When Pompeo Batoni, mindful of the mystic visions of Marguerite Marie Alacoque, painted his renowned Sacred Heart of Jesus (1765–1767), he like her was engaging with a meditative visual theme that the Society of Jesus had already codified by the 1640s. This essay examines several key Jesuit and Jesuit-inspired Flemish emblem books, asking how and to what ends they visualize the mimetic-affective relationship between the Lord’s heart and the votary’s. These books present the Sacred Heart and the spiritual exercises attached to it as the highest form of image-based prayer directed at uniting the exercitant with Christ. Jesuit emblematists treat spiritual conformation as a pictorial process, and concomitantly they construe exercitants as skilled artisans whose expert manipulation of various materials secures the Lord’s likeness in their hearts.

Modern devotion to the sacred heart of Jesus dates from the last quarter of the seventeenth century, especially the 1670s, when feasts commemorating the Cor Iesu Sacratissimum began to be celebrated in northwestern France, and the 1680s, following the publication of Kasper Drużbicki, SJ’s, treatise Meta cordium, Cor Jesu.1 However, Jesuit emblematists had lavished considerable attention on the loving heart of Jesus long before then. To a great extent, the unitive practices of mystical devotion, whereby the exercitant strives by affective means to achieve full spiritual union with Christ, had migrated by the early seventeenth century from the textual domain of the treatise-cum-handbook to the bimedial—i.e., visual-textual—domain of the emblem book. The Society of Jesus played a key role in this repurposing of the emblem book. Images, actual or imagined, had long been used to focus the mind, heart, and will on the desired object of devotion. The emblem book, which consists in its classic formulation of three parts—a motto, a picture (pictura), and an epigram that comments on the relationship between the motto and the picture (the assumption being that just as words read the image, so, conversely, the image determines how those words are read)—was appreciated by Jesuit emblematists as a ready source of symbolic images that could function as both anchors and spurs to prayer. The emblematists of the Society of Jesus usually added a third textual part, a long exegetical commentary that interprets thematic connections among the other three parts.

In particular, emblematists seized on the pictura and its associated texts as virtual instruments for focusing the mind in/on prayer and for stimulating and intensifying appropriate emotional responses in the votary. Mystical spiritual exercises traditionally moved through three registers of devotion: the first focusing on penitence and purification, the second on illumination by grace of the Holy Spirit, and the third on intimate communion with the Creator. Intense feelings accompanied all three stages: remorse with penitence, grateful joy with illumination, and exalted ease with communion. Jesuit emblem books that were composed to serve as mystical spiritual programs almost always focus on the cor Iesu (heart of Jesus); they were designed to assist exercitants to conform their hearts to that of the Lord. The process of conformation, as this essay will make evident, was framed as analogous to the artisanal processes through which images are fashioned: drawing, engraving, and/or painting. By the same token, Jesuit emblematists drew parallels between pliable materials—such as copper, paper, or canvas—and the human heart to be refashioned, by means of prayer, into a living image of the cor Iesu. Achieving this likeness between the votary’s heart and the heart of Christ—or, more precisely, between the image of the former and the image of the latter—was the ultimate goal of the emblem books I describe here.

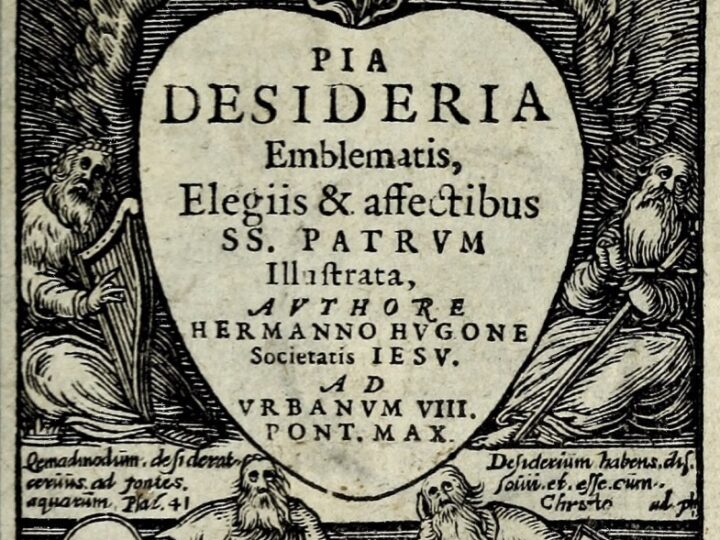

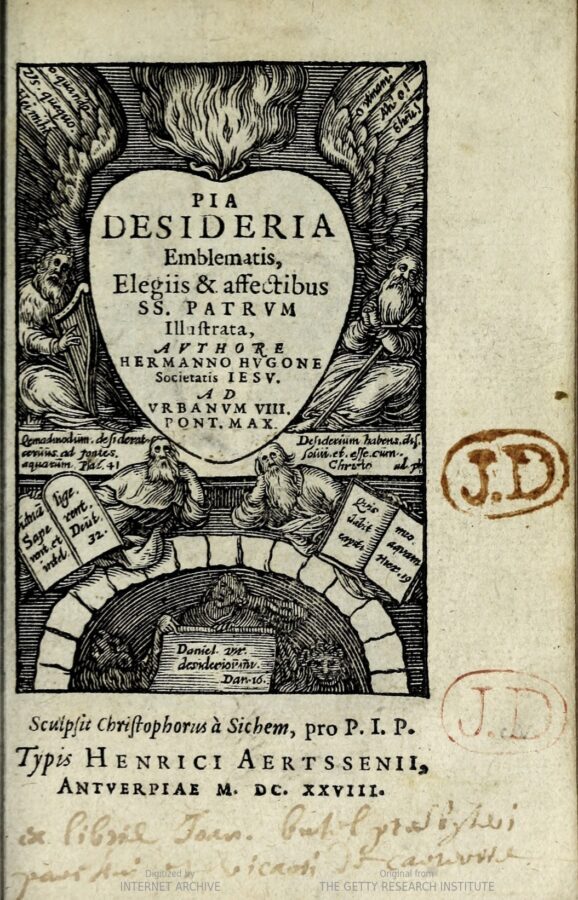

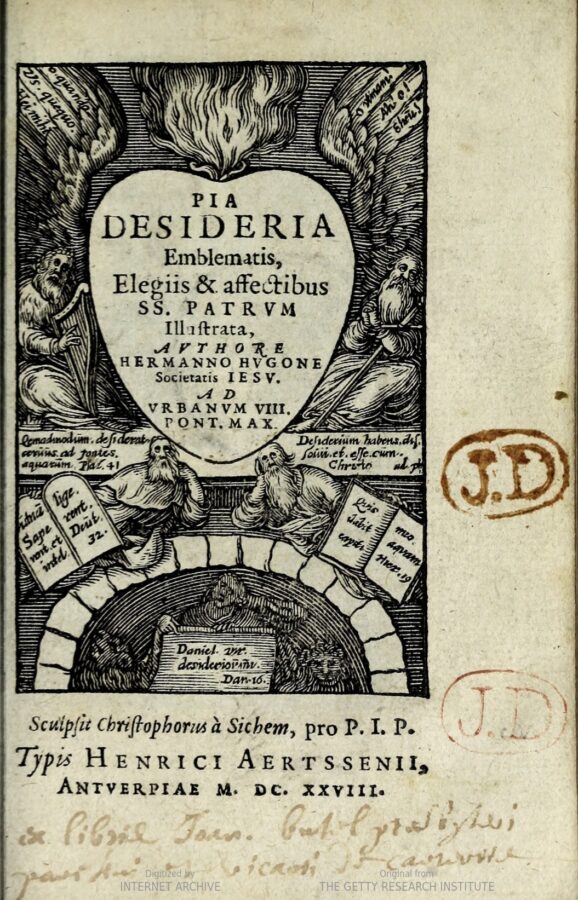

Two emblem books principally set the parameters of Jesuit devotion to the sacred heart: Jan David, SJ’s, Messis myrrhae et aromatum ex instrumentis ac mysterijs Passionis Christi colligenda, ut ei commoriamur (Harvest of myrrh and spices gathered from the mysteries and Passion of Christ, that we may abide with Him; 1607),2 the first half of his two-part emblem book, Paradisus Sponsi et Sponsae (Paradise of the Bridegroom and Bride); and Herman Hugo’s Pia desideria emblematis, elegiis, et affectibus SS. Patrum illustrata (Pious longings illustrated by emblems, elegies, and affections of the holy fathers; 1624).3 Inspired by these works, Benedictus van Haeften, OSB, adapted and further disseminated their heart emblems in his Schola cordis, sive aversi a Deo cordis, ad eumdem reductio et instructio (School of the heart, or the restoring to God and instruction of the heart turned away from Him; 1629) (figs. 1 and 2).4 These publications consist of integral series of emblems that take the form of spiritual exercises based largely on the bridal imagery of the Canticle, or Song of Songs. Composed of programmatically linked emblems centering on the mortal heart’s relationship to the cor Iesu, the Messis, Paradisus, and Schola cordis had two principal functions: they assisted reader-viewers to visualize the nature, kind, and degree of that relationship, and they guided and instructed them as they set about the task of conforming their hearts to that of the Lord.

This emblematic imagery appears to have been familiar to Marguerite Marie Alacoque (1647–1790), the Burgundian mystic whose visions of the cor Iesu proved crucial to the widespread institutionalization of devotion to the sacred heart within the Roman Catholic Church. Indeed, the visual and verbal themes explored in the heart emblem books of David, Hugo, and Van Haeften permeate the mystical visions of this professed nun whose revelations, undergone at the Visitandine convent of Paray-le-Monial, ultimately inspired Pope Clement XIII (r. 1758–1769) to ratify a feast and Mass in honor of the cor Iesu in 1765. Initially limited to the bishops of Poland and the Archconfraternity of the Sacred Heart in Rome, the feast was extended to the universal church in 1856.

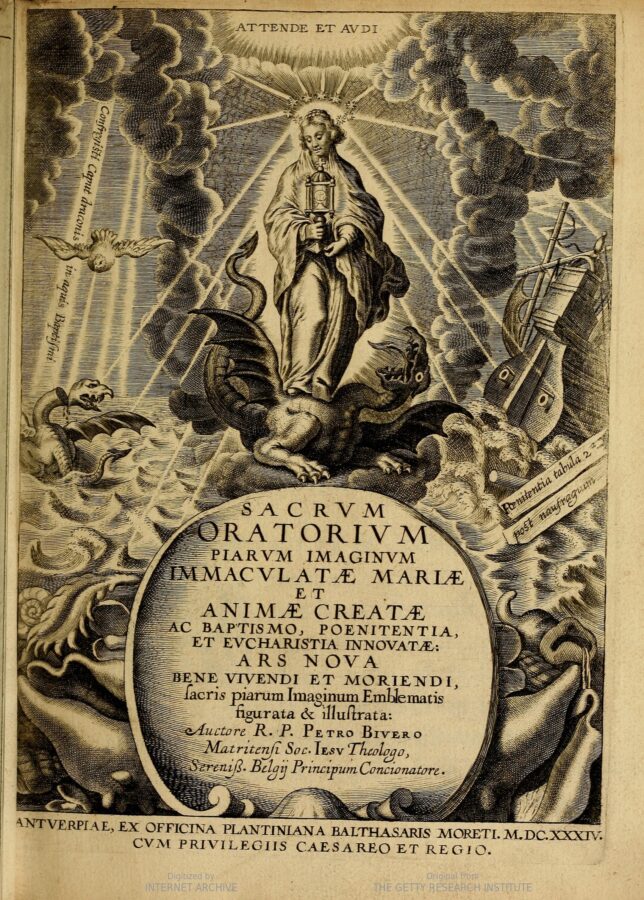

In order better to ascertain the impact of Jesuit and Jesuit-inspired heart emblems, my essay begins with a brief account of Alacoque’s visionary memoirs; more specifically, of her reliance on emblematic devices. I then turn to her probable emblematic sources, David and Van Haeften, asking how and to what ends they portray the sacred heart as the sine qua non of contemplative devotion (see figs.1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9). The second part of the essay examines Hugo’s Pia desideria, the Jesuit emblem book that codified the visual-verbal imagery of the mind/heart (mens) as the affective-cognitive source of spiritual sight (fig. 3; see also figs. 10, 11, and 12). As is typical of Jesuit emblem books, Hugo dwells on the nature of the mens both pictorially and verbally—which is to say that his emblems about the workings of the mind/heart produce an image of it in words (the emblem’s motto, epigram, and commentary), in/through the emblem’s pictura, and through their mutual interaction. His conception of mens as a God-given human faculty underlies Van Haeften’s heart emblems, just as David’s heart imagery underlies Hugo’s. Finally and briefly, I turn to the meta-reflexive heart emblems in Pedro Bivero’s lavish emblem book, Sacrum oratorium piarum imaginum (Sacred Oratory of Pious Images; 1634),5 which are as much a reworking of Hugo’s as of Van Haeften’s (see figs. 13 and 14). Written and illustrated in the Southern Netherlands, the three emblem books whose heart imagery I discuss were all produced in Antwerp, the foremost hub of Jesuit publishing, not only in Europe but worldwide.

Marguerite Marie Alacoque’s Emblematic Visions of the Sacred Heart

Written at the behest of her Jesuit director, Francis Rolin, and first published in 1726 by Joseph de Gallifet, SJ,6 Alacoque’s memoirs frame her visions as having occurred during the performance of contemplative prayer when she places her soul “before Our Lord like a blank canvas before a painter,” abandoning it to her “Sovereign Master,” who gives her “to understand that the canvas was my soul whereon He wished to paint all the features of His suffering life.”7 The trope of the self—namely, the heart—as a picture in the making derives from the emblematic tradition, where the heart’s capacity to conform itself to Christ was understood in mimetic terms as the taking on of his likeness and compared to the process of painting, drawing, imprinting, or sealing his image on oneself. Speaking to his votary Alacoque, Christ elaborates on these picturae, expounding them in statements that resemble prose epigrams; Alacoque’s presentation of her visions, centering on (verbal) images accompanied by expository texts that make sense only when read through these images, is strongly emblematic in format and function. It therefore comes as little surprise to discover that on the three major occasions (and numerous minor ones) when Jesus revealed his divinely loving heart to Alacoque, the images painted on her soul appear to derive from earlier Jesuit emblems of the cor Iesu.

Alacoque’s confessor, Claude de la Colombière, SJ, insisted that she leave a written record of these visitations. Both he and his successor, Jean Croiset, SJ, not only bore testimony to the truth of her visions but also publicized them widely, including Christ’s urgent call, vouchsafed to her in June 1675, for the establishment of a feast of the Sacred Heart on the Friday after the octave of Corpus Christi. De la Colombière and Croiset were surely the conduits through whom Alacoque became aware of David, Hugo, and Van Haeften, but it is also bears noting that the Salesian religiosity of Paray-le-monial, the Visitation convent where she resided, would have both prepared her to understand the heart emblems gathered in the Paradisus, Pia desideria, and Schola cordis and predisposed her to assimilate their message. The image-based theology of Saint Francis de Sales, who co-founded the Order of the Visitation in 1610, was central to the spiritual life of the Visitandines. Joseph Chorpenning, OSFS, has argued that De Sales viewed the human heart as the “locus of the divine image and likeness,” temporarily obscured by sin but rediscoverable and amenable to restoration by the grace of God.8 De Sales thus compared himself to a painter who fashions hearts in the likeness of his Maker; his primary episcopal task was to “paint upon the hearts of his people not only the ordinary virtues, but also God’s most dear and well beloved devotion.”9 By assisting his flock to conform themselves to the virtues of the heart of Jesus—humility and gentleness, above all—he aimed to reconstitute them as philothei/philotheae (lovers of God). Although De Sales did not codify the emblematic imagery of the heart as comprehensively as did the Jesuit emblematists or the Jesuit-inspired Van Haeften, his profoundly affective doctrine, by situating the imitation of Christ in the heart, laid the groundwork for Alacoque’s espousal of their programmatic efforts to reform the heart in the Lord’s image.

As Alacoque attests in her spiritual memoirs, when Jesus first proffered his sacred heart, he did so in two stages. To start with, he made visible the mysteries of his “burning charity,” bodying them forth in the form of a flaming heart:

Then it was that, for the first time, He opened to me His Divine Heart in a manner so real and sensible as to be beyond all doubt, by reason of the effects which this favor produced in me, fearful, as I always am, of deceiving myself in anything that I say of what passes in me. It seems to me that this is what took place: ‘My Divine Heart,’ He said, ‘is so inflamed with love for men, and for thee in particular that, being unable any longer to contain within itself the flames of its burning charity, it must needs spread them abroad by thy means.’10

Alacoque implicitly draws a distinction between the heart’s presence, painted on her soul so vividly as to be “real and sensible” in its effects, and her representation of them (“anything that I say of what passes in me”). The efficacious presence of the Lord’s heart is communicated, along with its meaning, via emblematic means—a cordiform image of fiery charity that signifies, as Christ makes plain, his desire to ignite a conflagration of redemptive love. Alacoque is identified as the spark that will fan the flames of divine love, setting her fellow Christians afire.

Second, Jesus presents Alacoque with an image of her love, picturing her heart in the symbolic form of an atom of fire absorbed into the blazing furnace of the cor Iesu and then restored to her as a heart-shaped flame. He next supplies an epigrammatic reading of this image, voiced in the first person, assuring her of his constant affection:

After this He asked for my heart, which I begged Him to take. He did so and placed it in His own Adorable Heart where He showed it to me as a little atom which was being consumed in this great furnace, and withdrawing it thence as a burning flame in the form of a heart, He restored it to the place whence He had taken it, saying to me: ‘See, my well-beloved, I give thee a precious token of My love, having enclosed within thy side a spark of its glowing flames, that it may serve thee for a heart and consume thee to the last moment of thy life; its ardor will never be exhausted, and thou wilt be able to find some slight relief only by bleeding.’11

In Alacoque’s second major vision of the Sacred Heart, received shortly after the arrival of De la Colombière as her confessor, Jesus amplifies this imagery of dual hearts conjoined: this time two hearts are shown poised to enter the burning furnace of the Lord’s heart, where they will indissolubly be united to him and to one another. As Jesus explains, the unity of three hearts in one signifies the eternal brotherhood and sisterhood of Alacoque and De la Colombière in Christ, through whom they are jointly privileged to share in the passionate fire of divine love.12 Earlier in her memoirs, Alacoque describes another emblematic image recurringly painted upon her: on the first Friday of every month, Christ represents his Sacred Heart in the form of a “resplendent sun,” its burning rays falling “vertically upon [her] heart” and so hotly that they threaten to “reduce [her] to ashes.”13 On one such occasion, while praying before the Holy Sacrament, she is visited by Jesus, who displays his wounded hands and feet “shining like so many suns”; blazing even more intensely, the heart-wound in his side emits flames that shoot out from the Sacred Heart, which is thus revealed as the true source of all these fiery tokens of the Lord’s love. Opened by Longinus’s spear, the side wound was revered in both the exegetical and meditative traditions as having bared Christ’s heart to human eyes and released the final flow of his redemptive blood. Alacoque thus writes:

Jesus Christ, my sweet Master, presented Himself to me, all resplendent with glory, His five wounds shining like so many suns. Flames issued from every part of His sacred humanities, especially from His adorable bosom, which resembled an open furnace and disclosed to me His most loving and most amiable heart, which was the living source of these flames.14

In what became the cult’s key image, Pompeo Batoni’s Sacred Heart of Jesus (1765–1767), commissioned by Domenico Calvi, SJ, to mark Clement XIII’s ratification of a feast and Mass in honor of the cor Iesu, Christ presents himself and his incandescent heart to the votary in the manner described by Alacoque: the Sacred Heart, resplendent like the sun, its rays so bright that they eclipse even the light of Christ’s aureole, illuminates the wound in his right hand, linking the vulnus cordis (wound of the heart) to the vulnera manuum and pedum (wounds of the hands and feet) but also privileging it as primum inter paria (fig. 4).15 The gash in the heart’s right side conflates the side wound with the wounded heart of Jesus, and the crown of thorns wrapped around the heart’s ventricles, along with the cross rising from the flames discharged by the two uppermost valves, emphasize that his fiery love burns nowhere so brightly as in his Passion. As Alacoque declares: “It was then [i.e., in putting his five wounds on view] that He made known to me the ineffable marvels of His pure [love] and showed me to what an excess He had loved men.”16

From Blood to Fire: Alacoque’s Adaptations of Jesuit and Jesuit-Inspired Emblems of the Sacred Heart

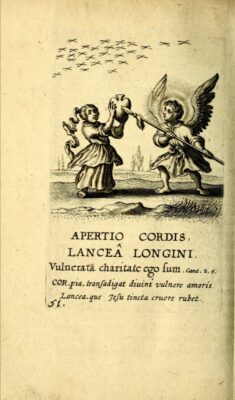

The Jesuit and Jesuit-inspired emblems that codified the imagery of the cor Iesu and took stock of its principal themes align closely with Alacoque’s usage throughout her memoirs, differing only in one important respect. Whereas the emblems analogize the showing forth of the Sacred Heart to the flow of holy blood that pours from the five wounds of Christ—springing, above all, from his heart pierced by Longinus’s lance—the Sacred Heart as envisioned by Alacoque surges outward in a torrent of luminous fire. That this fire was seen as a metonym for blood is evident from the way Batoni later painted the ruby-red flames bursting from the Sacred Heart; he gave them the same base color as the blood-soaked organ from whence they spring (see fig. 4). The orange highlights on the tongues of flame not only reflect the yellow of the refulgent rays but are in fact mixed from the heart’s red and the rays’ yellow, as if from a convergence of blood and fiery light. Alacoque, in adapting the imagery of blood to the imagery of fire, retained the emblematists’ key themes. The emblems visualize the heart as an illimitable source of grace that erupts from the depths like a flood or spillage of blood; Alacoque visualizes grace as a holocaust, as fast-burning and superheated as holy blood is immersive and fast-flowing. The structural principle underlying her imagery of fire is consonant with the emblematists’ imagery of blood. Indeed, in book 4, lesson 12, emblem 51 of Van Haeften’s Jeusit-inspired Schola cordis, titled “Apertio cordis lancea Longini” (Opening of the heart by the lance of Longinus), the blood of Christ is said to have flowed so hotly that it both stained the spear red and ignited it with the fire of the Savior’s love (fig. 5). In his commentary on the relationship between the emblem’s pictura, which depicts the Spirit of Divine Love piercing the votary’s heart held aloft by Anima (the votary’s soul), and the emblem’s epigram—“The good lance, which grows red, tinted by the blood of Jesus, pierces the heart with the wound of divine love”17—Van Haeften ascribes to the image, if properly meditated on, the power to inflame even the coldest heart with the love of Christ: “O how I wish that with body uninjured you would transfix my soul with that same lance, and wound my heart salutarily with the sharp point of your love: for this lance has the power to ignite my cold heart with the fire of love.”18

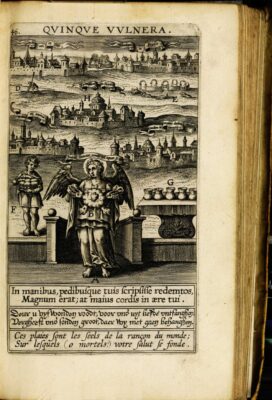

Emblem 46 of David’s Messis myrrhae et aromatum, titled “Quinque vulnera” (The five wounds), likewise develops the theme of the Lord’s purifying blood; inflamed by the fiery lance, it pours forth from Christ’s breast, made visible and accessible to us as if in an igneous stream (fig. 6). The pictura centers on an archangel (A) holding a cloth imprinted not with the Holy Face but with the five wounds of Christ (B); the implication is that the wounds show the Lord to us as forthrightly as the sudarium (the “sweat cloth,” also known as the veil of Veronica, which was impressed or—as early modern viewers would have put it—imprinted with his face), on which we see him, so to speak, facie ad faciem. Above the angel flutters a banner inscribed with an excerpt from Isaiah 55:1: “All you that thirst, come to the waters.” To the left, right, and in the distance are six typological manifestations of the Lord’s saving love: the fountain/river from which flowed the four streams that watered paradise, figurative allusions to the heart as the source of the blood that streamed from the other four wounds (C; vide Genesis 2:6); the five smooth stones chosen from the brook by David (D; vide 1 Kings 17:40); the five porticos of the healing pool of Bethesda (E; vide John 5:2); the five barley loaves that miraculously fed the multitude (F; vide John 6:9); the five cities awarded to the servant who quintupled his master’s pound (G; vide Luke 19:19); and the five joys experienced by the blessed in heaven—joy in the presence of God, of angels, and of saints, and joy in one’s soul and in one’s perfected body (H). David, commenting on the relationship between the pictura and the epigram—“Great it was to have written upon your hands and feet those [you] have redeemed, but greater still to have written them on the copperplate of your heart”19—interprets the wounds, the side wound most of all, as openings onto the Lord’s heart and doorways into the sanctuary of his “good thoughts.”

If we bare our hearts to the fiery lance of his potent charity, states David, those thoughts will pass from him to us:

Shall I therefore not see the good thoughts of [His] heart through the fissures of [His] body?. . . The secret sanctuary of the heart lies open through the holes of the body. . . . Who, Lord, thus wounded would not love you? Who would not return love for love. . . . Wound [my soul] with the fiery and most potent spear of your most formidable charity.20

In anticipation of Alacoque, David imagines the Sacred Heart projecting outward, from within Jesus toward the worshipper. As the exposition of the Sacred Heart inspired Alacoque to suffer lovingly with Christ and share in his Passion, so David imagines the Lord’s heart piercing the votary’s heart, wounding as it was wounded, thrusting through like the lance that first exposed his own heart to human eyes. The votary’s heart, thus penetrated, is set alight, nourished, and amplified by the love of Christ, in fulfillment of the biblical types gathered in the pictura. Addressed to Jesus, the epigram’s notable reference to the “copperplate of your heart,” draws an implied parallel between the Sacred Heart and a copperplate engraving. This simile originates in the scriptural image of Christ impressing his seal on the faithful in 2 Corinthians 1:22—“Who also hath sealed us, and given the pledge of the Spirit in our hearts”—and also from such acheiropoieta (icons divinely made rather than with human hands) as the sudarium, miraculously imprinted by Christ with his Holy Face. Just as a copperplate, once cut by a master engraver, can imprint an image, so (implies David) the heart of Jesus has the power to imprint itself on us, converting us into living images of him, as expressive of his love as he.

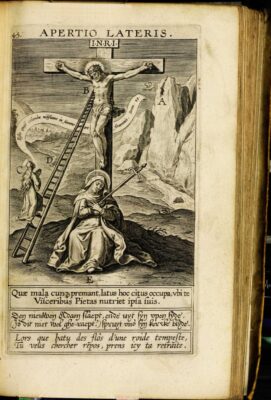

For Alacoque as for David, the love engendered by contact with the Sacred Heart is at once visceral and spiritual: in chapter 71 of her memoirs, for instance, Alacoque records how the spiritual effects of grace that the Sacred Heart produced in her soul and heart resulted from the privilege of pressing her lips to the wounded heart of Christ for two or three hours.21 In emblem 45 of David’s Messis myrrhae et aromatum, “Apertio lateris” (Opening of the side), the epigram reads, “Which evils, whensoever they oppress, speedily occupy this side [wound], whereby His innermost organs that selfsame love will nourish you.”22 Reading the image by way of the epigram (and vice versa), David calls on the votary to imitate the bride of Christ prophesied in Jeremiah 48:28: “And be ye like the dove that maketh her nest in the mouth of the hole in the highest place” (fig. 7). The votary, flying upward like the dove or, rather, climbing up the cross (A), will take hold of its stem (B), crawling through the Lord’s feet and up his torso (C), using the nails as handholds, as if ascending the rungs of a ladder (D). Reaching the side wound, the votary will place their mouth against the wound’s mouth, drinking from the bloody waters of salvation at their source (namely, the heart of Christ). From here, every aspect of the cor Iesu, even its most secret parts (“omnia interiora cordis”) will be made known in a showing forth of divine mercy.23 David declares in a closing prayer that the Sacred Heart, brought to view, will make the Lord’s mercies as apparent as his miseries on the cross; in exchange, we must show him the many and various miseries we elect to suffer on his behalf: “As many, Lord, are the miseries of the body, so many, too, are the mercies of your heart; give us, we pray, to show you the abyss of our misery, that you in turn may show us the abyss of your mercy, and we may experience the effect of your salvation.”24

Picturing Properties of the Cor Iesu in Van Haeften’s Schola cordis

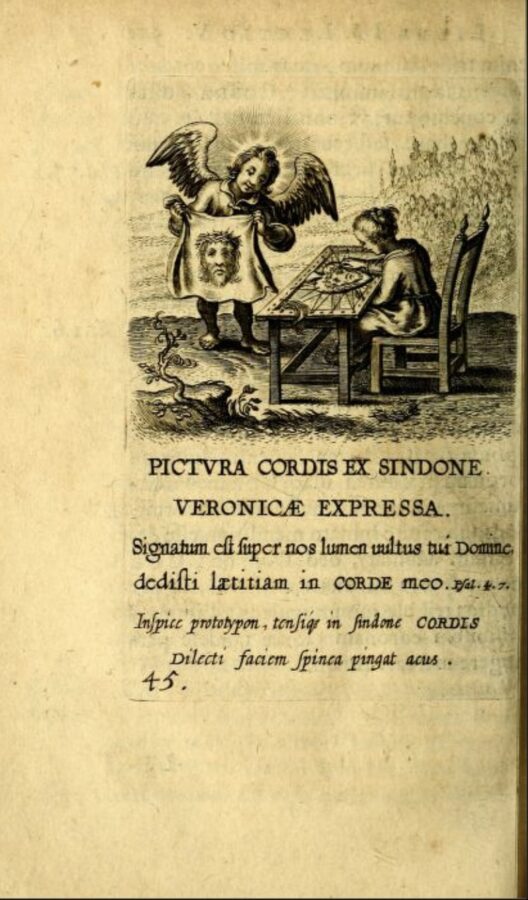

Alacoque’s sense of Christ as a painter who limns an image of his heart on her heart—or alternatively, presents his self-image for her to limn—most likely derives from Van Haeften. Throughout the Schola cordis, he pays close attention to the picturing properties of the Sacred Heart and its influence on the votary whom it empowers variously to envision the love of Christ. In book 4, lesson 6, emblem 45, “Pictura cordis, ex Syndone Veronicae expressa” (Picture of the heart, expressed from the veil of Veronica), he explores how the heart’s images are given and received (fig. 8). Based on Psalm 4:7—“The light of thy countenance, O Lord, is signed upon us: thou hast given gladness in my heart”—emblem 45 revolves around a picture of the Spirit of Divine Love displaying the Veronica veil to Anima, who copies its features on her heart, in the form of a cloth (tela) held taut by threads woven through a stretcher laid flat on a worktable (the bundled thread ends hang loose at the upper left corner). She draws, paints, or embroiders—Van Haeften’s choice of verbs such as adumbrabo, pinget, and punget (respectively, I shall represent in outline, paint, or prick, in the sense of stitch) allows for multiple possibilities—with a thorn extracted from the crown of thorns lying on the ground beside her chair. The conceit of portraying the heart as if it were outside the body, as an impressible surface open to artisanal manipulation, visible to the eyes, and workable by the hands, emphasizes that the heart can be remade in the image of Christ.25 The process of pictorial imitation stands for the empathetic process of entering fully into the Passion of Christ, so that mimesis becomes indistinguishable from co-suffering. The epigram instructs the reader-viewer to join Anima in thus reworking the heart contemplatively: “Observe the prototype, let the thorny needle/sharp-pointed stylus embroider/paint/picture the face of the beloved stretched out on the veil of the heart.”26

Recourse to a plethora of material and artisanal analogies allows Van Haeften to make his case that the votary’s heart, if it is to merge with Christ’s heart, must become indistinguishable from the Holy Face, no less an epitome of his Passion than this greatest of relics. So, in response to Psalm 44:13—“And the daughters of Tyre with gifts, yea, all the rich among the people, shall entreat thy countenance”—he advises reader-viewers that if they wish to retain a proper image of the Holy Face, they must imprint it on their hearts as if on the softest wax (“tamquam mollissimae cerae”). He then moves from the process of sealing to that of engraving, enjoining the reader-viewer to engrave a living likeness of the Holy Face on the hard, flinty stone of the heart in order to mollify it (“schulperetur in filice cordis mei viva effigies serenissimi vultus tui”). Then, enriching this analogy, he instructs the reader-viewer to use the nails of the cross like burins (caela), writing or incising (literally, ploughing) with them on the metal plate of the heart (“clavi illi . . . efficerentur mihi caelum, quo profundissima exararem, incideremque te in lamina cordis mei”). The term profundissima puts an accent on the depth of cut necessary to impress the heart with Christ. By the same token, the votary’s heart is compared to a cloth stretched on a loom prior to weaving or on a frame prior to embroidering, or to a canvas likewise stretched and ready for painting:

But who is this Apelles who portrays this [picture] for me in living colors? Who are the Zeuxis and Parrhasius who will imitate with a skillful hand these lineaments impressed upon Veronica’s veil? I myself am he, if there be no one else, who shall undertake the work of every kind of painting and, looking at the face of my Christ imprinted on the sudarium, shall represent the same in outline, in Phrygian filigree, to what degree I am able. But where is the needle/sharp-pointed instrument? Where the finely woven cloth? Where the parti-colored threads? A thorn from your crown, made purple by your blood, will be for me a stylus (radio) and needle, as often as I pierce the cloth of my heart, painting the same in rosy blood; nor will a finely woven cloth be necessary, since I may be permitted to weave one from the hairs plucked from your sacred head and venerable beard.27

Summarized at the end of Van Haeften’s commentary, the multiple media and techniques whereby the cordiform image of the Holy Face may be pictured indelibly on the heart (“indelebilis est pictura”)—sculpted clay in low relief (“luto laminae sculptura”), sealed molten wax (“emollita cera aut novo impresso signaculo”), an image drawn or painted with a reed pen or small brush (“quae calamo fit aut penicillo”), and/or an inscription engraved in high relief (“eradi possunt altissimae caelatae litterae”)—guarantee that this cordiform facies will remain there for as long as the reader-viewer lives, lodged deep within the heart (“stabit quamdiu Cor stabit”).28

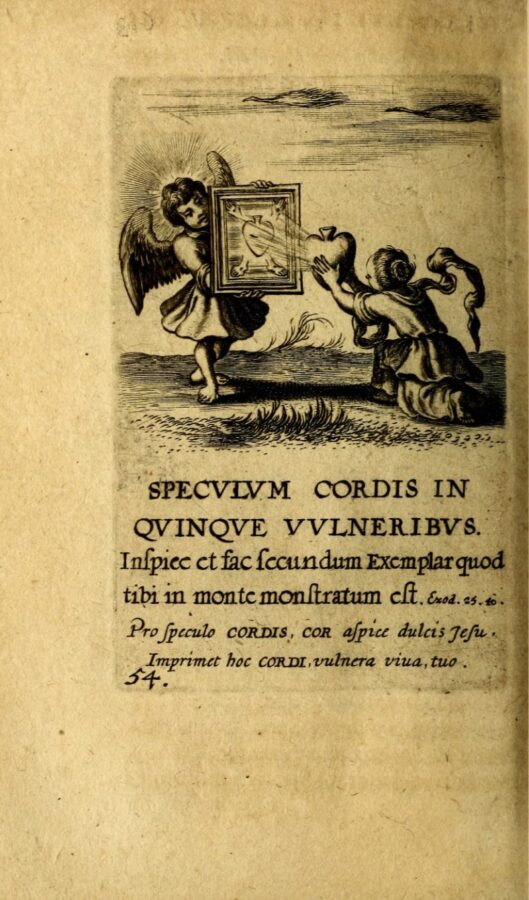

Book 4, lesson 15, emblem 54, “Speculum cordis in quinque vulneribus” (Mirror of the heart in five wounds), most closely approximates Alacoque’s account of the action of the Sacred Heart on her person (fig. 9). As Christ presents his wounded heart to her, prompting her to recast herself in the likeness of his Passion, so in emblem 54, we see the Spirit of Divine Love projecting Christ heart’s image forward to Anima, by means of extromitted rays that transmit it, conjoined with the other vulnera Christi (wounds of Christ). Drawn from Exodus 25:40—“Look and make it according to the pattern, that was shewn thee in the mount”—the epigram frames the process we see unfolding in the pictura as one of imprinting: “Behold the heart of sweet Jesus as the mirror of [your] heart; it will imprint his living wounds upon your heart.”29 In showing his heart to Anima, Christ impresses his wounds on her heart, causing it to encompass the fullness of his suffering and thereby to become veritably indistinguishable from the Sacred Heart. Although there are two ways of reading pictura 54—as the extromission of the Lord’s heart or as the intromission by Anima’s heart of the image projected by the Lord’s heart—both readings ultimately prove to be one and same. The spirit’s mirroring heart and Anima’s, folded into one, become inseparably laminated. As Van Haeften puts it in his commentary: “You, O our Savior, as if a mirror of virtue and an upright picture, have put forward in yourself, for all who wish to cultivate piety, a certain image clearly expressed, the example of which all persons (each like unto himself) may transfer to their life, by inspection of your lineaments.”30 Jesus’s ardent love, set in projective motion by the mirror of his wounds, after the fashion of a ray reflected by the votary’s heart (“radij instar evibratus et a Corde meo reflexus”), is made to burn most brightly (“luculentissime accendatur”) by this exchange of hearts.

The mysterious process of heartfelt giving and receiving, emblematized by Van Haeften as a kind of double mirroring (radiating from the mirror of the vulnera Christi to the receptive mirroring heart of Anima), set the pattern, widely circulated with the Society of Jesus and beyond, for the type of reciprocal exchange later described by Marguerite Marie Alacoque between the Sacred Heart and her own heart. Her reward for bearing fervent witness to the cor Iesu, as her memoirs testify, was the privilege of reliving his Passion in every particular; his suffering heart and hers become wholly conformable. On a first Friday of the month, for example, while the divine heart was being opened to her, she heard Jesus say: “I will make thee share in the mortal sadness which I was pleased to feel in the Garden of Olives, and this sadness, without thy being able to understand it, shall reduce thee to a kind of agony harder to endure than death itself.”31 Like the emblematic protagonists of David’s Messis myrrhae et aromatum and Van Haeften’s Schola cordis, she is given to see the heart of Jesus or, better, takes its image, so that in seeing him, she sees perfected a fiery reflection of herself.

Mens (Mind/Heart) as a Locus of Spiritual Discernment in Hugo’s Pia desideria

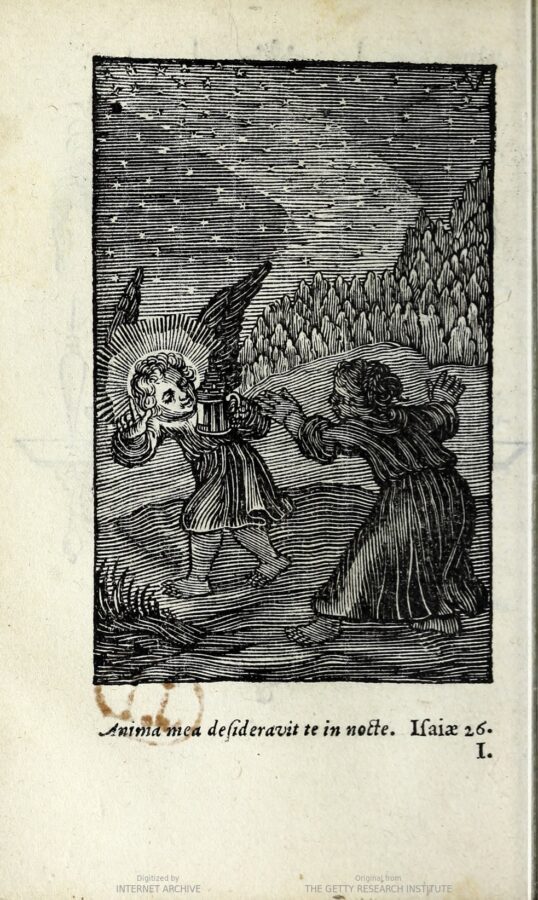

As noted at the start of this essay, Van Haeften’s conception of the mind/heart (mens) as an affective-cognitive source of spiritual sight derives from Herman Hugo’s Pia desideria (fig. 3a). Inspired by the Pseudo-Augustine’s Soliloquia and Meditationes32 and Otto van Veen’s Amoris divini emblemata (1615),33 the Pia desideria consists of a tripartite sequence of forty-five emblematic spiritual exercises. On the title page, the term vulgavit identifies Boétius à Bolswert not only as publisher but also as illustrator, whose images “put forth the book universally to the world.” By the time Van Haeften penned the Schola cordis, Hugo’s Pia desideria was well on the way to becoming the most widely read and printed of all Jesuit emblem books.34 The first fifteen emblems, styled gemitūs (groans), urge reader-viewers to consider their sinful condition; the second fifteen, renamed vota (vows), encourage them to renew efforts to draw closer to Christ; the final fifteen, now called supiria (sighs), track the votary’s final approach to Christ, the object of desire, to whom by stages, in parts 1 and 2, they had conformed mind, heart, and spirit. Two related emblems from Pia desideria—emblem 1 of book 1, “My soul desired you in the night. Isaiah 26,” and emblem 21 of book 2, “Let my heart be undefiled in thy justifications, that I may not be confounded. Psalm 118”—provide good examples of Hugo’s understanding of mens, which might best be translated “heartful mind” or “mindful heart.”35 The first emblem opens book 1, which is purgative in argument and tone (“First Book of the penitent soul’s sighing”; fig. 10); the second emblem forms part of book 2, which is illuminative (“Second Book of the holy soul’s desirings”; fig. 11).36 The theme of emblem 1 is the darkness of spiritual obscurity that enwraps any soul unlit by the light of Christ; that soul finds itself trapped in nighttime gloom so dense that even though it desperately longs to see Jesus, no part of him appears visible, least of all his loving face. The motto, taken from Isaiah 26:9, reads: “My soul hath desired thee in the night.”37 The pictura depicts the first encounter between the book’s two mystical protagonists—a winged male spirit whose boyish features adumbrate those of Jesus, understood by Christian biblical scholars to be the bridegroom of the Song of Songs; and a young girl who bodies forth Anima, the soul longing to become the Savior’s bride. Their childlike qualities, in addition to signifying the innocence and purity of their stepwise relationship, also connote the malleability of Animus, who constantly adjusts himself to the needs of Anima, and conversely her willingness adapt herself to his presence and grow into her role as bride. But Christoffel van Sichem I’s woodcut, far from simply illustrating their chance meeting, turns it into a conundrum of sorts. The nocturnal scene is faintly lit by the glimmering light of the Milky Way (visible as a gray band that curves across the starry sky), and the Jesus-like spirit illumines his own face with a lamp, but Anima remains very deeply shadowed, darker than anything else around her. Furthermore, the spirit’s presence seems to have startled Anima: arms outspread, she casts her hips backward as if recoiling, and her umbrous eye, seen in profile, looks too shaded to return his gaze. Her gesture registers shock more than it reaches to embrace. In what sense, then, can she be construed as the desirous soul prophesied by Isaiah?

The long epigram gradually clarifies what is going on here. It opens with Anima lamenting her inability to pierce the shadows that envelop her so thickly: they are “murky, ashen, leaden, sinister, and abhorrent” to such an extent that even the “odious lairs of hateful Dis, where dusky night is said to have her home” cannot compare.38 She continues, “By night, that populace of Dis sees the night of the dead, and the Cimmerians see that they are devoid of light,” whereas “cruel fate has damned me to never-ending shade where not even an iota of sidereal flame glitters.”39 Her night is darker than night and so impenetrable that it exceeds even the absence of light. Up to this point, halfway through the poem, Anima has heaped hyperbole on hyperbole, describing the dark circumstances that fatally frustrate her desire to lay her eyes on Christ. Then, suddenly, the poem shifts: we learn that these circumstances originate in Anima herself; they are symptoms of her moral failings, manufactured by her darkling self-love, by her pride and worldly ambition, which have fashioned the all-encompassing image of night that now totally subsumes her spirit. Her mens (mind/heart) is, by her own admission, the originating source of the imago that has somehow become the actual night of her trapped soul:

And nor (which is wont to be a comfort to the blind)

Does that selfsame mind/heart, fit to be pitied, see its night.

But verily it loves its own shadows; loathing the light,

It turns toward the shades of ominous night.

To be sure, Pride having robbed the spirit of its flames,

Clouds over with its darksome robe the blind lights of the eyes.

Ambition does not suffer the bright sun to shine,

And with the fire of Idalian Venus it blackens the [eyes’] noble torches.

Alas, as often as the image of night stealthily enters me,

So often does black night assail my spirit.40

Because Anima’s darkness is self-generated and comes from within, Van Sichem portrays her as darker than her nighttime ambience, and since her desire for the bridegroom fails to curtail her ingrained love of self-made shadows, she is shown as more startled by than welcoming of Christ.

Having recognized that recalcitrance is the source of her sorry condition, Anima launches into a series of questions that leads eventually, at the poem’s close, to the dawning of a change of heart. The first of these questions incipiently acknowledges that she has blindly led herself astray: “What effect has reason, what effect has the eager will, what have they when the mind/heart is wayward as to its twin guides?”41 The “guides” are Anima’s paired eyes, dimmed if not completely blind, and, as such, symptomatic of spiritual blindness. The reparative exercise of reason, in the form of further telling questions, now emboldens Anima’s dormant faculty of will. She first imagines how it would be to live close to the easternmost place where Apollo (the sun) rises and to long for his rising; or how it would be to look up at the polestar with eyes uplifted toward Olympus. What she would exclaim there and then is what she should cry out now, calling on Jesus to show his face and bestow some small part of his light. And even if he should choose, for whatever cause, to withhold his light, nevertheless her resolve to express her desire for him—to will that he be present—would suffice to confer some measure of consolation:

And very often have I said: Shine, shine, my Sun!

Sun who for many a days has been unadored by me!

Arise, arise, and at least stretch forth half [your] face;

Even a sole scintilla of yourself can suffice.

If still you deny me the use of this much light,

It will be enough to have desired your face.42

The pictura offers an assurance that the spirit of Jesus will not reject Anima: he shines a light on his own face and, pointing upward, indicates that looking at him is tantamount to looking at God. The prose commentary appended to the emblem justifies this reading. Citing book 7, chapter 10, verse 16 of Augustine’s Confessions—“When I first knew you, you lifted me up, that I might see that there were things for me to see, but that I myself was not yet ready to see them”—Hugo explains that through the mystery of the Incarnation, we became like coins stamped with the image of Christ, who is the image of God. His flesh was thus the lamp that illuminated us by the Word of God, making manifest our likeness to him and causing us to cultivate this similitude.43

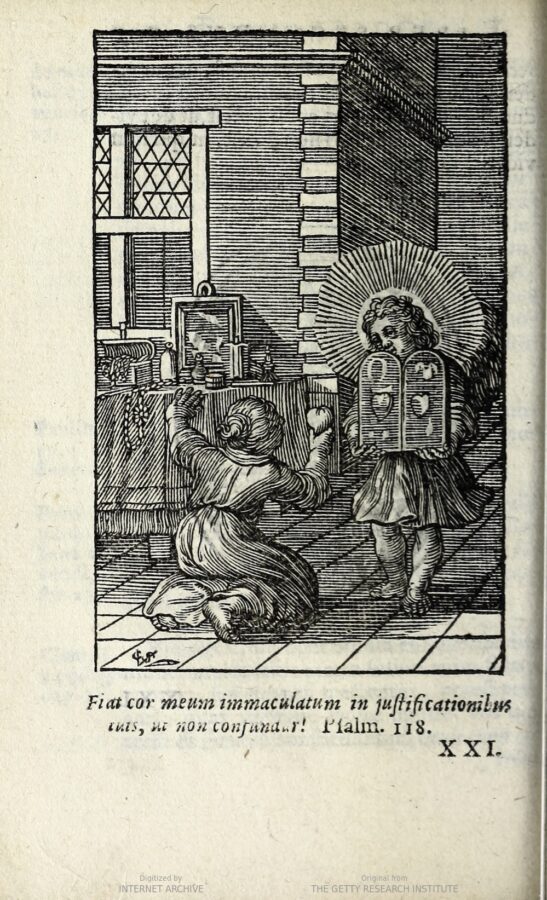

Emblem 21, the sixth in the illuminative sequence, responds to emblem 1, showing how far Anima has come since then. Although her face is still shadowed, she reacts far more positively to the presence of Jesus the bridegroom, kneeling reverently at his feet and, most important, offering him her heart (see fig. 11). She holds it aloft where, brightly lit, it marks the transit of her gaze toward the tablets of the law held open before her by Jesus. The tablets function like mirrors, each panel reflecting a cordiform image of Anima’s gift, with further bright highlights reflected above and below. The mirrored hearts also mark the position of Jesus’s heart, as if the image of Anima’s outstretched heart is coincident with his. At the same time, Anima, with a gesture of her raised left hand, repudiates the framed mirror leaning face forward on the dressing table amid the accoutrements of an elite woman’s morning toilette. The motto, taken from Psalm 118:80, reads: “Let my heart be undefiled in thy justifications, that I may not be confounded.”44 Read in tandem, the pictura and motto imply that Anima, justified in God—i.e., purged of sin—has rejected the mirror of temporal vanities in favor of the mirror of the law, wherein, through keeping the commandments, she lays eyes on an image of her heart’s conformation to Christ’s heart. The degree of conformation is so great that in looking at the mirrored hearts that signify her heartfelt affection, she jointly sees a bipartite, affectionate image of the Sacred Heart being tendered for her benefit.

The epigram, a poem in thirty-three couplets, supports and elucidates this somewhat daedal reading. The poem’s first half is ironic; it focuses not on the mirror of the law but on the mirror sitting on the dressing table and on the extravagant, futile efforts of women who use such mirrors to prettify themselves for their lovers. Like one of these women, Anima misconstrues what it is that Jesus, her would-be bridegroom, will find attractive about her: “If I should reckon to please you with [my] face, bridegroom, / it should be by labor and care of the face.”45 And so, “too anxious about her looks” (“nimium formae . . . studiosa”), she endlessly searches for brightly colored cosmetics, for purple-red rouge and white Cretan earth, for ruddy foam of natron and Poppaean cream, with which to conceal even the smallest spot. As Anima puts it: “Then, too, with the mirror as judge, I might correct the blemishes, / So that in all [my] face there be not the tiniest fault.”46 Suddenly, halfway through the poem, the memory of the things Jesus truly values deflects her from her futile efforts to primp and preen, as if she were vying with the three goddesses once judged by Paris.47 Beauty such as theirs, she now admits, is as superficial as it is deceptive:

But I recall: neither face nor form excites you,

This invidious hope lays hold only of blind suitors;

Who often search amongst superficial ornaments for what they desire,

Which once removed, what part remain to you, Virgin?

The capricious mob is as good as duped by a false complexion;

And beyond these outward trappings, they hold nothing dear.48

The poet, speaking in the voice of Jesus, instead enjoins Anima to emulate Saints Wilgefortis, Lucy, Euphemia, and Andragesina, who scorned bodily blandishments so greatly that they chose on occasion to disfigure themselves. Anima, therefore, calls on Christ to free her heart of every disfiguring mark made through contravention of the law. (The reference is to Mosaic law as renewed by Christ in Matthew 5:17.) Equating beauty of heart with the face God desires to see, she declares:

Bridegroom, you are neither seized by the fire of an exotic figure,

Nor well deceived by the art of crimped locks:

The heart free of stain, the heart without reproach, is dear to your heart;

And may the heart stand forth, like a face, pleasing to you.49

The Anima of emblem 1, formerly obscured by sin, barely visible even to herself, now reveals herself to her bridegroom, showing him a face/heart shorn of cosmetic artifice and freed of adventitious ornaments. The distinction between the earlier and the later Anima drives home the contrast between a soul needful of purgation and a soul partially or wholly illuminated by the Lord. The prose commentary underscores the reference to emblem 1, making the spiritual contrast between the two emblems perfectly clear. It, too, turns on the contrast between bodily ornament and spiritual beauty: to obsess on the former is ridiculous in that humankind, “made in the image and likeness of God,” shows itself ready “to overlay inferior human artifice onto the artifice of God, as though mocking the exemplary Archetype.”50 In defense of this point, Hugo quotes extended passages from the works of the ancient Greek comic poets Antiphanes and Alexis, who satirize the preoccupation with superficial good looks and juxtaposes to them an excerpt from Clement of Alexandria’s Paedagogus, which, apropos of Isaiah 53:2 (“And we saw him, and he had no comeliness or beauty”) asks: “But who is more admirable than the Lord? Although he displayed true beauty of the spirit and the body, not beauty of the flesh (which is perceived by vision): beneficence of soul; in truth, immortality of the flesh.”51 Then, recalling her former dark condition, as exemplified in emblem 1, Anima recursively acknowledges that the traces of that darkness linger, that her maculated appearance is still wont to displease the Lord, but also, in closing, fervently attests her determination to purify herself of every imperfection and remove every moral blemish that offends God. Emblems 1 and 21, like other paired and tripled emblems across the three books of the Pia desideria, are thus presented as compactly linked (see figs. 10, 11):

O, how much there is in me, on account of which I blush before his eyes, and by cause of which already I fear more to displease him than trust that through those things fit to be praised in me (if there be any) I should be able to please! O, would that I could hide by some small degree from his eyes until I had wiped away all these stains and might, at last, appear immaculate in his sight, without any blot! For how shall I please him, owning this deformity by which I, too, vehemently displease myself? O, ancient stains! O, stains loathsome and foul! Why so long do you sit fast? Leave, depart, and presume no more to aggrieve the eyes of my beloved.52

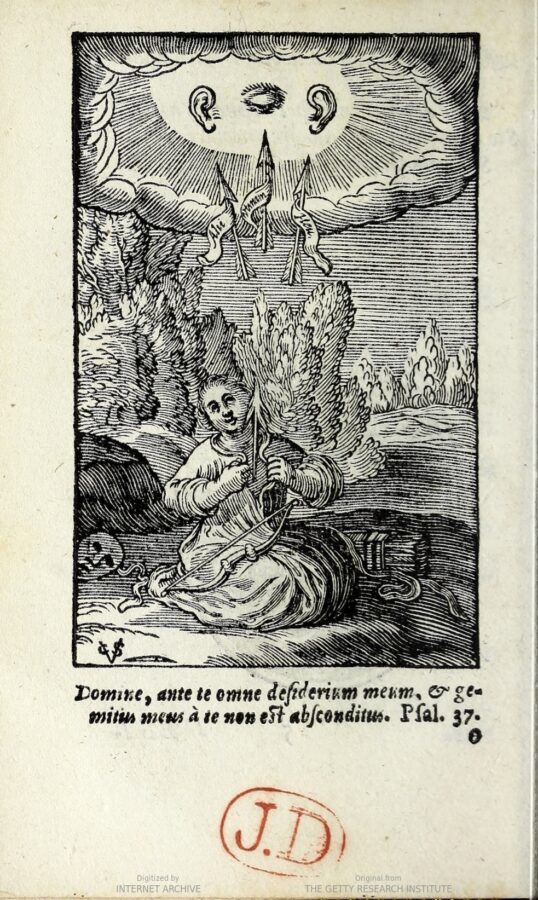

In support of my point that the Pia desideria, like so many other Jesuit emblem books, was composed to function as a densely woven intertext, it is worth noting that the frontispiece sets the context for Hugo’s entire emblematic sequence (fig. 12). The theme of this emblem is the nature of the prayerful conduit between prayer and God. Although the poet’s remarks pertain to all three kinds of prayer—purgative, illuminative, and unitive—here the emphasis falls especially on penitential prayer. Anima, the poem’s speaker, opens with an admission: her anxious mind/heart secretly burns with silent longings that she could never willingly disclose to any other person. Were there anyone capable of discerning her hidden groans and sighs or of tempering her plaints by giving ear to them, that person’s healing art would perfectly tally with her desires, but no such person exists. And so, like Rachel mourning her slain children in Jeremiah 31:15, she weeps beyond comforting, but, unlike her, conceals her weeping in the manner of a fire that, devouring its embers, reveals no flame, or of rainwater reabsorbed into the clouds from which it rained down.53 The impulse to conceal is itself a vice, confesses Anima, who compares herself to a skillful stage actor:

O, how often does the player spirit bring forth fictive parts,

And the eyes and brow gainsay her feelings!

While the dark mind/heart groans and suffers tragedies,

More often than not, the comic mime Roscius prances in the face.

No trust is there in tears, tears are taught to simulate,

And feigned features cover sorrow with jests.

. . .

Dissemblers have more visages than you, Proteus,

Vows with which they wear a mask, and snatch away their own.54

Seeing the penchant to deceive as an epitome of the human condition, Anima asseverates, halfway through the poem, at its crux, that only God has the power to pierce this penchant for masking, for only he is party to the soul’s every hidden wish, silent lament, and covert sight. “None except he and I alone know” such things, says Anima, who affirms this truth three times to lay stress on it.55 And the last line of the poem asserts, as regards her “groans, sighs, and desirings” (“gemitus, suspiria, votaque”), that no one other than he and she know them, and that, mutually paired, these two suffice unto themselves.56 The reference to deception implicitly acknowledges that the mind/heart, if it is indeed like a picture—painted, drawn, printed, or sealed—can produce either a true or false image of God. To ensure that its cordiform surface registers a true likeness, the reader-viewer must be guided by Hugo’s emblematic spiritual exercises, keeping pace with the sequential program they lay out.

The poem comments on the relationship between the epigrammatic motto taken from Psalm 37 and the pictura, which shows Anima seated on the ground amid her characteristic possessions: a mask that signifies her propensity to dissimulate, its removal thus signifying her desire to go unmasked before God; and a quiver stuffed full of arrows, which intimates, along with the strung bow resting on her lap, that she hunts intrepidly for the things she desires. Indeed, she gazes heavenward and bares her heart, releasing a fiery arrow of desire aimed at the radiant eye and ears of the Lord. Hovering above her, three other arrows, aimed respectively at the eye or one of the ears, carry banderoles inscribed with the interjections “Ahi” (Alack!), “Utinam” (Would that), and “Heu” (Alas!). The first and the last are penitential, whereas the middle one, in the subjunctive, is hopeful, and as such, shades toward the illuminative. The epigram quotes Psalm 37:10: “Lord, all my desire is before thee, and my groaning is not hidden from thee.” Two other verses from the same psalm implicitly inform the picture: the arrows are a reversal, in direction, content, and tone, of the arrows of divine retribution described at 37:3: “For thy arrows are fastened in me: and thy hand hath been strong upon me.” The arrows are also symbols of the hope professed at 37:16, “For in thee, O Lord, have I hoped: thou wilt hear me, O Lord my God.” Together, the motto, pictura, and poem-epigram function exegetically, for they constitute a reading of Psalm 37, the meaning of which is presented as a summa of the nature and scope of the tripartite spiritual project laid out by Hugo in emblems 1–45 of his emblem book. The frontispiece emblem adumbrates the topic of emblem 1, Anima’s inclination to hide her true nature, as also the topic of emblem 21, her showing forth of her mind/heart to God, whom the dedicatory title that prefaces the poem-epigram (and the recapitulation of the motto) on fol. **6r–v identifies as Christ. The title runs: “The Man / Husband of Longings, to the object of desire of the eternal hills, Christ Jesus, at whom the Angels desire to gaze, [and] to the object of his Love and Desire.”57 The lesson one learns by working through this emblem, and brings to one’s reading of the series of emblems that follows, is that divine knowledge of one’s intentions of mind and heart, since it is both total and ineluctable, must necessarily be embraced and reciprocated.

“Cordiform Conformation of the Human Heart to the Sacred Heart in Bivero’s Sacrum oratorium”

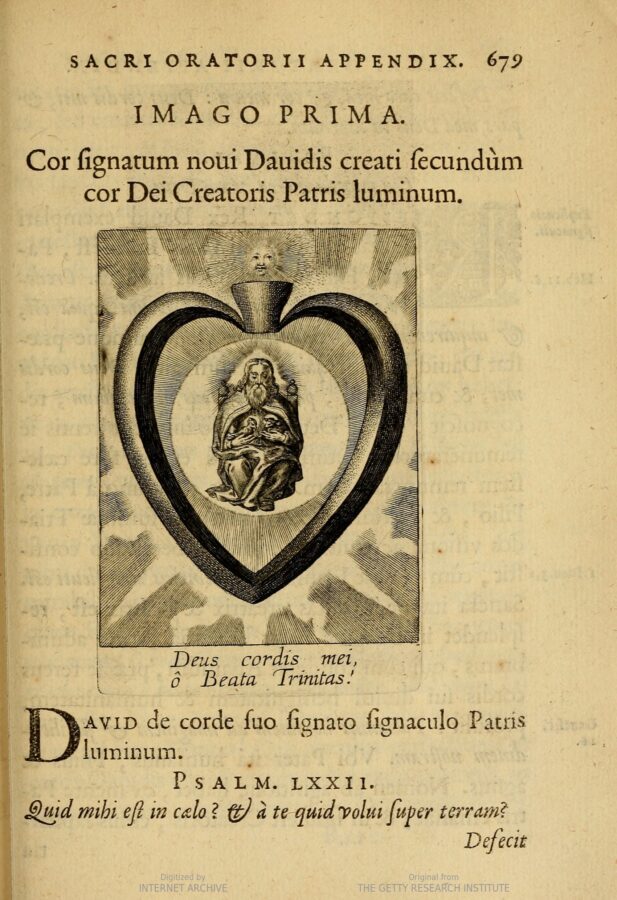

Finally, let us turn to an example of emblematic heart imagery based on David, Hugo, and Van Haeften. The fourfold architecture of Petrus Bivero, SJ’s, massive emblem book Sacrum oratorium piarum imaginum, published by the Plantin Press in 1634, is uncommonly complex, as the full title indicates: Sacrum oratorium piarum imaginum immaculatae Mariae et animae creatae ac Baptismo, Poenitentia, et Eucharistia innovatae: Ars nova bene vivendi et moriendi, sacris piarum Imaginum Emblematis figurata et illustrata (Sacred oratory of pious images of the immaculate Mary and the created soul renewed by baptism, penance, and the Eucharist: The new art of living and dying well, figured and illustrated by sacred emblems of pious images; fig. 13).58 Designed by Adam van Noort and engraved by Adriaen Collaert and/or Karel de Mallery, the engraved plates that anchor the fifty-seven chapters would have been subject to close examination by Bivero, as had been the case with earlier emblem books produced by the Plantin Press. Although imago is Bivero’s preferred term for the pictures that populate the Sacrum oratorium, he uses it in a highly reflexive fashion in part 1 and systematically grafts qualifying terminology to describe the distinctive form and function, manner and meaning of the pictures in parts 2–4. In the baptismal Marian allegories of the first part, they are called imagines or tabulae; in the penitential allegories of the second part, they are termed either parabolae or tabulae, but the latter term is now inflected differently; in the Eucharistic, bridal allegories of the third part, they are either insignia or signa; and in the abstracted heart allegories of the fourth part, which functions as an appendix, they are signacula traced in a cor signatum. I want to examine briefly the first heart emblem in Part 4 (fig. 14) .

The final part of the Sacrum oratorium, “Appendix piarum imaginum cordis novi Davidis secundum cor Dei Creatoris, Redemptoris, et Sanctificatoris” (Appendix of pious images of the heart of the new David in accordance with the heart of God the Creator, Redeemer, and Sanctifier) is designed to help the reader-viewer visualize their heart sealed by Christ (figs. 13 and 14). The soul thus sealed, pictured in fifteen emblems, is presented as the fulfillment of the prophecy in Psalm 4:7: “The light of thy countenance O Lord, is signed upon us: thou hast given gladness in my heart.” The emblems are said to portray the heart of the new David—that is, of the votary baptized, absolved, and nourished by the sacraments, who performs spiritual exercises as fervently as David prayed the psalms. The votary can now be shown as incorporated into the heart of God. Cultivation of the cordiform images comprised by the Appendix is construed as indistinguishable from the worship of God and complementary to full participation in the sacramental mysteries. With respect to the appended imagines, Bivero adjures:

Let the images appear of the heart of David revering his Creator.

Let the mysteries appear of the soul created and renewed.

Attend in your heart the sign/seal/signet of the likeness of God.59

The reference to the sealed heart paraphrases Ezekiel 28:12: “Thus saith the Lord God: Thou was the seal of resemblance, full of wisdom, and perfect in beauty.”

The fifteen heart emblems, since they purport to reveal heartfelt processes of spiritual coalescence taking place deep within the new David, and since their imagery of perfected hearts is both hypothetical and aspirational (this is what you can and should achieve by working through the Sacrum oratorium, promises Bivero), consist of more rarefied constituent elements than those in parts 1–3. Each of the emblems’ components is a representative symbol, a figurative element such as a simile, metaphor, metonym, synecdoche, personification, or catachresis (the use of such a figure in a deliberately unconventional way). Take the imago prima and its two motto-epigrams (see fig. 14): above, “Cor signatum novi Davidis creati secundum cor Dei Creatoris Patris luminum” (Sealed heart of the new David created according to the heart of God the Creator, Father of light); below (engraved on the plate), “Deus cordis mei, o Beata Trinitas!” (God of my heart, o Holy Trinity!), the opening line of the Eucharistic hymn “O sacrum convivium.” The epigrams declare that David’s heart is sealed with the image of the luminous heart of God; the imago prima merges the two hearts, making them veritably indistinguishable . God, in the words of Psalm 72:26, is the “God of my heart,” possessor of and possessed by the heart he has sealed/impressed/imprinted (“cor signatum”). The heart is thus heard to enunciate, in the voice of the Spirit speaking through David, Psalm 72:25–26:

David [speaking] from his heart signed/sealed with the signet of the Father of light [or alternatively, with the signet of the Father’s light].

Psalm LXXII.

“For what have I in heaven? And besides thee what do I desire upon earth? For thee my flesh and my heart hath fainted away: thou art the God of my heart, and the God that is my portion forever.”60

Throughout the Appendix, the imagines cleave closely to the format of the imago prima: a radiant heart encloses a symbolic image alluding to the sacramental presence of God, with a device signifying the Trinity—the sun for God the Father, the lamb for God the Son, the dove for God the Holy Spirit, a flame for God the Son offered as a holocaust—hovering above the valve of the heart.61 In the imago prima, the central image shows God the Father enthroned in heaven, holding in his lap the Son in the form of a lamb and the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove. He enfolds them within his mantle to indicate that Son and Holy Spirit are encompassed by the Father. The lamb and the dove can also be read in light of two of Christ’s parables. As an allusion to the lost sheep in Matthew 18:12–14 and Luke 15:3–7, the lamb invites us to think of God as the Good Shepherd; if the dove is seen as a chick and thus an allusion to the protective mother hen in Matthew 23:27 and Luke 13:34, it invites thoughts about God’s maternal affection toward us. Section 1 of the imago prima, titled “Psalm L: ‘Cor mundum crea in me Deus’” (Psalm 50: “Create a clean heart in me, O God”) and subtitled “Explicatio signaculi” (Exposition of the signet) in a marginal gloss, explains that the image depicts how David “responds to the pattern of his Creator, who is the triune God, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”62 It thus distills the meaning of Psalms 50 and 72, the relevant passages from which Bivero has just quoted.

For Bivero, as for David, Hugo, and Van Haeften, the heart both receives images and produces them, sees and is seen, and its processes of image-making are what enable a practiced exercitant to refashion one’s self truly, lovingly in the image of Christ. Codified by Jesuit emblematists such as David and Hugo, the heart imagery that anchored the Society of Jesus’s devotion to the cor Iesu permeated the cult of the Sacred Heart. Van Haeften then adapted and disseminated this imagery widely. Marguerite Marie Alacoque, the cult’s saintly proponent, was herself expert in these devotional practices, which in turn informed the cult image created by Batoni under the guidance of Domenico Calvi. Produced and published in Antwerp, the artistic center of the society’s Provincia Flandro-Belgica (Flemish-Belgian Province), the emblem books of David, Hugo, and Van Haeften place the cor Iesu and the cor amantis Iesu (heart of the lover of Jesus) in dialogue as mutually picturing hearts. Cordiform images are the currency of their abiding affection.