On August 20, 1672, the brothers Cornelis and Johannes de Witt were brutally murdered in The Hague. They fell victim to a political and populist hate campaign engendered by their deliberately anti-Orangeist stance and by the extremely difficult political and military situation of the Republic of the Seven Netherlands in that year. Around the body parts of the dismembered brothers a memory cult arose among both their political opponents and their adherents. This essay concentrates on the processes of appropriation and rejection, in prints and medals, of the iconic painted portraits of the brothers produced by Jan de Baen and Caspar Netscher immediately after their deaths. In particular Jan de Baen’s allegorical portrait of Cornelis de Witt — created for the Dordrecht town hall after the victorious Dutch raid on the Medway of 1667 — appears to have sparked emotions in 1672 and later. After some months of vehement exchange, artistic production accommodated to a policy of deliberate and officially promoted forgetfulness in which the life and death of the brothers De Witt were inscribed into a much broader policy of reflection with humanistic overtones.

“Stand still, forget about [these] painting[s]!” (Sta stil, denk aan geen schilderyen)

— Joachim Oudaen, Haagsche broeder-moord, of Dolle blydschap: Treurspel, 1673 (1712), Act IV, v. 2347

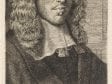

On a day in the late spring or early summer of 1672, a furious mob entered the town hall in the city of Dordrecht. Their wrath was aimed at a painting that the Dordrecht city council had ordered from a prestigious portrait painter in The Hague, Jan de Baen, after the victorious raid on the Medway by the Dutch fleet in the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–67) in June 1667. We know what this painting looked like thanks to a contemporary, slightly different copy (or maybe a model), now in the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum (fig. 1).1 The occasion so festively glorified in this painting is the bombardment of the town of Sheerness by the fleet of the Seven Provinces under the admiralty of Michiel de Ruyter and the supervision of Cornelis de Witt as the official representative of the States-General. The fleet sailed up the river Thames to Gravesend, and from there to Chatham on the Medway, where it sank thirteen English ships and captured two others, among them the English flagship the Royal Charles, which the Dutch towed triumphantly to Holland. The ship’s coat of arms can be seen to this very day in the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum.2 The raid on the Medway was of decisive importance to the development of this war and set England back for years in its efforts to restrain the Dutch position on the international seas.

In those summer days of 1667 the brothers Jan and Cornelis de Witt were at the apogee of their power and prestige. Jan was raadpensionaris (secretary general) to the States of Holland, the most influential position in Dutch seventeenth-century politics. And Cornelis was a bailiff of the isle of Putten, a member of the city council of Dordrecht, the oldest city in Holland, having served as its burgomaster in 1666 and 1667 and since 1665 as the official representative in instances of war on behalf of the States-General, the national assembly of provincial representatives which decided questions of international warfare.3

Five years later Cornelis de Witt appeared to have lost all of his prestige in the eyes of a majority of the population of his hometown. On his return from the sea battle at Solebay off the Suffolk coast, on June 24, 1672, the opening battle of the Third Anglo-Dutch war (1672–74), which proved to be disastrous to the Dutch, he must have realized that he was setting foot on the shores of a Republic in which the popular mood had changed completely. The Republic was under threat by the armies of the king of France, as well as those of the bishops of Minster and Cologne (part of which was massed at the border and part already within the territory of the Dutch Republic), and by the English fleet. While Cornelis had resigned his duties as representative of the States-General to the Dutch fleet as a consequence of serious illness, rumor had it that he had given up on the Dutch case altogether, and on the streets of the Republic his younger brother Jan was being accused of betraying the Dutch cause to the French.

The crowd that broke into Dordrecht city hall knew very well what they were after. It must have taken Jan de Baen three years to finish his allegory on the triumph of Cornelis de Witt at Chatham. In July 1670, the painting, beautifully framed, had been hung in the town hall, with a dedicatory text by the city council written underneath on the carved wooden frame.4 Its existence had not gone unnoticed. Romeyn de Hooghe had produced a well-known engraving after the original,5 which must have reached the English court, since Charles II raised serious complaints against its iconography, which showed little respect for the English.6 By the summer of 1672, some people in Dordrecht must have thought that the predicament now facing the Republic in that annus horribilis could, at least partly, be blamed on the pride and arrogance of their regents in general, and on Cornelis de Witt in particular. After entering the town hall, the mob ripped the painting off the wall and took it outside, where the canvas was torn to pieces (fig. 2).7 The painted head of Cornelis de Witt was cut from the canvas, taken triumphantly to the other side of the river Merwede, and subsequently nailed to the city gallows standing there.

We know this type of ritual killing of political opponents from all kinds of early modern satirical prints and pamphlets, where it is usually formatted as a burial of someone deeply hated.8 This time, with the attachment of the truthfully painted portrait of Cornelis de Witt to the city gallows, the mob came frighteningly close to the act of really killing the person in question. While character assassinations of Cornelis and Johan de Witt had been committed repeatedly over the past few weeks, physical murder now seemed to be impending.

In hindsight, we all know, of course, where this was leading: the killing of the brothers De Witt on August 20, 1672, in The Hague. And although the events in the summer of 1672 were evidently far from normal or regular in the history and art history of the Republic, it is worth taking a closer look at some portraits of the De Witts, especially in prints and on medals, to learn more about the political and social importance of portraiture in Dutch seventeenth-century society.

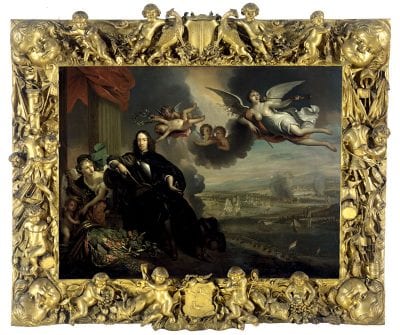

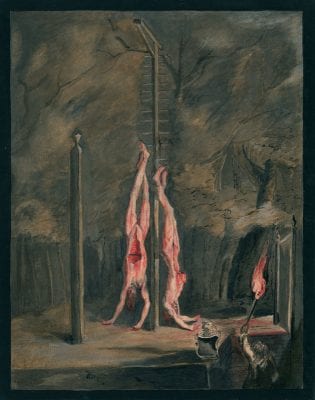

The impact of the slaying of the brothers was obviously tremendous, but portraiture did not play a prominent role in artistic output immediately after the event.9 One could argue that some of the horrific images of the mutilated bodies of the brothers, hung upside down (another ritual act with great symbolic impact) from the gallows in The Hague, could be interpreted as some kind of inverse political double portrait. They were probably not so much considered as portraits but rather as abhorrent examples of what could become of those in power. In a way, we are talking about the counterfeits of two dehumanized figures, two human beings who had been reduced to the status of slaughtered cattle, carcasses really, whose ears, noses, lips, fingers, and even genitals had been cut off and sold.10

The most famous and often reproduced image of this kind is a small canvas in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, traditionally attributed to Jan de Baen, the same painter who had produced Cornelis de Witt’s triumphant portrait-allegory in 1667–70 (fig. 3). The attribution — which goes back to 1802 when the painting entered the national collection of the Batavian Republic as one of its earliest acquisitions — is doubtful. But a contemporary or slightly later inscription on the back of the painting claims that it was by “an outstanding painter after life” and that it was the only existing “principal [original painting of the event] after life . . . and on that account worth much money.”11 Indeed, painted representations of events like these in the history of Dutch painting are very scarce, first of all, fortunately, because of the relative tranquillity of Dutch political history but also because the crude realism that a picture like this implied was not deemed worthy for history painting. Drawings (fig. 4), and especially prints were therefore much more suited for this type of representation and social interaction.

The Historical Museum in The Hague still holds some parts — a tongue, the bone of a finger (not of a toe, as was thought until recently) — of the bodies of Johan and Cornelis. These are neatly kept in a miniature glass coffin, and in the years after the brothers’ murder were venerated as secular, political relics. We know that a modest cult of remembrance of the brothers flourished in the decades after 1672, especially in Remonstrant circles, where the brothers were incorporated into a pantheon of the so-called Loevestein or staatsgezinde (that is, without a stadholder), anti-Orangeist regents and martyrs for the “True Liberty” of the Republic.12

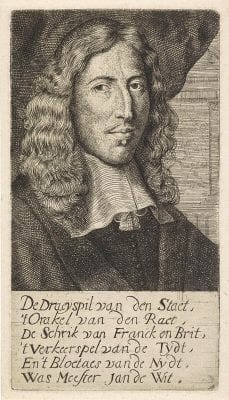

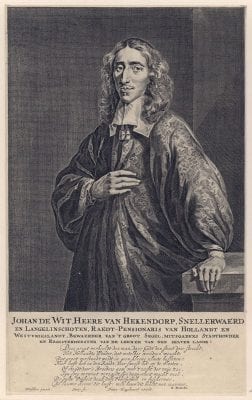

While the earliest artistic expressions of the events of August 20, 1672, concentrate on the sensational news of the death of the brothers and the way this took place, traces of an outspoken political perspective, whether in a positive or negative sense, can be found in some of the early posthumous portraits of the brothers. In a portrait print (fig. 5) that was probably inspired by the original painted state portrait by Jan de Baen depicting Johan de Witt in the assembly hall of the States of Holland,13 the accompanying poem speaks of him as the axis of the State, the oracle of the Council, the terror of French and Britons alike. These were clearly positive qualifications without reserve, just as the description of De Witt as “the bait of jealousy” defends him even in his final hour.

A process of appropriation and rejection was sparked off immediately after August 1672 around another earlier portrait of Johan de Witt, originally painted by Caspar Netscher but widely known through an engraving by Hendrik Bary, with a laudatory poem by the Remonstrant Geraert Brandt I (fig. 6). At the apogee of De Witt’s fame, Brandt had called for a marble bust to be modeled after Netscher’s image to eternalize the numerous merits of the raadpensionaris. But now one anonymous author, obviously writing in the heated days of July or August 1672 and providing a dextrous variation on Brandt’s poetic scheme, made a public appeal to erect a statue to the man who dared to crush De Witt’s head. Yet another encouraged his fellows to cut out De Witt’s heart and kick his head to pieces.14 Fierce reactions like these are also found in dozens of pamphlets that were issued in the early days after the murders. In these, basic oppositional schemes are followed — good versus evil, white (“wit,” “witt”) versus black, night versus day, heaven versus hell (the devil in this scheme being white), triumph and defeat, the brothers De Witt usually taking the part of the bad guys who eventually got what they deserved.15

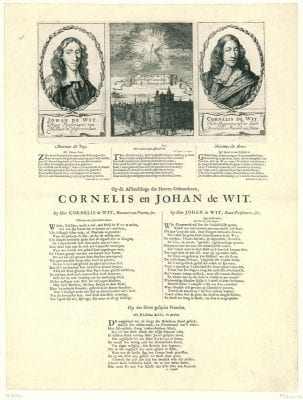

Given the hotly disputed position the De Witt brothers appeared to be taking within the political structure of the Republic, and remembering the violent incident in Dordrecht targeting De Baen’s allegorical portrait of Cornelis de Witt, it is no wonder that we hear echoes now and then of that event in later comments. In one of the very few pamphlets that had the courage to defend the brothers in 1672, we observe their two portraits flanking an emblematic image of twin stars that, as in Valerius Flaccus’s Argonauts, quoted underneath this image, had risen high but must inevitably fall (fig. 7). Interestingly, the anonymous author of the text that accompanies these portraits reminds us of the Dordrecht incident in a poem on Cornelis’s image, where he warns the artist not to paint hero Cornelis against a backdrop of his torture and fatal ending in The Hague, nor even against his victory at Chatham: jealousy would prevent such depictions, or would destroy the work. Rather, the artist should paint Cornelis in his costume of representative of the States-General, as in his portrait by De Baen, in which case the spectator would remember that it was “that furious mob” that brought Cornelis down, and not the States-General.16

In Joachim Oudaen’s tragedy Haagsche broeder-moord, of Dolle blydschap, dating from 1673 but not published any earlier than 1712, we find the same train of thought. In the fourth act of this play, at the very moment when people from the lower classes start threatening the brothers and pulling them onto the street, a chorus of “those who reflect on the state of nature and politics” reminds the audience of two portraits of the brothers: first of all “dat hoog-heerlyk stuk dat Dordrecht in zyn Raadhuis maalde” (that highly praised piece of art that Dordrecht had in its town hall), and secondly the portrait of Johan de Witt, standing in the hall of the States of Holland, as painted by Jan de Baen. Fury, according to Oudaen, had already mistreated Cornelis’s portrait, as a bleak premonition of his eventual fate, and now the real thing had happened. The chorus ends with the words: “Stand still, forget about [these] painting[s], and the disgrace or damage they suffered,” now that the theater of their real life and death is opened to us, and we see their mutilated bodies hanging upside down.17

The rhetorical appeal to forget the portraits of the brothers De Witt, obviously, intended exactly the opposite, that is, they should be remembered forever. The same play of hiding and showing, remembering and forgetting can be found in one of the medals that was struck to commemorate the brothers’ death: some copies have survived in which the image of the brothers hanging from the tree in The Hague has been sculpted on a small door that gives access to a secret vault in which other images or poems in praise of Johan and Cornelis could be kept (fig. 8).18

In the print we discussed earlier (fig. 7), Johan de Witt was identified as “maximus ille toga” (best in laws), Cornelis as “maximus ille armis” (best in arms). We find the same qualifications in a contemporary medal commemorating the brothers’ death (fig. 9). On the reverse they are shown being devoured by wild animals; the marginal text speaks of the loss of all the qualities of “that noble pair of brothers” (as in Horace, Satyrs, 2.3. 243), due to the furious mouth of the monstrous mob. In the deliberate use of the word trucidat one hears clear echoes of earlier pro-Oldenbarnevelt iconography as in Joost van den Vondel’s Palamedes ofvermoorde onnoselheyt or in Cornelis Saftleven’s Judges of the Raadpensionaris (with the text “trucidata innocentia” written on the wall) from 1663.19

With expensive, commemorative medals like these, which in their classicist and emblematic imagery were clearly aimed at a more sophisticated, and obviously pro-Wittian audience, we have traveled far from the crude and rude images of the dead bodies of the brothers and from some of the triumphant anti-Loevesteinian manifestations in lower and much cheaper media that were issued immediately after their death and that obviously aimed at a much broader (and lower class) audience.20 We find only indirect, subordinate references to their role and to their fate in more elaborate prints on the formal annulment, in 1674, of the so-called Eternal Edict of 1667, which was intended to ban the princes of Orange from the office of stadholder forever.21 Of course, this damnatio memoriae of the De Witt brothers had everything to do with the fact that the victorious Orangeists saw no reason whatsoever to commemorate opponents whom they were very glad to find taken out of their way.22 But added to that, they must have been willing to follow the admonishment issued by the States of Holland on September 27, 1672. This announced that they had decided, upon the explicit wish and recommendation of the Prince of Orange, to ordain that everything that bore upon the unrest and rebellions in recent times, whatever its nature and by whomever committed, “must be and must remain forgotten and forgiven.”23

With this explicit proclamation of what was called “a general amnesty, or complete forgetfulness” the States of Holland followed up on a policy they had earlier applied in certain provinces in the late 1620s and early 1630s in an effort to calm down emotions after clashes between pro- and anti-Remonstrant groups. They instituted the same policy in 1650, after the siege of Amsterdam by Stadholder William II.24 Already in 1623, Jan van de Velde II had illustrated a long poem in which the poet Jan Starter had called for national unity in matters of religion. The remedy for all dissension, according to Starter, had to be found in the burning of libelous pamphlets and “famous prints” in the cleansing fire of patriotic love. This would inevitably lead to more unity, even among Remonstrants and counter-Remonstrants, and to the disappearance of discord and staatzucht, a vice that can best be translated as unmeasured political ambition.25

In this climate of deliberate and officially promoted forgetfulness, of healing wounds and covering old and recent oppositions, it is no wonder that the life and death of the brothers De Witt were inscribed into a much broader, humanistic, reflective policy of remembrance. In a print, published and sold by Romeyn de Hooghe in 1675, the portraits of Johan and Cornelis de Witt function within the framework of a classic tale of rise and fall and of a deugden spiegel (a mirror of virtues) (fig. 10). While the populace engages in a long-lasting battle to outdo the memory of the brothers, the text says, this image helps us to reflect on the remarkable changes in the preferences of the people, a mirror of “al te stijf getrocken interest,” that is, of personal interest pushed too far by the De Witt brothers, and of “stoute lust om sijn selfs en de sijnen groot te maecken,” the reckless ambition to make big oneself and one’s relatives. This “mirror” by De Hooghe must be viewed in contrast to a contemporary “Orangien wonder spiegel,” also by De Hooghe, on the virtues of Prince William III.26 The same theme of staatzucht, of unbridled political ambition, in conjunction with the well-known lesson of the instability of human glory, can be found in a medal with the portraits of the brothers on one side and on its reverse the image of King Sesostris on his chariot, drawn by four prisoner kings, a premonition of the ever-changing whims of Fortune.27

Coenraet Decker’s allegory on the death of Johan and Cornelis de Witt, which functioned as an illustration to Het swart toneel-gordyn, opgeschoven voor de heeren gebroederen Cornelis en Johan de Witt, a compilation of poems and other texts on the events of 1672, may serve as the final curtain on my argument (fig. 11). Here, Time melancholically reflects on the ill fate of the brothers, whose portraits hang from a table, on which we also see a book entitled Rise and Fall of the Great, Plutarch’s Life and Death of Illustrious Greeks and Romans, and Vondel’s Palamedes (on the death of Oldenbarnevelt). The latter was that other raadpensionaris who, in the eyes of his supporters, had been the victim of Orangeist usurpation of power, and whose portrait can be seen in the background of the scene. The accompanying poem by Govaert Bidloo, an outspoken supporter of the brothers, places the whole affair of August 20, 1672, under the mild and acquiescing sign of Vanitas. Another poem on the same print in this collection calls upon Time to finally close the “theater of atrocities” from that fateful day.28

Political portraiture in the seventeenth-century Republic is constantly at play with all kinds of elements celebrating and obscuring memory.29 A portrait can be dedicated to eternity and be ripped to pieces in the blink of an eye. Portraits are contested, rejected, appropriated, and reappropriated. Vandalized portraits can be remembered (for better or for worse), serve as inspiration to kill, or function as a call to portray no more. In the heat of the moment, the interpretation of political portraits seems to be dictated by partisan, factionist politics, glorifying their own heroes and rejecting, or even ritually killing, those in opposition. Soon, however, a more reflective mode appears to set in. Fostered by the call of the authorities for a general amnesia, authors and artists try to reinterpret recent and drastic events by transforming these, and the portraits of those involved, into well-known historic and moral schemes of fortune and fate, inscribing them into the cycles of the longue durée of cultural memory and into the more concentrated, shorter cycles of political memory. To do that convincingly, some wanted to forget the more vulgar aspects of historic reality, like the atrocities inflicted upon the brothers De Witt, while others chose to transcend the vulgar by creating new historical myths and beliefs.