Rembrandt van Rijn’s A Woman Bathing in a Stream (1654; The National Gallery, London) defies neat categorization. Although painted with loose, vigorous brushwork and prominently unfinished passages that suggest an informal study, the painting is signed and dated, indicating that it is a completed work. Its subject is similarly ambiguous, straddling a genre scene and a narrative representation. This article embraces these indeterminacies as purposeful and argues that Rembrandt’s play with early modern hierarchies of artistic classification extends to his experimentation with interrelated topoi central to Dutch artistic theory and practice. With this unprecedented image of a woman and her reflection, I argue, Rembrandt renders the metaphor of the mirror and mirroring as inadequate for his virtuosic art and challenges deeply gendered and poeticized tropes about artistic authority to assert his unique position within Dutch artistic culture.

Rembrandt van Rijn’s (1606–1669) intimate and exceptionally well preserved A Woman Bathing in a Stream from 1654 (fig. 1) depicts a young woman lifting her low-cut shift over her thighs and looking downward as she enters a reflective pool of water. Although painted with bold, fluid brushstrokes and unfinished passages characteristic of an informal study, the panel is nonetheless signed and dated at lower left, indicating that Rembrandt considered it a complete and autonomous work of art. Despite myriad attempts at identification, the painting’s subject is similarly ambiguous, straddling the border between a biblical or mythological narrative and a genre scene of a bather in nature, possibly Hendrickje Stoffels (1626–1663), Rembrandt’s common-law wife. This study embraces these indeterminacies as purposeful and argues that Rembrandt’s play with early modern hierarchies of artistic classification extends to his experimentation with interrelated topoi about truth and beauty in Dutch artistic theory and practice. Rembrandt’s unusual image of a woman and her reflection coincides with an emerging vogue for meticulously painted genre pictures of fashionable women at mirrors that showcase affinities between mirroring and picturing. Imaginatively naturalizing the picture type as nature’s own process of image production, Woman Bathing challenges the mirror paradigm with a vigorously painted, boldly naer het leven (from life) meditation on the interplay between illusion and desire. With this unprecedented and multivalent painting, Rembrandt rendered the mirror metaphor and mirroring as inadequate for his virtuosic art and also challenged deeply gendered, objectifying tropes about artistic creativity and authority to assert his unique position within Dutch artistic culture.

Purposeful Indeterminacy

Woman Bathing is unmatched in its vigorous, seemingly spontaneous brushwork and prominent areas of unfinish, even among Rembrandt’s loosely painted late works.1 While the painting shares affinities with some of Rembrandt’s other paintings, its novel combination of thick, dynamic brushwork and pronounced areas of incompletion has neither a clear painted precedent nor any direct successors. Woman Bathing is a unique and experimental work.

The woman’s head is relatively delicately painted, but parts of her body are obscured by the bold, thickly textured brushstrokes defining the shift and its folds. Her shaded left sleeve and arm are barely indicated by swift movements of the brush that leave bare the underpainting of brownish tone, and her left hand is not delineated at all. Flicks of the brush summarily indicate her right hand while a bold stroke merges her thumb with a fold of the chemise. So compromised by Rembrandt’s facture is this hand that a later, possibly eighteenth-century restorer gave it a more finished, rounded appearance, an addition removed when the picture was cleaned in 1946 (fig. 2).

Rembrandt confirmed the intentionality of Woman Bathing’s unfinished, informal appearance with his conspicuous signature and date. The picture’s comparatively small scale and panel, rather than canvas support—especially in contrast to Rembrandt’s majestic Bathsheba from the same year (fig. 3)—reinforce the impression of a free, informal study painted rapidly from life.2 Given the picture’s astonishingly loose, energetic brushwork, its closest parallel may be Rembrandt’s wash drawing A Young Woman Sleeping, also datable to the mid-1650s (fig. 4).3 One of Rembrandt’s few drawings executed with the brush alone, the sheet is a showpiece of his virtuosic drawing technique. Bold brushstrokes applied with great economy and precision seem almost miraculously to capture the sleeping woman’s form. Translating this vigorous, spontaneous aesthetic into paint in Woman Bathing, he achieved in oils a comparably vibrant interplay of wet and dry brushwork. Yet the picture’s effects of spontaneity belie its carefully planned design. Technical examination has shown that Woman Bathing was not executed alla prima but in a calculated series of stages. When Rembrandt applied a white brushstroke to indicate the woman’s right index finger, for instance, the monochrome underpainting must have been relatively dry.4

This mixing of techniques from different media to achieve vivid pictorial effects is characteristic of Rembrandt’s work.5 In certain paintings, his adoption of the graphic method of scratching, when combined with exposure of the underpainting or imprimatura, can even blur the distinction between preliminary sketch and final paint layer.6 An intentionally unfinished effect is also a hallmark of Rembrandt’s late style, as encapsulated in a statement that Arnold Houbraken attributes to Rembrandt: “A work is finished when the master has achieved his intention in it.”7 Woman Bathing, however, is unparalleled even in this respect.

The known provenance for Woman Bathing begins in 1739.8 Whether or not Rembrandt intended it for sale, presumably the painting would have appealed to contemporary liefhebbers, the rarefied audience of sophisticated collectors in the Dutch Republic.9 Their appreciation for non-finito artworks is recorded by Franciscus Junius, who wrote in 1637 that true connoisseurs saw in the unfinished works of great masters “the very thoughts of the Artificer.”10 Frans Hals’s (1580–1666) adoption of an increasingly loose, virtuosic technique in commissioned portraits, as Christopher Atkins cogently argues, likely catered to this class of Dutch patrons, whose discernment was reflected in the rough or rouw brushwork promoted by art theorists as the mark of a master.11 Compared to Hals’s loosely executed portraits, Woman Bathing is painted more thickly, boldly, and expressively, even to the point of disfiguration. Nonetheless, sophisticated liefhebbers like those who valued Hals’s trademark loose brushwork would also have been attracted to Woman Bathing. It has even been suggested that such a collector may have been less interested in the picture’s subject matter than in the bold novelty of Rembrandt’s signature handling.12

Just as the painting hovers between informal study and finished work, its subtly erotic subject of a solitary woman entering a pool of water, smiling gently as she lifts her shift, continues to elude definitive identification.13 Clear markers of recognizable biblical or historical narratives of a woman bathing in nature are conspicuously absent. There is no sign of the lecherous elders Rembrandt included in his renderings of Susanna and the elders (fig. 5) nor of the crucial letter that appears in his depictions of Bathsheba at her bath (see fig. 3), the two most popular subjects in Dutch art of women bathing outdoors and being spied on by lustful men. Still, the gold and red brocaded cloak discarded on the riverbank, variants of which are present in all of Rembrandt’s portrayals of these two Old Testament episodes, points suggestively to one of these biblical narratives rather than a generic bather in the outdoors.

Other identifications have been suggested, based in part on Christian Tümpel’s concept of Herauslösung, or the isolation of a figure from a recognizable biblical or classical narrative.14 Two interpretations, to which I will return, place the picture in the context of the Calvinist Church Council’s condemnation, in 1654, of the pregnant Stoffels for living like “a whore” (in hoererije) with Rembrandt. Jan Leja and Ernst van de Wetering argue that the painting depicts the mythological tale of the nymph Callisto before or after her rape by Jupiter, emphasizing that the woman is not nude but covered in a shift, as Callisto is traditionally shown and as she appears in Rembrandt’s Diana Bathing with Her Nymphs, with Actaeon and Callisto from 1634 (fig. 6).15 Other scholars read the image as an allegory of indecency, based on the resemblance of the woman’s pose to an ancient statue, known as the mulier impudica, or shameless woman, of a woman lifting her covering to expose her pudendum.16

While each proposal may be more or less plausible, I would argue that Rembrandt invokes familiar subjects while refusing to allow his painting to be categorized as any one of them. The painting’s tenuous connections with recognizable subjects are integral to its meaning.

Ambiguous subject matter characterizes Rembrandt’s work from the outset. Heroine from the Old Testament from 1632–1633 (fig. 7), which like Woman Bathing depicts a solitary woman suggestive of a familiar biblical figure, has likewise thwarted efforts to identify its narrative or pictorial source. The scene invokes without specifying several Old Testament stories of women—such as Esther, Judith, or possibly Bathsheba—preparing for encounters with or being spied on by powerful men.17 This tendency to blur pictorial categories indicates that Rembrandt did not embrace as a rigid set of rules the hierarchy of genres in early modern art theory, which designated historia (narrative history) as the most prestigious and honorable subject.18 Nonetheless, the hierarchy of genres, either explicitly or implicitly, was foundational to Rembrandt’s artistic enterprise broadly and to Woman Bathing specifically. His orientation as a history painter—demonstrated in the primacy he accorded to biblical, mythological, and historical scenes as well as his transformation of group portraits into showpieces of multi-figure narrative painting—governed his experimentation with artistic categories and norms. The period’s hierarchical aesthetic ordering also fundamentally shaped Rembrandt’s handling of different media. Not only are the subjects of his graphic work more comprehensive than those of the prestigious histories and lucrative portraits that dominate his production of paintings, but his prints and paintings of the same subjects can differ markedly from one another.

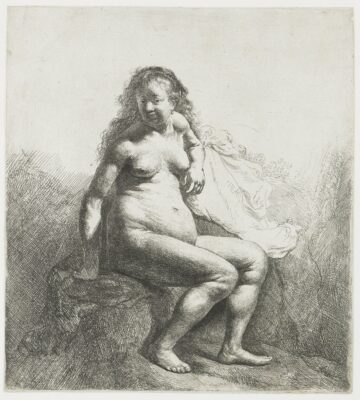

The graphic arts were generally less burdened with expectations of finish and clearly identifiable subject matter in the artistic theory and practice of the period. It is therefore not surprising that a precedent for Woman Bathing’s ambiguous ties to recognizable prototypes is one of Rembrandt’s prints: the etching Naked Woman Seated on a Mound from about 1631, an audaciously naturalistic remaking of the ideal classical nude (fig. 8).19 A discarded chemise, jewelry, and mantle serve as generic signals for the biblical themes of Susanna or Bathsheba, a bather or nymph in nature, or perhaps, as Amy Golahny suggests, a courtesan, based on parallels with Venetian images of courtesans and nudes in landscapes.20 According to Eric Jan Sluijter, Rembrandt incorporated these vague references to familiar pictorial scenes because “a print of just a female nude eyeing the viewer would have been too startlingly new.”21 Rembrandt seems to have revived this strategic ambiguity in Woman Bathing of 1654.

Woman Bathing straddles borders between informal study and finished painting, between genre scene and history subject; it is neither one nor the other but both simultaneously. This indeterminacy can be seen productively as an aporia, a blocked path or internal contradiction that leads to alternative, potentially richer interpretive insights.22 Woman Bathing anticipates the viewer’s desire to resolve the figure’s identity by considering a web of pictorial types, like Bathsheba, Susanna, or Callisto. And yet the picture impedes our impulse to categorize it as either a formal narrative history or a life study of a bather in nature. At the same time, multiple levels of irresolution draw attention to, while simultaneously interrupting, expectations of artistic categories, or iconographic and stylistic classification, ultimately evading a limiting determination of its potential meanings.

The unsettled narrative and vividly spontaneous brushwork of Woman Bathing create the impression that the painting has been suspended in the preliminary phases of transforming a life study into a more formal, finished work. Thus the image is in a state of permanent becoming.23 In this way, Rembrandt points to the foundational role of life studies in his project as a history painter who fashions lifelike images that bring the scriptural, mythic, or historical past into the present.

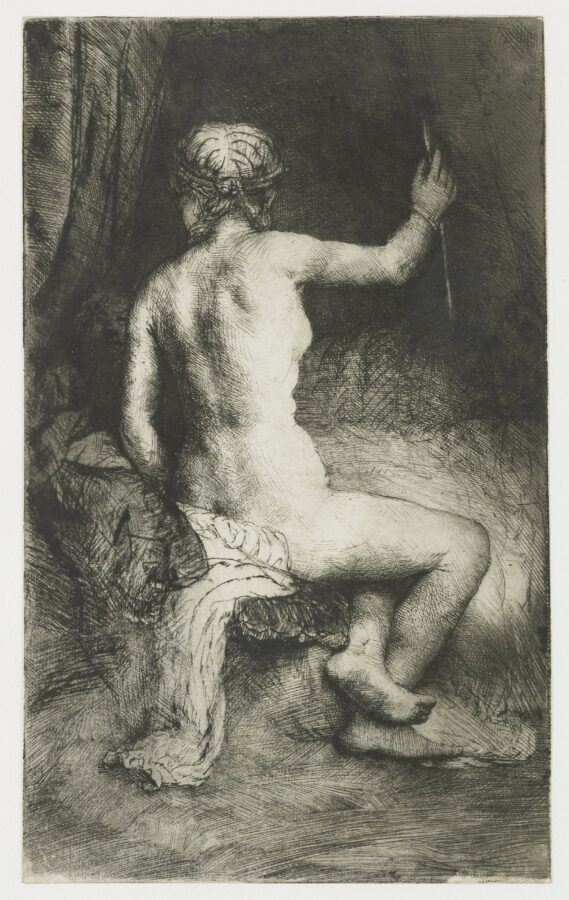

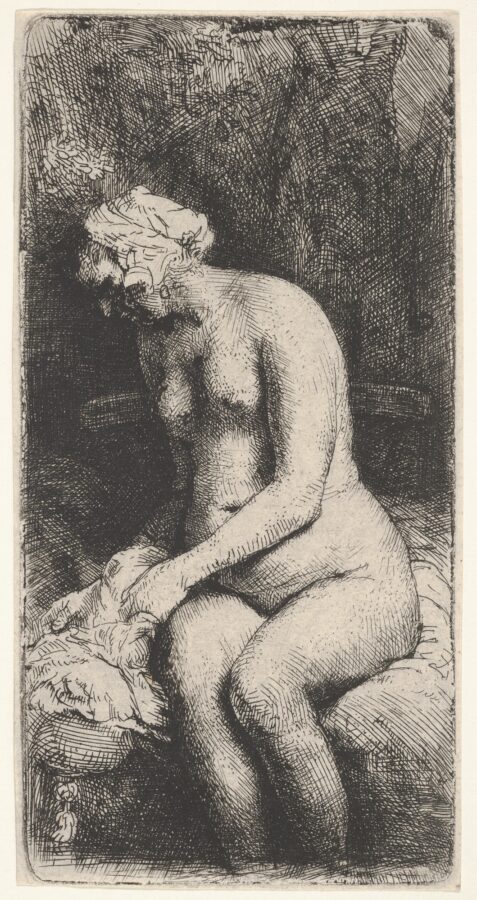

In the later 1650s and early 1660s Rembrandt continued to experiment with the borders between life studies and portrayals of traditional or historical subjects in several remarkable etchings of female nudes that draw attention to the work of modeling. In Woman with the Arrow, dated 1661 (fig. 9), Rembrandt seems to have converted the studio prop of a rope used by models to hold a pose into an arrow, suggestively transforming a life study into an image with historical or mythological resonance.24 Like the painted Woman Bathing, the etched Woman Bathing Her Feet at a Brook, dated 1658 (fig. 10),25 at once evokes and subverts a traditional scene of a bather in nature. Again the model seems casually posed, or to have been captured unposed. The fabrics and tasseled cushion beside her vacillate between signifiers of a history subject and bedding in the studio; vestiges of the chair or bench on which she sits remain conspicuously present. Rembrandt here intensifies the ambiguities introduced in the early Naked Woman Seated on a Mound (see fig. 8). Poised between image categories, these late, highly self-conscious renderings of the encounter between male artist and nude female model simultaneously acknowledge and transgress the different roles assigned to the graphic arts in hierarchies of artistic media and subject matter. Woman Bathing is a slightly earlier, painterly experiment that similarly reflects on and challenges early modern European aesthetic theory via the prototypical theme of woman as object of the desiring male gaze.

Mirroring Nature and the Poetics of the Mirror

In Woman Bathing, Rembrandt conjoined his experimentation with contemporary artistic conventions with an unprecedented image of a woman and her reflection. By assigning a prominent role to the reflective property of water, and by drawing out the affinities and differences between the reflective capacities of water and the mirror, Rembrandt effectively dramatized and naturalized two interconnected leitmotifs of seventeenth-century Dutch art and theory: the mirroring of nature as paradigmatic of painting and the pictorial subject of women and their reflections in mirrors. Woman Bathing coincided with Gerard ter Borch’s (1617–1681) reinvigoration, around 1650, of the mirror metaphor with meticulously painted, dazzlingly mimetic genre pictures of women and mirrors. These paintings showcase the affinities between mirroring and picturing with an image type associated with illusion and desire, which Ter Borch figured by mobilizing the Petrarchan trope of the elusive beloved. Drawing on the convention of the male poet’s unrequited desire for an inaccessible female beauty, this trope pervaded the contemporary discourse of art. Rembrandt’s vigorously painted Woman Bathing challenges Ter Borch’s equation of mirroring and picturing and proposes as an alternative to his artifice, a breathtaking naer het leven aesthetic. But like Ter Borch’s paintings, Rembrandt’s reimagined version of the woman-and-her-reflection type evokes Petrarchan poetics to highlight and comment on the relationship between illusion and desire in painting.

In no other work did Rembrandt devote such attention to rendering the glassy surface of water, painted thinly to capitalize on how the material properties of oil paint capture the water’s transparency. Touches of white paint brushed quickly onto the panel’s surface suggest the ripples created by the woman’s disruption of the water’s stillness. With her head tilted and a faint smile, she gazes down at this translucent surface, directing us toward the reflections of her exposed legs and the red lining of her robe on the riverbank. The resemblance to depictions of women at mirrors may not be immediately apparent, but his juxtaposition of the woman and her reflection aligns with the type’s pictorial structure, and the unguarded moment in her ablutions parallels scenes of women at their toilettes, transposed to a natural setting. Although the woman could be looking through the water, her downturned face guides us toward her reflection on its shimmering surface, evoking the idea that she sees herself.26 Her reflected legs would also be what the artist saw if painting the scene from life, reinforcing the picture’s claim to lifelikeness.

The mirroring surface of water as a paradigm of painting makes multiple appearances in early modern art theory. Alberti identifies Narcissus, who fell hopelessly in love with his own image reflected on water, as the mythical founder of painting. “What is painting,” Alberti asks rhetorically, “but the act of embracing by means of art the surface of the pool?”27 Karel van Mander’s Schilder-boeck (The painter’s book) of 1604 also refers to the mirroring effects of water in the discussion of reflexy-const (the art of depicting reflections).28 According to Van Mander, Jan van Eyck’s astonishing descriptive skills and the new medium of oil-based pigments transformed tafereelen (panels) into spieghels (mirrors) and thus converted painting into mirroring, nature’s own process of image production.29 Because, as he writes, “one sees [everything] perfectly inverted in clear-standing water,” it is the site where nature best represents herself.30 For Van Mander, the play of light reflecting on the smooth surface of water, as Walter Melion memorably puts it, “marks the threshold at which reflection becomes representation.”31 Rembrandt’s pupil Samuel van Hoogstraten poeticized nature’s production of its own image on the reflecting surface of water in his 1678 treatise Inleyding tot de Hooge Schoole der Schilderkonst: Anders de Zichtbaere Werelt (Introduction to the noble school of painting; otherwise the visible world):

Come, paint for me the reflection in the stream,

Of sky, clouds, city walls, and bridges, and trees,A mountain, and the lofty ramparts of castles;

Mirrored altogether upside down.The drinking cattle, fisherman, swan, and duck,

And rush and cattail, all appear inverted.32

This is similar to Van Hoogstraten’s oft-cited statement that “[a] perfect painting is like a mirror of nature; it makes things that are not there appear to exist and deceives in a permissible, pleasurable, and praiseworthy way.”33 Perhaps Van Hoogstraten heard Rembrandt talk about reflections on water in his workshop, which would be consistent with Van de Wetering’s contention that Rembrandt’s ideas serve as a bridge between Van Mander’s and Van Hoogstraten’s texts.34

Woman Bathing proposes a strikingly naer het leven, unconventional alternative to images of women and their mirror reflections. Popular in the Netherlands since the fifteenth century, the type was initially burdened with negative associations of female vanity and transience, as in the personification of Vanitas as a woman admiring herself in a convex mirror held by a devil in the Boschian Seven Deadly Sins and Four Last Things (Museo del Prado, Madrid). So deeply entrenched was this convention in Netherlandish painting that Dutch depictions of women with mirrors often seem inextricable from moralizing associations.35 Yet the mirror was also a symbol of purity, truth, wisdom, and self-knowledge, as well as a symbol for the sense of sight.

Rembrandt’s imaginative engagement with the subject of a woman and her reflection coincides with the type’s shift away from overt didacticism and toward greater refinement and a heightened self-reflexivity on the part of the artist. Gerard ter Borch’s so-called high-life genre paintings—which contemporaries identified as “modern”—were pivotal in this transformation.36 His earliest treatment is probably Woman at Her Dressing Table from around 1648–1649 (formerly Renand Collection, Paris), followed quickly by A Young Woman at Her Toilet with a Maid from about 1650–1651 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 11) and Woman at a Mirror from 1650–1652 in the Rijksmuseum (fig. 12). Ter Borch’s half-sister, Gesina, an artist in her own right, posed for all three paintings.37 His most sumptuous and finely painted version, Lady at Her Toilette in Detroit, dates from about 1660 (fig. 13). Genre painters such as Gerrit Dou (fig. 14), Frans van Mieris, Caspar Netscher, Gabriel Metsu, and Johannes Vermeer, among others, quickly followed suit with their own hyper-refined pictures of women at mirrors.38

Ter Boch’s innovative paintings are essentially burgerlijk reinterpretations of Venetian and Flemish mythological prototypes, exemplified by Titian’s (ca. 1488/90–1576) Venus with a Mirror (fig. 15), Peter Paul Rubens’s (1577–1640) adaptation of it (Liechtenstein, The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna),39 and the iconographic type known as the woman at her toilette.40 Ter Borch transformed the goddess of love into a fashionable, alluring young burgher woman in a private moment at her toilette, preparing for a suitor or social encounter. While Dutch moralists in the first half of the seventeenth century mocked female preoccupation with rarefied, aristocratic grooming routines, the toilette was widely adopted by the Dutch urban elite in the second half of the century.41 In contrast to the subject’s earlier censorious associations of women and vanity, Ter Borch’s toilette pictures suggest an appreciation for the women’s refinement and decorum, providing the viewer with privileged, gently voyeuristic access to this intimate feminine ritual. The Rijksmuseum’s Woman at a Mirror (see fig. 12) intensifies this effect of intimacy. The three-quarter-length, close-up, and cropped composition shows the woman from behind, her shoulders and neck exposed by the low-cut satin gown, turning toward a maid as a young boy holds a mirror that prominently reflects the side of her face.

Ter Borch’s burgerlijk variants of the toilette scene were integral to his larger project of reimagining the mirror paradigm with meticulously painted, elegant, modern genre pictures of stylish young women in shimmering satin, itself an epitome of reflexy-const. The Rijksmuseum and Detroit paintings in particular showcase the mimetic perfection of his art by juxtaposing the women with their reflections in a mirror. Ter Borch signals his ability both to capture and to surpass the mirror’s reflective properties by transforming the women’s transient reflections into a permanent presence. The affinity Ter Borch emphasizes between pictorial and specular images would have been informed by Renaissance precedents transmitted by works such as Hendrick Goltzius’s (1558–1617) Allegory of Visus and the Art of Painting (fig. 16).42 As Eric Jan Sluijter has shown, Goltzius here allegorizes the representation of consummate female beauty as the pinnacle of art.

Not surprisingly, given his richly textured impasto technique and concern for human affect over mimetic exactitude, Rembrandt treated the traditional toilette subject only once.43 A little panel in the Hermitage of a young woman securing or admiring a pearl earring as she looks in the mirror (fig. 17), which Rembrandt began around 1638 and returned to in the 1650s, is presumably the painting described in his 1656 bankruptcy inventory as a “Courtesan adorning herself.”44 Rembrandt’s pupil Gerrit Dou (1613–1675) quotes the picture in Woman at Her Toilette from 1667 (see fig. 14). In keeping with his aesthetic sensibilities, Dou turned the mirror around to evoke Rembrandt’s painting in the reflection of the woman seductively acknowledging the viewer’s presence.45

Rembrandt’s return in midcentury to Woman with a Mirror (apparently unsold from his early years) indicates his renewed interest in the theme of a woman and her reflection, imaginatively recast in Woman Bathing. Instead of a fashionable young woman epitomizing burgerlijk refinement, Rembrandt presents a young woman immersed in a quintessentially natural state of being, in a striking state of undress. Lifting her chemise over her thighs, and possibly revealing her pudendum, she directs our attention to her bare legs as they break the water’s stillness. As an image of a woman in nature looking toward the mirroring surface of water, Woman Bathing naturalizes the pictorial type of women at mirrors, vividly reinterpreting the scene as nature’s own process of image production.

Whether or not Rembrandt was responding directly to Ter Borch’s novel toilette paintings, the simultaneity of their explorations of the type reveals converging preoccupations.46 Despite fundamentally different styles, both Rembrandt and Ter Borch were drawn to the subject’s association with illusion and desire. Ter Borch’s hyper-refined yet compellingly lifelike fantasies depict graceful, reserved women who conform to the burgher elite’s social conventions.47 Rembrandt, by contrast, defies elite social norms with an uncompromisingly naer het leven scene of a woman covered only by a simple chemise, seemingly at one with nature. In juxtaposing the women with their transient reflections, or with a mirror, however, both call attention to the paradox of absent presence that defines figural representation. These seductively real women subtly invite the desiring gaze, while their reflections on water or in a mirror point suggestively to their illusory status. Rembrandt’s vigorous brushstrokes oppose Ter Borch’s equation of mirroring and picturing, yet the prominence he assigns to the woman’s reflection indicates a comparable absorption with the tension between illusion and desire embodied in the type.

Rembrandt’s and Ter Borch’s images correlate with the deeply gendered and eroticized discourse of painting of early modernity. Eric Jan Sluijter has highlighted the amorous and eroticized language that Dutch artist-writers use to describe the ideal relationship between the male painter, beholder, and painting. As Sluijter emphasizes, Van Mander’s Schilder-boeck and especially Philips Angel’s Lof der Schilderkonst (Praise of painting) from 1642 characterize the painter as a devoted lover of his work who seduces liefhebbers with dazzling illusionistic displays.48 In 1678 Van Hoogstraten also wrote that the most important quality for a painter is that “he not only appear to love the art but also truly loves depicting the niceties of graceful nature.”49 The greatest artworks were said to be inspired by the artist’s love for his model, as in the story of the ancient painter Apelles infatuated with the beautiful Campaspe, Alexander’s concubine, or later Raphael’s love for his Fornarina.50 The topos of the painter’s inspiration in love was also encapsulated in the Dutch motto “Liefde baart kunst” (Love gives birth to art), which distinguishes the artist’s creative work as a labor of love.51

This highly conventionalized and gendered discourse of painting was shaped by the Petrarchan poetic trope of frustrated desire for an elusive female beloved.52 The artist-poet Adriaen van de Venne’s (1589–1662) 1623 “Zeeusche Mey-claecht: Ofte Schyn-kycker” (Zeeland May lament: Or reflecting on my reflection) exemplifies how one contemporary conceptualized painting according to the Petrarchan conceit and how this trope mingled with mirroring and the mirror metaphor in Dutch artistic culture.53 Van de Venne opens with a melancholic author captivated by his reflection in a stream, illustrated with an engraved title print after his own design (fig. 18). A marginal notation identifies the speaker as Narcissus, the beautiful youth and mythical founder of painting who fell tragically in love with his own image reflected on water.54 Van de Venne then interweaves the Petrarchan trope of frustrated desire with a paean to painting, writing of painting’s power to comfort his “amorous pain” (van lieffelicke pijn) with a substitute for the beloved and proclaiming that painting is “a sweet art. . . . That creates out of nothing a beloved sweetheart. . . . The eyes desire, man longs / And I long all the more for this reason: because I see before me an image that has neither body nor speech / Nor movement or feeling, and is but a semblance . . . ”55 Van de Venne thus analogizes the representational act and its reception to the unfulfillable desire of Petrarchan convention.

Ter Borch’s paintings of fashionable young women, as Alison Kettering demonstrated in a groundbreaking study, draw on this Petrarchan formula of the elusive female beloved.56 Kettering showed that Ter Borch’s elegantly reserved women enact the inaccessible beloved of Petrarchism with averted or distracted gazes, or with their backs turned toward us. However, Ter Borch did not merely illustrate the poetic trope; he creatively adapted the conventions of the Petrarchan lyric to engage and reflect on the absent presence that underlies and animates the arts of both early modern painting and poetry. In this poetic tradition the woman’s elusiveness is a device that releases the author’s creative subjectivity. Her imagined presence but literal absence enables the descriptive praise of her physical and moral perfection.57

Like the Petrarchan poet’s evocation of a remote and unattainable beloved, Ter Borch’s art serves as substitute for unfulfillable desires. His stunningly lifelike women in refined toilette pictures (see figs. 11, 12, and 13), like their reflected images in the mirrors that act as metaphors for painting itself, remain forever beyond the reach of the desiring male viewer.58 At once a mirroring of the world and an act of poetic imagination, Ter Borch’s adaptation of the Petrarchan poetics of unrequited love constitutes a novel form of the virtuosic play between semblance and being that characterizes Dutch mimetic artifice.59

It is not coincidental that Ter Borch’s engagement with Petrarchan poetics seems to emerge first in toilette scenes.60 Modeling the viewer’s experience of the painting, the toilette scene was an ideal vehicle with which to launch his elevation of modern genre paintings by means of contemporary poetic and artistic paradigms. The toilette scene conflated the Petrarchan trope of elusive female beauty with the metaphor of the mirror, the dominant model of painting in Dutch art theoretical writings.

Rembrandt’s Woman Bathing is remote from Ter Borch’s engagement with the Petrarchan formula, drawn from longtime conventions. The woman’s vivid naturalness and frontality oppose the artifice of Ter Borch’s refined and aloof women, and her near-tangibility seems incompatible with absence and unfulfillable desires. Yet Rembrandt’s bold facture and the panel’s passages of exposed underpainting simultaneously evoke the woman’s proximity and distance, her resolution and irresolution, her presence and absence.61 In pairing the woman with her ephemeral reflection on water, Rembrandt points to this condition of absent presence central to representational art. Contemporary Dutch writings on art, as we have seen, underscore the Petrarchan trope of the male artist’s or viewer’s continually deferred desire for an elusive female beloved. The woman’s seeming defiance of this precept only confirms her role as a vehicle for Rembrandt’s beguilingly naer het leven, virtuosic performance.

A poem by Joost van den Vondel further illuminates Woman Bathing’s evocation of the Petrarchan structure of frustrated desire. Composed in response to a portrait by Govert Flinck (1615–1660), a pupil of Rembrandt, of the patron Jan Six’s wife Margarethe Tulp from about 1658 (Six Collection, Amsterdam), the poem—like Woman Bathing from a few years earlier—centers on a woman and her reflection. Like Van de Venne, Van den Vondel interweaves the Petrarchan trope of unrequited love with the myth of Narcissus, although with a revealing twist. He converts Tulp into Narcissus, writing that she “saw her likeness in her brook / Like a pearl in the clear water, living . . . ”62 So lifelike is the portrait that Six becomes “inflamed with love,” mistaking “the shadow for the being” of his wife. Six’s passion is thwarted when he realizes that the painting is merely a representation: “He kissed the image, and would have kissed it again. / But the painting itself had extinguished the flame.”

Both Van den Vondel and Rembrandt evoke and re-gender the myth of Narcissus’s enthrallment with his transient reflection on water with a woman looking at a reflecting pool in nature. This enlists the mythical founder of painting itself to signify the interplay between illusion and desire associated with paintings of women—in Van den Vondel’s case, at least, a portrait of an actual woman. In transforming Narcissus into a woman, Van den Vondel draws on the poetic subject of women at their toilettes,63 just as Rembrandt reimagines the iconographic conventions for women at mirrors, eroticizing the Narcissus tale in alignment with early modern gender norms. Van den Vondel’s casting of Six in the role of frustrated lover and Tulp as his elusive beloved frames the relationship between the portrait and its viewer as well as the analogy between painting and mirroring within the Petrarchan formula of unrequited love. While Rembrandt’s similarly Narcissus-like, boldly painted scene of a woman and her reflection defies the mirror paradigm’s fiction of transparency and suppression of materiality, the woman’s reflection on water points to her elusiveness, aligning the picture with the Petrarchan reading that Vondel applied to Flinck’s portrait of Tulp.

Rembrandt, like Van den Vondel, also vividly recasts the mirror metaphor of painting as nature’s own process of image making. In contrast to Van den Vondel’s imposition of the Petrarchan conceit onto Tulp’s portrait, however, Rembrandt challenges the trope’s conventionalism as well as the established codes and artifice of the pictorial subject of women and their reflections. Dispensing with refined and remote burgher femininity, Woman Bathing offers a tender image of unadorned femininity at one with nature. Rembrandt’s dynamic brushwork heightens the impression of immediacy, of witnessing the woman’s private pleasure in a mundane task. The brushstrokes also suggest Rembrandt’s lingering presence on the panel’s surface, positioning him as the scene’s original observer. Yet the woman’s reflection evokes her elusiveness, casting Rembrandt as the Petrarchan lover of his own work and transforming the labor of painting into a labor of love. Seen in this way, Woman Bathing remakes conventionally gendered and poeticized tropes about the paradoxes and compulsions of painting from nature.

Rembrandt and the Image of the Beloved

The likely identity of the woman in Woman Bathing is Hendrickje Stoffels, Rembrandt’s common-law wife, mother of his daughter, Cornelia, and eventual business partner.64 Although Rembrandt probably painted all three women who were his intimate partners—including Geertje Dircx (1610–1656), initially the nurse for his son, Titus—the only certain likeness we have is of his first wife, Saskia van Uylenburgh (1612–1642), whose features are known from a silverpoint drawing he made three days after their betrothal, on June 8, 1633 (Kupferstichtkabinett, Berlin).65 Despite the absence of a documented likeness of Stoffels, she has been plausibly identified as the model for the women in a number of works dating from the period of their cohabitation from the late 1640s until her death in 1663, including Woman Bathing. As is well known, Rubens and Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) promoted themselves and their art with paintings of their beloveds that rivaled Titian’s celebrated paintings of sensuous women. Rembrandt appears to have done the same with paintings and prints of Van Uylenburgh and Stoffels. All these works are embedded within a larger artistic and cultural discourse on the mythical origins of art, in which the female beloved embodies the male artist’s passionate devotion to the art of painting.

Documents from Rembrandt’s lifetime demonstrate that contemporaries recognized some of his artworks as portrayals of his wife and other intimates. In 1647, for instance, the merchant and probable art dealer Marten van den Broeck signed an agreement in which he offered, in exchange for ship equipment, a large number of paintings, both old and contemporary, including “a portrait of the wife of Rembrandt” and, remarkably, “the wet nurse (minnemoer) of Rembrandt,”66 presumably Dircx, who entered Rembrandt’s household as a dry nurse for the infant Titus in 1641 or 1642.67 In 1652 Rembrandt sold a portrait of his houisvrouw (housewife) to Jan Six, in all likelihood the painting of Van Uylenburgh from about 1633–1642 in Kassel (fig. 19).68 A 1648 inventory also lists “Two Effigies of the Artful Painter Rembrandt with his Wife.”69

Ernst van de Wetering notes that a number of Rembrandt’s sketches that originated in domestic situations depict a small, stocky woman with a “strikingly” round forehead and a broad face who reappears in several paintings: Portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels in a Fur Wrap from about 1654–1656 (fig. 20), Portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels in the Louvre from about 1654, Woman Bathing from 1654, Woman at a Half-Open Doorway from about 1656–1657 (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), Venus and Cupid (with Cornelia) from about 1657 (Musée du Louvre, Paris), and a portrait of Stoffels as an older woman dating from about 1660 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).70 While the women in these works generally resemble each other, they do not correspond exactly. But the paintings are not conventional portraits, and Rembrandt took similar liberties in his portrayals of Van Uylenbergh.

Rembrandt was certainly not unique in casting his wife or lover as the model for his art and was likely catering to an interest among liefhebbers to identify portraits of painter’s beloveds. Gabriel Metsu’s (1629–1667) wife, Isabella de Wolff (1629/30–1700), posed for more than a dozen of his paintings, while Frans van Mieris (1635–1681) used his wife, Cunera van der Cock (1630–1681), as a model in a quarter of his surviving works.71 In depicting themselves as husbands and lovers alongside their wives, Metsu, Van Mieris, and Rembrandt in effect domesticated the theme of love as inspiration for art.72 Yet Rembrandt’s depictions of Van Uylenburgh and Stoffels, informed by his self-conception as the preeminent Dutch history painter and his unconventionality relative to Dutch artistic and social norms, are distinctive. Rembrandt portrayed both of his wives in historicizing images embodying fecundity and female sensuality that emulate Titian’s canonical paintings of alluring women.73

Titian’s Flora from about 1517 (fig. 21), which was in Amsterdam between 1638 and 1641,74 inspired three paintings of Van Uylenburgh: in the year of their marriage (fig. 22), again in 1635 (National Gallery, London), and finally the year before her death (fig. 23). All three probably depict Van Uylenburgh as Flora, the Roman goddess of spring and fertility, although Stephanie Dickey argues that the final version portrays Van Uylenburgh as Glycera, the beloved of the ancient Greek painter Pausias and the purported inventor of flower wreaths.75 In the seventeenth century, Titian’s painting was thought to depict his beloved—a reproductive engraving from about 1640 identifies her as the woman whom Titian loved and who “tempts others’ hearts to sing.”76 Rembrandt’s quotation and adaptation of Titian’s prototype in paintings of his wife therefore signified his emulation of the Renaissance master and his engagement of the topos of the painter’s beloved as muse. Titian’s erotic Woman in a Fur Wrap (fig. 24) was also a direct or indirect source for Rembrandt’s painting of Stoffels clothed only in a revealing fur wrap and chemise, and adorned with gold chains, earrings, and a tiara (see fig. 20). Rubens had earlier adapted Titian’s half-length composition as the sumptuous, full-length Het Pelsken (The Little Fur), similarly posing his young second wife, Helena Fourment (1614–1673), nude and hugging a fur wrap, as his own Venus, the adored and adoring inspiration of his sensuous art (fig. 25).77 Van Dyck based a provocative image of his mistress Margaret Lemon (born ca. 1614), her nakedness covered only by a satin wrap (fig. 26), on Titian’s painting, which at the time was in Charles I’s collection.78

Like Rubens and Van Dyck, Rembrandt remade his illustrious predecessor’s women into more vividly naturalistic and particularized images of sensuality, and figures of creativity. Rembrandt’s paintings of Van Uylenburgh and Stoffels, like Titian’s, Rubens’s, and Van Dyck’s depictions of their beloveds, thereby evoke the intertwining ideals of the love of art and the love of a beautiful woman that were shaped by Petrarchan poetic tropes embedded in the early modern discourse of art.

Rembrandt’s pupil Ferdinand Bol (1616–1680) seems to have created an image of Rembrandt with his beloved by adapting Rembrandt’s sole depiction of the traditional subject of a woman at a mirror (see fig. 17). Bol’s monumental composition shows the same woman life size, admiring herself in a mirror, but now accompanied by a man holding a pearl necklace and looking directly out at the viewer (fig. 27). The couple, wearing fanciful dress and bedecked in gold and jewels, is traditionally identified as Rembrandt and Van Uylenburgh.79 While a general buyer may not have recognized Rembrandt’s features, an informed collector or liefhebber could have perceived the picture as Bol’s imaginative portrayal of Rembrandt alongside his own painting of a woman—perhaps Van Uylenburgh—which has now seemingly come to life. Bol appears to have enlisted the trope of the artist’s inspiration in the love of a beautiful woman to show his master as both creator and servant of beauty itself.

This context of historicized images of Van Uylenburgh and Stoffels sheds light on the suggestion that, in Woman Bathing, Rembrandt cast Stoffels as Callisto entering a pool of water to bathe after the discovery of her pregnancy and banishment from Diana’s troupe of nymphs (and that she thus alludes to the mulier impudica, or shameless woman).80 Van de Wetering proposes that moralizing glosses of the Ovidian myth by Van Mander and Gerard de Lairesse, who emphasize Callisto’s virtue and eventual redemption by becoming the constellation Ursa Major, suggest why Rembrandt may have depicted his pregnant mistress as Callisto in the very year she was condemned by the church council. He speculates that the painting was Rembrandt’s retaliation for her humiliation, a “wraecke des penseels” (revenge of the brush) in Van Hoogstraten’s words, and a gift to Stoffels comparable to Rubens’s gift of Het Pelsken to Helena Fourment (see fig. 25). The idea that the picture arose from Rembrandt’s reaction to Stoffels’s condemnation is conceivable; if so, his sympathetic image of her overcomes any retaliatory or negative tone. Rembrandt may also have been drawn to the motif of a woman lifting her skirt over her thighs in defiance of conventional ideas of propriety, adapting it for this tender image of his pregnant lover. Perhaps both Woman Bathing and Bathsheba from the same year (see fig. 3) are connected to Stoffels’s condemnation; although Van de Wetering rejects the identification of Stoffels as the model for Bathsheba, the correspondence between the date of the painting and the pregnant Stoffels’s summons seems too compelling to be coincidental.81 Yet the absence of identifying attributes of the Callisto myth (or any other recognizable scene) in Woman Bathing indicates that the picture was not meant to be linked definitively with a single narrative source.

Rembrandt may well have created Woman Bathing as an intimate, loving tribute to Stoffels. Regardless, the picture, like other portrayals of his wife and mistresses, should be understood within the broader cultural and specifically Petrarchan poetic framing of the artist’s beloved—the terms of which it expands on with the mirroring water, a reference to the dominant paradigm of painting in Dutch artistic culture.

Against the Mirror: Rouw versus Net

Rembrandt’s unusual Woman Bathing coincides, as we have seen, with Ter Borch’s modernization and elevation of genre painting with depictions of women at mirrors (figs. 11a, 12a, 13a). Unlike Ter Borch, however, Rembrandt, challenges the mirror as a paragon of ideal pictorial mimesis.

Despite invoking mirroring as a metaphor for painting in Woman Bathing, Rembrandt’s treatment of the reflecting water to which the woman directs our attention differs strikingly from the mirror reflections in Ter Borch’s pictures or in the genre paintings of his former student Gerrit Dou, whose work influenced Ter Borch and other genre specialists. Dou’s immaculate paintings epitomized the fijn or net (fine or smooth) technique that contemporary art theorists opposed to the rouw (rough) or los (loose) manner that Rembrandt practiced.82 In largely effacing the tracks of his meticulous brushwork, Dou achieved smooth surfaces that gleamed like a mirror, the model for perfect painting.83 Van Mander describes this technique as powerfully, even erotically seductive: “Praiseworthy netticheydt [meticulousness or fastidiousness], by giving sweet nourishment to the eyes, makes them tarry long . . . and when the image retains its appeal both from afar and close by; such things entangle [the viewer] and through his insatiable eyes, make his heart cleave fast with constant desire.”84

Just as a younger generation of genre painters embarked on their project to create ever finer, more wondrously mirror-like pictures and shift their production toward elegant, modern scenes of refined women and courtship, Rembrandt created an unprecedented, genre-like image of a woman and her reflection that proclaims his independence from and rivalry with their mode of painting. Rembrandt’s bold and fluid brushwork throughout Woman Bathing could not contrast more with the meticulous, smooth painting technique of this next generation of artists, whose works would soon form a new canon among liefhebbers willing to pay extremely high prices.85 Rembrandt vividly captures the reflective properties of the water’s surface, including the slight ripples created as the woman steps gingerly into the stream. The picture forcefully calls attention to his authorial traces, impeding the equivalence between mirroring and picturing claimed by the paradigm of the mirror as painting’s model. Parading his fluid, seemingly spontaneous brushwork in Woman Bathing, Rembrandt offers an alternative to the stylistic direction that Dou, Ter Borch, and other younger artists were in the process of consolidating with newly refined, modern genre pictures.86

Contemporaries associated the rough manner that Rembrandt adopted with Titian’s late style of painting, which was praised as a performance of consummate and effortless skill.87 Yet critical appraisals of rouw or los brushwork could be uneven. Van Mander had compared contemporary northern painters who embraced this Titianesque rough painting style unfavorably to the paragons of netticheydt.88 By 1678, when so-called fijnschilder paintings had become prized among liefhebbers, however, Van Hoogstraten takes the exact opposite position by indicting artists of his time who paint “each other blind with unnecessary finicking”—although he does praise Dou.89 Van Hoogstraten laments that their insignificant little pictures, citing specifically pictures of women, have seduced ill-informed collectors into paying exorbitant prices. “These nigglers,” he writes, “with those tidy little women with their tidy little panels . . . lure gold from the purse and have people believe that the only good paintings are those painted in their style.”90 He also takes to task these painters for their obsessive preoccupation with minutiae, complaining that some “are now so seduced by the desire for neatness that . . . they venture to depict almost imperceptible things.”91

Van Hoogstraten applauds above all the rough technique of thick, visible brushstrokes, advising painters to “lustily slather it [paint] on, paying little attention to a smooth blending-in.”92 He nonetheless does not name Rembrandt as the exemplar of this esteemed rough manner, praising instead the “loose brush” of Peter Lely (1618–1680). By the later seventeenth century, as is well known, Rembrandt’s unorthodox style of painting and uncompromising realism came into conflict with the idealizing, classicist canon of art advocated by younger artists and theoreticians, including Van Hoogstraten, his former pupil.93 Van Hoogstraten, who witnessed a dramatic shift in priorities of the art market between Rembrandt’s heyday and the time of writing his treatise, is representative of a generation of younger of artists who espoused a more ideologically prescriptive classicist orientation, and for whom Rembrandt, as the towering figure of an earlier time, was the primary target of their disapproval.94 Rembrandt’s anticipation of this shifting ground seems to be found in his exceptional and subtly polemical Woman Bathing of 1654.

In Woman Bathing, Rembrandt dramatizes the gendered, eroticized, and poeticized discourse of painting’s origins in desire and blurs the boundaries between genre, life study, and history painting in a critique of the mirror as a model of pictorial representation. Wielding his brush with a freedom that challenges the technical competence and artifice of his younger colleagues, Rembrandt parades the distinction between the “rough” and “neat” manners of painting identified in contemporary Dutch writings to assert his mastery over all pictorial modes, genres, media, and image types. In this aporetic and polysemic work, Rembrandt critiques his younger contemporaries’ increasing embrace of the mirror paradigm of painting while also declaring his identity as a universal artist who remakes artistic conventions from nature herself.95

Like Ter Borch and, later, Dou, Van Mieris, Metsu, Vermeer, and others, Rembrandt recognized and creatively embraced the metapictorial and poetic meanings encoded in the theme of a woman and her reflection. But the reflecting water toward which the woman directs us in Woman Bathing, like the mirror with which it correlates, refers to the surface of Rembrandt’s own picture, which he painted in such a way as to render the mirror metaphor of painting insufficient to his virtuosic art. Rembrandt’s characteristic rough handling rejects the reflective paradigm’s fiction of pure visuality, replacing its aura of detached observation with an insistence on the painter’s intervention in the world. Rembrandt thereby heightens our awareness of the permanent irresolution of the art/nature divide, intersecting with and reinforcing the picture’s irresolutions of artistic classification.96 The depicted woman was probably modeled on Hendrickje Stoffels, making Rembrandt’s engagement with the subject of a woman and her reflection yet more immediate, personal, and therefore resonant. In tenderly portraying his own beloved, Rembrandt links the labor of painting to the labor of love.