|---|

| Doeck (1667) | Number of works listed per painter |

| Leendert de Laeff | 64 |

| Roelof and Michiel de Vries* | 34 |

| “De Fuyter” [unidentified] | 25 |

| Willem Dalens | 15 |

| Pieter Wiggersz. | 12 |

| Total number of paintings by the five most frequently cited painters | 152 |

| Total number of attributed paintings | 284 |

| Share of five most frequently cited painters | 54% |

| Meijeringh (1687) | |

| Barend Jansz. Slordt | 69 |

| Michiel Carré | 14 |

| Adriaen Gael | 11 |

| Gijsbert Cruijsbergh | 10 |

| Dionijs Verburgh | 10 |

| Total number of paintings by the five most frequently cited painters | 114 |

| Total number of attributed paintings | 252 |

| Share of five most frequently cited painters | 45% |

| Source: SAA 5075, inv. no. 2733, fol. 473–79, 13-07-1667; SAA 5075, inv. no. 2414, 20/25-06-1687. * The inventory of Doeck’s stock was drawn up quite sloppily. The names “Vervries,” “Reynier de Vries,”“R. Vervries,” and “M. Vervries.” all appear. It is most likely that all but the last of these refer to Roelof Jansz. van Vries. However, in this table all paintings designated by these names are considered as coming from one workshop. |

|

The high number of paintings by specific artists listed in Table 5, such as the 64 paintings by De Laeff and the 69 paintings by Slordt in the stock of Doeck and Meijeringh, respectively, and the fact that the five most frequently cited artists were responsible for 45 percent of the total number of attributed works, together with the unpainted supports and painters’ equipment present in their shops, strongly suggest that in-house production was the most important channel in obtaining paintings. For example, of the 69 paintings by Slordt in Meijeringh’s inventory, 53 were history paintings. This number constitutes more than one fourth of all the history paintings in stock in the shop, demonstrating that the business relied to a substantial extent on the production of this one employee. The other subjects include landscapes, sea battles, and banquets. Slordt seems to have painted everything that the art dealer thought the public demanded or that his stock was lacking. The appearance of painters’ equipment in the inventory of Dammeroen’s shop implies that he, too, contracted painters for in-house production. For the high end of the Amsterdam market, this practice is known from Hendrick and Gerrit Uylenburgh (father and son), who contracted top painters such as Rembrandt, Govert Flinck, and Gerard de Lairesse to make portraits on commission and originals for the free market, and in addition engaged young painters to copy the famous Italian, Flemish, and French paintings present in the shop.58

Nothing is known about De Laeff except for eight signed paintings surviving today and one notarial deed dated 1661 that shows him living in the Amsterdam Beulingstraat.59 And, until recently, nothing about Slordt was known either. With an oeuvre today of only one signed painting, Slordt was (and is) certainly a painter without reputation. Archival research only very recently brought to light a few documents about his life.60 He was born in the city of Medemblik in the province of North Holland, started his career as an iron seller, and switched to painting only after moving to Hoorn in 1661, where he painted for a local female art dealer. It is unknown where, when, and with whom he received a painter’s training. In 1675 he moved to the village of Schermerhorn, which was approximately 40 kilometers from Amsterdam and in the seventeenth century easily reachable by water transport in a couple of hours.

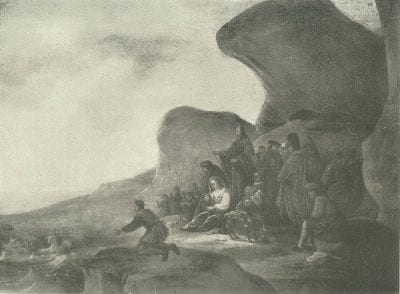

Officially, Slordt was a resident of Schermerhorn (he never registered as residing in Amsterdam), but he must have worked and lived for one or more short periods in Meijeringh’s workshop. This becomes plausible after comparing Slordt’s single known signed work, Pharaoh and His Army Engulfed in the Red Sea (fig. 2), with a painting by Adriaen Gael of the same subject (fig. 3). The Meijeringh inventory lists a painting of this subject by Gael in the attic workshop, where, together with other paintings and the Bible illustrations of Matthäus Merian, it functioned as a model for his employees. Remarkably, nearly all the history paintings present in Meijeringh’s attic were made by pupils and assistants of the prolific Haarlem history painter Jacob Willemsz. de Wet.61 The comparable depiction of some specific human figures and their poses in both paintings and the fact that this painting was present in the workshop demonstrates that the staffage in Slordt’s painting is unmistakably based on the prototype by Gael.62 The comparison between the paintings of Gael and Slordt shows that the latter did not copy Gael literally but merely painted a simplified version of this composition, presumably in order to enhance the speed of production.

While it is most probable that Slordt had access to this type of painting in Meijeringh’s shop, it is unlikely that he first drew after the painting, then transported his drawings to Schermerhorn to work them up into paintings there, then have to transport more than 70 paintings back to Amsterdam. As a general rule, when dealers contracted with painters, the dealer provided the materials; thus, the art dealer could control the quality of the material as well as the costs.63 The amount of painter’s equipment in Meijeringh’s workshop, including more than 50 panels and canvases and three painter’s easels, also offers further evidence that Meijeringh maintained an active workshop as well as a dealership.

The employment of painters provided art dealers with the highest degree of control over production costs. Slordt presumably worked and lived in Meijeringh’s attic for a few months, then returned to his family in Schermerhorn after payment. Because of his lack of reputation, the cost of his labor was cheap. The costs of living were lower in small villages than in the city, and Slordt’s rate was probably even lower than that of painters of similar reputation residing in Amsterdam. In addition, as an inhabitant of Schermerhorn the painter was excluded from the jurisdiction of the Amsterdam guild, so that guild regulations did not apply to him.

As argued previously, the low hourly rates of painters without reputation left the material and additional expenses as a substantial part of the total cost of a painting. The amount of paint needed for a square meter of support is hard to calculate and depended on technique, but the majority of pigments were not extremely expensive and, in addition, were for sale in various price brackets. In-house production offered the art dealers some sort of supervision over the amount of paint and the kind of pigments used by their employees. The painting support, however, was the largest expense. In this regard it is remarkable that the art dealers all showed a preference for the use of panel instead of canvas supports. This suggests that panel, contrary to what one may expect, was the cheaper option. An example of prices of supports can be obtained from the inventory of Rotterdam painter’s equipment seller Jacob Abrahamsz van Koperen (1680), which shows panels in ten standard sizes, with prices varying from half a stuiver for the smallest panel to 22 stuiver (1 guilder and 2 stuiver) for the largest panel. One canvas, regrettably of unspecified size, was valued at 16 stuiver.64 The large differences in prices between the various panel-sizes show how in this inexpensive section of the market the price of a painting was dependent on its size, primarily because of material costs. The stock of painting supports in the art dealers’ inventories suggests bulk commissions to panel and canvas makers, and perhaps the provision of a volume discount.65 Moreover, standard sizes facilitated mass production.

In addition to the possibility of controlling material costs, the dealers employing painters could influence both the artist’s technique and working methods. It also allowed attuning production to recent fluctuations in demand, which in theory resulted in an up-to-date supply. The fact that despite many possible subjects, more than one and in some cases up to seven paintings in one dealer’s stock depict the same scene (Table 4) suggests that such control took place in the shops of these art dealers. The works listed in the inventory as painted by Slordt are summarized in Table 6 and demonstrate that he often painted multiple versions of a scene for Meijeringh in different standard sizes and in horizontal as well as in vertical format. For example, Meijeringh owned three versions by Slordt of Joseph discovering his silver cup in Benjamin’s sack, in two different sizes, in horizontal and vertical format. Of other subjects, such as Joseph being sold by his brothers, and the Gathering of Manna, Meijeringh owned as many as six versions by Slordt, both in four different sizes.

| Table 6: Paintings by Barend Jansz. Slordt with scenes that are listed two or more times (including the number of different standard sizes in which they appear) in the inventory of Meijeringh (1687) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of times specific scene listed | Number of sizes listed | |||

| 21 | 3 | History [unspecified] | ||

| 9 | 2 | Landscape with animals | ||

| 6 | 4 | Joseph being sold by his brothers | ||

| 6 | 4 | The gathering of manna | ||

| 5 | 4 | Sea battle | ||

| 3 | 2 | Joseph discovers his silver cup in Benjamin’s sack | ||

| 2 | 1 | “Banketje” [Still life of a meal] | ||

| 2 | 2 | Pharaoh and his army engulfed in the Red Sea | ||

| 2 | 2 | The people dance around the golden calf | ||

| 2 | 2 | Christ blessing children | ||

| Source: SAA 5075, inv. no. 2414, 20/25-06-1687. | ||||

The existence of multiple paintings depicting the same scenes does not merely imply that the production of multiples was prompted by current demand and that these were popular and often requested scenes. Rather, along with the use of standard support sizes, it demonstrates that techniques and methods for serial production were in use to produce more paintings in less time. This amounted to a reduction in labor costs—paintings “that are a dime a dozen” in the words of Samuel van Hoogstraten.66 A comparison of the single known work signed by Slordt, dated 1680, and an almost identical but unsigned version of this scene, presently in the Edams Museum (fig. 4), highlights some of these methods. The signed panel is larger than the unsigned panel and reveals more landscape on all sides of the composition, yet the staffage is almost identical and of exactly the same size. The unsigned panel does not show traces of cropping and its measurements are original. The similar size of the human figures suggests that for both paintings the same template was used—for the larger piece the background landscape was simply extended in all four directions. This standardized mode of production recalls fifteenth-century commercial workshops, in which a limited number of well-chosen compositions with a simplified design was endlessly repeated in standard sizes with the use of patterns and models.

The comparison of the two paintings demonstrates that exactly the same depictions were produced in different sizes, as has already been made clear from the inventory of Meijeringh. Attributing the unsigned work to Slordt is somewhat problematic because of some differences in execution. Such differences may be explained by former restorations. Yet it is also possible that another employee of Meijeringh’s shop painted this depiction using the same template.67 A closer look at the Edams painting confirms the expected economizing on material and labor expenses. The oak support is relatively thin, the light-colored ground was thinly applied and reveals the grain of the wood, the background landscape is plain, painted in one layer of paint and with the “wet-in-wet” technique, and the human figures are painted with only a limited number of bright colors, which were applied in a thin layer of paint directly on the ground. With an efficient use of support and paint, costs were cut on the quantity of the materials used, rather than on their quality.

Conclusion

The insights gained by analyzing these three dealers’ inventories demonstrate that the state of current research on the production of painting in the Dutch Golden Age is incomplete. It also shows the pitfalls of focusing on the oeuvres of painters with a high reputation and on the ownership of paintings as apparent in samples from wealthy households and the more upscale probate inventories. This approach has presented us with a historically incorrect image of the paintings circulating in the seventeenth-century art market. As this study has shown, there existed a large market for cheap history paintings, traded by art dealers with enormous stocks of over 500 paintings, with an average estimated value of 4 guilders and less, at least some of whom specialized in religious, mostly Old Testament subjects. The low-quality paintings, mainly executed by painters with little or no reputation, were appealing because of their subjects; biblical narratives, with an emphasis on violent and spectacular scenes, were apparently recognizable and attractive for a broad audience.

In the primary market, prices for paintings were calculated by multiplying the hourly rate of a specific painter by the time spent on labor and adding additional costs for the materials. The history paintings in the stock of Dammeroen, Doeck, and Meijeringh could be sold cheaply by regulating production costs. The art dealers employed painters without reputation, such as Barend Jansz. Slordt, and therefore could pay low hourly rates for in-house production. Employing painters directly made it possible to adjust production to current demand. Material costs were kept low by an efficient use of the materials, rather than saving on quality. Painters’ levels of productivity were kept high by money-saving techniques and mass-production working methods, such as the use of templates, standard sizes, and reproducing the same composition in different sizes and formats. Cheap on spec-production of depictions that were in demand, and therefore easily marketable, signified limited financial risks for the art dealers.

The comparison of the two paintings of Pharaoh and His Army Engulfed in the Red Sea, one signed by Slordt and one unsigned, demonstrates that this type of production fundamentally differs from the cheap workshop copies and imitations that also flooded the seventeenth-century art market. Although the standardized mode of production and the repetition of the central motif recalls fifteenth-century commercial workshops, this type of serial production was, surprisingly, often not anonymous. In contrast with Antwerp mass production or the anonymous assistants of painters, a few surviving panels demonstrate that works by such painters as De Laeff and Slordt were signed with the name of the artist. Less wealthy art buyers in the second half of the seventeenth century could therefore, in a time in which authenticity of a painting became more and more important, acquire an original work of art, albeit one signed by a painter without a high reputation. The mainly religious subject matter of these paintings lacked complicated or obscure iconography and could therefore be appealing to a myriad of buyers.

Although this study has contributed to a new understanding of the low-end market, further questions arise. Additional research by the author, conducted as part of a dissertation, will address the motivation of the painters for involvement in this type of production. First results have already shown that these painters’ social and financial backgrounds differed significantly from those of the more successful painters, who enjoyed greater opportunities for education, training, and social networking. Moreover, the expanded scope of the dissertation will allow exploration of the question of an export option for this type of work.