This article originally appeared as “Kunstbezit in Leiden in de 17de eeuw” in Th. H. Lunsingh-Scheurleer et al., Het Rapenburg: Geschiedenis van een Leidse gracht, vol. 5b, (Leiden: Rijksuniversiteit Leiden, 1990), 3–36. The larger publication comprises eleven volumes on the architecture, interior decoration, residents’ histories, and contents of the houses in this section of the Rapenburg, from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century. Fock’s chapter centers on art owned by collectors and others living on Leiden’s famous canal—their professions, social status, the kinds of art that they had in their possession, and the positioning of those works within their households. Works have been identified with the aid of auction catalogues and public notarial inventories.

The unequaled production of paintings, especially in the province of Holland during the Dutch Republic, is a direct consequence of the presence of an important market that included broad layers of the citizenry. The frequently cited statement by John Evelyn1 on the occasion of his visit to the Rotterdam fair in 1641 that even peasants were buying paintings, often as an investment, should be taken with a degree of skepticism. Nevertheless, the walls of many Dutch city dwellings were adorned with paintings. In most cases, this art ownership can be considered part of the customary decoration of interiors, indicative of the citizens’ increasing wealth in the seventeenth century. In this respect, the term “art collector” would be justified in only a few cases, and a clear distinction between art collectors and those owning paintings as “household effects” remains blurred in the seventeenth century.

With a wave of migrants from the Southern Netherlands and the concomitant revival of the city’s textile industry, Leiden became the second-largest city in Holland after Amsterdam. The growing trend of adorning the home with examples of Dutch painting was clearly reflected there. Local artists and the art market responded avidly to this increasing demand. Homeowners on the Rapenburg, but also elsewhere in town, often welcomed visitors into their homes, allowing them access to their works of art. As public art collections did not exist, such visits were the main opportunity for art lovers to view and study works of art.

We have a reasonably good idea of the importance of private art ownership within the Leiden city boundaries in the eighteenth century. Most art collections were not inherited upon the owner’s death, but were publicly auctioned. Preparations for these auctions sometimes even started during the owner’s lifetime, or else conditions were recorded in the deceased’s will. Therefore, many collections are described in auction catalogues, a great number of which have been preserved. Frits Lugt’s Répertoire des catalogues de ventes2 records fifty-seven catalogues of art auctions held in Leiden in the eighteenth century, mostly in the second half of the century, and eight more in nearby Zoeterwoude, where, especially during the last quarter of the eighteenth century, most owners chose to hold their auctions to avoid the taxes imposed by the city of Leiden. Moreover, four Leiden art collections went under the hammer elsewhere, three in Amsterdam and one in Haarlem.3 The auction catalogues that have been preserved are undoubtedly just the tip of the iceberg, as is clarified by other sources. The painters’ guild persuaded the city council in 1685 to agree that, upon any sale of paintings, which they saw as a threat to their own business, it was owed a compensation of three guilders.4 The resulting records of such sales indicate, more or less accurately, 212 sales of paintings held in Leiden in the eighteenth century, of which 105 were held during the first half of the century, a period for which Lugt could cite no more than nine auction catalogues.5

Newspaper announcements also point toward a much greater number of auctions than might be surmised from the remaining catalogues.6 Still, the primary Leiden collections certainly do figure into the remaining catalogues. A relatively significant number—twelve—concern Rapenburg homeowners.7 Among these, the De la Court collection was the most prominent (Rapenburg 65 and 6), while the equally high-quality collection of Pieter Cornelis van Leiden (Rapenburg 48), which was initially sold at auction in Paris in 1804 and is not included in the aforementioned numbers, was also a typical eighteenth-century collection.8

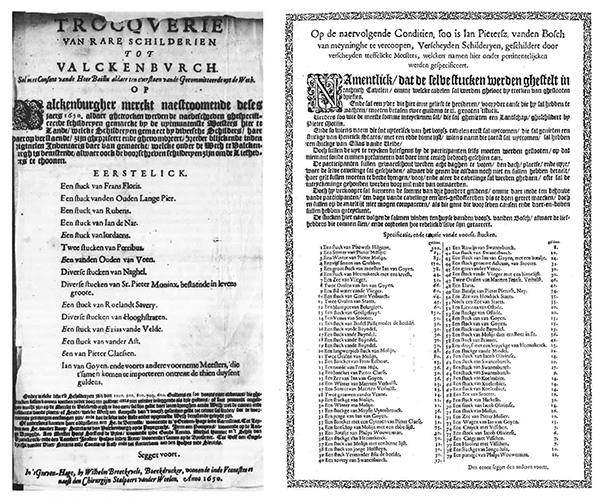

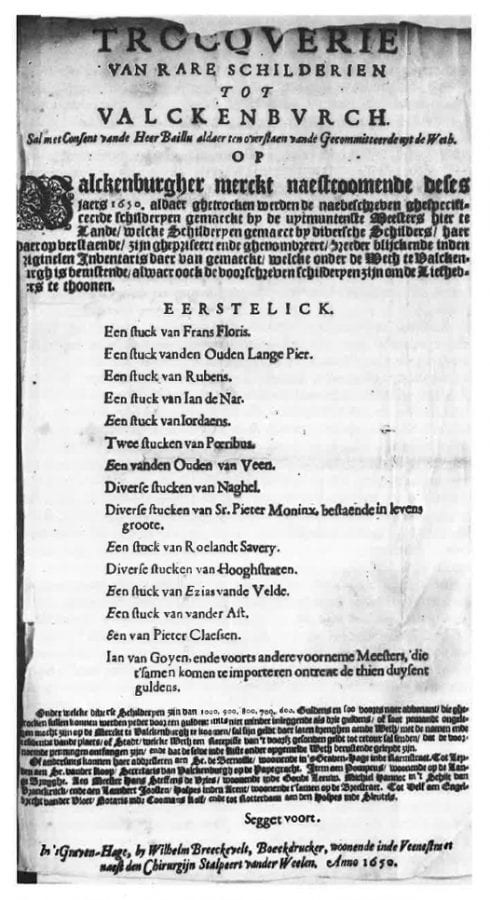

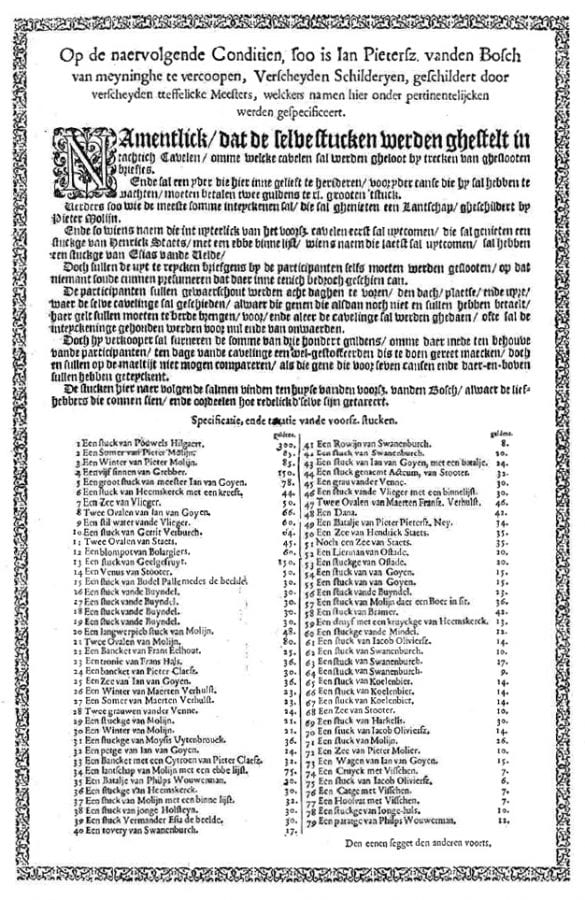

Unfortunately, auction catalogues do not provide us with a true reflection of art ownership in Leiden in the seventeenth century. The main reason for this is that auctions were not yet as well established in Holland as they became in the eighteenth century.9 Lugt only mentions three auctions taking place in Leiden, including the earliest remaining catalogue in Holland, that of Leiden apothecary Christiaen Porrett, whose collection of mainly natural specimens, curios, and ethnographic objects was put up for sale on March 28, 1628, at his home “De Dry Coninghen” in Maarsmansteeg. The other two auctions that took place in seventeenth-century Leiden—both no earlier than the 1690s—did not feature any actual painting collections but a cabinet of coins and medals and a collection of antique sculptures, coins, and medals. In addition, it listed a pair of portraits of learned men by Karel Heydanus (Rapenburg 65).

In order to form an idea of art ownership in Leiden at the time, one must consult other sources, particularly the inventories of household effects drawn up by notaries when either spouse passed away, especially when underage children were involved. Such inventories, generally our main source of information regarding home decoration in this period, have been preserved in abundance. But these were, of course, drawn up for different purposes than eighteenth-century art auction catalogues were. The latter sought to describe the works as well as possible, mentioning the artist’s name, the subject, and usually the dimensions—information recorded, for the most part, by competent artists or art dealers. By contrast, the descriptions in seventeenth-century household inventories were only meant to aid the allocation of the inheritance. In only a very few cases when a valuation was required were such descriptions drawn up by an artist. Often the inventory mentions just the number of paintings, and occasionally the—easy to establish—shape or color of the frame.

Because of the great number of inventories listing unspecified paintings, it is quite unclear whether or not some serious art collectors have passed under the radar, though these are precisely the art lovers who would have appreciated decent descriptions of the paintings they possessed. But it was hardly necessary to draw up an inventory for every death. Moreover, not all Leiden notaries’ archives have been preserved. Nor have the Weeskamer (Orphans’ Chamber) archives survived; these were another depository for a great number of inventories. The obvious lacunae in our knowledge are clearly illustrated by the case of Matthias van Overbeke, a German who was living the high life at Rapenburg 65–67. In May 1628, Arnout van Buchel saw paintings by Rubens, Bailly, Van Coninxloo, Porcellis, van de Velde, Savery, and Vrancx at his place. Van Overbeke showed himself to be a real art collector when, a couple of years later, he purchased fourteen manuscripts from the famous humanist library of Willibald Pirkheimer, some of which were even illustrated by Albrecht Dürer. Yet nothing was found in any deeds registries, either regarding van Overbeke’s art collection or regarding the rest of his home decoration.

Despite these objections, household inventories with useful data about paintings are invaluable. They offer an extensive source of general information about art ownership in Leiden in the seventeenth century—about the choice of painters, preference for certain subjects, and the size of the property. They also inform us about important collectors. Based on a selection from the available source material, this chapter will paint a picture of seventeenth-century art ownership in Leiden. It will also provide a clearer framework for the art ownership of the inhabitants of the Rapenburg, who were quite active in this respect. This selection—twelve inventories from each decade—was made in such a way as to guarantee an optimal distribution over the whole period. Also, for each decade, the most interesting inventories were selected with respect to the number of works mentioned, the number of subjects specified, or the number of times the artist’s name is mentioned. The combination of these criteria does not, by definition, favor the largest collections, but rather those that yield the most detailed data and best elucidate developments in the course of the seventeenth century.

This is just a sample survey—selected as representatively as possible, not from the various social layers of the population but focusing on the art collections themselves. Nevertheless, the growth of this phenomenon in the course of the century is immediately self-evident. The numbers of paintings per decade are quite illustrative of this growth.10

| Years | Total number | Average number | Minimum per collection | Maximum per collection | Number of names | % Names |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1600/09 | 171 | 14.2 | 3 | 35 | 2 | 1.17 |

| 1610/19 | 289 | 24.1 | 9 | 46 | 9 | 3.11 |

| 1620/29 | 524 | 43.7 | 18 | 77 | 33 | 6.30 |

| 1630/39 | 674 | 56.2 | 24 | 99 | 74 | 10.98 |

| 1640/49 | 798 | 66.2 | 36 | 142 | 207 | 25.94 |

| 1650/59 | 834 | 69.2 | 43 | 173 | 311 | 37.30 |

| 1660/69 | 1394 | 116.2 | 49 | 237 | 591 | 42.40 |

| 1670/79 | 1117 | 93.1 | 45 | 173 | 329 | 29.45 |

| 1680/89 | 933 | 77.7 | 29 | 151 | 270 | 28.94 |

| 1690/99 | 1070 | 89.2 | 53 | 264 | 304 | 28.41 |

| 1600/99 | 7804 | 65.0 | 3 | 264 | 2130 | 27.29 |

Clearly, the average number of paintings kept increasing, and there was an absolute high point in the 1660s, with an average number of items for the selected inventories higher than 110, a number that fell slightly after that. Also, each separate collection kept growing. Analysis of each separate collection shows that in thirty-eight out of 120 cases, they consisted of seventy-five paintings or more: eight of them in the years leading up to 1660, and the other thirty after that date. Most of these thirty-eight households owned between seventy-five and one hundred paintings; seven owned between one hundred and 150 paintings, six between 150 and two hundred paintings, and two collections held far more than two hundred works of art. In the largest fifteen collections (those consisting of more than one hundred paintings), most of the paintings date from the second half of the seventeenth century. Just one of them, the collection belonging to mayor Jan Jansz. Orlers, dates from1642, with 142 paintings. The collection of Jean François Tortarolis (Rapenburg 24), comprising 173 works, dates from 1656, and the other thirteen all date from the 1660s or later.

In contrast, hardly any serious collecting occurred at the beginning of the century. Art ownership in this period should still be considered just an aspect of home decoration. Regarding quantity, the selected inventories do not vary much from what was found in the average citizen’s dwelling. It is difficult to draw any general conclusions on this subject, for clearly whole swaths of the population, such as day laborers and unskilled workers, owned so few possessions that hardly any household inventories were drawn up. But in those Leiden inventories known to us, on average about five paintings are mentioned as early as the second half of the sixteenth century. This is a number that increased to eight or ten11 in the seventeenth century. Just how generalized art ownership was in all layers of the population is illustrated by the 1654 inventory of the possessions of cloth-maker Cornelis Louwerisz. He was admitted to the Saint Catherine’s hospital, and in his room two paintings—an Ontbijtje (breakfast still life) and a Fruitage (fruit still life)—were designated as “dewelcke de kinderen voor haer drinckgelt gecocht hebben” (which the children bought with their allowances).12 The spectacular increase, starting in the 1620s, in people’s appetite for much greater numbers of paintings in their homes—quite obvious from the most significant Leiden inventories—must have been one of the main reasons why, practically simultaneously, an increasing number of painters became active in Leiden. The guild was officially founded in 1648—even if it was hardly worthy of the name, as it only stipulated rules for the sale of paintings and the protection of artists who were living in Leiden while practicing their craft. Nevertheless, their numbers increased so much that in the year of its founding alone, sixty-five members registered. It is certainly not a coincidence that the high point of Leiden collecting, in terms of quantity and size, occurred in the 1620s, the years during which, as a result of its favorable economic situation, the Leiden population also reached its highest level.13

Individual Owners

So who were these people? Where was the bulk of this art ownership? Given the modest nature of the present sample survey, obviously no generalizations can be drawn. There is one observation we can make, however: we should look not only at the urban elite. City council circles were, of course, an important group of art owners. Eleven of the aforementioned 120 were members of the Leiden town council, and if we add to those some other important administrative functions, such as bailiffs (two), sheriffs (three), city clerks, and some administrative functionaries in The Hague, we are talking about twenty-three people in all. But a town official such as the verger Quirijn Jansz. van Stierevelt (collection inventory of 1659) may also deserve a mention. The fact that by virtue of his office he must have dealt with—enforced—sales of personal properties may have had something to do with this.

But the largest group of art owners was active in the business world: eighteen merchants—their areas of interest are not specified, though many of them must have been in the textile business—and four more whose occupation has been explicitly established as textile merchants. It is hardly surprising that many players in the textile industry, which was responsible for the city’s economic boom, were in a position to, and wished to, indulge in the luxury of a sizable accumulation of art. Besides the aforementioned textile merchants-cum-manufacturers, this group also comprised a greinreder or camlet (woven fabric) manufacturer. The hosenverver, or trousers dyer, Tobias Moeyart, who lived at Oude Rijn (1643) also owned sixty-four paintings, and two more dyers in the 1670s may be added to the test group as owners of, respectively, ninety-six and 103 paintings. Certainly not all merchants had to do with Leiden’s most important industry, however; for example, we also find three wine merchants and two booksellers in the test group. With 172 paintings, the bookseller Jan Jansz. Van Rijn (1668) on Gravesteen possessed one of the six largest collections in Leiden—the pictures hung all over his house—although it is possible that he was in fact an art dealer, for booksellers often sold prints and sometimes paintings as well. When he passed away in 1666, the printer and bookseller Jean le Maire, a resident of Pieterskoorsteeg, turned out to own seventy paintings; he was one of the wealthier citizens of Leiden, as he owned several houses both in the city and elsewhere. In his case, these paintings were definitely not a part of his stock: there were paintings hung not just in the hall, but mainly in his salon, in the main kitchen, in his so-called “Roman room”—after the series of twelve portraits of Roman emperors in this room?—and even in the printer’s shop.

A defining feature of Leiden, of course, is the presence of the university. It attracted many learned individuals, students, and affiliated professionals. But for the most part, they were a fleeting population of temporary inhabitants. Only a small group of individuals, including the professors, established themselves for longer periods or remained in Leiden indefinitely. Still, among the 120 people selected for this study are three professors and Festus Hommius, administrator of the theological college (1633). The collection of professor and medical doctor François de le Boe Sylvius (Rapenburg 31) was one of the five most important collections we were able to trace, with 173 paintings. It is also striking that two vicars and one of the churchwardens of the three main churches held more than seventy-five paintings in their dwellings.

Representing the liberal professions are a notary, two lawyers, two medical doctors, two surgeons, two pharmacists, and Pieter Cornelisz. van Boekenburg, historian of Holland. Jean François Tortarolis (Rapenburg 24), a banker of Italian descent who managed to turn the Leidse Bank van Lening [Leiden lending bank for goods on deposit] into a flourishing business and become very wealthy in the process, also owned an important collection. One of the most powerful urban professions was that of the brewer. Among the 120 selected art owners, two or three were brewers.14 Hendrick Bugge van Ring, whose collection of 237 paintings must have been the second-largest in Leiden, also belonged to a family of brewers. Both his grandfather and his father had owned breweries in Delft. Bugge van Ring was a Catholic, as was Gillis van Heussen Steffensz., who had no detectable occupation and owned a collection of 190 paintings at his home, the Hof van Zessen (Rapenburg 28b). As outlined by Prak with regard to the eighteenth century,15 the rich Catholic families, who were barred from public office, were for that very reason most eager to follow the example of the aristocracy and to invest their wealth in the estates and lifestyle associated with the well-heeled. Both Bugge van Ring and Gillis van Heussen fit this prototype. Both owned an estate just outside Leiden— Torenvliet in the domain of Valkenburg and Achthoven in nearby Leiderdorp, respectively—both decorated to a standard of luxury and fashion that was exceptional for the period, and their art collections are in second and third position, surpassed only by the collection of Isaac Gerard (1698) in seventeenth-century Leiden.

Then there were the innkeepers, who also owned large numbers of paintings in their establishments. These included, for example, the inn outside the Witte Poort (1627), Den Ouden Landsman in the Noordeinde, which belonged to Isaeck Jouderville,16 and the rear Doelen (1653) and the Herenlogement near the Burcht (1684). As far as can be established, these works of art were distributed over the various halls and rooms at the inns. It is uncertain whether these were collected according to the innkeepers’ personal taste, or whether financial considerations17 also played a part and the art was seen as merchandise, with the innkeeper acting as an intermediary. It is noticeable, on the other hand, that innkeepers’ household effects were often subject to estate sales, either forced or not, as was the case with the female innkeeper of the rear Doelen, Elisabeth van Montfoort, in 1653. Her estate, which included fifty-two paintings, was sold on her behalf to the pharmacist Cornelis Beeckel. Earlier, the property of innkeeper Julius Lefebre (1641), including forty-six paintings, was sold on behalf of the verger to the painter Carel van Schouten. The forty-three paintings belonging to innkeeper Cornelis van der Lucht (1657), as well as his furniture, were sold to the owner of the brewery den Eenhoorn to settle van der Lucht’s debts. One of the most important inventories kept out of the selection was one belonging to an innkeeper, Pieter de Grient (1656) who owned fifty-one paintings. But innkeeper Aernout Eelbrecht of the Herenlogement certainly was not in any financial trouble, as the real estate he owned in Leiden included, besides Rapenburg 20 (from 1661 until 1681), three other buildings as well. After his demise in 1681, his ninety-four paintings were appraised by the painter Karel de Moor and divided between his son Thomas and his son-in-law Matthijs van der Eyck, who succeeded him as innkeeper at the Herenlogement.

A significant group within the selection are people involved with the building trade, such as three brick manufacturers and two owners of a lime kiln. It is unclear in some of these cases whether they managed these manufactures and ovens themselves or just invested in them. Zeger Huygensz. van Campen (Rapenburg 3) definitely was active as a brick manufacturer. His collection of thirteen pieces in 1604 hardly exceeded the average. The same was true of the eleven-piece collection of carpenter Anthonis Martshouck (1614), who lived at Houtmarkt. But the roofer and plumber Bruyn Cornelisz. van Couhorn, who lived at Steenschuur—one of the most prosperous streets in Leiden—had twenty-six works of art in his home as early as 1628. The other brick manufacturers and chalk burners owned fifty to sixty paintings in the 1650s and 1660s. Haesgen van Rijn, the widow of town council member Jan Meyndertsz. van Aeckeren, who owned 107 paintings (1668), owned a brick manufacturing business at the Wadding near Voorschoten. But it remains unknown whether the deceased husband had personally involved himself with the business—his father had also been a council member in Leiden.

More modest artisans can be found mainly in the first decade of the selection: for instance, a shoemaker and a button maker, both in 1604, and also an embroiderer (1606) and a cutler (1607), whose painting collections did not exceed thirteen pieces, and a confectioner in 1616 who owned twenty paintings. But the tanner Quirijn Jansz. van Boschuysen at Hooigracht owned as many as thirty-eight paintings in 1623. The two goldsmiths on the list were significantly wealthier: Jan Jansz. van Griecken’s widow owned eighty-seven paintings when she died in 1657, and Johan van Werckhoven and his first wife owned fifty-six works in 1693. Both these men were among the most eminent representatives of their craft.

And finally, there is the group consisting of artists themselves and people with related occupations. In addition to quite large quantities of their own works, they owned many paintings by other artists. In 1628, besides eighteen of his own works, mainly landscapes, painter Aernout Elsevier owned twenty-six paintings, which were appraised by his colleagues Cornelis Liefrinck and Jan van Goyen and were by, among others, Pieter van Veen, Moses Uyttenbrouck, David Bailly, Jacob Pynas, Daniel Verdoes, and Jan Tengnagel, along with two portraits started by Paulus van Someren. Upon Claes Lourisz. van Egmont’s demise in 1639, fifty-one paintings were registered, of which only four were mentioned as painted by the deceased. Among the others were works by Coenraet (van Schilperoort), (Jacob) Swanenburgh, Molijn, De Momper, Govert Jansz., and Mayor van Tethrode, and copies after Frans Floris and Badius (Badens?). Also, van Egmont owned large quantities of prints after such masters as Lucas van Leiden, Goltzius, De Gheyn, Cornelis van Haerlem, van Mander, Bloemaert, Elsheimer, and Rubens, as well as by Italian artists such as Polidoro, Tempesta, Bassano, and Michelangelo. Even drawings are mentioned: by Jan Lievens and Goltzius, and one by Raphael. Abraham de Pape, a painter and follower of Gerrit Dou, contributed to his 1651 marriage 141 paintings, on top of his studio paraphernalia, along with ninety-four works, among which are various copies after Dou that De Pape painted himself. But the other forty-seven were attributed to such artists as Saftleven, Molijn, Ruysdael, Esaias van de Velde, Stooter, Jan van Goyen, the aforementioned Aernout Elsevier, Pieter Cornelisz. van Slingelandt, Adriaen van Ostade, the Flemish painters Pieter van Avont and Daniel Teniers, and a couple of masters who are virtually unknown today.

The year 1656 is also the date of the household inventory of Annetje Vechtersdr. Schuyrman, widow of Anthony van Griecken. From other Leiden inventories, it is clear that van Griecken also painted, though in the few deeds mentioning him—he belonged to a well-to-do Catholic family—he is not mentioned as a painter. The inventory estimates list fifty-four paintings, and a second list without estimates mentions seventy-three paintings. Among these are works by Jan Steen, Jan van Goyen, Jan Arentsz., Cornelis van Swieten, Esaias van de Velde, (Dirck?) Hals, Abraham de Verwer, and Brueghel, but also copies after Swanenburgh, Pynas, van de Velde, Bloemaert, and Goltzius, though we might wonder whether these originated from van Griecken’s studio. Vicar Eduard van Westerneyn was not an artist, but as the brother-in-law of Johannes van Staveren (died 1669), he probably owned the latter’s complete studio estate by 1674. Van Staveren was a member of the council and an oil miller; his activities as a painter were just a sideline. Westerneyn’s estate comprised seventy-three of his own works, but the rest of the 106 paintings in his collection were by other masters. Except for a Boerenkermis (peasant festivity) or maaltijd (meal) by Isaac van Ostade, the works in his inventory remain anonymous. The inventory of stained-glass artist Abraham van Toorenvliet was unknown until recently; this was drawn up upon his death in 1692.18 The list of 104 paintings was prepared by Abraham’s son, the painter Jacob van Toorenvliet, who had been his father’s pupil. Apart from his work as a stained-glass artist and writer, Abraham must also have worked as a painter. One of his own works in this collection, entitled Twee joden (Two Jews), is mentioned hanging in the hall. In addition, two paintings by Jacob van Toorenvliet and another piece by both father and son hung at the notary’s home. Of the other approximately one hundred paintings, Jacob van Toorenvliet ascribed some fifty-eight to about thirty masters and identified five copies after Rembrandt, Jan Steen, and Adriaen Brouwer, among others. There were three works by Adriaen van Ostade and one copy, and five original Jan Steen paintings, along with a copy. The painter with the greatest number of paintings (seven in all) was Ary de Vois.

As someone who was closely involved with painters’ activities, Willem Schwankert should also be mentioned. He brought in a great number of paintings when he married in 1694. Schwankert belonged to a family of ebony cabinetmakers and practiced the same profession himself. His shop also sold Nuremberg goods and fifty-three paintings, half of which can be connected with the names of those who painted them. In his case, we probably should consider these paintings to be items for sale rather than private property:19 as an ebony cabinetmaker, he also manufactured picture frames, as did those members of his family who called themselves picture-framers. Therefore, a connection with the art trade does not seem improbable.

All of this makes clear that, first, art ownership should for the most part be situated in the circles of town councilors and prosperous traders (mainly in the textile business), as well as in university circles and with dignitaries such as vicars, lawyers, doctors, and notaries. Second, many citizens from other walks of life also owned fairly large collections: craftsmen such as glassmakers, goldsmiths, plumbers, brick manufacturers, dyers, tanners, and, last but not least, brewers. In the case of several groups—innkeepers, the painters themselves, booksellers, and ebony cabinetmakers/picture framers—participation in the art trade may have been the reason for the presence of paintings on their premises.

Among the collectors, the high incidence of close family ties stands out, mainly in the latter years of the century. This is the case with cloth merchant Pieter van Hoogmade (1652 / sixty-nine paintings), Johanna van Hoogmade, widow of trader Jan Az. le Pla, at Breestraat (1687 / 151 paintings), and alderman Gerrit van Hoogmade (1683 / eighty-four paintings). More members of the le Pla family belonged to this group: Jacomina le Pla, widow of trader David van Royen (1682 / eighty-eight paintings), and the owners of Pieterskerkgracht 9, cloth merchant Abram le Pla and his wife Johanna Mabus (1677 / 99 paintings). Council member Isaac Gerard, who lived at Rapenburg 24 (1697), and whose collection of 264 works was the largest of all the inventories in the present selection, was the son of trader Michiel Gerard at Steenschuur (1670). The latter can also be counted among the most prolific collectors, with 118 works of art. Councilor Simon Vliethoorn at Rapenburg 10 (1690 / ninety-seven paintings) and tax receiver Frederick Vliethoorn (1691 / seventy-five paintings) were brothers.

Though the residents of Rapenburg were certainly a significant group in this study—of the five largest collections, four were to be found in Rapenburg dwellings!—they certainly were not the largest group. That last comprised residents of Breestraat, where, even more than on the Rapenburg, numerous traders had established themselves (in addition to the administrative elite). More than one-fifth of the selection—twenty-five estates—concerned homes in Breestraat. The third-most important street was Steenschuur, where another nine collections were concentrated. Yet six of the 120 household effects including artworks are to be found on Langebrug or Voldersgracht. Around the [Oude] Rijn also—Nieuwe Rijn, Vismarkt, Botermarkt—there was a concentration of nine households, and on Marendorp, on Haarlemmerstraat, and on Mare another thirteen can be counted. The rest of the owners lived scattered about the town: on Coepoortsgracht, Hogewoerd, Hooigracht, Hooglandse Kerkgracht, Maarsmansteeg, Middelweg, Noordeinde, Oude Singel, Papengracht, or one of the many alleys in between streets.

True Collecting

It would be useless to speculate about which of the Leiden inventories with proper art collections were the most interesting. Was owning paintings more a matter of decorating the home? At what point did it become a conscious collecting activity? Given our lack of knowledge regarding the way these collections were built, this question does not lead anywhere. Certainly in the seventeenth century, as we shall see, no rooms were favored as places in which to hang works of art. Paintings were found throughout the house, and their position in the house does not provide any indications about the nature of the room. Determining how many works of art per household inventory would be an utterly arbitrary exercise, even if the answer were obvious according to the highest numbers of paintings.

But we do find an indication of true collecting as opposed to household decorating in those cases where there is an indication of some form of patronage or a more personal relationship with one or more artists. The presence of a greater number of works by one artist might indicate this practice; in the seventeenth century, when people bought contemporary art practically exclusively, this was a recurring phenomenon. Of the selected inventories, 20% have five or more paintings by one painter, and in nine of those twenty collections, this was true for more than one artist. As might be expected, seven of those belong to the group of inventories comprising the largest numbers of paintings. Owning a large collection and having personal relationships with certain artists clearly went hand in hand.

The first Leiden resident in this group is Mayor Jan Jansz. Orlers (1640 / 142 paintings), who owned five or more paintings each by Leiden artists Coenraet van Schilperoort, Pieter Deneyn, David Bailly, and Jan Lievens, as well as three paintings by Lievens’s virtually unknown brother Dirck. Deneyn and van Schilperoort had died just before Orlers, in the 1630s. All four artists had been among the most popular painters in Leiden in the first half of the seventeenth century. Jean François Tortarolis (Rapenburg 24) (1656 / 173 paintings) also revealed himself to be a real art lover, with a personal preference for works by Leiden painters Coenraet van Schilperoort, Jan van Goyen, and Jan Porcellis. In addition, he probably owned eleven works by the Haarlem painter Dirck Hals and two more by “Hals” (probably Frans Hals). Hendrik Bugge van Ring (1667), who owned the second largest collection, with 237 paintings, is an even more striking example. He owned six paintings by Jan van Goyen, five by Jan Steen and Isaac van Swanenburgh (as well as one by the latter’s son, Jacob), and five by Cornelis Lelienbergh and Mozes Uyttenbrouck, who were active in The Hague. His closest relationship was with Leiden painter Quirijn van Brekelenkam, by whom he owned no fewer than eighteen works. Many of these must have been commissioned; among them were three portraits of the collector’s family. Brekelenkam is known mainly for his genre pieces, but as a Catholic, van Ring was likely to have been more intimately involved with the selection of such typically Catholic subjects as Saints Francis, Boniface and Clara, which Brekelenkam presumably painted for him on request.

Jan Jansz. van Rijn (1668 / 172 paintings) was also one of the six most prominent collectors, and he clearly favored Jan van Goyen (ten paintings) and Jacques Grief (alias Claeuw), one of van Goyen’s sons-in-law, a still life painter who is now virtually unknown. He owned thirteen works by Grief. He also owned many works by van Lelienberg, five paintings by Nicolaes Berchem (one of them a copy) and eight paintings by the Haarlem landscape painter Pieter de Molijn. Although the Leiden school was indisputably dominant, it is clear that François de le Boe Sylvius (1673 / 173) lived in Amsterdam before establishing himself in Leiden. This is the only possible explanation for his patronage of Experiens Sillemans and still-life painter Simon Luttichuys, by each of whom he owned six paintings. In Leiden, he was a patron of Gerrit Dou (ten paintings) and Frans van Mieris (seven paintings). He commissioned the latter to paint two portraits of himself and his wife. There was certainly a direct relationship between Sylvius and the artist; nevertheless, this does not justify the story noted by Houbraken that Sylvius asked the painter to present to him every new painting he made, for which he would then pay whatever others would offer.20 The medical doctor Gerard van Hoogeveen (1665 / 163 paintings) was primarily a client of Jan van Goyen, by whom he owned not only seven paintings but also four copies. He also owned works by Fabritius (probably Barent Frabritius), who lived in Leiden for a while. Of the nine Leiden collections consisting of more than 140 paintings, only in two cases do we come across a number of works by a single master significant enough to hint at a closer relationship with this artist: first, Gillis van Heussen (1661 / 190 paintings), though his inventory list hardly mentions any painters’ names; and second, Johanna van Hoogmade, widow of Jan le Pla (1688 / 190 paintings).

A number of smaller collections also point toward the possibility of a special relationship with an artist. Michiel Gerard (1670 / 118 paintings) owned five paintings by Pieter Deneyn. Abraham van Toorenvliet (1692 / 104 paintings) owned six by Jan Steen and seven by Ary de Vois. Gerson van de Kapelle (1675 / 103 paintings) owned five works by Pieter de Ringh. Innkeeper Aernout Eelbrecht (1684 / 94 paintings) owned five or six paintings by Leiden painters Cornelis Cruys, Cornelis van Swieten, and Dirck Verhart. His eleven paintings by Fabritius should probably have been attributed to Barent. In just one case, a specific connection between owner and artist was established. Helena van Swanenburgh (1657 / 87 paintings), widow of goldsmith Jan van Griecken, owned five paintings by her nephew Anthony van Griecken. It may also not be coincidental that the only four works by Isaac Jouderville, whose father was an innkeeper with a reasonable number of paintings on his premises, were owned by Julius Lefebre (1641 / 36 paintings), also an innkeeper.

From the above we may conclude that, insofar as patronage or at least personal relationships with artists existed, this concerned mainly painters working in Leiden (twenty-five out of thirty-six). The most cherished artist turns out to be Jan van Goyen, featured in all other analyses as the most popular painter in seventeenth-century Leiden. No less than six inventories feature five or more paintings by van Goyen. Other Leiden painters, such as Deneyn, van Schilperoort, Dou, Frans van Mieris, Steen, and Fabritius, achieve such a distinction in no more than two inventories. But Leiden painters Pierre Poreth, Isaac and Jacob van Swanenburgh and, later in the century, Dominicus van Tol and Carel de Moor, found some Leiden residents who were so fond of their work that they wanted to own five or more of their paintings.

Still, the most famous example of patronage in Leiden is, of course, the relationship between Gerrit Dou and Johan de Bije.21 Although de Bije was from a well-known Leiden family, surprisingly little about him is known; no occupation or function is mentioned anywhere. He must have remained unmarried, given the fact that a niece, Maria Knotter (Rapenburg 35), became his sole heir. One of the few official documents mentioning him is the contract he signed with painter Johannes Hannot to arrange a public exhibition on his premises of his privately owned twenty-seven paintings by Gerrit Dou. Visitors were asked to deposit a gift for the poor in a tin that was to be hung in the paintings room specifically for this purpose. De Bije even placed ads in De Oprechte Haerlemmer Courant to alert the public to the exhibition. Such a public relations campaign for a painter was highly unusual at the time. Moreover, Gerrit Dou, whose work was internationally appreciated, did not need the money. Selling was not De Bije’s intention either, as he probably kept the whole collection for himself. He probably owned paintings by other artists as well, but unfortunately no inventory of his collection has reached us. Many of the paintings featured in the list De Bije provided with the contract are present in important museums today and are counted among Dou’s top paintings.

The Role of Patronage in Collecting

In raising the question about the role that patronage played in collecting, the evidence has already hinted at certain collectors’ preferences for certain painters. The names of Coenraet van Schilperoort, Pieter Deneyn, and particularly Jan van Goyen provide examples. This preference can be recalibrated by taking the following research into account. Until 1640, names are mentioned only sporadically in inventories. Any knowledge of artists’ names must have been judged irrelevant at the time. From the 1640s on, we see a marked change: in the inventories we selected, a quarter of the paintings were associated with an artist’s name in the 1660s, when the art market flourished the most; it then increased to more than 40%, only to decrease to its former level after this decade. Still, only in some cases when a price estimate was required can we be certain that a particular painter was involved. The knowledge of the art market by both notaries and official appraisers was exceptionally good, as it was not restricted to just the well-known and popular masters. In the present survey, some 445 painters22 are featured, many of whom are relatively or even completely unknown today. We will not discuss all these names at this point. But it is interesting to learn which masters were most in demand by contrasting the first and the second half of the seventeenth century.

| Painters' names 1600-1649 | Number 1600-1649 | Number whole century | Number inventory | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schilperoort, Coenraet van | 26 | (35) | 10 | Leiden |

| Lievens, Jan | 14 | (35) | 5 | Leiden |

| Adriaensz., Jan | 10 | (13) | 4 | Leiden |

| Goyen, Jan van | 10 | (97) | 7 | Leiden |

| Swanenburg (together) | 10 | (31) | 5 | Leiden |

| Leyden, Aertgen van | 9 | (11) | 4 | Leiden |

| Deneyn, Pieter | 9 | (27) | 3 | Leiden |

| Velde, Esaias van de | 9 | (33) | 5 | Amsterdam / The Hague |

| Leyden, Lucas van | 7 | (9) | 3 | Leiden |

| Molijn, Pieter de | 7 | (52) | 6 | Haarlem |

| Bailly, David | 6 | (13) | 2 | Leiden |

| Stoter, Cornelis | 5 | (11) | 2 | Leiden |

| Bundel, Willem van den | 5 | (14) | 3 | Amsterdam/Delft |

| Elsevier, Aernout | 5 | (6) | 3 | Leiden |

| Painters' names 1650-1699 | Number 1650-1699 | Number whole century | Number inventory | Place |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goyen, Jan van | 87 | (97) | 27 | Leiden |

| Dou, Gerrit | 61 | (61) | 12 | Leiden |

| Molijn, Pieter de | 45 | (52) | 18 | Haarlem |

| Ostade, Adriaen van | 38 | (38) | 14 | Haarlem |

| Porcellis | 37 | (41) | 19 | Leiden |

| Molenaer, Jan Miense | 34 | (34) | 21 | Haarlem |

| Brekelenkam, Quirijn van | 32 | (32) | 11 | Leiden |

| Hals (unclear who) | 31 | (34) | total 22 | Haarlem |

| + Dirck Hals | 19 | (19) | (7) | Haarlem |

| + Frans Hals | 8 | (8) | (6) | Haarlem |

| Fabritius (Barent/Carel) | 28 | (28) | 6 | Leiden/Delft |

| Ostade, Isaac van | 28 | (28) | 12 | Haarlem |

| Steen, Jan | 27 | (27) | 12 | Leiden |

| Wouwerman, Philip | 26 | (26) | 12 | Haarlem |

| Staets, Hendrik | 24 | (24) | 14 | Leiden?/Haarlem? |

| Velde, Esaias van de | 24 | (33) | 12 | Amsterdam/The Hague |

| Brouwer, Adriaen | 23 | (24) | 8 | Haarlem |

| Verhart, Dirck | 22 | (22) | 9 | Leiden |

| Teniers, David | 22 | (22) | 8 | Antwerp |

| Lievens, Jan | 21 | (35) | 12 | Leiden |

| Mieris, Frans van | 21 | (21) | 6 | Leiden |

| Swanenburgh (together) | 21 | (31) | 7 | Leiden |

| Deneyn, Pieter | 18 | (27) | 10 | Leiden |

| Berchem, Nicolaes | 16 | (17) | 6 | Haarlem |

| Claeuw (De Grief), Jacques | 16 | (16) | 5 | Leiden |

| Heda | 16 | (16) | 9 | Haarlem |

| Arentsz., Jan (de Man) | 15 | (19) | 4 | Leiden |

| Swieten, Cornelis van | 15 | (15) | 8 | Leiden |

Coenraet van Schilperoort, mentioned most often (by far) in the first half of the century, was usually called Mr. Coenraet, or Mr. Coentje. Often his name is the only one mentioned in an inventory. This landscape artist has been largely forgotten by now. In the catalogue Geschildert tot Leiden anno 1626,23 just one painting and three drawings are attributed to him. He is mainly credited as one of Jan van Goyen’s teachers, although it seems van Goyen was his pupil for only three months. Van Schilperoort must also have collaborated with van Goyen, because Mayor Jan Orlers (1640) owned two landscapes by van Schilperoort to which Jan van Goyen added staffage. In his landscapes, certain themes were represented, and in this respect, too, van Schilperoort adhered to tradition. At Orlers’s home, for instance, a Strand met Petrus wandelend over het meer (Beach with St. Peter walking on water) and a Tocht van Hannibal over de Alpen (Hannibal’s journey over the Alps), as well as two Boerenkermissen (peasant festivities), are mentioned. Although van Schilperoort died in 1636, works by him were mentioned up to the 1660s. Despite his great fame earlier in the century, he does not figure anywhere later than that. His prestige must have plummeted by then.

Of the fourteen painters with five or more works listed in this period, at least nine were landscape painters like van Schilperoort. So it is all the more notable that Jan Lievens, number two on the list after van Schilperoort, is mentioned not only for genre pieces and portraits but also landscapes. Lievens is the only artist born after 1600 on this list and is thus the youngest by far. He remained popular in the second half of the century. Jan Adriaensz. was a generation older than van Schilperoort and died as early as 1619. Orlers mentioned him in 1640 as “een seer konstich ende geestich Lantschap Schilder, seer aerdich ende bevallich de vervallen ruijnen na te conterfeijten. Wiens wercken bij de Liefhebbers seer aengenaam ende begeert sijn” (a very able and intelligent landscape painter, who paints ruins very well. Whose works are liked and wanted by admirers).24 Still, we no longer encounter Adriaensz. in the inventories after the 1660s, as his work had probably become too old-fashioned. The catalogue Geschildert tot Leiden anno 1626 attributes two landscapes featuring ruins to him.25

Jan van Goyen was represented with the same number—ten paintings—but his popularity in Leiden was just starting and only really manifested itself in the second half of the century, although he had been based in The Hague since 1632. That was when he topped the list and left behind his contemporary Pieter Deneyn, who had been close on his heels during the first half of the century. The fact that Deneyn died as early as 1639 while van Goyen worked on until the 1650s must have had something to do with this. Unlike the masters mentioned up to this point, Esaias van de Velde, Pieter de Molijn, and Willem van de Bundel were not active in Leiden. Despite his early death in 1630, Esaias van de Velde also occupied a prominent position in the second half of the century, though not comparable with Molijn, who died in 1661; in the second half of the century in Leiden, Molijn occupied the third place after van Goyen and Gerrit Dou.

Few works by landscape painter Willem van de Bundel are known. Van de Bundel first lived in Amsterdam and later in Delft, yet even in the later period he was highly esteemed in Leiden. Witness the number of his works (nine) still featured in the sixty inventories.

Leiden-born painter Aernout Elsevier, last on the list of most commonly featured artists, apparently collaborated with Molijn. This is indicated in the inventory of brewer Simon van Swieten (1648), who was a brother-in-law to Elsevier, a painter himself, and an innkeeper; it includes a landscape attributed to Elsevier, with staffage by Molijn. Elsevier’s own inventory, drawn up on the occasion of the death of his wife, Maeycken Simonsdr. van Swieten (1626/28), reveals him to be the owner of eighteen landscape paintings. Attributions of any of his works are uncertain, however.26

Of the ten works belonging to the van Swaenenburgh family, the creator is not always clear. In the case of four landscapes, the painter was Claes Isaecsz.; three others were by his brother Jacob, along with, among others, a Toverij (scene of magic) and a Markt van Napels (marketplace at Naples). But it is not clear which family member was responsible for the Caritas Romana (Roman Charity) and a Fruitage (fruit still life). The portrait and still life painter David Bailly produced work that clearly belonged to another genre. Finally, it is remarkable (certainly in this half of the century) that a relatively high number of paintings by Aertgen van Leiden and Lucas van Leyden are mentioned in Leiden collections.

All in all, in the first half of the seventeenth century, the Leiden bourgeoisie bought its art on the Leiden art market: eleven out of the fourteen most popular masters were professionally active in Leiden. It is worth mentioning, too, that the ratio of native Leiden citizens to painters from elsewhere is not clear cut. That is due to the impossibility of tracing the background of the many painters who are unknown today.

Changes in Collecting

The second half of the seventeenth century shows a radically different picture. No longer do landscape artists dominate the list; their number is almost equaled by the number of figure or genre painters as well as by two still life specialists. This shift is typical of changes in choices of subject matter in this period. Nevertheless, landscape painting remained the most popular genre. The absolute dominance of works by Jan van Goyen was mentioned earlier. Except for Gerrit Dou (whose prominence is due to Maecenas Johan de Bye, who owned no fewer than twenty-seven of his paintings), Leiden collections contained twice as many paintings by van Goyen as by any other painter. Even four copies of his work are mentioned.27 Although several individual collectors owned greater numbers of van Goyen’s works, the distribution of his paintings throughout the inventories was also the widest by far. The case is quite different with Gerrit Dou. Not only were thirteen of the sixty-one works by Dou dismissed as copies; it is also clear that ownership of his works was much more exclusive. His paintings turn up in just twelve inventories, of which Johan de Bye’s deserves first mention. The second collector with a considerable number of Dou’s precious paintings was de le Boe Sylvius. After van Goyen and Dou, Porcellis and Quirijn van Brekelenkam topped the list of Leiden painters. Porcellis figures in a large number of inventories, while Brekelenkam gained his prominence thanks to the aforementioned patronage of Bugge van Ring. The popularity of Porcellis seascapes, specifically in the second half of the seventeenth century (there are fewer in the first half), is striking, as both father Johannes and son Julius had passed away before the middle of the century.

But what immediately jumps out in comparison to the previous period is that the focus on Leiden painters becomes much less noticeable. Works by Haarlem painters were acquired in great numbers, despite all the rules that had been issued since the 1640s, when the painters’ guild was founded and the authorities forbade the import of art from outside Leiden. Among the most popular painters are quite a few Haarlem names, beginning with Pieter de Molijn, who, like van Goyen, still belonged to the older generation. His works, too, were dispersed over the inventories; most collections included two or more works by him. The greatest number in one collection belonged to bookseller Jan Jansz. van Rijn (1668). Other notable Haarlem masters, such as Adriaen van Ostade, Jan Miense Molenaer, and Adriaen Brouwer, who had been working in Haarlem for a few years, were, unlike Molijn, typical staffage painters and belonged to a slightly younger generation. It is also striking how frequently the name Hals figures in the inventories, more often than not without a Christian name. Most are described as “companies” and “brothels,” but after the 1660s Dirck Hals—whose name is mentioned twice as often as his brother Frans—seems to have declined in the ranking and is hardly mentioned again.

Haarlem landscape painters of a younger generation who achieved a decent turnover on the Leiden market included Isaac van Ostade, Philips Wouwerman, and Nicolaes Berchem. It is unclear whether we should count marine painter Hendrick Staets among them; he is mentioned with no less than twenty-four paintings distributed over a great number of inventories. Staets is not mentioned in any of the biographical lexicons, but a signed marine painting by him is owned by the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. Between 1626 and 1659 he figures just once in official documents in Leiden and Haarlem, though he did not become a guild member in either city. This means that his domicile remains uncertain. He cannot be traced to Leiden by means of a marriage or christening. Nevertheless, his popularity in Leiden does emerge from the inventory of the innkeeper De Grient (1656),28 which narrowly missed being included in the selection; the inventory notes eleven marine paintings by Staets.

The important presence of the Haarlem painters in Leiden is visible not only in the aforementioned list of the twenty-seven most frequently mentioned painters. If we extend this list to include all seventy-seven painters by whom six or more works appear in the 120 selected inventories, it turns out that thirty-five painters worked in Leiden permanently or temporarily; twenty-five worked in Haarlem; and only a small minority came from other backgrounds, such as Amsterdam, The Hague, Delft, and, in one case, Utrecht. Among the painters most frequently mentioned was Esaias van de Velde, who had also been popular in the earlier period and whose popularity remained constant, even though he passed away in 1630. Also, by way of an exception to the rule, David Teniers provides evidence for the popularity of a painter from the Southern Netherlands (albeit the only one). His genre pieces reached the Leiden market in great numbers. He remained popular until quite late into the eighteenth century.

Mention of Fabritius, almost always without a Christian name, mainly designated Barend Fabritius, active in Leiden between 1655 and 1659, although his work was not widely distributed. Medical doctor Gerard van Hogeveen (1665) and innkeeper Aernout Eelbrecht (1684) were responsible for the considerable number of works by him, with ten and eleven paintings respectively. This means that Fabritius’s work was present in greater numbers than Jan Lievens’s, although the latter had been the second-most frequently mentioned painter in the first half of the century. He now figures much lower on the list, with twenty-one paintings. His studio companion from his earliest beginnings, Rembrandt, does not even figure on the list at all. Only thirteen works by Rembrandt (fourteen for the whole of the century) appear in the sample selection, including one copy.

Of the older guard of Leiden painters, the members of the Swanenburgh family and Pieter Deneyn still remain relatively popular. But we can now add Jan Arentsz. (de Man), often confused with the aforementioned Jan Adriaensz.29 Like Adriaensz., Jan Arentsz. painted landscapes according to the inventory descriptions; none can be located today. Hendrik Cornelisz. Vroom followed, with fourteen paintings. From the younger generation, many landscapes by Cornelis van Swieten appear; he was active in the middle of the seventeenth century. There are also works by Dirck Verhart, who only became a member of the Leiden guild in 1664, yet he is nevertheless represented with twenty-two works. This makes Dirck Verhart another example of a master well known in his own time who is now virtually forgotten; recently one landscape has been attributed to him.30

Although it is of course striking that so many genre paintings were acquired in Haarlem by Leiden citizens, the typical Leiden genre painters Dou and Brekelenkam are represented in large numbers in Leiden collections, along with others. The sample selection features twenty-seven works by Jan Steen and twenty-one by Frans van Mieris. Other well-known Leiden genre painters remain far behind, such as Dominicus van Tol and Ary de Vois, both present with ten paintings, and Pieter van Slingelant with two.

Two still life painters had also become best-selling artists. One of them came from a Haarlem family, Heda, although it is unclear in most cases whether the artist in question is the father or the son. Also striking is the popularity of the still life painter Jacques de Grief, alias Claeuw, a son-in-law of Jan van Goyen who became a member of the Leiden guild in 1651 and by whom no less than sixteen paintings are mentioned. This is more than those by more famous Leiden still life painters, such as Abraham van Beyeren (twelve paintings), Pieter de Ringh (eleven paintings), and Jan Davidsz. de Heem (nine paintings).

Prices

Of course, the large number of paintings in Leiden art collections depended not only on the relative appreciation of the various artists, but also on their availability and accessibility. The scale of the sample selection makes it impossible to assess the differences in average prices between artists, as too few inventories mention prices. In the top years, the 1660s, not one price is mentioned. Prices are known to have ranged generally from a few guilders to twenty. Only in exceptional cases were paintings estimated to be worth more than that: sometimes, for instance, when a painting was exceptionally large, but increasingly often because the appreciation for certain artists elicited a higher price. It is therefore interesting to examine which painters commanded the highest estimates, though it should be noted that many major painters simply do not figure into this limited study. The survey below of the most expensive paintings is divided into three periods covering the century in order to make clear the changes in valuation and increasing prices.

There is a discrepancy between the list of painters mentioned most often and the list of those whose works were most expensive. In the first half of the century, for instance, neither Coenraet van Schilperoort, Jan Adriaensz., or Jan van Goyen is mentioned, but instead the landscape painter François van Knibbergen. Also commanding high prices are landscapes featuring mythological scenes by Moses Uyttenbrouck and the historical and religious scenes by the Pynas brothers. In the middle part of the century, besides the notable valuation of paintings by Pieter Aertsen, it is mainly the landscapist and animal-painter Paulus Potter who jumps out. Among the masters active in Leiden, Abraham van den Tempel’s works were estimated highly. The often-repeated opinion that Jan van Goyen’s paintings were relatively inexpensive compared to those of other painters (which would explain why he was so popular and prolific) turns out to be quite untrue. During the whole century, works by him also feature on the list of the most expensive paintings, and the prices for the rest of his works do not diverge from those by comparable painters either.

| Highest Prices until 1650 (higher than 20 guilders) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Knibbergen, François van | 1630 | 100 - 30 |

| Pynas (Jacob or Jan) | 1620 | 66 - 40 - 36 - 30 |

| Uyttenbrouck, Moses | 1610 | 60 - 36 |

| Potter, (Paulus?) | 1640 | 48 |

| Bailly, David | 1640 | 40 - 40 |

| Momper, de | 1630 | 40 |

| Daniels, H | 1640 | 30 |

| Lievens, Jan | 1640 | 30 - 24 - 24 |

| Claesz., Pieter | 1630 | 28 |

| Goyen, Jan van | 1630 | 26 |

| Aertsen, Pieter | 1640 | 25 (copy) |

| Schilperoort, Coenraet van | 1640 | 25 (together with Jan van Goyen) |

| Porcellis (Johannes or Julius) | 1640 | 24 - 24 |

| Swanenburgh, Jacob van | 1630 | 24 |

| Highest prices 1650-1679 (higher than 20 guilders)(missing 1660-69) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Aertsen, Pieter | 1650 | 195 - 59 |

| Potter, (Paulus?) | 1650 | 140 - 26.10 - 26.10 |

| Tempel, Abraham van de | 1650 | 80 |

| Slabbaert, Karel | 1650 | 60 |

| Hondecoeter, (Gillis of Gijsbert?) | 1670 | 36 |

| Goyen, Jan van | 1650 | 33 |

| Brueghel, Jan | 1650 | 30 |

| Grebber, de | 1650 | 30 |

| Saftleven, Cornelis | 1650 | 30 |

| Molijn, Pieter de | 1650 | 24 |

| Everdingen, Allart van | 1650 | 24 |

| Lagoor, Johan | 1650 | 24 |

| Highest prices 1680-1699 (higher than 30 guilders) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mieris, Frans van | 1690 | 750 - 660 - 500 - 100 - 80 |

| Dou, Gerrit | 1690 | 300 - 30 - 30 |

| Elft, van der (Verelst?) | 1690 | 250 |

| Asselijn, Jan | 1690 | 200 |

| Lairesse, Gerard | 1680 | 200 |

| Ostade, Adriaen van | 1690 | 200 (Adriaen?) - 100 - 70 - 60 - 60 |

| Dujardin, Karel | 1680 | 120 |

| Lingelbach, Johannes | 1690 | 120 - 35 |

| Wouwerman, Philips | 1690 | 120 - 100 - 100 - 50 - 30 |

| Lastman, Pieter | 1690 | 100 |

| Snijders, Frans | 1690 | 100 |

| Teniers, David | 1680/90 | 100 - 40 - 40 |

| Berchem, Nicolaes | 1690 | 70 - 60 |

| Tol, Dominicus van | 1690 | 70 |

| Venne, Adriaen van de | 1690 | 70 |

| Holbein, Hans | 1690 | 60 -31 |

| Saftleven, Cornelis | 1690 | 50 |

| Steen, Jan | 1680 | 50 - 48 |

| Vroom, (Hendrik or Cornelis) | 1690 | 50 - 30 |

| Deneyn, Pieter | 1690 | 45 |

| Porcellis, (Johannes or Julius) | 1690 | 45 - 36 |

| Fijt, Johannes | 1690 | 40 |

| Goyen, Johannes van | 1680 | 40 - 40 |

| Kalf, Willem | 1690 | 40 - 30 |

| Pijnacker, Adam | 1690 | 40 - 30 |

| Staveren, Johannes van | 1690 | 40 |

| Willeboirts Bosschaert, Thomas | 1680 | 40 - 40 |

| Hannot, Jan | 1680 | 36 |

| Ring, Pieter de | 1690 | 36 |

| Puurs, Jan | 1690 | 32 |

By the end of the seventeenth century, prices start to diverge strongly. In Isaack Gerard’s inventory (1679; Rapenburg 24), the largest known collection in seventeenth-century Leiden, the estimates for some of the painters shoot up, including Leiden genre painters Frans van Mieris and Gerrit Dou.31 This supports Houbraken’s description of Gerard as one of van Mieris’s patrons. The high estimates—750, 660, and 500 guilders—must certainly have reflected what Gerard himself had paid the painter. A couple of other Leiden genre painters, such as Dominicus van Tol and Johannes van Staveren, also figure on the list, albeit with significantly lower amounts. Whether “van der Elft,” mentioned as the author of a life-sized Vrouwelijk Naakt (female nude) should be identified as the painter Pieter Verelst is doubtful. That makes it impossible to verify why this particular painting was valued at such a high price. A valuation trend that reflects the artistic tastes of the eighteenth century, however, is the appreciation of such “Italianizing” artists as Jan Asselijn, Karel Dujardin, Johannes Lingelbach, Nicolaes Berchem, and Adam Pijnacker. Philips Wouwerman is another artist who was highly appreciated until late into the eighteenth century. A number of still life painters—such as Willem Kalf, Johannes Hannot, and Pieter de Ring, did not command such high prices, although their paintings were estimated to be worth more than the average price. Also striking, the works of a few early landscape and seascape painters, such as Hendrik Cornelisz. Vroom, Jan Porcellis, and Pieter Deneyn, were still highly marketable. Of the Flemish painters, not only David Teniers but also animal painters Frans Snyders and Jan Fyt should be mentioned as belonging within this range.

Subjects

Changing interest in certain subjects becomes clear from the preference for certain artists and the price levels of their paintings. This development deserves more attention. The scope of the selected material allows us to consider this as representative for Leiden. The 7,993 paintings in the inventories32 have been codified by subject or genre, starting from the descriptions in the inventories themselves, rather than according to one of the existing iconographic systems. Such systems are not always practical when the paintings themselves are not available for viewing and seventeenth-century written indications are all we have to go on (see Appendix I).33 Of the 7,793 paintings, 2,100 were lacking a subject indication. In some cases where the artist’s name is mentioned, this was sufficient to determine the subject. Keeping this in mind, we may start with 6,135 paintings with subject indications in 120 inventories.34 In the following chart, only totals are mentioned for the various categories. Within the scope of this study, it is impossible to go into all the details in the various categories. The intention here is to identify a few important developments that became apparent from the numbers.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, portraits (A01) comprised the majority of the paintings in the homes of the bourgeoisie (besides religious scenes). Of these, family portraits (A02) constituted about 20% of all paintings in the first two decades. This coincides with the overview outlined earlier that shows how the paintings mentioned in the selected inventories at first represent the customary home decoration items, rather than actual art collections. In absolute terms, the number of family portraits per inventory (three or four) hardly decreased, but their percentage within the total collection of paintings decreased considerably, from some 23% in the first decade of the century to 4–6% starting in the 1630s. The portraits of famous people (A03), though fewer in number, simultaneously decreased from a maximum of some 13% in the 1610s to 1–3% in the second half of the century. About a quarter (sixty-seven paintings) of these were portraits of members of the house of Orange. Clearly their popularity plummeted dramatically beginning in the 1660s. During the period from 1660 to 1689, only three portraits representing the Orange family are mentioned. Those numbers would recover only at the end of the century. Portraits of famous Protestant theologians and Protestant foreign royals were also popular; on the other hand, we only occasionally encounter prominent figures from the Catholic sphere. A recurring theme is the series of Roman Emperor paintings, for instance in the homes of a professor, a Regent of the Walloon church’s consistory and a bookseller, but also in an innkeeper’s collection!

The category of tronie (A04) (head studies) did not decrease in terms of percentage; they are counted as portraits here. The term tronie invites confusion: it is generally accepted that these were not portraits, but genre-like heads, though this is not certain. As the description of “een tronie zijnde een conterfeitsel” (a painting representing a portrait) by Lucas van Leiden in an inventory from 1645 indicates, the inventories frequently featured identified portraits described as tronies. Still, it is significant that the number of tronies increased during the same years in which genre painting took off. Portraits and tronies remained a major part of art property, though in the course of the century their share halved, from a maximum of 38% to 16–19%.

An even more dramatic fall in popularity concerns religious themes (B01–B10). In the first decade, these constituted more than half the named subjects, though given the relatively small overall numbers, this should not be taken at face value. Also in this period, many kasgens (cabinets) could still be found in peoples’ homes, often fitted with doors as a kind of home altar placed on a buffet or tresoor (treasure) chest, of which a number are specified as alabaster. In the inventory of Machtelt Paets van Santhoven (1602), the widow of Lenaert van Schouwen, Esq., eight such kasgens stood in various rooms.35 In the 1620s and 1630s, religious subjects still represented 30% of the total number of paintings. After that, this percentage decreased by about half, while after 1670 not much more than 5–7% of paintings had religious subjects. In absolute figures, too, the number of religious paintings had definitively halved. It is striking how the numbers for Leiden diverge from what Montias observed in Delft.36 Even taking into account the fact that Montias examined a shorter period—1610 to 1670—this discrepancy still remains. Where Montias counted 25% religious paintings for the whole period, the same years in the Leiden sample only reveal 15.8%.

Within this category, the share of Old Testament scenes was—with the exception of the 1630s and 1640s—slightly smaller than that of New Testament themes. The stories of Abraham, Jacob, Moses, Elijah, David, and Solomon continually turn up in the inventories, as do the stories of Lot (twenty-one times), Susannah, and Judith (both seventeen times). Among the New Testament subjects, Christus geboorte (Birth of Christ) and Drie Koningen (The Adoration of the Magi) were popular, but the Annunciatie (Annunciation) rarely appeared. After these, the largest contingents were scenes from the Passion and The Last Supper, but Christus en de Emmausgangers (Christ on the Road to Emmaus) (twenty times) was also one of the frequent subjects, along with Christus met de Samaritaanse vrouw bij de put (Christ and the Samaritan Woman by the Well)(fifteen times). Of the parables, Barmhartige Samaritaan (The Good Samaritan) (eighteen times) and the Verloren Zoon (Prodigal Son) (thirteen times) were particular favorites. Paintings of the apostles and the evangelists (B07) remained reasonably constant until sometime into the 1660s, but the percentage and number of representations of saints (B08)—a typically Catholic theme—declined quickly from the 1620s on.37 Scenes featuring hermits (B09) are found only starting in the 1650s, when Gerrit Dou popularized this theme—the examples are almost without exception by Dou or his followers. In the category of Christian allegories (B10), Caritas; the three theological virtues of Geloof, Hoop, en Liefde (Faith, Hope, and Love); and De Zeven Werken van Barmhartigheid (Seven Works of Mercy) are most frequently mentioned.

Representations of scenes from classical mythology and literature make up a percentage that, while varying from one decade to another, remains more or less equal overall (around 3%). Of the classical gods and goddesses (C02), Venus was the favorite, depicted either with or without Cupid (seventeen times), with Mars (five times) and Adonis (five times), and with Bacchus and possibly Ceres (eight times), while also being mentioned in the company of Juno and Athena (Paris Oordeel, or Judgment of Paris) (four times). The number of representations of Diana, with or without Actaeon (fifteen times) lags far behind, while Bacchus places third (twelve times). The other mythological scenes reveal a widely varied tableau, with hardly any figure standing out. In the category of Roman legends and history (C03), the story of Lucretia captured the imagination (eight times) as the secular equivalent of such virtuous and heroic Biblical women as Susannah and Judith. Themes from fiction from a later date (C04)—often called Poeterij—remained rare for the whole of the seventeenth century. Starting in the 1640s, we do see the themes of shepherds and shepherdesses (E01) turning up regularly. Whether the Naakte beelden (nudes) (F01) mentioned mainly from the 1660s also belong in the context of mythology and literature is unclear from the inventory description.38

Paintings of recent historic events (D01) are mentioned only occasionally and mostly concern episodes from the Eighty Years War, such as the liberation of Leiden, the Twelve Year Truce, the Dordrecht Synod, or sieges and naval battles. In just about every home, these themes also figured in engravings (most of them framed), hung mainly in entrance rooms and halls. The now almost forgotten battle scene Slag van Lekkerbeetje en Breauté (Battle of Lekkerbeetje en Breauté) (near Den Bosch in 1600) appears five times as a painting and three times as a print. It must have been the episode from the war against Spain that fired the imagination most. And this was the case not just in Leiden, as a great number of contemporary representations of this battle are known.39

Among the secular allegories (G01), the theme of the Vijf Zintuigen (Five Senses) (G02) is mentioned most frequently (thirteen times), often as a series of five small paintings or roundels, and it also appears in the inventories as a print series. Other well-known series such as the Vier Elementen (Four Elements), the Zeven Deugden (Seven Virtues), and the Zeven Vrije Kunsten (Seven Liberal Arts) were much less popular, and allegorical themes such as Tijd (Time), Ouderdom (Old Age), Fortuna, Vanitas (as a bubble blower or a naked woman), Peace, and Justice are not frequently mentioned as subjects for paintings either. Paintings featuring Love, on the other hand, are very popular (eighteen times). Among the rest of the allegories mentioned are various moralizing themes, such as Magere en Vette Keuken (The Fat and the Skinny Kitchen), Luilekkerland (Land of Cockaigne), Armoede en Weelde (Poverty and Wealth), the Strijd tegen de Dood (Fight against Death) and also the Strijd tegen de Deugd (Fight against Virtue), and—less commonly—De Schilderkunst Benijd (Painting Envied) or two scenes entitled Vinding en Misbruik van de Wijn (The Invention and Abuse of Wine) by Honthorst, owned by Hendrik Bugge van Ring. Should we suppose that the latter theme had any connection with the owner’s family, several generations of which had been innkeepers? At the Achterste Doelen Inn, a typical Protestant subject adorned a wall in 1653: Paus cramerij (Papist junk).

An important category comprised the so-called genre pieces, here defined as “figure pieces with social life/types.” In the first thirty years of the seventeenth century, such paintings are hardly ever mentioned. Only in the 1630s does the percentage double, and in the second half of the century it fluctuates between 15% and 19% of the total number of works. Within this category, peasant scenes (H03) form a sizeable but numerically quite stable group. The separately mentioned companies, brothels, taverns and so-called cortegaarden (civic guard pieces) (H04) are mentioned often, mainly around the middle of the century, after which time their number decreases somewhat. Starting at 1640 their percentage varied from 2–4% of the total number of paintings. At times, there were clearly pendants of peasant scenes, as in the case of the merchant Daniel Rogge, who in 1618 owned a Boerenbanket (peasants’ banquet) and a Herenbanket (gentlemens’ banquet), which hung next to each other in his voorhuis (entrance room) on the Breestraat. The main group of figure pieces (H02), though, encompasses widely diverging themes; it would hardly be feasible to present an analysis of these in the present context. Known subjects do appear on this list, such as an Oud man met geld vrijend (money-loving miser), a Borstetastertje (groper), a Keisnijer (quack doctor), a Vrouwtje dat een jongen luist (woman delousing a boy), a Wortelschrappertje (carrot cleaner), Gortentelder (oat counter) or Astronoom (astronomer), an Oestermaaltijd (oyster meal), a Drie-koningenavond (Epiphany) by Jan Steen, and a painting of the Valkenburgse Markt (Valkenburg market). The most frequent theme was people making music—either as a group or individually, singing or playing an instrument—but the many Toebackdrinckers (smokers) (twenty-nine times) demonstrate that this popular pastime became one of the most frequently pictured subjects in seventeenth-century painting, turning up in the sample much more often than, for instance, such well-known themes as Kaart- of Trictracspelers (card or trictrac players), Drinkende Mannen en Vrouwen (men and women drinking), or Doktersbezoek (doctor’s visit). The large number of Kaarslichtjes (candlelit scenes) and Nachtstukjes (night scenes) were for the most part by Dou and his followers.

Categorized separately are the so-called Spokerijtjes and Toverijtjes (scenes of witchcraft and magic) (H05), a designation in some inventories, mainly from the first half of the seventeenth century, of paintings by artists such as Jacob van Swanenburgh or Pieter Brueghel the Elder. In the sample, this subject turned up in no more than about ten examples.

A separate category was reserved for Batailles (battle scenes), so-called Roverijen (banditries), and Jachten (hunts) (J01). This group, which was more frequently mentioned from the 1640s on, henceforth made up 2–3% of the paintings in the selection. Specialists like Wouwerman and Palamedes and, above all, Leiden painter Jan Jacobsz. van der Stoffe were the principal purveyors, although some sixteen other (landscape) artists are mentioned in connection with these themes.

That brings us to landscape art—so typical for the Republic in the seventeenth century—the genre that outperformed all others starting from the 1630s. Looking at the numbers per decade, the spectacular advance of the landscape as a theme in painting becomes obvious: in the first decade, the theme hardly made up even 3%, doubling in the next decade to almost 6%. In the 1620s it rose to more than 8% and thereafter never dropped below 30%. From 1670 on, landscape paintings made up 40% of all cited themes. It should be taken into account that the people who drew up the inventories—usually not professionals from the world of painting—could, of course, easily recognize a landscape or seascape, and they might have been more inclined to use these descriptions rather than complex mythological or religious themes, which signals an expected measure of bias. But the increase is sufficiently spectacular to be self-explanatory.40 This makes landscapes (seascapes included) by far the single largest category, 30% of the total for the whole century. It is hardly surprising that landscape artists also topped the list of artists mentioned most often. Only some of the paintings were specified in more detail. It is notable that so-called Tempeeskens, or storm scenes, are mentioned mainly at the beginning of the century, sometimes and specifically in the case of seascapes, often as pendants: for instance, a Schoon weder (nice weather) and a Storm by Vroom, owned by the doctor Sandra in 1627, or a Stille Zee and a Stormende Zee (Quiet Sea and Stormy Sea) by Porcellis, owned by Jan Jansz. Orlers in 1640. Pendants often included a Winter and Zomer (summer) (K05). But more commonly, people owned single Winterlandschappen (wintry landscapes), mentioned sixty-one times, and just thirteen Zomertjes (summer scenes). The theme of Avondlandschappen and Nachtlandschappen (evening and night landscapes) (K06) occurs no more than twenty-five times, hardly more often than foreign landscapes (K08), which, except for a Turkish and a German landscape, predictably depicted Italian views. Frequently found, on the other hand, are seascapes featuring ships or beaches (K09). These occur for the most part at a somewhat later date than the usual landscapes, but starting from the 1640s they made up about a quarter of the landscape category.

A number of animal paintings that were not categorized as still lifes (L01)—those featuring cows or sheep, for instance—possibly depicted animals standing or reclining in a landscape. This is not always clear from the inventory entries. A large number of pieces representing horses or birds are only to be expected, and dogs (in hunting scenes) were a well-known theme. But the inventories also list various scenes featuring cats (five times), pigs (three times), rabbits (six times), hares (twice), and lions (nine times); a mouse and a lizard are also mentioned, and even a “dragon,” painted by Otto Marseuss van Schrieck, who specialized in representing reptiles, insects, and similar creatures. Other scenes featured exotic animals: parrots (four times), elephants, a monkey, and a tiger.