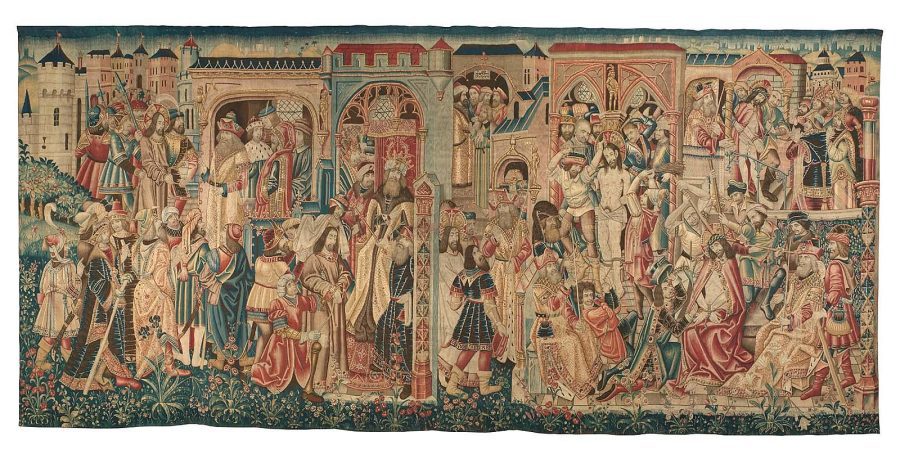

The Passion of Christ in Jerusalem (ca. 1500; Museu Nacional do Azulejo) weaves an episodic account of Christ’s Passion through a unified Jerusalem cityscape. Previous scholars have classified it as a northern import, a work by a Netherlandish artist commissioned as a gift for Queen Dona Leonor of Portugal by Emperor Maximilian I. Material evidence, however, suggests that it was produced in Portugal and that the artist modified and assimilated Netherlandish iconographies, combining them with Portuguese cultural references, to create a unique work shaped by and for the audience it served: the Poor Clare nuns of the Madre de Deus convent outside of Lisbon. The Lisbon Passion is a hybrid work that synthesizes a range of visual inspirations and adds to the hybridization of the convent itself, bridging Lisbon and Jerusalem.

Introduction

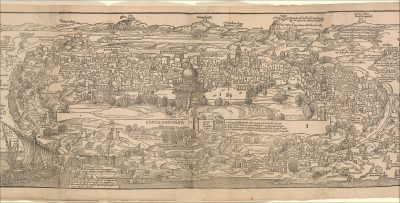

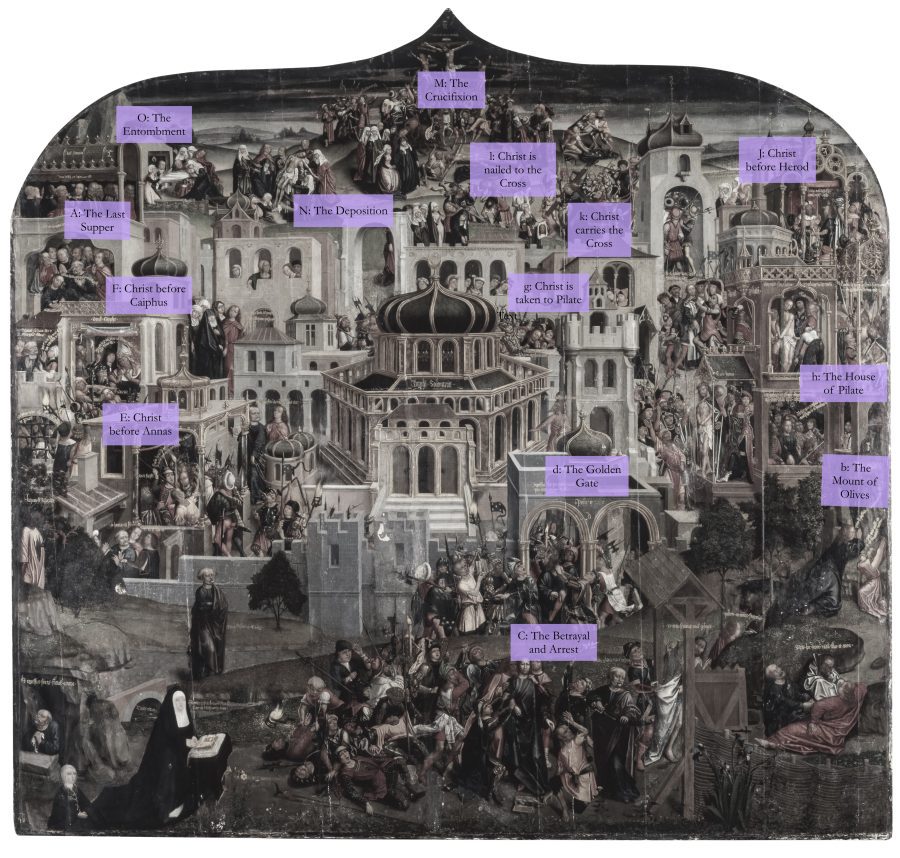

The monumental panel known as The Passion of Christ in Jerusalem weaves an episodic account of Christ’s Passion into a unified cityscape of Jerusalem (fig. 1). Previous scholars have classified it as a Netherlandish work, lauded for its presumed familiarity with the work of Hans Memling (ca. 1430–1494) and prized for being a gift from Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519) to his cousin, Dona Leonor of Portugal (1458–1525), who presented it to the Poor Clare Convent of Madre de Deus, outside of Lisbon.1 A reassessment of the panel’s construction and recorded provenance, however, suggests that the Lisbon Passion panel was made in Portugal rather than the Netherlands. Reorienting the panel’s production location allows for a more nuanced examination of its distinctive imagery and its role in the community it served. The Lisbon Passion clearly draws on Netherlandish artistic traditions, but the work is more complex than a pastiche of various northern iconographies. It adapts and creatively combines northern and Portuguese imagery, visualizing the cultural encounters and entanglements that defined late medieval and Renaissance Europe.2 The panel’s distinctive imagery reflects and responds to the socio-religious concerns of its original audience, the Madre de Deus nuns, as well as the panel’s likely patron, Dona Leonor.

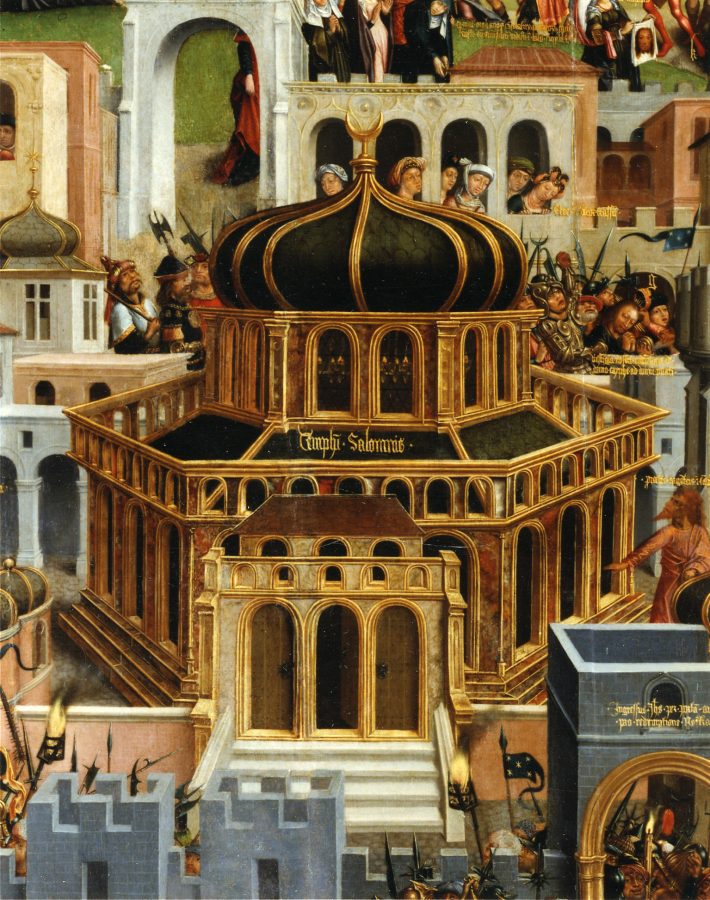

In the panel, Christ takes a circuitous route through Jerusalem. The story unfolds in a continuous narrative through a panoramic cityscape, beginning with the Last Supper and ending with the Entombment. Surprisingly, the composition’s focal point is not Christ but the Temple, rendered as the Dome of the Rock, which Christians believed to be built over the remnants of the Temple of Solomon.3 Christ’s meandering path is guided by sequential Latin lettering and Scripture excerpts that guide the viewer through the busy composition (fig. 2).4 Two votaries are depicted in the lower left corner. The larger and more visually prominent is Dona Leonor, queen consort and later queen dowager of Portugal, who had founded the convent in 1509 and participated in the community as a tertiary nun and a generous patron. Dona Leonor is depicted kneeling in prayer before a prie-dieu (a prayer desk for devotional use), wearing a white wimple beneath a black veil, the monastic habit of a sister of the Poor Clares. The gold text issuing from her mouth reads: “Remember, Lord, thy maidservant and save your servant for your redemption.”5 An unidentified female companion behind her is truncated at the waist. Dona Leonor and her companion observe but do not participate in the events that unfold in front of them. Despite occupying the same continuous landscape, they are separated from the action that animates it.

This article’s reorientation of the panel’s production from the Netherlands to Portugal does not negate the inspiration of Netherlandish artistic expression on the panel as a whole. Rather, it demonstrates that Netherlandish imagery was integrated into Portuguese artistic production in ways that went beyond stylistic mimicry. The unusual rendering of the Temple as the Dome of the Rock, crowned with a crescent-moon finial, is an artistic innovation on the part of the artist, one that would have resonated especially strongly with a Portuguese audience charged with a Crusading mentality borne of the recently completed reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula and the ongoing conquest campaigns in northern Africa. The panel’s use as a visual stimulant for Passion devotion as well as a physical marker for the Via Crucis—a devotional retracing of the Stations of the Cross, or Christ’s route from his sentencing to his Crucifixion—within the convent walls allowed the nuns to participate in a metonymic Holy Land pilgrimage. As such, the panel contributed to the hybridization of geographic space within the convent, bridging Lisbon and Jerusalem.

In this light, the Lisbon Passion can be viewed as a hybrid work, or, more accurately, a product of hybridization. Viewing it as such allows for a fuller appreciation of the interconnected Portuguese cultural context to which the panel both belonged and responded. In this way, the Lisbon Passion challenges the traditional art historical canon that has relegated Iberian cultural production to Europe’s periphery.6 Simultaneously, it enables us to respond to the reasonable concerns that arise when the term “hybridity” is only applied in colonial contexts, thereby, as Carolyn Dean and Dana Liebsohn put it, “homegeniz[ing] things European and set[ting] them in opposition to similarly homogenized non-European conventions.”7 Specifically, this painting allows us to expand the application of the “hybrid” model to demonstrate that Renaissance Europe was also a hybrid place.8

Perceived and Real Origins: From the Netherlands to Portugal

Previous scholars have classified and regarded the Lisbon Passion as a South Netherlandish import to Portugal based on a misunderstanding of the panel’s materiality and recorded provenance.9 Indeed, the panel’s construction corresponds to Portuguese rather than Netherlandish production practices. Furthermore, the Habsburg provenance associated with the work appears to be an eighteenth-century invention, contradicting earlier sources and obscuring Dona Leonor’s role in commissioning the work.

Throughout Europe, panels for painting were constructed at local carpentry workshops, operating in conjunction with but independently from the artists’ workshops; we would therefore expect them to exhibit methods of construction local to the place of manufacture rather than those of the artist’s country of origin. Jacqueline Marette’s influential research on European frames and supports established that oak was by far the most common support in the northern and southern Netherlands in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, while poplar was most common in Italy and both poplar and pine in Spain.10 The Lisbon panel is made of oak, seemingly placing it within the tradition of Netherlandish panel making. However, Portugal’s forestation was unique in southern Europe in that indigenous oak grew along its Atlantic coast.11 Furthermore, Portugal is known to have imported large quantities of Baltic oak from northern Europe via sea trade, and both local and imported oak were used in Portuguese panel production.12 This is supported by dendrochronological studies: The Saint Vincent Retable, created by Nuno Gonçalves (ca. 1425–1491; Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga) for the altar of the Lisbon Cathedral in 1469, is made of imported Baltic oak,13 as are the Life and Passion of Christ panels at the Charola (private oratorium) of the Convent of Christ in Tomar, attributed to Jorge Afonso.14 The oak of the Lisbon Passion has not been dendrochronologically examined, but if it is made of either local or Baltic oak it could have been crafted in a Portuguese workshop. This material interchange speaks to Renaissance Europe’s interconnected landscape.

Two elements that have thus far gone unnoticed distinguish the Lisbon Passion from contemporaneous panel construction in the Netherlands and associate it with Portuguese workshop production. The first is the substantial thickness of its planks. At three centimeters, the boards are cut significantly thicker than was customary in Netherlandish and German works of the time, which ranged between one half and a centimeter and a half thick.15 Portuguese panels, on the other hand, were frequently significantly thicker, ranging between two and four centimeters in thickness, often more than double that of their Netherlandish counterparts.16 This is evident in the Charola panels in Tomar, where the Entrance of Christ into Jerusalem is 3.7 centimeters thick.17 The thickness of the Lisbon Passion’s oak support, therefore, corresponds more closely to Portuguese than Netherlandish workshop practices.

The Lisbon painting’s joinery method, which consists of internal splines locked by perpendicular dowels (fig. 3), also distinguishes it from panels made in Netherlandish workshops. Hélène Verougstraete, in her comprehensive study of Netherlandish frames and supports, shows that the vast majority of Southern Netherlandish panel paintings were butt-joined, a method in which joins are secured by dowels or splines inserted into the width of the panel. Splines locked by dowels inserted perpendicularly to the panel’s surface, meanwhile, were used only exceptionally. They do appear in works by Hugo van der Goes, most notably perhaps his Death of the Virgin (fig. 4), The Adoration of the Shepherds (ca. 1480; Gemäldegalerie Berlin), and the Portinari Altarpiece (1475; Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence). However, this latter joinery method was very rarely used in northern panel paintings, appearing only in Hugo’s works and three other documented cases.18 Internal splines locked by perpendicular dowels were, in other words, the exception rather than the rule in Netherlandish production.

Joinery methods in Portugal, however, depart from the Netherlandish model. Filipa Raposo Cordeiro has surveyed the joinery methods found in Portugal and found that Portuguese panels were most commonly butt-joined and secured by cylindrical dowels or splines inserted in the panel’s edges.19 She also notes that splines locked by perpendicular dowels also appear occasionally and hypothesizes that this joinery system was “commonly used . . . in Flemish workshops that might have influenced Portuguese practices.”20 However, as mentioned above, this method was exceptionally rare in the Netherlands. In fact, Portugal appears to be the only European region with a significant concentration of paintings using this joinery system.21 Among the Portuguese panels made with this joinery method are Jorge Afonso’s panels of The Life and Passion of Christ (fig. 5);22 Saint Sebastian and Saint Vincent (ca. 1520; Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga), attributed to a follower of Frey Carlos; and Vasco Fernandes’s Calvary (ca. 1520; Museu Grão Vasco), all dating from around the same period as the Lisbon panel. While this joinery method may have been adapted from an atypical Netherlandish method, by the time the Lisbon Passion was created it was far more customary in Portuguese workshop practices than in their Netherlandish counterparts.

The construction methods used in the Lisbon Passion strongly suggest that the painting was made in Portugal. Additional technical research, particularly ground layer analysis, could shed further light on the panel’s production process. The ground layer materials used in panel paintings can help to locate production, with calcium carbonate (CaCO3) typically indicating northern manufacture and calcium sulphate (CaSO4) typically indicating southern manufacture. That said, while calcium sulphate is the most commonly used ground layer in Portugal, calcium carbonate is also used on occasion, presumably imported from northern Europe, indicating that this well-established material dichotomy may be less binary in Portugal.23 That both methods and materials could sometimes transcend regional origins and assimilate into Portuguese production processes demonstrates how geopolitically and materially interconnected Portugal was at the time.

Locating the material production of the Lisbon Passion in Portugal contradicts the traditional claim of its northern origin, and similar problems attend conventional thinking about the painting’s Habsburg provenance. According to that provenance, first put forward by Portuguese historian Frei de Belém, Emperor Maximilian I commissioned and gifted the panel to Dona Leonor, and this has been accepted and perpetuated somewhat uncritically. However, a reassessment of the documentary sources concerning the panel’s patronage undermines the authority and validity of this narrative, restoring Dona Leonor as the panel’s most likely patron.

In his Cronica Serafica (1755), Frei de Belém credits Maximilian with gifting the “singular” retable of “the city of Jerusalem, perfectly painted, with all the episodes of the Passion” to his cousin Rainha Dona Leonor, “along with the relic of Saint Auta” (see fig. 1).24 An earlier seventeenth-century account by the Madre de Deus nuns, meanwhile, credits Maximilian with gifts to the convent but emphasizes Dona Leonor’s role in gifting the panel, stating that: “Her [Dona Leonor’s] virtue is shown to us in the text that she had affixed next to her portrait that she left us in the altarpiece of Jerusalem, which says: ‘Memento Domine ancillae tuae et servae servorum tuorum ob redemptionem tuam’” (Remember, Lord, thy maidservant and save your servant out of your redemption).25 An earlier account, meanwhile, does not link the Lisbon panel to Maximilian at all. In his Crónica do Felicissimo rei Dom Emanuel (1566), Damião de Góis credits Maximilian with bestowing on Dona Leonor “some relics of those saint virgins, which he easily accorded” (the relics of Saint Auta, one of the eleven thousand virgins accompanying Saint Ursula) but makes no mention of the Lisbon Passion panel.26

Given that the panel’s construction appears to be Portuguese, and given that early sources emphasize the role of Dona Leonor, rather than the emperor, with gifting the panel to the convent—a scenario supported by the panel’s inclusion of her portrait— it appears likely that she, rather than Maximilian, was the patron of the work. Perhaps the Habsburg provenance was an eighteenth-century invention by Belém, inspired by the painting’s ambiguously Netherlandish stylistic references, and at a time when association with the Holy Roman Emperor may have offered an aura of prestige. Either way, the persistence of this provenance has hampered appreciation of Portuguese agency—in this case, Dona Leonor’s—reflected in the creation and meaning of the work. The result has reinforced a center-periphery paradigm in which such a singular work as the Lisbon Passion must have been created in the Netherlands, the perceived center, and gifted to Portugal, the presumed periphery. By relocating the production and patronage of the Lisbon Passion to Portugal, a more nuanced analysis of the painting is possible, one that sees the work as a rich amalgamation of diverse sources adapted in the service of its audience-oriented content.

Adapting Netherlandish and Portuguese Imagery

Scholars have emphasized the Lisbon Passion’s reliance on northern sources in its imagery, particularly Hans Memling’s Scenes from the Passion of Christ in Turin (fig. 6) and the View of Jerusalem woodcut in Bernhard von Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio in Terram Sancta (fig. 7). However, if the Lisbon Passion was created in Portugal at the request of a Portuguese patron, assertions that “the artist of the panel was almost certainly familiar with” Hans Memling’s Turin Passion become less persuasive.27 While the Lisbon Passion shares a continuous narrative structure with certain works by Hans Memling and others, careful examination reveals that the mode of operation was more likely adaptation rather than imitation. Motifs from Breydenbach are similarly reinterpreted rather than replicated. Rather than identifying specific northern influences on the panel, we should consider the Lisbon panel as a work that synthesized a diverse range of imagery, both northern and Portuguese, to create an object that reflected the tastes and concerns of its Portuguese audience.

Memling was born in the Rhineland and moved to Bruges after working at Rogier van der Weyden’s (ca. 1399–1464) studio in Brussels. Although famously dismissed by Panofsky as a “major-minor master,” Memling wielded considerable influence in his lifetime. He received commissions not only from local patrons but also from individuals and institutions in England, Spain, and Italy.28 He created works in the continuous narrative format later used in the Lisbon Passion and is credited with the most sophisticated renderings of this narrative type, as seen in his Turin Scenes from the Passion of Christ and Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ (fig. 8).29 Max J. Friedländer’s observation that “Memling’s narrative flows, in gentle waves, towards the blissful goal of redemption and transfiguration” can be appreciated in the Turin and Munich panels despite the busyness of the compositions.30 Nevertheless, there are no direct quotations of Memling in the Lisbon Passion, raising the question of how directly any of Memling’s compositions influenced it.

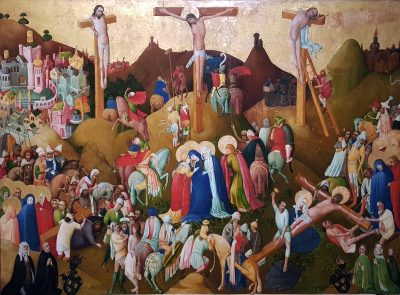

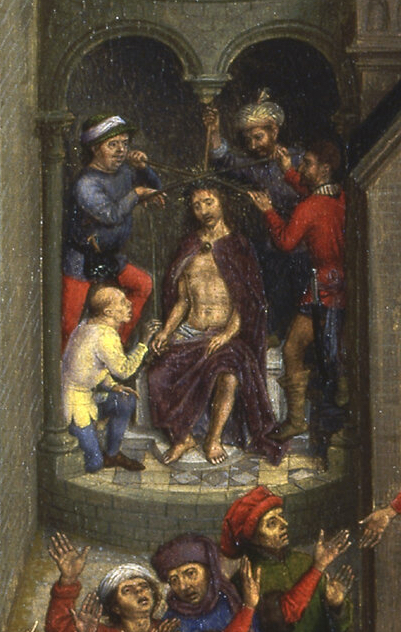

Both the Lisbon and the Turin panels depict Christ’s Passion in a unified cityscape in which architecture is integral to the compositional and narrative structuring of Christ’s Passion. But the events depicted, as well as the surroundings in which they unfold, differ between the two works. The narrative sequence of the Lisbon Passion runs from the Last Supper to the Lamentation, while the Turin Passion runs from Christ taking leave from his mother and Mary Magdalene to Christ on the road to Emmaus. While both compositions are set within unified cityscapes, the cities are vastly different. The Lisbon scenes are clearly set in Jerusalem, evident in the prominence of the Temple of Solomon (in the recognizable form of the Dome of the Rock) and the orientalizing domed structures that flank it. Memling, on the other hand, brings the Holy Land to Flanders, enhancing gabled brick buildings with exoticizing touches. The Flagellation of Christ is the focal point of the Turin composition, whereas the Temple of Solomon commands center stage in the Lisbon panel. The Lisbon Passion, rather than reproducing Memling’s composition, is thus unique in terms of narrative and structural framework. Any familiarity the artist had with Memling appears to have been adapted creatively rather than borrowed wholesale. The Lisbon panel’s independence from Memling is made clearer in comparison with a sixteenth-century copy after Memling’s Passion, believed to have been made in southern Europe, which faithfully replicates Memling’s original composition (see fig. 6),31might be better illustrated with the Memling copy (see fig. 18).

Notably, Memling was neither the creator nor the sole proponent of this continuous narrative structuring, and it most likely grew out of an older visual tradition that was not limited to the Netherlands. Other examples include The Passion of Christ (fig. 9), The Wasservass Calvary (fig. 10), and The Passion of Christ (ca. 1480; Kościół św. Jakuba), all by unidentified artists.32 These examples, like the Lisbon Passion, are all single panels that present the events of Christ’s Passion within a unified landscape. Despite sharing a common narrative structure, the panels are all stylistically distinct and represent different series of episodes set in various landscapes. Tapestries, too, provided a visual precedent for depicting the Passion in a continuous narrative form, such as the Netherlandish Christ Before Pilate and Herod (fig. 11) or the Franco-Flemish tapestry series of the Passion now at the Museo de Tapices de La Seo (ca. 1410–1425). Panels and tapestries both use architectural structures to organize narrative in a similar way to the Lisbon panel. Given the broad availability of both the continuous narrative format and the strategies artists used to convey it, it seems reasonable to suggest that Memling need not have been a source, either direct or indirect, for the Portuguese workshop that produced the Lisbon Passion, which could just as readily have turned to alternative sources such as these.

Indeed, it may well have done, for the Lisbon Passion also departs stylistically from Memling. While the panel’s style is reminiscent of Netherlandish artistry in its precise handling of paint, integration of narrative in landscape, and the verisimilitude with which the plants in the foreground are represented, it lacks the Turin Passion’s soft contouring of figures, adept foreshortening, and convincing spatial recession. Neither does the Lisbon artist modulate light and dark as deftly as Memling, who uses it in the Turin panel to distinguish night from day and thus the unfolding of time. Characters are also depicted differently in the two artists’ work. While the soldiers’ facial expressions and gestures in the Lisbon Passion are exaggerated to the point of caricature, the emotional responses of those present in the Turin panel are more subtly rendered (figs. 12 and 13, respectively).

The Lisbon panel is more stylistically similar to paintings produced in Portuguese workshops during the period, albeit workshops that were exposed to Netherlandish artistic styles, whether directly or indirectly. The stylized posing and stark highlighting of Christ in the Garden of Olives in the Lisbon Passion can be compared, for example, to the rendering of the same episode in the earlier Triptych of Santa Clara (fig. 14 ). Parallels can also be found in the physical representation and placid expression of Christ under arrest in the Altarpiece of the Chancel of Viseu Cathedral (1501–1506; Museu Nacional Grão Vasco), attributed to Francisco Henriques and Vasco Fernandes.

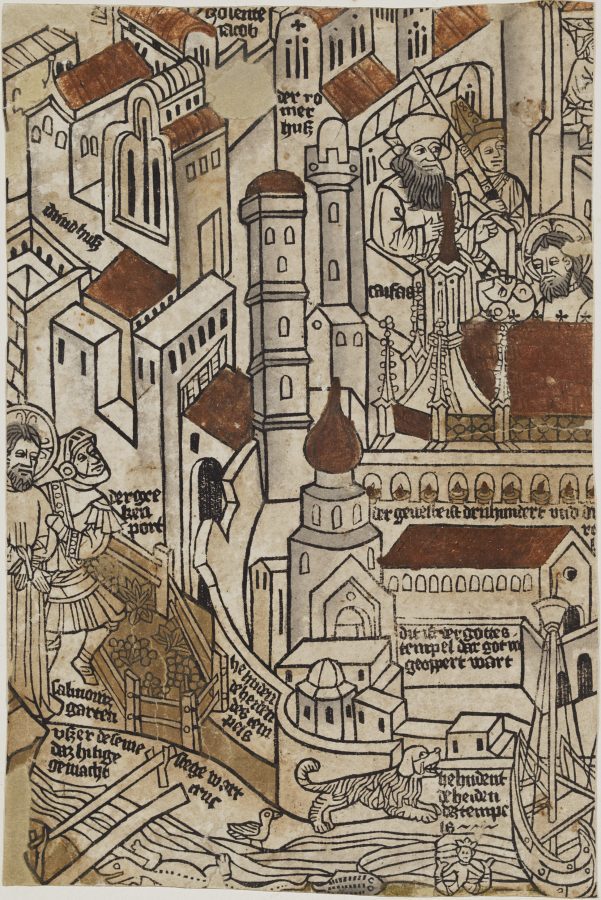

Arguments in favor of the “northernness” of the Lisbon Passion further stem from the resemblance of the painting’s architectural framework to a woodcut in Bernhard von Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio in Terram Sancta (1486).33 The Peregrinatio is a Jerusalem travel guide based on Breydenbach’s own 1483 journey to the Holy Land.34 The book was illustrated by Erhard Rewich (1445–1505), an artist who accompanied Breydenbach on his pilgrimage, with fold-out maps depicting various sections of the journey. Rewich’s woodcut of the City of Jerusalem was the most topographically accurate rendering of Jerusalem in the West at the time, and the Lisbon panel borrows the print’s general architectural framework, particularly its rendition of the Dome of the Rock and the Golden Gate (see fig. 7). But the Lisbon Passion does not directly copy the Rewich woodcut. Many of the specific buildings surrounding the Temple are missing or altered, and while the Lisbon panel is populated by Christ and his followers and adversaries, the Rewich image is populated by figures dressed in contemporary fifteenth-century attire. What we find in the Breydenbach print is not the Passion of Christ but the city of Jerusalem as encountered by pilgrims in the fifteenth century. In contrast, the Lisbon panel adapts the imagery to transpose events and people of Christ’s Passion to contemporary Jerusalem, thus combining architectural elements borrowed from Breydenbach with a Christological setting and a continuous narrative format.

The Lisbon Passion’s adaption of Breydenbach imagery could, and most likely did, occur in Portugal. Prints and printed books circulated widely throughout Europe in the last decades of the fifteenth century, since they were relatively inexpensive to produce and easy to transport.35 Because of the inherent mobility of prints, an artist could come across images produced at great geographic distance from their original area of production. The Breydenbach guide was immensely popular throughout Europe; it was reprinted numerous times and translated into Spanish in 1498. There are copies of the book in the Portuguese royal library, copies to which Dona Leonor most likely had access.36

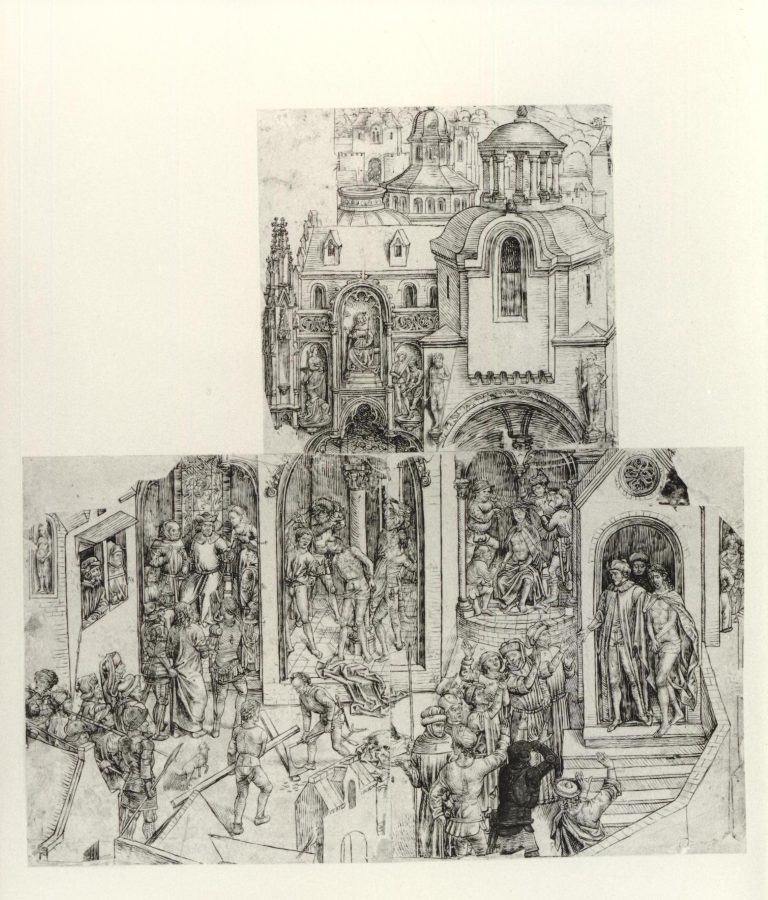

The Lisbon artist may also have drawn from other printed sources. Two sheets depicting Christ’s Passion in Dartmouth, the only remnants of what was most likely a twelve-folio print, combine Jerusalem’s architecture and the Passion narrative in a manner similar to the Lisbon Passion (figs. 15 and 16).37 Each woodcut is approximately 17.8 centimeters wide by 28 centimeters high, and the entire work would have measured approximately 1.20 by 1.12 meters, which is more than half the size of the Lisbon panel. The fragments were discovered pasted into the binding of Hartmann Schedel’s Liber Chronicarum, which was printed in Nuremberg by Anton Koberger in 1493. The Dartmouth sheets, like the Lisbon panel, depict scenes from Christ’s Passion taking place in Jerusalem. Landmarks such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre or the Temple of Solomon are labeled (this time in German, rather than Latin), though the depicted structures are less faithful evocations of Jerusalem’s architecture than those seen in the Breydenbach woodcut and the Lisbon Passion. André Jammes and Henri Dominique Saffrey have suggested that the sheets were pasted together and displayed publicly, possibly on the walls of a monastery or church.38 The Lisbon Passion, as discussed below, most likely performed a similar role in the Madre de Deus convent. The Dartmouth fragments, as well as the much larger—if now lost—complete work from which they came, are similar in size, format, and function to the Lisbon Passion. It is possible that another, similar woodcut assemblage also inspired the artist of the Lisbon panel, one that borrowed the architectural framework of the Breydenbach View of Jerusalem. Fragments of a drawing after Memling’s Turin Passion (ca. 1520–1540) survive (fig. 17), and it is possible that other graphic interpretations of Memling’s compositions, now lost, also circulated in Portugal at the time. The circulation of works fostered transculturation and likely contributed to the creative synthesis of the geographically disparate imagery evident in the Lisbon Passion.

Regardless of the specific iconographies that may have inspired the artist of the Lisbon Passion, numerous alterations observed in both the underdrawing and paint layer indicate that the painting’s final appearance resulted from creative problem-solving.39 The Lisbon artist was not mechanically copying or transferring the composition from a single source but rather adapting elements of other imagery while also incorporating his own innovations during the production process. This kind of adaptation and incorporation required a grasp not only of specific motifs but also of how those motifs might interact in previously unknown combinations. Such unique combinations occurred in Portugal in part because Portuguese artists regularly traveled to other artistic centers, and imagery and artists from those centers also readily found their way there. The anonymous artist of the Lisbon Passion could have encountered numerous examples of northern art in southern Europe: prints traveled widely, and the Saragossa tapestries and the Williams copy of Memling’s Turin Passion (fig. 18) show that northern exemplars of continuous narrative were both imported and copied in southern Europe. Similarly, a Portuguese artist may have traveled to northern Europe for training, as Eduardo o Português (active 1504–1506) is recorded to have done, and thus have become acquainted with Netherlandish imagery and style, which then imbued their work upon their return to Portugal.40 A northern artist may also have relocated to Portugal, as a number did, where they adopted certain characteristics local to Portugal.41 Whatever the mechanism, the critical point to recognize is that artists actively and thoughtfully adapted, modified, and augmented what they encountered from other visual traditions.

By focusing on identifying the panel’s supposed northern models, scholars have overlooked the local context and visual culture that also shaped the painting’s imagery. The visual entanglements found in The Passion of Christ in Jerusalem (see fig. 1), both northern and Portuguese, demonstrate its hybridity. Indeed, the creative arrangement of certain features in the Lisbon Passion reflect the specific Portuguese sociopolitical context in which it was created . The Temple in the Lisbon panel, for example, boasts a small but significant change to Breydenbach’s woodcut: a crescent moon finial atop the Temple (fig. 19). The crescent moon, used as an Islamic symbol since at least the thirteenth century, held particular resonance in early modern Portugal.42 By incorporating a crescent moon atop the Temple, the artist depicted Christ’s Passion in neither the historical Jerusalem of Christ nor a heavenly Jerusalem, but rather in Jerusalem as encountered by contemporaneous pilgrims. In contemporaneous Jerusalem, access to sites of Christological significance was restricted or mediated by Islamic rule. Jurisdiction over the actual Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem was a source of great political-religious contention at the time, and the crescent in the panel probably alluded to this ongoing conflict.

When Crusaders conquered Jerusalem in 1099, they converted the Dome of the Rock into a church, the Templum Domini. They affixed a golden cross atop the Dome as a finial, erected an altar over the rock, hung images of Christ and the Virgin inside, and affixed Latin inscriptions both internally and externally, thus Christianizing what was at the time a Muslim holy site.43 However, the Dome’s Christianization was brief. When the sultan Saladin retook Jerusalem in 1187, he stripped the Dome of all Christian iconography, restoring the structure to a Muslim space. Medieval Christian pilgrims to Jerusalem commented on and lamented the insertion of a crescent finial atop the Dome of the Rock. In the text of his guide, Breydenbach describes it as “an eclipsed moon, which marks it as a Muslim house of worship”, though it is not included in the accompanying image.44 The substitution of a crescent moon for the cross atop the Dome in Jerusalem in the Lisbon Passion thus represents the political reality of its day: the loss of Christian Jerusalem to Islam.

The crescent moon is not typically depicted in Christian images of the Temple. Contemporaneous Western Passion imagery tended to depict the Temple as a domed structure, but one that lacked a crescent finial. In other words, the domed representation of the Judeo-Christian Temple in Passion imagery became separated from the actual contemporaneous, crescent-topped Muslim structure of Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock.45 The Temple is depicted in a circular and domed form in a Netherlandish Christ Bearing the Cross (fig. 20), Jan van Eyck’s The Three Marys at the Tomb (ca. 1410–1426; Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen), and the Breydenbach print. But none of these domed temples include a crescent moon. Thus, we find in the Lisbon Passion a crucial distinguishing characteristic: the emphasis placed on the Dome of the Rock and the inclusion of a crescent moon finial atop it, evoking the state of religious conflict very much on the minds of contemporaneous Portuguese viewers.

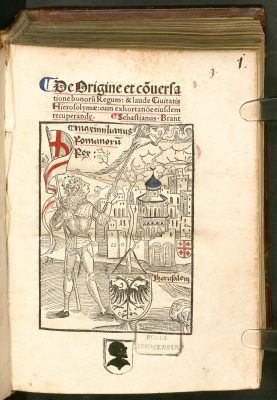

While further research is yet to be done, the crescent moon does appear in Western imagery of the period on rare occasions, usually in the context of pilgrimage or Crusading imagery. The crescent appears, for example, in Sebastian Brant’s (1458–1521) “Emperor Maximilian Approaching Jerusalem,” in De origine et conversatione bonorum regum et de laude civitatis Hierosolymae (fig. 21);46 Jan Le Tavenier’s “View of Jerusalem,” in Burchard of Mount Sion’s Description de la Terre Sainte (1455); and Michael Wolgemut’s “Destruction of Jerusalem,” in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493). These images do not depict scenes from the Passion, though. Rather, they are Jerusalem cityscapes that illustrate pilgrimage guides or Holy Land histories. All of the accompanying texts contain explicit or implicit calls to Crusade. Though working in a different historical register, the artist of the Lisbon Passion nonetheless imbues his image with this Crusading mentality by joining the crescent moon with the template of the Dome of the Rock translated from Breydenbach’s guide.

The synthesis of various iconographies in the Lisbon panel constitutes the residue of additional, localized meaning. The crescent’s association with Islam would have struck a particularly strong chord with a Portuguese audience. In Iberia, where Christian leaders battled Islamic rule from 711 until 1492, Christian resentment of Islamic presence proliferated. While Portugal had become Christian by 1249, Muslims were not officially expelled from the peninsula until Ferdinand and Isabella’s victory in Granada in 1492, quickly followed by their expulsion of the Jews. In 1496, Manuel I of Portugal instituted a similar policy of religious persecution, ordering that “all the Jews and free Muslims residing within Our realms, whatever their age, must leave on pain of death and of losing all their property in favor of those who would accuse them.”47

Manuel’s religious ambitions combined the expulsion of all non-Christians from Portugal with dreams of Crusade and conquest.48 These were initially aimed at Morocco, which he wished to incorporate into Portugal’s dominions. In 1496, he obtained two bulls from Pope Alexander VI in support of a North African Crusade. The first, Redemptor noster, granted a plenary indulgence to those who fought to conquer Morocco or contributed financially to the campaign. The second, Cogimus jubente, promised to finance Manuel’s Crusade using the proceeds from two years’ worth of Church tithes collected in Portugal. Manuel campaigned for a new Crusade to recapture the Holy Land in 1506, but his plan was never carried out. Nonetheless, the prevalence of Crusading sentiment in Portugal during this period suggests that the representation of the Temple of Solomon as the Dome of the Rock in the Lisbon Passion, complete with a crescent moon finial, would have resonated particularly strongly with this audience.

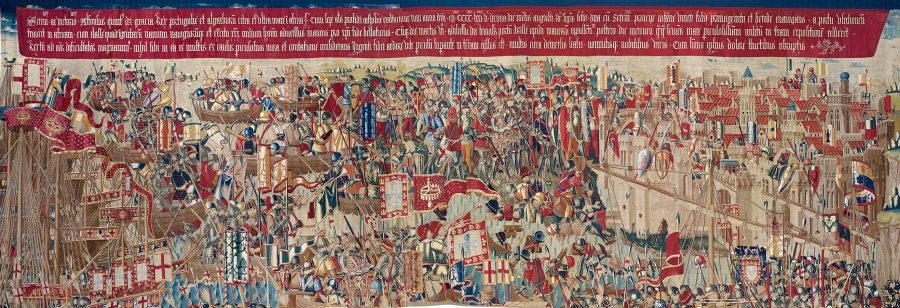

Indeed, despite its rarity in late medieval Passion imagery, the crescent moon as a symbol of Islam was part of the Portuguese visual vernacular in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. For example, the motif can be found in The Conquest of Asilah and Tangier, a set of four tapestries commissioned by King Afonso V of Portugal from the Tournai workshop of Passchier Grenier (1447–1493) to commemorate the Portuguese conquest of the eponymous cities in 1471 (late fifteenth century; Museo Parroquial de Tapices de Pastrana).49 In the tapestry representing the landing at Asilah, made by and for a Christian audience, the city is swarmed by Portuguese soldiers wielding banners bearing the arms of Portugal, the Order of Christ, and the Order of Saint Catherine, while Moroccan forces defending the city bear banners decorated with crescent moons and scorpions (fig. 22). Here, contemporaneous battles over territorial rule are depicted as a clash of symbols, with banners bearing Christian Europe’s arms set off against those associated with Islam.

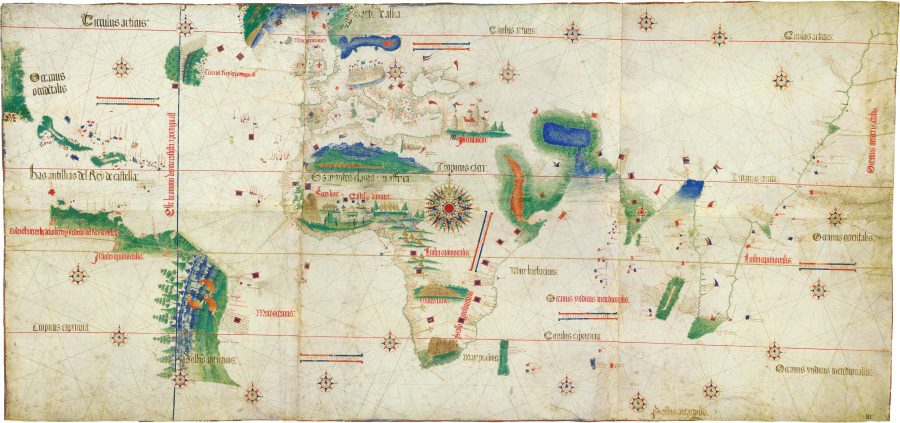

The crescent moon also appears in a number of Portuguese portolan charts (navigational charts) and atlases from the time period, including the Miller Atlas (1519), a world atlas commissioned by Manuel I from Lopo Homem and Pedro and Jorge Reinel, with illuminations by António de Holanda (1580–1571) (fig. 23). The atlas depicts territorial campaigns waged by Christian and Islamic powers through the clash of symbols on the seas: ships sailing under flags bearing the cross of the Order of Christ compete with Islamic ships flying flags emblazoned with a crescent moon. At times, such charts used symbols to show a combined political reality (Islamic Jerusalem) and biblical narrative (Christian Jerusalem). The Cantino Planisphere (ca. 1502), which some believe is a copy of the now-lost Portuguese Padrão Real, for instance, depicts Jerusalem with three crescent moon flags flying atop the city’s buildings to indicate that the city was under Islamic rule (fig. 24). At the same time, the single Crusader cross painted atop the Holy City’s tallest building deviates from geopolitical reality and expresses Christianity’s sense of entitlement to the city. In a portolan chart by Jorge de Aguiar (d. 1508) (1492; Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library), Jerusalem is also marked both by a black dot, used by the cartographer to designate territories under Islamic rule, and by crosses, conveying the city’s Christological significance.

Operating in a similar manner, the Lisbon panel combines geopolitical reality and eschatological symbolism. The crescent moon atop the Temple of Solomon/Dome of the Rock indicates that the Holy City, the site of Christ’s Passion, remains under Islamic rule. Meanwhile, the crucified Christ, hovering over the subjugated temple, implicitly reminds early modern viewers both of Christ’s sacrifice and the fact that the sites of his Passion were not under Christian rule. In complex iconographical cases such as this, the Islamic crescent moon would have held strong Crusading connotations for contemporaneous Portuguese audiences.

The artist who created the Lisbon Passion borrowed and adapted a wide range of imagery, both Netherlandish and Portuguese, inventively.50 They did so in order to conflate the Passion of Christ with a Crusading mentality that pervaded Iberia at the time. The Lisbon Passion’s visual hybridity was thus shaped both by and for its Iberian context. In its creative adaption of various motifs and visual strategies, it poses a challenge to the conventional categorization of objects based on tidily circumscribed national or regional stylistic schools. Objects, motifs, and even artists circulated between the Netherlands and Portugal during this period, contributing to robust artistic cross-fertilization and hybridization.51

The Passion of Christ in Jerusalem Panel in its Portuguese Context

By reconsidering the Lisbon Passion as a hybrid work made in Portugal, we can more thoughtfully question how the panel appealed to, and was encountered by, its intended audience: cloistered Portuguese women. First, recall that the aforementioned seventeenth-century nun’s chronicle, lauds the work as “the retable of Jerusalem given to us by Dona Leonor” and makes no mentions of its artistic style or origins. It appears that the panel was appreciated above all for its content, regardless of what viewers perceived to be its regional stylistic associations. It thus worthwhile to consider how the panel’s imagery reflected the cultural environment in which it was created. In addition to its associations with the Portuguese Crusade against Islam, the Lisbon panel, by visually articulating the sites of Christ’s Passion, offered a model of pilgrimage that engaged with devotional perambulations performed in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Portugal, both inside and outside of the convent.

The Portuguese were interested in the Holy Land not only for Crusading purposes; there were also efforts to transpose the loca sancta (Holy Land) to Portugal, a task the Lisbon panel visually accomplishes. Such efforts were part of a widespread increase in Holy Land devotion seen throughout late medieval Europe, evidenced by the proliferation of pilgrim guidebooks, the pursuit and acquisition of Jerusalem relics, the expansion of the Stations of the Cross, and the construction of Jerusalem architectural complexes across Europe.52 Jerusalem complexes, also known as Holy Land replicas, recapitulated the infrastructure of the Via Crucis, allowing devotees to participate locally in the kinetic experience of Jerusalem pilgrimage.

The architectural settings of the Passion panel (fig. 1a) relate to such Jerusalem complexes implemented in Iberia, where the Portuguese devotion to the loca sancta is well documented. We know, for example, that a Portuguese factor accompanied Breydenbach on his pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1489 and that the Hieronymite Antonio de Lisboa traveled from Portugal to the Holy Land in 1507, meticulously recording the measurements of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the distances between the stations of the Via Crucis.53 Such firsthand accounts, both textual and visual, transmitted the forms and measurements of these holy sites back to Iberia, inspiring and informing the local construction of Jerusalem complexes and reconstructions of the Via Crucis. The first Holy Land replicas in Iberia appeared along the pilgrim route to Santiago de Compostela as early as the last decades of the eleventh century, when Spanish and Portuguese architects erected Jerusalem complexes in the Catalan towns of Tallada and Palera, the Arogonese city of Zaragoza (the convents of the Carmen and of the Canonesses of the Holy Sepulchre), the Navarrese towns of Eunate (the Iglesia de Santa María) and Torres del Río, and the old Castilian cities of Valladolid and Segovia.54 Visitors to a complex, like pilgrims to the Holy Land, would move from one site associated with Christ’s life or Passion to another, reflecting on the events that occurred there and praying in supplication. Holy Landscape replicas, in some cases, were even granted the privilege of bestowing indulgences equivalent to those available at the corresponding sites in Jerusalem, making them as worthwhile a demonstration of piety as a pilgrimage to the Holy Land itself. This was the case for the Catalan Holy Sepulchre in Palera, which received permission to issue plenary indulgences in 1085, as well as the Madre de Deus convent, as discussed below.55

The architecture of the Holy Land was also purposefully replicated in Portugal. The octagonal structure of the Charola of Tomar, originally a Templar stronghold, was inspired by the architecture of the Dome of the Rock. In a similar vein, the painter Francisco de Holanda (1517–1584) proposed in 1571 that the Church of Saint Sebastian in Lisbon be built in the shape of the Anastasis (the Church of the Holy Sepulchre), demonstrating that Jerusalem’s architecture was admired in Portugal well into the sixteenth century.56 As these examples indicate, participation in Jerusalem pilgrimage substitutes became an expected feature of Iberian devotional expression, providing a stage on which would-be pilgrims could enact their pious journeys locally.

Architecture is essential in the Lisbon Passion, just as it was in Jerusalem complexes, for structuring the participants’ devotional experiences. In addition to the pictorial sources discussed above, such physical models may well have inspired the architectural imagery of the Lisbon panel. The devotional structuring of Jerusalem complexes is translated into a two-dimensional plane in the Lisbon Passion, transforming a metonymic pilgrimage into an ocular one. Viewers of the panel could shift their gaze from site to site, from episode to episode, in the same way that visitors could walk through Holy Land replicas, reflecting on the corresponding sites in Jerusalem and the events that occurred there. In the Lisbon panel, the incorporation of biblical texts and location labels also helped guide and prompt its users’ devotional exercises. Moreover, the panel’s inclusion of the same indulgenced prayers recited on actual Jerusalem pilgrimages, such as the prayer to Saint Veronica, suggests the Lisbon Passion served as a pilgrimage substitute for its Portuguese audience, providing an opportunity for obtaining indulgences that was analogous to an actual Jerusalem pilgrimage.

The Jerusalem complexes in Iberia, like the Lisbon Passion, carried a layer of meaning not found in their counterparts elsewhere in Europe: specifically, efforts at a Christian reconquest of the Peninsula. In the context of early sixteenth-century religious conflict, building Jerusalem complexes in Iberia became a means of re-Christianizing land and spaces thought to have been desacralized by Muslim occupation.57 Such replicas were both substitutes for actual Holy Land pilgrimages and physical manifestations of the Iberian Peninsula’s successful conquest and Christianization; as such, their evocations were both Christological and contemporaneous. The Lisbon Passion’s emphasis on the architecture of Jerusalem was thus tailored to its late medieval Iberian audience, for whom pilgrimage was a political and religious assertion as well as an act of devotion. The Lisbon panel’s visual synthesis articulates the multilayered associations of religious geography in medieval and Renaissance Iberia.

Jerusalem within the Convent: The Reception of the Passion within Madre de Deus Convent

While the Lisbon Passion (fig. 1b) reflects the larger Portuguese cultural context in which it was created, it is also important to consider how the panel would have reflected and been received by its intended, more localized audience: the cloistered Portuguese Poor Clare nuns of the Madre de Deus Convent, as well as Dona Leonor herself. The Passion panel reflected and supplemented that cloistered community’s specific devotional practices, and its imagery was shaped by and for this audience.

The Poor Clare convent Madre de Deus in Xabregas, founded by Dona Leonor in 1509, adhered so strictly to the enclosure rules that the Portuguese historian Duarte Nunes de Leão commented that “in the convent of Madre de Deus . . . the discalced nuns (one might almost call them walled-in nuns) can never leave for whatever reason.”58 Dona Leonor entered the Madre de Deus convent as a tertiary nun and was therefore not as closely bound by the rules of enclosure as her sister nuns were. The latter would have been prohibited from participating in pilgrimages and thus forced to develop devotional alternatives. One such devotional alternative can be seen in the Lisbon Passion panel. If Jerusalem complexes translated Holy Land pilgrimage experiences to local geographies, then the Lisbon Passion can be said to transpose the sacred topography encountered on Holy Land pilgrimages to within the convent walls.

The Lisbon panel, with its panoramic format and detailed imagery, would have served as a powerful stimulant for mental pilgrimage, allowing Dona Leonor and her fellow sisters to travel metaphorically through both space and time, first by transporting them to the city of Jerusalem and, second, by returning them to Christ’s time and casting them as witnesses to the Passion. The former was accomplished through the verisimilitude of its architecture, while the latter was accomplished through the rich visual narration of the events. The panel had the potential to be a valuable aid in “virtual pilgrimage,” a concept Kathryn Rudy has fruitfully considered in the context of Northern European art, though her analysis does not extend to the panel’s situation within a Portuguese context.59

In the seventeenth-century account of the convent, the nun Metildes describes her amazement at how many “steps” (or “stations”) are represented in the panel “between the Supper and the Sepulchre,” indicating that users of the panel were mentally tracing the route of the Passion.60 A nineteenth-century copy of the same seventeenth-century account refers to the “retable of Jerusalem” as a station marker in a Via Crucis enacted within the cloister walls, supporting the proposal that it was used as an aid in a virtual pilgrimage. In the account, the abbess explains:

The community perambulates through the verandas and in the cloister, chapter and dormitory, pacing everywhere, sometimes first starting in the choir near the Retable of Jerusalem where the House of Pilate is painted and the Lord leaving it with the Cross, the second stop in the chapter is at a retable representing the meeting with the Virgin Mary, the third in the verandas in a niche that has the panel of Simao Sireneo [Simon of Cyrene] helping to carry the cross for Christ our redeemer, the fourth and fifth in the cloister in the two niches of the daughters of Jerusalem and Veronica, the sixth in the choir at the altar of Jesus crucified, these stations the community walks every Friday in Lent.61

According to the abbess, the topographical route of Christ’s Passion was superimposed on the architectural footprint of the convent, fusing the sisters’ perambulations with the associative Holy Land sites encountered by actual pilgrims to Jerusalem.62 As a result, The Passion of Christ in Jerusalem both visually simulated Jerusalem’s topography and physically marked the sisters’ reenactment of the Via Crucis within the convent.

This was not just a spiritual exercise for the Poor Clare nuns, but one for which they could earn indulgences. In 1511, at the bequest of Dona Leonor, Pope Julius issued a bull allowing the Madre de Deus convent to grant indulgences for participating in a virtual pilgrimage.63 The Lisbon Passion was thus not only a tool for Passion devotion but also a genuine pilgrimage substitute, connecting Madre de Deus and Jerusalem through its unique imagery and reception.64 As a result, it aided in the hybridization of the convent’s geographic space by superimposing Jerusalem on Xabregas.

Dona Leonor: Pilgrimage and Patronage

The distinct imagery of the Lisbon Passion reflected the devotional-political climate of fifteenth-century Portugal while also playing a more localized role in the spiritual life of the Madre de Deus community. The work, however, would have spoken most directly to the panel’s donor and likely patron, the Portuguese dowager queen, Dona Leonor. Dona Leonor was one of late medieval Portugal’s most powerful women and also one of its wealthiest. She received a base annual maintenance stipend of 1.165 million reais, which was secured by Lisbon rents and supplemented by income from various territories included in the Casa da Rainha (queen’s household and estate).65 She was thus endowed with the resources and position to be a significant patron of the arts, and her patronage included architectural structures and artworks commissioned both locally, from Portuguese workshops, and internationally, from artists in Italy and the Netherlands.66 Thus, while the Lisbon panel has been considered in terms of Maximilian’s presumed gifting and as to how it pertains to Dona Leonor’s Clarissan devotion, it is worth assessing the possibility that Dona Lenor was the donor of the work in light of her broader patronage, especially in its orientation toward the loca sancta.67

Dona Leonor’s extensive patronage reveals a Christological and Holy Land focus beyond the Madre de Deus convent. While such interests were not unusual at the time, they do put her patronage of the Lisbon panel in context. In its ambiguous authorship, Holy Land associations, and inclusion of visual references to Dona Leonor, a finely wrought Holy Cross reliquary commissioned by Dona Leonor offers parallels to the Lisbon panel (fig. 25). The piece has been variously attributed to a Flemish, German, or Portuguese artist based in Lisbon, demonstrating how ambiguous modern distinctions between artistic schools can be.68 Dona Leonor’s emblem (a shrimping net) and the Portuguese royal arms, minutely rendered in enamel, adorn the reliquary’s columns and base, not only associating her with its commission but also with the Crucifixion (as represented both by the reliquary itself and by the cross relic it contains). The inclusion of Dona Leonor’s portrait in the Lisbon panel similarly links her to Christ. Dona Leonor’s patronage of The Passion of Christ in Jerusalem and the Holy Cross reliquary combine both Passion imagery and self-promotion.

The imagery of the Lisbon Passion is more complex than that of the Holy Cross reliquary—or, for that matter, most Passion images. It is filled with scenes from Scripture as well as apocryphal episodes, such as Christ Encountering Veronica and The Crossing of the Cedron River, which feature in devotional literature such as Ludolph of Saxony’s Vita Christi and various pilgrim guides. The difficulty in following the complex narrative of the Lisbon panel indicates it was painted for an audience familiar with such sources and suggests that the imagery was created in close collaboration between patron and artist.

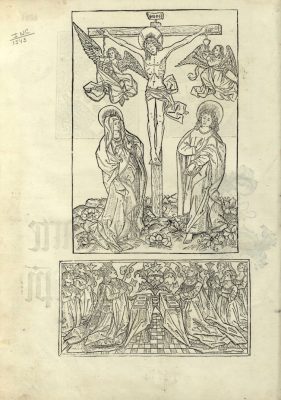

Recent research contends that worshippers in fifteenth-century Castile favored exegetical devotions that focused on Christ’s divinity over meditative texts that emphasized his humanity—but this was not the case in Portugal.69 In 1495 Dona Leonor commissioned a translation of the Vita Christi, one of the country’s first printing ventures.70 A woodcut of Dona Leonor and her late husband João II opens each volume of the Portuguese edition of the text (fig. 26). Interestingly, the two are shown praying before an image of the crucified Christ, an iconography appropriated from a print by Martin Schongauer, further demonstrating the adaptation of northern iconography to the devotional and representational needs of Portuguese patrons.

Dona Leonor also had guides such as Marco Polo’s and Bartholomeus Anglicus’s Proprietatibus Rerum (1519) in her library, and, as previously noted, two editions of Bernhard von Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam were recorded in the royal library. While it is unclear who owned them, Dona Leonor would at least have had access to them.71 These books not only recount the episodes of Christ’s Passion but also describe the physical sites where those episodes occurred. They also specify the prayers to be recited at each station, linking sacred episodes to sacred topography in the same way that the Lisbon panel does.

Dona Leonor actively sought out firsthand accounts of Jerusalem by financially sponsoring members of her court to go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and those accounts supplemented her other textual sources. Such efforts both confirmed her piety and served as a “surrogate” pilgrimage for which Dona Leonor was rewarded with the same indulgences as if she had traveled to the Holy Land herself. Such motivations may have compelled Dona Leonor to send to Jerusalem her confessor, the Franciscan Frei Afonso do Rio, who relayed his experiences in the Holy Land to the queen upon his return.72

These examples demonstrate Dona Leonor’s active interest in both the loca sancta and pilgrimage, as well as her concerted effort to become acquainted with the experience of Jerusalem pilgrimage from within the confines of Portugal. The Lisbon Passion of Christ in Jerusalem thus reflects Dona Leonor’s spiritual concerns while simultaneously requiring knowledge of the sources with which she was familiar in order to navigate its complex imagery successfully. This suggests that the Passion panel’s hybridity was a deliberate expression of the devotional orientation of its likely patron and the other members of the convent she sponsored.

Conclusion

Previous scholarship has viewed the Lisbon Passion of Christ in Jerusalem panel as a Netherlandish painting commissioned by Emperor Maximilian I and indebted to Memling (see figs. 6 and 8) and Breydenbach (see fig. 7). That view is limiting and has prevented an examination of how the panel reflects and participated in its Portuguese context. The panel’s construction strongly suggests that it was made in Portugal, rather than northern Europe. The panel also synthesizes various pictorial and textual sources that circulated throughout northern and southern Europe as well as the Iberian Peninsula. The painting reflects the transcultural context in which it was created, challenging strict art historical categorizations based on national stylistic schools.

The painting’s unusual emphasis on the Dome of the Rock, crowned with a crescent moon finial, reflects the distinctly Iberian confluence of Christ’s Passion, the Crusades, and the Reconquista of the Peninsula. The composition also reflects the cloistered Poor Clare community’s preference for loca sancta devotion by serving as a site for substitute pilgrimage, contributing to the convent’s melding of geographic and sacred space. Finally, the panel mirrors the specific spiritual concerns of its likely Portuguese donor, Rainha Dona Leonor of Portugal, in both form and function.

The Lisbon panel can thus be recast more accurately as a work created in Portugal by an artist of unknown origin. Various inspirations—both northern and Portuguese, two-dimensional and three-dimensional—were adapted to create a unique, hybrid work shaped by and for its cloistered Portuguese audience. The Passion of Christ in Jerusalem, in its iconographic and stylistic conflations, emphasizes that defining the object’s “origin” by the presence of specific iconographies or artistic styles does not accurately reflect the complex intersections and interactions that existed in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe and Renaissance Portugal.