This essay revisits one of the most acclaimed paintings of Rembrandt van Rijn’s later years, Aristotle with the Bust of Homer (1654; The Metropolitan Museum of Art). The painter’s approach to the subject of this work owes much to visual precedents and to the reception of Aristotle among early modern men of letters, including within the intellectual circles of seventeenth-century Holland. The unusual appearance of the philosopher, which has often led to conflicting interpretations, becomes much clearer when considered against the long-standing perception of his cultural “otherness.” The stance and gesture of this Aristotle not only affirm his identity but point to key aspects of his epistemology, focusing on the role of touch as the first step toward knowledge.

This Alexander left his schoolmaster, living Aristotle, behind him, but took dead Homer with him. —Sir Philip Sidney, The Defense of Poetry (1595)

Rembrandt van Rijn’s striking image of a man resting his hand on a statue has long prompted conversations about its meaning. Its earliest mention is in the 1654 inventory of the collection of Sicilian art lover Antonio Ruffo, where it was identified as a figure of a philosopher, possibly Aristotle (384–322 BCE) or the thirteenth-century theologian Albertus Magnus (1200–1280) (fig. 1).1 This was the first of three paintings that Rembrandt (1606–1669) would eventually send to this collector, the other two being portraits of Homer, now at the Mauritshuis (fig. 2), and of Alexander the Great, which is believed to be no longer extant.2 The presence of all three of these works in Ruffo’s collection is known from another early inventory, whose compiler notes that the portrait of Aristotle or Albertus Magnus is the best of them.3

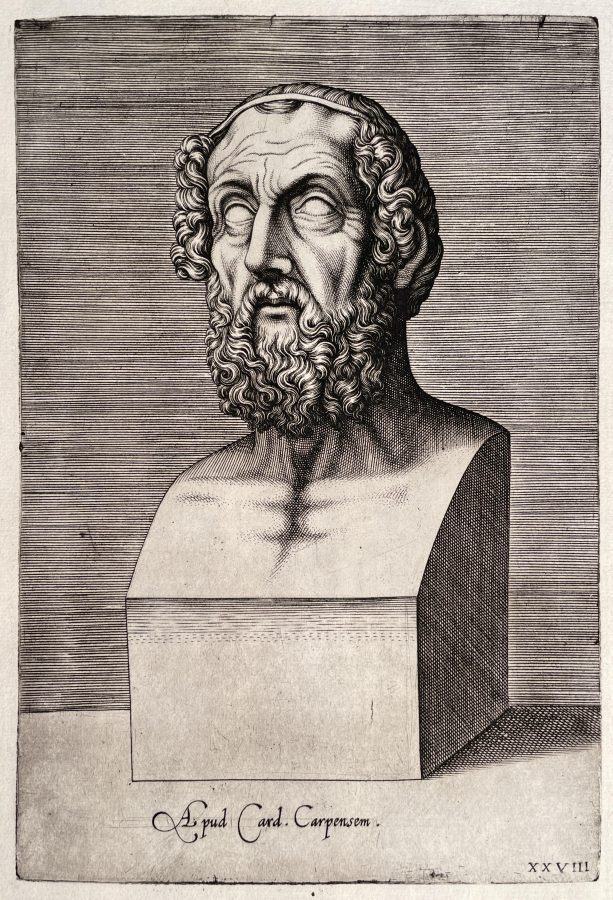

Although the dual designation of Rembrandt’s philosopher persists in other early records, he is also described with a variety of other terms, such as “savant,” “scholar,” “man of letters,” “physiognomist,” and even “poet.”4 The last appellation is almost certainly due to the bust he touches with his extended hand, easily recognizable as that of the blind Greek poet Homer (fig. 3). Following this line of interpretation, some scholars have gone so far as to suggest that Rembrandt may have conceived the standing figure as an imaginary portrait of Virgil, or perhaps some poet closer to his own time, such as Torquato Tasso or Pieter Cornelisz Hooft. Others, in turn, have gone beyond poets or philosophers altogether, arguing that this meditative figure—who wears a golden chain with a medallion imprinted with a face in profile, typically identified as that of Alexander the Great—is the favorite court painter of that ancient ruler, Apelles.5

This multiplicity of readings is all too familiar to students of Rembrandt, especially when it comes to works from the later part of his career. While the most famous examples of this indeterminacy may be the equestrian figure known as The Polish Rider (ca. 1655; Frick Collection) and the so-called Jewish Bride (ca. 1665–1669; Rijksmuseum), the artist’s tendency to play with the rules of art—whether in terms of iconographic codes associated with specific subjects or in his handling of the medium—has consistently led to diverse opinions concerning the subjects of his paintings, as well as spirited debates about his pictorial intent. The goal of this essay is to shed additional light on that intent in Aristotle with the Bust of Homer, as this painting is identified both within the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and in most of the scholarly literature. Rather than proposing yet another identity for the character at the center of this composition, I aim to clarify some aspects of Rembrandt’s portrayal of Aristotle by looking back at the visual tradition from which the artist drew and at the reception of the work of this philosopher in the early modern period—including within the intellectual circles of seventeenth-century Amsterdam.

Before proceeding any further, it is important to provide a brief review of the possible reasons for the dual designation of this character, described in the early inventory of Ruffo’s collection as either Aristotle or as Albertus Magnus.6 A number of commentators on this painting have found this conflation difficult to rationalize. Some have seen it as an indication of literary ignorance on the part of Ruffo and his familiars or possibly their indifference, as long as the composition could be accommodated to the popular genre of “philosopher portraits.”7 However, as Walter Liedtke and Susan Koslow have pointed out, a connection between Albertus and Aristotle would have appeared much more logical to those familiar with the Aristotelian tradition of the middle ages and the Renaissance than it does to modern scholars. After all, Albertus was widely considered the most important Christian commentator on this ancient philosopher.8 He tried to distinguish his attempt at a systematic analysis of the corpus of Aristotelian texts from commentaries by Arabic scholars that had been instrumental in Aristotle’s recent re-introduction to the West. This ambitious endeavor occupied Albertus for close to two decades, creating the foundation for what may best be described as a Christian reception of Aristotle.9 Indeed, Albertus’s emulation of this ancient thinker, as well as his own interest in natural philosophy and empirical method of inquiry, earned him the epithet of a “second Aristotle.” Albertus’s complete works were published in Lyon in 1651, merely a few years before Rembrandt sent his “philosopher” to Ruffo.10

Both Aristotle and Albertus were often included in Renaissance collections of portraits of uomini illustri (illustrious men). One notable example is the studiolo of Federico da Montefeltro in Urbino, where the portrait of Albertus is accompanied by a Latin inscription that underscores his connection to Aristotle via their shared interest in natural sciences (fig. 4).11 Although we cannot ascertain that Ruffo aimed to create a similar collection for himself, he did commission at least four additional portraits of philosophers from Italian painters.12 Furthermore, a record of his collection from 1650—that is, a few years before he acquired Rembrandt’s painting—mentions a portrait of Albertus Magnus.13 The presence of such a portrait may have, in fact, contributed to the subsequent conflation of Albertus and Aristotle, as well as to the description of the latter’s attire in another early inventory as “monk-like” (a guisa di monaco).14

Another early reference appears in a 1660 letter to Ruffo from the painter Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, better known as Guercino (1591–1666). Writing in response to the collector’s request for a painting that might complement the one sent by Rembrandt, Guercino notes that he would be honored to create a portrait of a “cosmographer” that could function as a pendant to Rembrandt’s “physiognomist.”15 While some have seen this description as confusing, or as further evidence of the difficulty that even Rembrandt’s contemporaries had in identifying this subject, Guercino’s words may well reflect the early modern reputation of Aristotle as the most influential classical authority on physiognomy.16 Furthermore, Guercino’s choice of a cosmographer as a type of knowledge seeker makes perfect sense within the context of early modern analogies between the study of human character (microcosm) and that of the larger world (macrocosm). Unfortunately, the painting Guercino writes about in this letter is not known at present. Its possible appearance can only be surmised on the basis of Guercino’s drawing of a cosmographer in the Princeton University Art Museum, as well as another painting on the same subject that he probably created about ten years earlier.17

Let us now consider the clues that Rembrandt leaves in this painting that suggest he was, in fact, portraying Aristotle. The most obvious one is the bust of Homer. As Julius Held and Walter Liedtke have noted, its presence may well reflect Aristotle’s esteem for the ancient poet, whose foundational works he references frequently in the Poetics.18 Rembrandt’s model in this case was a bust from his own collection, mentioned in the 1656 inventory of his possessions, along with busts of several other ancient luminaries, including Aristotle and Socrates.19 Interestingly, these three figures are the only ones in the inventory from the disciplines of philosophy and poetry; all others are of illustrious rulers.

The pose and stance of Rembrandt’s thinker are also important. His outstretched arm accords with many earlier images of Aristotle, including, most famously, his portrait next to Plato in Raphael’s Philosophy, popularly known as the School of Athens (fig. 5). Rembrandt was almost certainly familiar with that famous Vatican fresco through reproductive engravings and may have even owned an impression himself.20 Furthermore, this gesture’s association with the idea of touch as a mode of sensory knowledge was also recognized by early modern writers. Franciscus Junius the Younger (1599–1677), for instance, made this very point in his discussion of the characteristic marks of various philosophers:

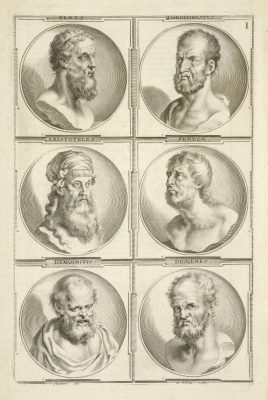

Apollodorus, Androbulus, Asclepiodorus, Alevas have painted Philosophers, and in their Pictures they took special care that every one of these Philosophers might be discerned by his proper marke: . . . Zeno with a wrinckled forehead, Epicurus with a smooth skinne, Diogenes with a hairie rough beard, Socrates with whitish bright haire, Aristotle with a stretched out arme . . .21

The gesture also calls to mind the comparable movement of Homer in Raphael’s Parnassus, who reaches his hand toward the figure of a scribe (fig. 6). Rembrandt’s familiarity with that visual source is evident from a drawing known as Homer Reciting Verses, which he contributed to the album amicorum of the Amsterdam connoisseur and art collector Jan Six (fig. 7).22 That drawing is dated to 1652, merely two years before this portrait of Aristotle. In other words, in conceiving his first painting for Ruffo as a metaphorical dialogue between philosophy and poetry, Rembrandt may have drawn inspiration from both of Raphael’s allegories of knowledge. And perhaps it was by looking at Aristotle from the School of Athens and Homer from Parnassus side by side that he came up with the notion of bringing them together to thematize the transmission of knowledge, so central to Raphael’s compositions themselves. Rembrandt’s portrait of Homer for the Sicilian collector was informed by the same idea. As has cogently been argued, before this painting was damaged by fire and cut down from its original format, it probably included two students taking notes, possibly alluding to the school founded by Homer on Chios.23 Within this context, one can see how Raphael’s image of the blind poet from Parnassus, who reaches his hand toward a scribe, would have provided an important prompt for this portrait as well.

And yet, while the face of Homer accords with the poet’s appearance as envisioned on antique busts, including possibly the one owned by Rembrandt himself, that of Aristotle is difficult to relate to any specific model. This figure is also markedly different from typical philosopher portraits from this period, like those by Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), which often give the impression of beggarly social misfits or outcasts.24 In contrast, Rembrandt presents us with a social insider comfortable with the powers that be, as indicated both by his rich attire and by the golden chain of distinction with a portrait medallion, generally identified as that of Aristotle’s most famous student, Alexander the Great (fig. 8).25

The luxury is consonant with Aristotle’s purported taste for ostentatious clothing and jewelry, especially rings, often noted by early biographers.26 These traits are also present in other early modern portraits of the philosopher, including the one from the studiolo of Federico da Montefeltro and a full-length portrait by Paolo Veronese (1528–1588) in the grand salon of the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice (fig. 9). In an echo of Raphael’s fresco from the Vatican, Veronese pairs Aristotle with Plato, adding the characteristic outstretched arm as the former’s identifying mark. At the same time, the long luxurious robe and turban-like headdress set this Venetian version of Aristotle apart from both his mentor and most of the other philosophers whose portraits decorate this ceremonial space.

Beyond Aristotle’s love of finery, the intimation of foreignness in some of his early modern representations has also been related to the role of Arabic commentators in preserving his writings and their reintroduction within the intellectual discourse of the west.27 One striking example of this relationship is Girolamo de Cremona’s (active ca. 1450–1485) illustration for the opening page of the 1483 Venetian edition of Aristotle’s Opera, which shows the philosopher conversing with a turbaned figure, possibly the great Andalusian philosopher Averroes (fig. 10).28 Although Aristotle himself is not wearing a turban, his tall headdress resembles that of the Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaeologus from a famous medal by Pisanello (ca. 1395–1455)—which became a stock figure for non-Christian or antique characters.29

A similar tendency to exoticize Aristotle marks many of his portraits in the medium of print. While most classical philosophers are typically represented bareheaded, he often wears headdresses that accord him a certain non-European or, one might say, Middle Eastern quality. Consider, for instance, the plate with six philosophers included in Joachim von Sandrart’s (1606–1688) Teutsche Academie, where he stands out from the others because of his turban-like head covering (fig. 11). In other engraved portraits from the period, we often find him wearing a soft cap that calls to mind the pilei associated with the ancient Phrygians, as well as other “barbaric” people that the Greeks came in contact or conflict with (figs. 12 and 13). The Phrygian cap was famously used to designate cultural “others,” notably in the depiction of the Macedonian infantrymen on the relief of the so-called Alexander sarcophagus (late 4th century BCE, Archaeological Museum, Istanbul).30

Given Aristotle’s strong association with Plato and the Athenian academy, one can easily overlook that he was, in fact, related to those “barbarians.” Born in the ancient Macedonian town of Stagira (Northern Greece) to a father who was both a medical doctor and a royal advisor, he went to Athens in 367 BCE to study at Plato’s academy. On the death of his mentor in 348, he was apparently forced to leave, possibly because of his Macedonian identity.31 Around this time, in 349/348, King Philip II of Macedon began his campaigns against the Greek settlements adjacent to his kingdom. Several years later, in 343/342, he asked Aristotle to tutor his son Alexander. During that period, the philosopher may also have taken part in political and diplomatic interactions between Athenians and Macedonians. In 335, merely a year after the young Alexander became the ruler of the Macedonian realm, he returned to Athens. This was also the year when word of Alexander’s conquest of Greek territories reached that city. Apparently, Aristotle’s persuasive skills convinced Alexander to spare Athens from destruction. As related in one Arabic source, the Athenians expressed their gratitude for his intercession by setting up an inscription in his honor, so that “that they would forever keep him in faithful and honored memory.”32 Nonetheless, they also continued to treat Aristotle as a foreigner, if not a political agent of the Macedonians. With Alexander’s sudden death in 323, the philosopher’s position became untenable. After numerous accusations, he decided to leave the lyceum he had established, dying in exile a year later, in 322 BCE.

Although one cannot assume that Rembrandt knew all of these details concerning Aristotle’s life, he was probably aware of his “otherness” of sorts. This leads us to a key question: where might Rembrandt draw inspiration for a portrait of Aristotle as someone who is both an insider and an outsider within his society? We have already noted that his representation of Aristotle accords with his tendency to depict characters from biblical narratives or ancient history in clothing that resembles contemporary representations of people associated with the Middle East. However, it also calls to mind something more specific: Rembrandt’s portrayals of figures associated with the Jewish culture and religion. Aristotle’s soft, wide beret, for instance, calls to mind the hats commonly worn by some members of the Jewish community of Amsterdam.33 These headdresses are often featured in Rembrandt’s works or those attributed to his workshop. Some of the most notable examples include the hat of the so-called Isaac from The Jewish Bride or the one in Portrait of an Old Man, possibly a Rabbi (ca. 1645) from The Leiden Collection (fig. 14).34 They are also common in his prints, such as the 1641 etching Christ Disputing with the Doctors, or the 1648 etching known in art historical literature as Jews in a Synagogue (fig. 15).35 The people included in this scene wear the kind of attire associated with German and Polish Jews. Mingling together in this space that alludes to a synagogue, both of these types would have appeared equally foreign to non-Jewish beholders.36

Rembrandt’s connections with the Jewish community of Amsterdam are commonplace in the literature.37 While there is no consensus concerning the extent of his knowledge of Jewish culture, he was readily exposed to it in his own Amsterdam neighborhood, as well as through possible discussions with some of the Jewish men of letters he counted among his acquaintances. Foremost among them was the Sephardi rabbi, scholar, diplomat, and book publisher Menasseh ben Israel.38 Within this context, there is one particular topos that may have particular relevance to Rembrandt’s portrayal of Aristotle: the philosopher’s apparent debt to the wisdom of the ancient Hebrews. This idea can be traced to several sources, including anecdotes from some of Aristotle’s students. According to Clearchus of Soli, writing around 300 BCE, at one point during his travels, Aristotle met and conversed with a Jew from Asia Minor, who impressed him both with his learning and his sober manner of life. This story was cited often by later writers, from Flavius Josephus, writing in the first century CE, to Menasseh ben Israel, who wrote that “Aristotle gained most of his learning from a Jew with whom he had much conversation.”39 Incidentally, Menasseh himself was compared to Aristotle by Joseph Bueno, the famous medical doctor and father of another of Rembrandt’s Jewish friends and patrons, Ephraim Bueno.40

A closely related legend concerns Aristotle’s alleged conversion to Judaism. In one variant of this narrative, Aristotle was born a Jew. In another, he obtained his knowledge about the religion through books he stole from the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem.41 Like the anecdote by Clearchus, this story circulated among Jewish scholars throughout the early modern period. One example is the treatise Las excelencias de los hebreos by the Marrano physician and philosopher Isaac Cardoso, published in Amsterdam in 1679, where one reads that Aristotle converted to “the Law of the Jews . . . at the end of his days.”42 This strand of Aristotelian lore was accepted by some non-Jewish scholars and used as evidence of the philosopher’s monotheism.43 In other words, Aristotle’s supposed Jewishness was seen as a redeeming value or an indication that, had he lived long enough, he might have become a Christian.

This perspective would have been especially appealing to those who were familiar with Menasseh ben Israel’s lifelong efforts to find a common language with Christian theologians, which earned him the title of “apostle to the gentiles.”44 In his exchanges with members of the Christian republic of letters, Ben Israel underscored that all of those who worship the God of Abraham belong to the same community.45 Within this framework, Aristotle, as an ancient philosopher who could “reconcile” Judaism and Christianity, might be equally acceptable to the adherents of both of these faiths.

Once again, one cannot assume that Rembrandt was acquainted with these more recondite aspects of Aristotle’s reception. But it is reasonable to hypothesize that, on receiving a commission from such an important collector as Ruffo, he may have sought some advice about the portrayal of this philosopher from his more erudite familiars, including Menasseh ben Israel, Ephraim Bueno, or Jan Six. Perhaps in the course of those discussions he learned more about the importance of the Arabic commentators for the transmission of Aristotle’s thought, about Aristotle’s “barbarian” (Macedonian) background, or even about his supposed conversion to Judaism.

Rembrandt’s pictorial license in portraying Aristotle calls to mind the words of Jan Six from the preface of his play Medea (1648) about his self-consciously novel treatment of the subject, which he announces will be as “free” as that of painters, who can depict any object as it suits them.46 While drawing on various images of Aristotle from the past, Rembrandt probably noticed some of their shared features—notably those orientalizing headdresses, such as the pileus-like cap or the turban. Although he uses similar headdresses for biblical characters, they are also common in early modern representations of Jewish people in general.47 One example is the title page of the 1708 study of Jewish antiquities by the philologist, Orientalist, and cartographer Adriaan Reland, Antiquitates sacrae veterum hebraeorum. It shows two Hebrew priests, one with a tall, soft cap comparable to those worn by Aristotle in some sixteenth- and seventeenth-century prints, and the other with a soft, wide-brimmed hat that is not all that different from the hat of Rembrandt’s philosopher (fig. 16). Although this publication postdates the painting by several decades, it is evidence that this characterization of ancient Hebrews was a well-established tradition.

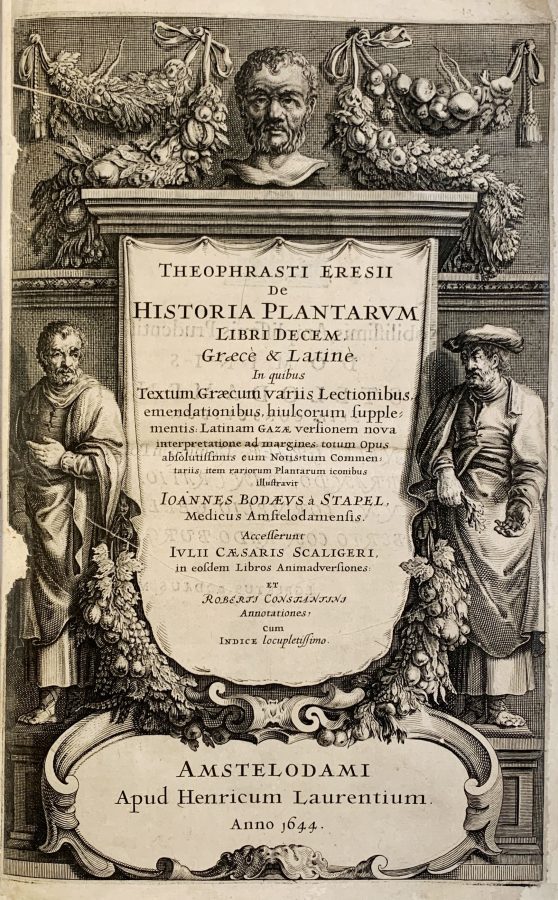

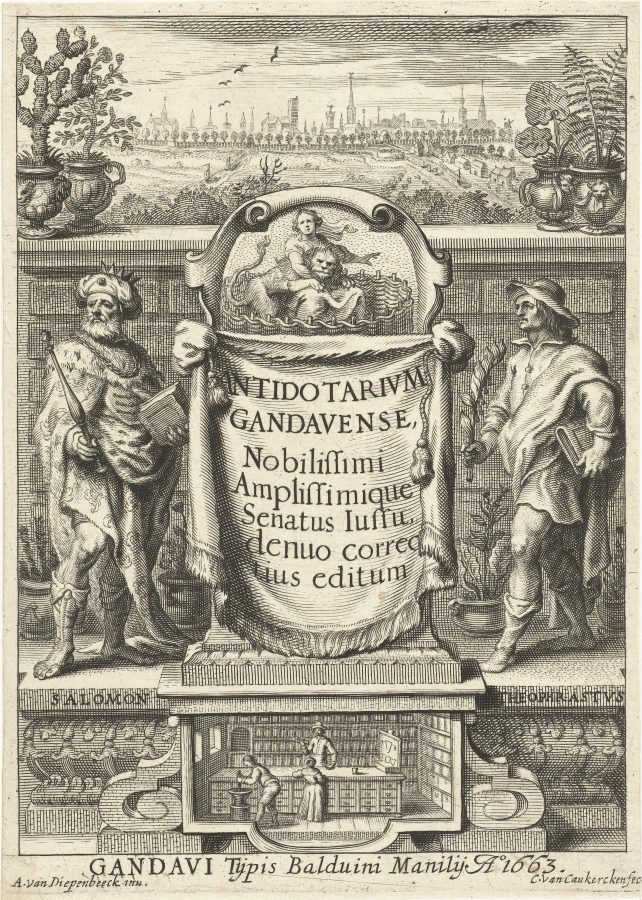

Another period image that may well have been among Rembrandt’s sources is the frontispiece to the 1644 Amsterdam edition of Historia Plantarum by Theophrastus (fig. 17).48 This peripatetic philosopher—and favorite student of Aristotle—was widely regarded at the time as one of the most important ancient authorities on botany. As noted earlier, Aristotle left Athens for good shortly after the death of Alexander. Before his departure, he bequeathed all of his writings to Theophrastus, making him the de facto successor at his lyceum.49 Like his mentor, Theophrastus reportedly praised the Jews for their natural gift for philosophy. His perceived debt to Jewish thought is also acknowledged in contemporary imagery, such as the frontispiece to the 1666 pharmacopeia Antidotarium Gandavense, which shows him in the company of the wisest of the ancient rulers, King Solomon of Jerusalem (fig. 18).50

In the Historia plantarum frontispiece, Theophrastus’s status as the father of botany is highlighted through his depiction as an outsized bust framed by luxuriant garland, which crowns the entire composition. He also appears along the left margin of the title page as a “living” person in a kind of conversation with Aristotle, who stands along the right side with the same outstretched arm and the wide-brimmed soft cap that we see in Rembrandt’s painting. As one contemplates them, especially vis-à-vis the large bust of Theophrastus between them, one can relate their attitudes toward one another to the silent exchange between Aristotle and Homer in Rembrandt’s painting, to the one between Homer and his students in the later portrait sent to Ruffo (see fig. 2), and even to the metaphorical conversation between Aristotle and his student Alexander, evoked through the faintly visible image-within-image on the golden medal that Rembrandt’s philosopher wears (see fig. 8). Similarly to Rembrandt’s composition, this image of Theophrastus from the Historia Plantarum also highlights the importance of touch. In the painting, Aristotle rests his hand on Homer’s bust; in the frontispiece, he grasps an uprooted plant in his hand. “Look here,” he seems to be saying to his student Theophrastus on the other side, “and touch—because this is how all knowledge begins.”

Within the traditional hierarchy of the senses, touch was invariably ranked fifth in terms of importance, after sight, hearing, smell, and taste. The most important classical source concerning this hierarchy was Aristotle’s treatise on the soul (De anima, ca. 350 BCE). At the same time, Aristotle underscored that without touch, which reached its highest form of development in humans, none of the other senses would be possible.51 This seeming contradiction was resolved by one of Aristotle’s Arabic commentators, Avicenna, when he suggested that while sight was the noblest of senses, touch deserved primacy from the standpoint of natural aptitude.52 The same perspective would be maintained by some of the most influential Christian Aristotelians, including Saint Thomas Aquinas, for whom touch was the root of all other senses and the foundation of our sensory abilities.53

Walter Liedtke has related Aristotle’s gesture toward the bust of Homer to the paragone between painting and sculpture, as well as the superiority of sight over touch.54 I propose a slightly different reading: that by placing the hand of this thinker on the head of the blind poet, Rembrandt may also be drawing our attention to the seemingly paradoxical status of touch as the most basic yet most essential of the senses. In other words, in this painting, Rembrandt is pointing to the interdependency of sight and touch. Furthermore, by foregrounding the tactile experience through the hand of the philosopher, he is also affirming a key aspect of Aristotle’s theory of knowledge.

In Aristotle’s treatise on the soul, there is an implicit rejection of the Platonic approach to thinking as a kind of seeing; what one finds instead is an analogy between thought and touch.55 As Aristotle observes, thinking results from grasping the form (eidos) of an entity, in much the same way in which our perception grasps the form of that entity in a material imprint.56 Since we grasp objects through their forms, thought is analogous to perception, and it begins from touch, the most fundamental of the senses:

Let us now summarize our results about soul and repeat that the soul is in a way all existing things; for existing things are either sensible or thinkable. . . . Knowledge and sensation are divided to correspond with the realities, potential knowledge and sensation answering to potentialities, actual knowledge and sensation to actualities. . . . It follows that the soul is analogous to the hand; for as the hand is a tool of tools, so thought is the form of forms and sense the form of sensible things.57

These ideas are reflected in the writings of Aristotle’s followers, including Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas. Indeed, Aquinas maintains that the finer one’s sense of touch, the better one’s ability to sense in general, and thus the better one’s intellectual capacity.58 Given this context, one can say that Rembrandt brings before our eyes a representation of a thinking person, though not just any thinker. Rather, he gives us his vision of the luxury-loving and not entirely Greek Aristotle, who is demonstrating the fundamental role of touch for thought.

Homer saw the world despite his blindness, using touch to sense the forms of things. Although he could not physically write his monumental works, his words as recorded by others (as Raphael reminds us in his Parnassus) became a foundation of western literature. The pile of books that Rembrandt places behind Homer’s bust may allude to that very legacy. Barely visible behind a curtain that has been slightly pulled to the side, the books hint that what we are seeing is just a portion of a much larger library yet to be unveiled or recovered. Quite possibly, this space into which we have been invited is intended to evoke Aristotle’s own library, given his reputation as a book lover, which earned him the nickname “reader” (anagnostes).59 And yet, these written records are almost lost in the penumbra of this imaginary studiolo. Their illegibility within the dark interior reminds us of the dialectic of sight and insight—but also of the way in which Aristotle’s reach for understanding through touch evokes Homer’s reliance on that sense as his way of seeing. At the same time, Aristotle’s outstretched arm makes us aware of the temporal distance between himself and Homer, a once-living person who is now present and remembered only through a tangible object—an artifact. Aristotle can know Homer by touching his representation (eidolon), just as we can know the philosopher—and the poet—through the work of art we behold.

This essay opened with a quote from The Defense of Poesy, in which Philip Sidney gives primacy to the art of poetry above philosophy as a mode of knowledge.60 One might say that Rembrandt makes an analogous claim in his composition concerning both poetry and painting. Although he foregrounds the figure of Aristotle, both the stance and the gesture of the praeclarus philosophus effectively turn our attention to the bust of the dead poet. In this way, Rembrandt makes us aware of the philosopher as a mediator between Homer and Alexander, just as Albertus Magnus mediated between Aristotle’s work and his Christian readers. Ultimately, Rembrandt reminds us of the power of works of art and their makers in mediating between these distant personages and ourselves—as he hints by placing his signature at the base of Homer’s bust, an artifact comparable to the one he has created for us, by which he hopes to be remembered (fig. 19).

Concerning the different appeals of poetry and painting, early modern art theorists like Franciscus Junius underscored that, for the maker of material artifacts—such as the bust of Homer or the painting we are looking at—the role of the imagination is secondary to the quality of “perspicuity” or “evidence.” The goal of perspicuity, as Junius explains by invoking Longinus and other important classical authorities who had addressed this topic, is to bring the distant personage or event before the beholder’s eye.61 This is precisely what Rembrandt seems to suggest through the hand of Aristotle, who by touching the bust of Homer affirms both the primacy of that sense for the acquisition of knowledge and the particular efficacy of material works of art in making the absent present.

When Philip II appointed Aristotle as mentor for his son, he expressly asked him to teach him about the world and its history through the poems of Homer.62 Aristotle did so in part by giving Alexander a manuscript of the Iliad, inscribed with his own notations—another kind of artifact. As Alexander marched eastward, keeping that annotated copy under his pillow, he lamented the fact that Homer was no longer alive to create poems that might do justice to his own military exploits.63 And yet, as the story goes, he also ordered that manuscript of the Iliad to be placed in a chest and preserved like the greatest of treasures.64

The Aristotle we see in Rembrandt’s painting is able to convey the spirit of Homer’s poems to Alexander by knowing them both in their written form and through the bust that he touches: a material artifact that brings the spirit of the poet before him. In a similar way, the painter brings the philosopher, the poet, and even the young prince before our eyes—through his own “touch”—as the first step in their pictorial coming-into-being.