The relation between the sublime and the comic has never been fully developed theoretically. In the European context laughter and the sublime would seem to be awkward partners. Yet in the work of Hals the two are brought together, provoking the question of how the sublime is related, formally and in terms of content, to happiness and the comic. It is possible on the basis of Hals’s work to define a distinctly Dutch baroque that prefigures the unfolding of key philosophical issues concerning the nature of history and the actualization of worlds.

Happiness, the Comedic, and the Sublime

In the work of Frans Hals (1582–1666), people are often shown laughing. Yet all these artfully, convincingly represented laughing people are not effective in making us laugh, as they do in works typically classed within the genre of the comic, or comical, in the context of which Hals’s laughing faces would have been “comic prompts.”1 But if these laughing figures are not comic prompts, what response were they intended to elicit? The answer to this question—and why it involves the sublime—can be sensed, and tested, by revisiting one of Hals’s more famous paintings: Young Man and Woman in an Inn, from 1623 (fig. 1; formerly known as Yonker Ramp and His Sweetheart).

Of late we have seen a shift in the scholarly analysis of works such as this: a turn away from a moralizing-didactic framework toward one that focuses on their festive or celebratory function. Such paintings were intended to affect the audience rather than teach it something, as Anna Tummer noted in a catalogue entitled The Golden Age Is Having a Party.2 The question then becomes, what exactly was their effect, also in terms of affect? The answer to that question is important because the scholarly attraction of the moralizing approach is that it can specify so easily, or so it seems, what paintings mean. Even in some of the studies that acknowledge the festive and celebratory character of seventeenth-century Dutch art, one can trace the powerful echo of what most nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholars would contend: that it always carried, even if ambiguously, a moralizing message. For instance, Barbara Haeger’s paradigmatic reading of Young Man and Woman in an Inn held that it does not depict the prodigal son, a contention brought forward by others, but carries the message that the world can be enjoyed only if we restrict our passions, avoid frivolous places and company, and shun especially the excessive use of alcohol.3 Likewise Gerline Lütke Notarp, in her study on the iconography of tempers in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, noted that despite all the joy and exuberance depicted, in the end everything is meant to inculcate a moral and warn the audience against excess.4

I find these moralizing readings unconvincing. They are so for historical reasons, as has been brought forward in Tummer’s catalogue (itself a response to the powerful echoes of Simon Schama’s The Embarrassment of Riches from 1987).5 If the pubs and brothels truly were only morally objectionable, they would not have been represented in such numbers and with such apparent joy. Moreover, people were far from embarrassed to celebrate life, as existence of a festive culture is testified to in what we know of the private houses, gardens, and public spaces of the time. All this existed as abundantly as the laughing faces in the work of Hals. Contemporary views on the seventeenth-century Republic may still be suffering, here, from a moralizing approach that has more to do with the nineteenth century than it does an adequate understanding of the seventeenth. In his studies on laughter and humor in Dutch society, Rudolf Dekker has convincingly shown how in the seventeenth century a battle was being waged between those who loved jokes and joking and those who could not stop moralizing—and how this battle was won by the latter for coming centuries at the end of the seventeenth century.6

Secondly there are formal reasons, in this case, why a specifically moralizing reading of the painting is not convincing. They concern the painting’s focus of attention, which is not the glass that the man is carrying. The composition has been studied mostly in terms of how it directs the viewer’s attention to “a young man raising his glass.”7 That man is clearly looking upward diagonally—a direction that is emphasized by visual rhyming patterns. There are straight lines pointing in the same direction: one running from the dog’s face to one of the man’s arms, via the diagonal fold in his jacket, to the other arm; one from the wrist collar on the left arm of the woman; one from the face of the man at the back; and one from the ribs in the ceiling; finally there is the curved line of the feather, with the left part turning upward in the same direction. Especially the ribs in the ceiling formally emphasize that the man upfront, as well as the man in the background, is looking at something beyond the glass. The man is raising the glass, then, to something that lies outside the frame of the painting and the scope of the viewer. He is looking at something we have to guess at, because it is in the realm of the unexpressed (or perhaps even because it belongs to the realm of the inexpressible). The expressive face of the woman looking directly toward us does not fill this in, but, in contrast, appears to ask us what it is that the man addresses.

When Karel van Mander in his Schilderboeck indicated that it is incredibly difficult to catch the difference between laughter and sobbing in paint, he might have mentioned that the true master of laughter was (his pupil) Frans Hals.8 Indeed, the latter’s exceptional skill allowed him to represent happy people in a happy world in such a way that they affect us (as pointed out by Rudolf Dekker or, earlier, Seymour Slive).9 Still, this painterly skill cannot explain the painting’s affective power, which relates to the question of what the man and woman are laughing about, or perhaps better, what the intensity of their laughter hints at. Their hearty laughter appears to be an expression of defiance that, in my reading, turns this into a painting depicting some sort of sublime moment. The nature of this sublime moment is related intrinsically, then, to laughter, indeed to nigh unrestrained happiness.

The relation between the sublime and the comic requires further exploration theoretically. In Longinus’s treatise on the sublime the subject of laughter is mentioned at times but never fully developed. And in the European trajectory of the notion, laughter and the sublime seem awkward partners. In the work of Hals the two appear to be brought together, provoking the question of how the sublime is related, formally and in terms of content, to happiness and the comic. Such a question would not concern only the work of Hals. In the Baroque world of the Dutch Republic the comic played a role in all sorts of genres. More importantly, however, in the context of the sublime, I would argue that the medieval or Renaissance religious meaning of comedy found a worldly equivalent in the context of a Dutch Baroque.

The medieval or Renaissance form of religious comedy finds a paradigm in Dante’s Divine Comedy. Although the Comedy, especially in the first part, may have caused audiences to laugh, this laughter would have been in response to aspects that I would define in terms of the ridiculous. The reaction to the latter parts, however, would have been delight, the inexpressible joy of the sublime. Dante’s comedy sketches, counter to tragedy, a trajectory from bad to good, from hell to paradise. This form of comedy is not analogous to the abundantly produced comical, celebratory, literary, theatrical, and pictorial expressions of laughter in the Republic, and for two reasons.10 These comical pieces are hardly ever religious, and they are not “comedic” in sketching a trajectory from bad to good.

Still, Dante’s comedy may help us to find a way of considering the sublime in relation to the happiness captured in Hals’s work. With Dante, comedy consisted in the ultimately happy inclusion of one world into another, the earthly one in a divine one. In the medieval and Renaissance worldview the two worlds were not principally separate. Following the logic of neo-Platonism, the earthly world was a lesser emanation from the heavenly one and could therefore be included within it. The contention of this essay is that this possibility of inclusion was countered, in the seventeenth century, by the idea that there are several possible and real worlds that can, momentarily, coincide but that are principally separate. This was worked out philosophically first by Spinoza, and later by Leibniz, but the concept is also found in some works of art, as Thijs Weststijn has argued.11 The Dutch Baroque sensibility consisted in the realization that reality is multiple and momentous under the aspect of “creation.” This world, that is to say, is neither finished, nor predestined, nor framed. It is one out of many possibilities, and as such it is creative in nature.

In terms of “creation,” the sublime operative in Hals’s work can be considered as a form of comedy that is comparable to Dante’s while yet being radically different from it. Hals’s comedic sublime is worldly in that it relates to the actualization of a happy world as opposed to other, more wretched ones. All such worlds are equally real and intrinsically linked at some moment, after which they split apart to become disparate, separate realities. The sublime effect consists in the apprehension of these other, separate worlds. From now onward, I will call this “comedy-like” sublime comedic in order to distinguish it from the comic and the comical. The overwhelming power of the sublime, in this case, has a source in the human subject, in its relation to a lucky world that is only one among other possibilities. In this light, the young man in Hals’s painting is shouting “Ha!” to a different, more infelicitous world that could have been, but is not, his reality.

To avoid any misunderstanding, in what follows I will use the term sublime partly in accordance with how it is used in early modern Dutch writing, especially in the work of Daniel Heinsius, and much less so in that of Gerardus Vossius, for whom the sublime was predominantly defined by the element of its being overwhelming. Yet would this element be found only in art or could it also be an element of everyday reality? Or could it be an element of art in its relation to everyday reality? In what follows, I ask these questions in the context of what is a distinctly Dutch Baroque. Yet before going into the nature of this Dutch Baroque, for which I consider the work of Hals to be paradigmatic, let me first focus on a work of Jan Steen to make a sharper distinction between the comical and the comedic; and let me bring in a letter by Joost van den Vondel to make a sharp distinction between the possibly comedic or the tragic nature of history. Hals’s relation to these two figures will prepare the ground for showing in more detail why his work is an example of the comedic sublime, and as such paradigmatic for the Dutch Baroque.

From Steen to Vondel: Comical and Tragic Counterpoints to the Comedic

Philip Sidney was one of the earliest Baroque theoreticians in northwestern Europe. In his Defense of Poesy, published in 1579, he distinguishes between delight and simple laughter, which he defines in relation to the ridiculous, and then makes a further distinction between the ridiculous and laughter about “sinful things”: “Delight hath a joy in it, either permanent or present. Laughter hath only a scornful tickling.” And a little later:

But I speak to this purpose, that all the end of the comical part be not upon such scornful matters as stirreth laughter only, but, mixed with it, that delightful teaching which is the end of Poesy. And the great fault even in that point of laughter, and forbidden plainly by Aristotle, is that they stir laughter in sinful things, which are rather to be execrable than ridiculous; or in miserable, which are rather to be pitied than scorned . . . (151)12

Sidney’s treatise and these distinctions are useful in reading many of Jan Steen’s paintings, which in general, intend to teach something joyfully. Yet there are also Steen paintings that tend toward scorn of the ridiculous, or seem on the verge of laughing at what is sinful. In fact, Steen seldom missed an opportunity to use the ridiculous, pace the requirement brought forward by Aristotle; or to use the execrable, as when the audience is made to laugh about others and their silly or sinful behavior.

A good case in point is Gamblers Quarreling, now in the Detroit Institute of Arts, where, thanks to modern technology, the modern reader can find the ridiculous and the sinful in close (digital) detail on the museum’s website (fig. 2).13 Here, there is nothing of a palpable tension between two intrinsically connected but separate worlds. This is the world of the pub, with its games, drinks, prostitutes, and jolly meetings, and the audience is invited to laugh at the ridiculousness of it all, just as the three men at the back are doing. The ridiculous here has its etymological origin in iocus, game or pastime, and by extension joking or jest. For Sidney the ridiculous is related to scorn in that one is not laughing with someone but about them. Laughter could even devolve into the wrong kind of laughter, as when people laugh about matters that are not at all laughable, as here when someone draws a sword in order to kill in rage (as the figure on the right is doing) or when nuns are joining in with drunkards (as appears to be the case in the center). In such cases, Sidney suggested, laughter should fall silent, as we consider what is poor and hateful in terms of the execrable.

Yet I doubt very much whether Steen would agree here with Sidney. In the case of this painting clearly the three in the back will keep on laughing. To them the nun trying to control her drunken mate is not an issue of sin, and in fact their jeering seems to encourage one man to kill the other. All are part of the game. In this context Steen is distinctly not in line with a Baroque use of the sublime in the sense of the comedic. He is joking, as Rudolf Dekker has argued, or he is comical, as Mariët Westermann has shown in her study of Jan Steen’s work in the context of seventeenth-century comic painting.14 He might even be farcical and provoking laughter where others would fall silent. He belongs to the everyday world that he is so intimately depicting because he takes part in it.15 This is not to say that Frans Hals, in contrast, did not partake in the world of the pub. Yet, even when he uses scenes from it, they are not comical but rather comedic.

The latter term is exemplified in a painting by Hals entitled Laughing Fisher Boy (fig. 3).16 Here, too, we see someone laughing. Yet the painting does not make us laugh. So, again, what does it do? It is moving, literally and figuratively, and as a result clearly moves us. This effect, as Thijs Weststeijn suggested, was central to seventeenth-century Dutch art practice and art theories.17 It is as if the movement of the boy to the left is countered by the clouds amassing to the right. The boy is standing with his back toward this overwhelming force of nature. Any fisher boy would be able to tell that the weather can change rapidly. A small dark area behind the big white cloud at the right may even suggest that a thunderstorm is building up. As it is, however, the world is happy, and the enormous power of the clouds does not impress the human subject standing in front of it, but instead enforces his powers and ability to be in this world. In effect, the comedic embodied in this painting affects the audience in that, instead of reducing the spectator’s power, or humbling his or her status, it enhances those powers, heightening her or his body’s capacity to act, as Spinoza would say. Captured in the specificity of this world, the comedic acknowledges that life could have been so different.

The comedic is an obvious counterpart, here, to the tragic, a mode of dealing with things that was crucial to another Baroque icon in the Dutch Republic: Joost van den Vondel. In a letter to Hugo Grotius dated September 9, 1639, Vondel confessed that, after one and a half decades of attempts and despite promises, he had stopped working on a major epic work. This is what he wrote:

I am offering Your Excellency what lies in my power, not what I would want. Since the death of my beloved wife my energies have gotten a blow so that I will have to forget my great Constantine and to make do with something smaller. . . . If I have grown tired of writing tragedies, I will see whether I will get back to my Constantine; meanwhile I ask Your Excellency to accept this for what it is, until we find the strength for bigger things.18

To say that Grotius was Vondel’s close friend would perhaps be an exaggeration, but the two had always remained in close contact, ever since Grotius became one of the political casualties in the process instigated by Stadholder Maurits against Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, which led to the latter’s traumatic execution on May 13, 1619. After his imprisonment in the castle of Loevestein and his spectacular escape, Grotius had fled the country, and after 1632 was officially banned for the rest of his life.

Vondel’s alliance with Grotius is interesting in relation to the simultaneous existence of worlds, for two reasons. The first one is that the situation in the Republic was so politically charged because it embodied the split between a monarchical and a republican option for organizing the world. Taking sides with Grotius implied that Vondel was opting for the republican world and was thus bound to have a complicated relationship with the members of the House of Orange. He certainly never forgave Maurits for having killed Oldenbarnevelt, and his relationship with Frederik Hendrik was ambivalent. Then, after having glorified the birth of William II, Vondel called him a Lucifer when William tried to occupy Amsterdam in 1650 and welcomed his untimely death. Had Vondel not stopped writing because of old age he probably would have taken up his pen in rage in 1672, the year that announced the monarchical rise of William III after the lynching of two republican icons: the brothers de Witt. The second reason is more pertinent and concerns the very nature of the making of history. Grotius had suggested that Vondel write an epic on the Roman emperor Constantine, whom the republicans saw as a model for a unified religio-political European order. Grotius was looking for an artistic underpinning, here, of his efforts to restore the one and only Church and end the religious strife and sectarianism that was ripping Europe apart. Vondel supported this endeavor. He had begun his work on Constantine in 1623; by 1634 he had completed five songs but then stopped writing, and destroyed the manuscript, sixteen years after starting.

Joachim Oudaen, a long-standing opponent of Vondel’s who admired him as a poet, suggested to Vondel’s biographer, Gerard Brandt, that the reason was that Vondel had come to realize what an odd Christian hero Constantine was. He had murdered his son Crispus (who was in his early twenties) and his second wife Fausta (by having her suffocated in a much-too-hot bath), because they were rumored to have had a sexual relationship.19 Interestingly enough, a sexual relationship between stepmother and son, which sources suggest Fausta attempted to set up, would have fascinated Vondel. This story would have resonated explicitly with the stories of Hippolytus and Joseph, in which powerful women (one of them a stepmother) declared their love to a resistant or fearful but in any case innocent young man. Vondel wrote no less than four plays on the theme (in 1628, 1635, and two in the year that followed the letter to Grotius, 1640). The tragedies revolved around at least three basic forces: that people are driven by uncontrollable passions, that history consists of sequences of contingent events and mistakes, and that consequently happy outcomes are possible but not likely. In this light Constantine’s killing of his (innocent) son was a gross mistake, and an unforgiveable one. As a consequence, he embodied less the unity and coherence of history and more its contingency, or even fragmentation, thus highlighting that absent his passion the world would have been different.

Connected to the issue of history’s unity, there was a generic problem in play as well. Theoretically speaking epic was still considered the most eminent serious genre at the time (the authority here was Vossius, as always).20 Yet Vondel struggled with it. In my reading this was because of the epic’s narrative ordering, its necessary logico-chronological sequence of events, and the required narrative closure—in short because of its classicist linearity. Being too much of a classicist as well, Vondel could not have written a Baroque narrative, such as Grimmelshausen’s The Adventurous Simplicimmus. The only truly epic piece he wrote, Johannes boetgezant (John the Baptist) from 1662, at age seventy-five, came closer to his vast Bespiegelingen van Godt en Godtsdienst (Reflections on God and Religion) from the very same year. This is to say: these were less epics than treatises. Vondel was a playwright, artistically, in terms of capabilities and inclinations, but more importantly and more in line with Baroque thinking, he was also a playwright conceptually in his view of history’s dramatic openness or, better, history’s interrupt-ability, which was in turn related to the intensity of a moment.

The Sublime Intensity of the Moment

As discussed above, Young Man and Woman in an Inn has earlier been considered to be a depiction of the prodigal son in his exuberant and sinful life before his downfall and the return home. Such a reading of the painting fits in with the logic of our living in a single predestined and prefigured world. That Hals is following another kind of logic is evidenced by Young Man Holding a Skull, from around 1626 (fig. 4). When Seymour Slive contended that the young man depicted could not be Hamlet, as argued by Hofstede de Groot, since there were no English theater companies traveling through the Netherlands either prior to or in the 1620s, he was simply wrong.21 Moreover, when he contended that the painting fits seamlessly with other vanitas paintings he was wrong again. In most such paintings, the man (it is mostly a man) holding the skull is looking the viewer in the eye. Not so in this case: the healthy young man extends his hand toward the viewer, from beneath a cloak that is layered in many folds. He holds the skull lightly, looking not at the viewer but in the very direction at which the skull with its empty sockets is pointed. The feather drooping downward from his hat forms a square that leads the viewer’s eye in a clockwise direction, with the outstretched hand coming between the skull and the young man’s face and creating a tremor between two possibilities: life or death—“to be or not to be.” His eyes show that they know what is at stake, at this very moment. There is no exuberance here, and no drinking. The young man’s face is one of the most complex Hals ever painted, and his eyes convey his wary attitude, which is neither exuberant about life nor defiant as opposed to death. This is certainly not a gloomy, melancholy, or otherwise troubled young man. It is a young man being aware of the openness of a dramatic moment.

To Vondel, formally or aesthetically speaking, narrative resembled too much the organization of history through predestination, which was a major and even dominant target of criticism in his work. In contrast, drama—not so much theater but drama—offered the possibility of enacting, reenacting, and thereby regenerating choice in relation to the charged moment. Drama was the best generic form for presenting choices, in their dramatic reality and potential, between two equally real worlds. The dramatic consisted in the fact that choices inevitably lead to one out of a set of possible worlds. And, tragically, people tended to make the wrong choices more often than not. The element of choice was pivotal, then, to Vondel. With regard to this, even when his tragedies complied with Aristotelian requirements, they remained, in one way, distinctly non-Aristotelian. They reduced the importance of plot while increasing the importance of interruption.22 In another way he was distinctly Aristotelian with respect to the distinctive moments in the play. The peripeteia, the moment of reversal, or the anagnorisis (or agnitio), the moment of sudden insight, could function as breaks in the plot structure that opened it up. Paradoxically this may also explain why Vondel’s plays favor (at times lengthy) argumentation above action. Actions, driven by plot, enforce choices or result from choices. Argumentations, in contrast, test choices or make them possible. Vondel’s characters are not caught in plots, they are enwrapped in arguments, wrestling with them in a distinctly Baroque way especially because of the narratives into which these arguments are folded. In contrast to Walter Benjamin’s analysis of the German Traurspiel, Vondel’s world is not a world of fragments but of Deleuzian folds.23

It is not an exaggeration to state that what happened in the Republic fascinated many, exhilarated many, as the paintings by Hals show us. It also frightened many. One deep fear, perhaps even a basic one, is described in a study by Gerard Brom from 1935 entitled Vondel’s geloof (Vondel’s belief). For Vondel the correct historical order of things would be captured by the threefold sequence God—Jesus—Church. God created the world and mankind, then sent his son Jesus Christ to free mankind from its imprisonment through and after the Fall, as a result of which the one and only Church could come into existence. The shocking reversal of this order witnessed by Vondel, Brom argues, not just implied but actualized another history and world. This was a world in which Luther had blown apart the one and only Church and in which the Sozzini brothers denied the divinity of Jesus (Socinianism), the radical consequence of the latter being that God did not exist as the creator of this one world.24 This would indeed be the powerful conclusion proposed by Spinoza. Such a dramatic reversal implied much more than an unbalancing of the scales of history—the very inversion raised the possibility of different possible and co-existing worlds. At this point it is pivotal to see how the coincidence of real worlds is distinct from the collision of a real world with an imaginary one, and also different from defining a world theatrically. Even if we consider the figure in Young Man Holding a Skull to be an actor playing Hamlet, it is clear that, in a way analogous to the main figure in Young Man and Woman in an Inn, he is looking out of the scene. He is not piercing a theatrical fourth wall by addressing the viewer directly. Instead his eyes suggest that outside of the frame there lies “something else.”

On art’s potential to imitate not just one existing and real world but also to produce other imaginary ones, Philip Sidney had been explicit in his Defense of Poesy. In his conception, poetry (and by extension art) was not imitative but, by means of imagination, was able to produce new worlds if the artist was able to use the zodiac of wit:

Only the poet, disdaining to be tied to any such subjection, lifted up with the vigour of his own invention, doth grow in effect into another nature, in making things either better than Nature bringeth forth, or, quite anew, forms such as never were in Nature, as the Heroes, Demigods, Cyclops, Chimeras, Furies, and such like; so as he goeth hand in hand with Nature, not enclosed within the narrow warrant of her gifts, but freely ranging within the zodiac of his own wit. Nature never set forth the earth in so rich tapestry as divers poets have done; neither with pleasant rivers, fruitful trees, sweet-smelling flowers, nor whatsoever else may make the too-much-loved earth more lovely. Her world is brazen, the poets only deliver a golden.25

Art is able to produce worlds, then, that extend beyond the given world, and artists have their own zodiac apart from the celestial one. Read through the lens of this quote, Hals can be a good example of this, in his own Dutch and worldly way. He is not so much projecting new utopian visions or imaginary figures, however, but instead “imagines” real figures, from everyday life, that embody the world’s “richness.” Despite the ordinariness of his figures, that is, he has “the God-like power to transform audiences, a power that is, in everything but name, creative.”26

Still, the transforming power of Hals’s work suggests that there is something different in play, here, than a matter of imagination. Art works may project imaginary things beyond what we can see in nature, but as such, once in existence, art works still introduce these imaginary things into this one world. The Baroque dynamic that Hals is able to capture is not much concerned with the exuberant conjuring up of imaginary worlds. It is more concerned with so-called counterfactuals, related to the momentous splitting of worlds that could have been real for a split second and then separated irretrievably, but that linger on through a “what if.” It is this “what-if-ness” that is captured best by the young man’s face, in Young Man Holding a Skull. The comedic sublime works to capture the intense nature of the one world, here and now, that is actualized and in which one finds oneself.

Worldliness and Worlds in a Distinctly Dutch Baroque

Two paintings hint at the surely extraordinary, and in a sense even excessive, intensity of the moment in Hals’s Amsterdam. The two were made somewhere around the same time as Young Man Holding a Skull, around 1628, and they present the same figure although they bear two different titles, respectively: Man with Jug, also known as Peeckelhaering (fig. 5), and Mulat (fig. 6).

The titles do not indicate a meaningful difference between the two paintings; they were assigned to them in later years. Both paintings depict the same figure, as his costume, which has its source in English theater, shows.27 Since 1618 the term peeckelhaering in Dutch has indicated a clown, a character who is not so much himself laughable (or ridiculous) but who provokes laughter. In the first decades of the seventeenth century English theater companies touring the country had introduced this figure to the Dutch audience and since then several farces had been made with a Peeckelhaering in the leading role, and he had been depicted in several paintings.28 In relation to what I discussed earlier the character would fall under the rubric of the comical or the farcical. As for his tendency to express awkward truths, the Peeckelhaering could even fall under the rubric of the delightful. Yet the fact that there are two paintings of the same figure, painted from opposite viewpoints, suggests that we should consider the painting as representing more than just a theatrical character. The man, even in this costume, could also be someone who could have been encountered in the reality of everyday life, in one of Amsterdam’s pubs, in Amsterdam’s harbor, as a member of the many business companies visiting Amsterdam, or as someone taking part in one of the public or private theatrical festivities. In its depiction of such a figure, so Noël Schiller (2006) has argued, the painting would invite the viewers to become part of that reality.29

I suggest that through these two paintings we can trace a typically Dutch Baroque, and I say this fully aware of the fact that the very notion of the Baroque is “slippery,” all the more so when used in relation to Dutch art. Introductory works are telling, here, such as Baroque Art by Victoria Charles and Klaus Carl, who included a chapter on “Baroque in the Netherlands” but ignored the pivotal difference between the Republic and the Spanish Netherlands and considered both, moreover, as just one specimen of a more general (and sketchily defined) Baroque.30 In contrast, Babette Bohn and James M. Saslow state that Baroque is often shorthand for seventeenth century, but they consider it to be a complication that the Baroque’s “opulence and grandiosity are far less applicable to Dutch genre painting.”31 This only holds, of course, if one starts from the premise that the Baroque is southern European in origin and nature, and if one holds that the Baroque indicates a period. To be sure, the same authors are willing to admit that no age is ruled by one and the same mentality or style. As for the distinction between style and period, yet another quote is telling: “Indeed, the stylistic, as opposed to the chronological, designation ‘Baroque’ is ill suited to these seventeenth-century northern European artworks.”32 In this context, Christopher D. M. Atkins is more to the point when he states that Baroque is first of all more a stylistic than a temporal term. Yet he joins a familiar chorus in saying that the term Baroque “does not adequately describe Dutch aesthetics or the cultures of the Dutch Republic.”33 This begs the question, of course, how one can adequately describe such a specific form of Dutch aesthetics adequately as a style that still has distinct historical anchors in its period.

In the Dutch case, and in what one could call an opulent and grandiose “many cultures” society, the notion of the Baroque can be used to indicate not a period or a style but a materially actualized mode of worldliness and way of being in the world. In this light, and considered together, the two Peeckelhaering paintings address not so much the thin line between the theater and the real world, but instead capture the Baroque theatricality of Amsterdam’s and the Republic’s daily reality, which was the result of their dramatically actualizing a world. The Dutch Baroque is distinctly different here from the more familiar, southern European or Italian Baroque, as sketched by Zakiya Hanafi on the basis of a distinction between two lines of thinking:

If we characterize the conservative and moderate Baroque critics (Peregrini, Pallavicino, and in most respects, Baltasar Gracián) as viewing the rare and extraordinary as a means to revealing divine harmony, the radical critic tended to see the rare and extraordinary rather as monstrous in themselves, and conversely, monstrosity as the very essential nature of the universe.34

Almost nothing of this kind is the case in the Dutch Baroque. The universe is not so much considered in the light of wonder and the wondrous, or the rare and the extraordinary, let alone the monstrous. Both universe and daily reality are considered with fascination because both are marvelous.

In defining a distinctly Dutch Baroque aesthetic in the Republic, we would have to say farewell to the strong opposition brought in play by Nietzsche, in Human All too Human, that Baroque art is the opposite of classicist art. In the Dutch Republic they went hand in hand, with the Baroque winning out because of the very fact that Baroque dynamics work by means of opposites. A good case in point would be the Republic’s iconic author, whom we met earlier, Joost van den Vondel, whose work was at first received by some as Baroque in character, mostly in Catholic circles.35 Yet whereas in the second half of the twentieth century the major take on Vondel was that he was a classicist, the last two decades have witnessed a strong revival of the Baroque aspect, in which Vondel’s work is indeed considered as a mixture of both. Analogously, the reality on the societal floor in the Republic could well be described in contemporary aesthetic terms as a matter of misto: a mixture of styles resulting in a fascinating totality.36 My reconsiderations of the Dutch Republic as Baroque in nature were propelled, indeed, by the misto that defined sociocultural reality in the Dutch Republic and its hub, Amsterdam. All in all, the Republic succeeded in realizing not a secular as opposed to a religious Baroque, but a worldly one.

My use of the adjective “worldly” here is meant to circumvent the dichotomy of religious versus secular, with its connotations of belief versus rationality, tradition versus enlightenment, magic versus disenchantment. The term worldly may also serve, moreover, to escape defining the Baroque within the confines of either Catholic papal or royal absolutist terms. I consider the title of Mariët Westermann’s 1996 study on art in the Dutch Republic to be well chosen: A Worldly Art.37 The Baroque worldliness of the Dutch Republic was, in some aspects, deeply religious but also radically rational, as in the work of Franciscus van den Enden and Spinoza. It was in part quasi-royal but also distinctly civil. In all cases this worldliness displayed an intensity that had its own forces of enchantment. It also concerned the way in which the Republic and Amsterdam found their place not just in an already established world but in an actualized a world, a new world that was not so much distinct from the New World on the other side of the Atlantic but that was at the very basis of that new-ness.38

Beyond a doubt and also almost beyond comparison, the work of Frans Hals was witness to, and a material expression of, this joyous Dutch Baroque style. In the context of a Dutch republican and therefore “anomalous” Baroque, Hals’s work can be considered in terms of the sublime with respect to the reality of this world, a world that becomes not only more intensely experienced, although this is surely the case, but also becomes itself intensified. This alone would not be a reason to call it sublime. Such a form of the sublime would border on more familiar aesthetic strategies indicated by notions such as misto (or acutezza), when contrasting styles or notions are brought together. Emanuele Tesauro, for instance, argued that this could be effected by means of antithetically activated metaphors.39 Yet the collision in play here is by implication neither metaphorical nor allegorical. In my reading Hals’s comedic sublime taps into a collision between a real world and another, equally real, possible world that did not materialize, however, and as such can only be sensed indirectly.

Art Preparing the Grounds for Philosophy

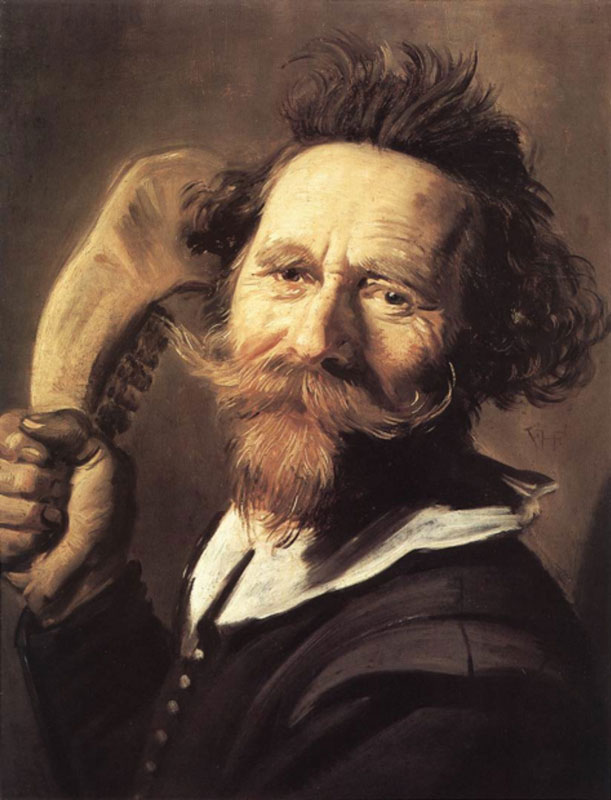

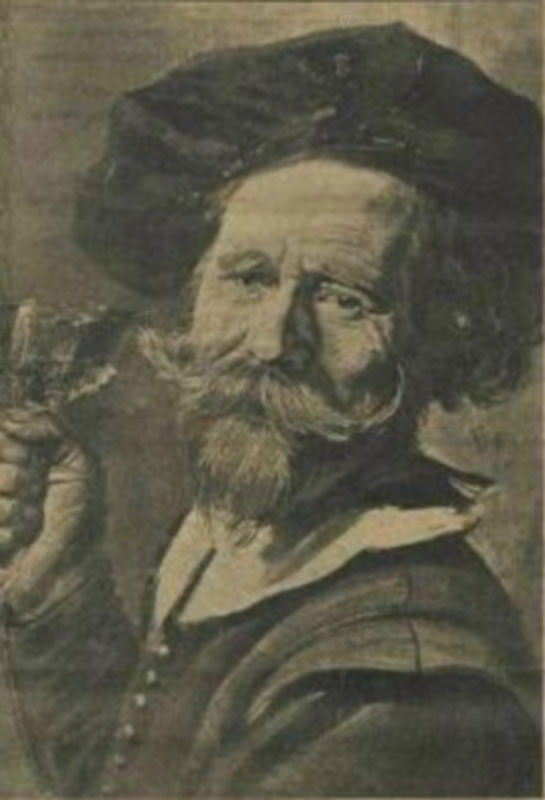

The Baroque concept of the possibility of radical divergences in worlds and in real history should be sharply distinguished from the poet’s or artist’s capacity to imagine other worlds. In that context it is of more importance to consider that the actualization of one world as opposed to others could be welcomed, if it so happened that it brought one to a prosperous, happy world. In terms of the Dutch Baroque this one world is, consequently, not so much experienced as the one and only real (or, for that matter, transient) world, but as the dramatically realized, almost dreamlike world that exists in relation to other worlds but from “now” onward in sublime solitude. Hals’s work testifies to this, for instance, in Portrait of a Man with a Cow’s Jawbone in His Hand, also known as Verdonck (fig. 7 and fig. 8).

The painting becomes “alive” because of the way the jawbone seems to be moving, as if in swing, whereas the hair on top of the man’s head makes it appear that his head is moving forward in aggression. At the same time the relatively benign smile of the man suggests the opposite. As a result there is a contrast in play within the painting that brings us to the moment at which two intrinsically related possibilities are simultaneously real. Such a reading is a radicalization of the concept of acutezza, which comes in play with an etching that was made of the painting by Jan van de Velde II, along with a poem of explanation:

Dit is Verdonck, die stoute gast,

Wiens kaeckebeen elck een aen tast,

Op niemant, groot, noch kleijn, hij past,

Dies raeckte hij in ’t werckhuis vast.This is Verdonck, that bold bloke

Whose jawbone will give everyone a stroke

He cares not be ye big or small

The house of correction was his call

The etching, the painting, and the historical man depicted, who gave the painting its alternative title, have been convincingly contextualized by P. J. J. van Thiel, who explained that the historical Verdonck did not really violently attack others but used his “jaw” (mouth) as a powerful weapon in a fierce conflict, in this case between two Haarlem-based parties of Anabaptists.40 Van Thiel also noted that the painting obviously alludes to the biblical story of Samson, who killed a thousand Philistines with an ass’s jawbone.

At first glance there appears to be a witty intertextual, anachronistic Renaissance-like dynamic in play here. Yet the fact that this is not an ass’s jawbone, but a cow’s suggests a difference that may be pivotal. Or, it makes a difference, opening up different worlds by representing two counterfactuals related to two separate historical worlds. There is a comical one: what if Samson had had a cow’s jawbone instead of an ass’s? There is a more serious one: what if Verdonck had really attacked people with this jawbone? The momentous reality of this dual option is confirmed, in this case, by the fact that fairly soon after the painting was made, a wine glass was painted over the jawbone, and the man’s wild and expressive hair was covered by an elegant beret. The result is telling in the context of my argument. The first version is “Baroque,” the second is not. The second one has lost the dynamic tension between the sublime moment at which two radically different worlds meet.

Hals’s work can be seen, here, as preparing the grounds, artistically, for what would later become a pivotal philosophical issue. The problem of how to think of this world in relation to equally possible others was key, half a century later, to the paradigmatic Baroque philosopher Leibniz, who introduced his ideas of separate enclosed worlds, so-called monads, with La Monadologie, in 1714. For Leibniz and many of his contemporaries, including Spinoza, a major philosophical riddle to be solved was the issue of causation in a God-made world that consisted of different substances. In addressing this issue, Leibniz referred back to the theory of occasionalism, which concerned the way in which things are caused and how this could involve entities that were created differently, consisting of, indeed, different substances. Was it the case that God was a “prime mover,” who had created different substances, by means of which he set things in motion and after which they continued to change? If so, did things change due to secondary efficient causes or simply as a result of the first divine causation? And how could things that were made of different substances, such as matter and mind, have causal relations with one another? In answer to this question, the most radical version of occasionalism held that all cause-effect relationships were just illusions—God recreated the universe in each instance anew.

The modern mind, to the evolution of which the Baroque forms a pivot, rejects all forms of occasionalism, radical or not, as happened with Spinoza and Leibniz, though with a twist. As for Leibniz, he agreed that there are worlds that cannot affect one another causally if they are created from different substances. It is only within one world that effective causes may be seen to work. This led him to state that there are different, radically separate worlds, which he called monads, that are not able to relate to one another in terms of cause and effect. According to Leibniz the monadic world we live in was the one chosen by God because it was the best one, that is to say: the most intense one. For Spinoza, the possibility of other real worlds was, in one sense, of little value. Radically materialist as Spinoza was, he rejected the actual co-existence of possible and real worlds. Yet this was not because he thought that our world is the only possible, let alone predestined, one. His question was how this world was necessitated, on the basis of the principle of sufficient reason, a theme he worked out in Ethics. There he stated, for instance, “if a certain number of individuals exists, there must be a cause why those individuals, and why neither more nor fewer, exist” (Ethics, part 1, proposition 8, scholium 2). So, if this world can be considered one out of a myriad of possibilities, the question does indeed become what necessitated it, and why it did not become another, different, world. The question even becomes how the non-existence of a world can be explained.

At stake, in the end, was the very nature of history, and whether it was man-made, mechanically made, or divinely predestined, or, more crucially, whether history was free in the sense that it could develop in any kind of direction. Instead of steadily moving toward a predestined goal, history could be ruled by ruptures, could be whirling instead of progressing in a linear line, could even be considered as fragmented, as Walter Benjamin or Eugenio d’Ors would have it. It is this turbulence of worlds in history that is distinctly Baroque, and that should be defined in terms of the sublime. When Greg Lambert discusses the current “return of the Baroque,” he notes that such a return is “inscribed within a negation of historical causality,” by which he does not deny causality per se but the so-called necessity of historical continuity.41 With respect to this issue, I consider the Dutch Baroque to be sublime in the sense that it brings us either to the split-second and overwhelming moment of simultaneous realities or to the consequent unbridgeable gap between them. The world’s infinity, in this respect, consists in its being made, practically,42 or its being actualized out of co-existing, possibly real or really possible other worlds, as a result of which the one actualized world does not have one final cause.

With regard to history, the tragic sublime overwhelms by confronting an audience with the world’s solitude in the unfortunate outcome of unpredictable, seemingly fated actions, In contrast, the comedic sublime overwhelms because of what the human subject is capable of in actualizing a separate world, in which death is not paramount but in which prosperity and happiness, or luck, dominate. This cannot be a matter of simply making such a world. Anybody who was twenty in 1590 and fortunate enough to attain the age of sixty, would forty years later, in 1630, have lived in a radically different Amsterdam than the one of their birth. Someone who was twenty in 1615 and lived to see the new City Hall in 1655 would have lived in yet another Amsterdam. Many things had been made in republican Amsterdam, and by it. Yet the way in which Amsterdam had found itself, as the economic hub of the Republic in Europe and a new global economy, was dramatically actualized, moment after moment, in a world that was constantly split off from the previously known one, or from another, unfortunate. one. Frans Hals, more than anybody else, managed to capture this dynamic from the happy side. In his work he manages to capture the comedic sublime.

Almost as a consequence, Hals’s work is testimony to the end of a metaphor that had pervaded a common worldview under different aesthetic regimes for centuries. This is the theatrum mundi, which, in the Christian view, presented the fickle stage of the world under the stable view of God. Hals’s contemporary, Vondel, explicitly fought against the very reversal that was taking place or had already had taken place in the Dutch Republic, and although Vondel would have loved to see the world in terms of classicist theatricality, much of his work testifies to an impulse that would fit into what I have called elsewhere a Baroque mundus dramaticus. Vondel’s work did not so much embody this new, dramatic, Spinozean world, but instead was overwhelmed by it, wrestled with it, and, as with real wrestling, hovered between laughter and groan, between force and exhaustion, between despair and joy, between coherence and incoherence, between irenic desire and violent conviction, linearity and fold. Hals, in contrast, simply embraced this new, Baroque world, finding infinity in the fold. If his work overwhelms it is not because of a divine presence that towers over this world but because he captures with expressive, painterly means an inexpressible, worldly joy.