This essay reassesses a portrait of Anna of Denmark, Queen Consort to James VI and I, discussing its possible influence upon and use by her son, Charles, Prince of Wales, as an exemplary pattern of majesty. The portrait’s aesthetic references to Anna’s venerable genealogy and issue, alongside its singular originality, present the queen as a work of art wrought from the rarest dynastic materials and aesthetic precedents. It suggests that, in tandem with its function as a representation of the queen’s own majesty, the portrait acts within a semiprivate dynastic-familial context, as a mirror for the prince and as a connoisseurial model of martial majesty for his emulation.

This essay re-examines the emblematic portrait Anne of Denmark in Hunting Costume with her Dogs by Paul van Somer (fig. 1).1 The portrait of the queen consort of James VI and I, King of Great Britain and Ireland, was painted in the sitter’s early forties, when she was the mother of seven children, two of whom had survived into adulthood. Only one of those children remained in England: her son, Charles, then Prince of Wales, the future Charles I of England.

The portrait was paid for, and presumably commissioned, by Anna herself.2 During her lifetime, the portrait was displayed at Oatlands Palace, one of her residences. The portrait’s display within the context of Oatlands Palace has been the subject of recent articles by Jemma Field and Wendy Hitchmough. Both discuss not only the portrait’s iconography in relation to wider court politics but also its choreography at Oatlands in relation to other works of art in the palace’s evolving collections.3 A few days after Anna’s death, the work was sent to Prince Charles’s court at St. James Palace.4 Whether this move honored the wishes of the dying Queen or those of her son remains unknown. This essay considers the significance of the portrait’s posthumous presence at St. James Palace; the nature of its specific, intra-dynastic address to the new Prince of Wales; and his response to its stimulus within a semiprivate familial context of cultural transfer and dynastic succession.5

In what follows, I will demonstrate that the portrait exemplifies early modern elite self-fashioning as an act of creative originality, drawing on the same methods and principles as a highly trained artist creating a new work of art. Within the portrait, the stuff of Anna’s venerable genealogy is shaped and molded by the agency of her individuality. Anna’s portrait wittily presents her as an artwork of her own creation whose sitter has used her innate, God-given qualities—infused from on high, as her motto reminds us—to fashion the material inherited from her dynastic forebears. Practices of self-fashioning, based on erudition and creativity, allied to a virtuous genealogy, shadow the construction of this exemplary royal portrait, which, I will argue, quite literally impressed a future King. Anna’s aware complicity in this directed “impression” is signaled by her appropriation of the masculine pose of hand on hip and the commanding position she assumes on the hunting field.

Gender and Genealogy

The body of the consort as staged in her portraits—from betrothal portraits proclaiming her as a potential ornament to her marital court, to the effigies enacting royal funeral rites—always answered political imperatives. The image of the consort, shining with brilliants and garlanded with offspring, personified a pledge of prosperous continuity to the greater political body whose head was the wise ruler. While the primary duty of a royal consort was the reproduction in flesh and blood of the dual royal dynasties to which she belonged, the reiterative force of picturing these children in other media multiplied the visible might and majesty of her marital court. Portraits of consorts and the heirs, spares, and princesses they brought forth served important domestic and diplomatic purposes. As Catriona Murray has shown, royal children, when they arrived and even when they died, were replicated in portraits painted, printed, and cast.6 Anna’s portrait innovates from within this practice, functioning both as a screen for the external projection of the aura of dynastic majesty emitted by the reign of James VI and I and, more narrowly, as a mirror for her son, the future Charles I.

As such, Anne of Denmark both conforms to and departs from the conventions of the female consort portrait. It departs from these, first, in terms of its subject’s depiction while engaged in the courtly hunt. Anna wears green hunting garb, her physical stature raised by her high hat, embellished with a red feather trim. She is accompanied by a horse and a black groomsman wearing the Oldenburg family colors of red and gold. Her left hand grips the leash of a brace of two black-and-white greyhounds, while three wait unleashed at her feet. Her right hand is turned back and rests upon her hip, her elbow forming a jutting point. Anna is presented in the hunting landscape of Oatlands Palace. Its park wall features a gateway designed by the architect Inigo Jones, completed early in 1617. The specific, recognizable setting, unique among Anna’s portraits, shimmers under a sky dramatically split between darkness and daylight, as if to highlight the analogical relationship between the microcosm and the macrocosm, the earthly and the divine, so central to the period’s habits of thought.

An owl, the bird of Minerva, who, as goddess of wisdom and war, governed princely pedagogy, lurks flatly in the tree at the left. The groom, wearing the colors of the House of Oldenburg, creates a self-contained, satellite presence within the portrait; he looks at the Queen, modeling the serious regard expected of us as viewers. The bridled horse, richly caparisoned in red and gold, delicately raises one hoof and engages the spectator’s gaze. A deer runs alongside the palace wall. The dogs seem ready to set off into the bracken, and they wear collars emblazoned with Anna’s cipher. Anna’s motto, “La Mia Grandezza Dal Eccelso” (my greatness comes from on high) unfurls over the scene.

Anne of Denmark is often described as a splendid costume portrait. Yet this fails to recognize the painting’s singularity. The Queen does more than merely model her hunting garb. Her firm grasp of the dogs’ leash asserts her right to deploy the weapons of the field herself. Her jutting elbow signifies a status that is masculine and martial, and this forms the second departure from the normative conventions of consort imagery. If the female elbow akimbo is a signifier of a woman exceeding the limits of her gender, if she is figuratively elbowing those limits aside, then this is amplified in Anna’s portrait by her participation in the hunt, an activity performative of aristocratic masculinity via its use as training for war.7

It should be stated that there is ample evidence that women of the period, including members of the dynastic and political networks surrounding Anna, participated in the hunt.8 Anna’s brother, Christian IV, King of Denmark, wrote in his diary for September 13, 1607, that the cloak of his wife, Anna of Brandenburg, had been shot through while she was out hunting.9 In a 1605 missive to the Earl of Salisbury, the Earl of Shrewsbury gleefully reported: “My wife has sent you four pies of red deer . . . being of a stag that had the mishap to be killed by her own hand.”10 While hunting deer in July 1613, Anna of Denmark mistakenly shot James’s favourite hound, Jewel. As John Chamberlain related: “After he knew who did it, he was soon pacified, and with much kindness wished her not to be troubled with it, for he should love her never the worse; and the next day sent her a diamond worth £2000 as a legacy from his dead dog.”11 It is certainly the case that Anna kept greyhounds during 1617. In two letters dated March and April of that year, Thomas Watson wrote that two greyhounds he had seized for catching a hare had proven to be the Queen’s. His fears that he might be punished for this were unfounded, for the Queen sent to say if he found any more he should simply return them to her.12

It may be that arguments suggesting that women spectated, but did not (usually) participate actively in the hunt are overdetermined by surviving images of the hunt, most of which show male hunters. Yet intriguing portraits of royal female hunters also survive, as a recent exhibition at Schloss Ambras has demonstrated in relation to Maria of Portugal and Maria of Hungary.13 We might also include the possible portrayal of Elisabeth of Lorraine hunting in the monumental Months of the Year tapestry series (especially April, July, and November), woven by Hans van der Biest to designs by Peter Candid just a few years before Anna’s portrait was painted by van Somer (figs. 2, 3, 4).14 Further, Elizabeth I is represented as a huntress in woodcuts illustrating The Noble Arte of Venerie of 1575. This shows George Gascoigne, the translator of the work, presenting Queen Elizabeth with a knife to commence the undoing of the quarry, her privilege as the most senior figure attending a par force (“by strength of dogs”) hunt. Following the succession, Elizabeth’s image was replaced with one of James VI and I.15 No official portrait depicts Elizabeth in the act of hunting, although her iconography draws on that of Diana, the virgin Roman goddess of the hunt, and she is reported to have enjoyed the sport.16 The Devonshire Hunt tapestries, originating two centuries before Anna’s portrait, would have been known within the architectonic context of their contemporary display at Hardwicke Hall and consequently in relation to the identity of the Countess of Shrewsbury, “Bess of Hardwicke.” Her granddaughter, Arbella Stuart, was cousin to James VI and I and a close friend of Anna’s, performing in her masques.17 Peter Paul Rubens’s Wolf and Fox Hunt (ca. 1616)—a picture that the English ambassador to the Hague, Sir Dudley Carleton, attempted yet failed to buy in 1616–17—includes a composed female huntress, albeit at the periphery of the battle (fig. 5).18 Equipped female bodies actively participating in hunting appear frequently in representations of myths, such as in the Histories of Diana tapestry series, designed by Karel van Mander and woven by Francois Spiering in Delft, elements of which survive in English collections (figs. 6 and 7).19

Notwithstanding such a rich array of precedents, the hunting theme of van Somer’s portrait has been explained as a means of visually binding the image to existing portraits by Robert Peake the Elder of Anna’s deceased son and only surviving daughter: Henry Frederick (1594–1612), Prince of Wales, with Sir John Harington (1592–1614), in the Hunting Field of 1603 and Princess Elizabeth (1596–1662), aged Seven, also 1603 (figs. 8 and 9).20 The assumption that Anna’s portrait would have been received primarily in association with her children’s portraits conforms to the traditional historiographical expectations of consort imagery. Such expectations render the hunting landscape setting specific to these precedents and foreground Anna’s successful motherhood. The narrative continuity embedded in their hunting landscape settings (which, in the case of Peake’s pendants, is also an aesthetic-topographical continuity, connecting the portraits of brother and sister) may indeed speak to an intent to link Anna’s portrait with those of her issue, situating her identity within a chain of family resemblances. The continuity of English green complements the genealogical colors ordinarily constituted by the coat of arms, bodied forth in Anna’s portrait by the groom and her horse.

The children’s portraits appear to be set in the hunting park of the Harington family seat of Coombe Abbey, in Warwickshire. Sir John and Prince Henry were friends, and Elizabeth lived under the guardianship of Lord John Harington until her marriage to Frederick V, Elector Palatine, in 1613, shortly after Henry’s death (probably from typhoid), after which she departed to Heidelberg. Henry and Elizabeth perform idealized aspects of gendered participation in the courtly hunt. He is the martial nobleman, a leader among his peers, while her destiny is marital, as indicated by the couple seated in the bower in the background.21 Henry is shown sword in hand, at a critical moment in the process of the courtly hunt—the commencement of the ritual undoing, or flaying of the quarry; again, the privilege of the hunt’s most senior member. His commanding pose situates him as a worthy heir to the throne, ready to assume the leadership of his armies and the governance of his kingdom.

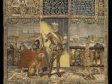

But Anna’s martial pose in Anne of Denmark cannot be straightforwardly situated within this binary gender patterning; her masculine excess points to the complexity of the portrait’s address. Anna’s pose is anticipated by those of her father and brother within their portraits woven into the series of genealogical tapestries known as the “king tapestries,” elements of which survive in the Danish National Museum, Kronborg Palace, and Stockholm’s Nationalmuseum.22 These were commissioned by Anna’s father, Frederik II, in late 1581 from the Flemish emigré Hans Knieper, whose workshop had recently been established in Copenhagen. When hung in the Great Hall of the Danish castle of Kronborg, they covered the entire wall surface, measuring 560 square meters. The completed series illustrated a one-thousand-year-old genealogical line, portraying one hundred Danish rulers—one of whom, Margaret I, was female—on forty tapestries, supplemented by three hunting scenes. Completed in 1585, the series concluded with the one hundredth ruler, the reigning King Frederik II, who was portrayed on the last tapestry with his son, the Crown Prince Christian, later Christian IV, brother to Anna of Denmark (fig. 10). Frederik’s great architectural projects—the castles of Kronborg, Frederiksborg, and Rosenborg—are arranged along the horizon, in defiance of their real topography, and court astronomer Tycho Brahe stands conversing in the background. The King wears armor, and his favorite hunting dog, Wilpret, waits by his feet. His reign represents martial success, scientific achievement, and cultural prowess.

Each tapestry includes a small panel containing a moralizing verse that describes the ruler and his or her reign, along with its successes and failures, comprising an encyclopedia of wise, foolish, and at times even tyrannical rulership.23 The rhyming verses are mnemonic devices, enabling viewers to remember their lessons, suggesting that the tapestries were intended to deliver a sustained impact upon viewers.

A little later, Frederik added a throne baldachin canopy and backcloth to the commission for himself and his queen. Taken as war booty, it now forms part of the collection of the Nationalmuseum of Sweden in Stockholm. Elizabeth Cleland has noted, “This was an inspirational moment of proto-Baroque theatre on the part of Frederick and his advisers: in a room encircled by . . . rulers represented in tapestry, the centrepiece would be the actual ruler himself, living, breathing, and framed against a tapestry surround.”24 This perceptive analysis highlights the way that this tapestry room functioned on multiple levels as historia, portraiture, and architecture, producing a heterotopic space presenting the reigning monarch as the culmination of the dynasty: genealogy perfected by ingenium (a person’s extraordinary, innate talent, often thought to be gifted to them by heaven).25 Frederik embodies the triumph of the individual will and intelligence over destiny—or perhaps, in this case, dynasty. His royal portrait is one of the first to present a king as a fully developed individual of his own creation, rather than a mere link in a dynastic sequence. Yet the king remains aware of his historicity within the chain of succession, as indicated by his inclusion of his young son and heir within his individual tapestry.

The king tapestries were famous throughout Europe, and no less so in England during Anna’s tenure as consort. Their expository, instructive tone, coupled with the themes of dynasty and the chain of succession, also inflects her portrait by van Somer. Emulating her father, Anna (as indicated by her motto) deploys her own self-fashioning—defined as the art of (re)creating oneself in the image of one’s best exemplars, using one’s God-given reason—to augment her venerable genealogy.26 Aesthetically too, her portrait and the tapestry series exhibit commonalities. Like her children, and like the standing figures in the Danish genealogy tapestries, Anna is shown inhabiting an identifiable, exterior topographical space: the hunting park of Oatlands Palace. Anna is standing upright, with the palace visible in the distance, a composition recalling those of the individual tapestries. Anna’s portrait refers to her Danish genealogy while anchoring it in a British context, while the Stuart succession is extended back through the Danish line.

Anna’s portrait also anticipates Anthony van Dyck’s portrait of Charles I of about 1635, now in the Louvre (fig. 11). This astonishing portrait shows the king, like Anna, standing beside his horse, accompanied by his groomsman. Charles rests his fist upon his hip, his elbow jutting toward the viewer, his turned stance mirroring that of his mother. Despite his assertive pose, the overall mood is rather contemplative. Charles presents himself, perhaps contrary to our expectations, somewhat more as a thinker than a martial leader. Walter Liedtke notes that it is surprising that van Somer’s Anne of Denmark and van Dyck’s Charles I have never been considered to be pendants, as their dimensions are almost exactly the same.27 In what follows, I will argue that these similarities are not accidental. These two works are kin in terms of both blood and art, and they actively articulate their subjects as mother and son, teacher and pupil, the model and its perfection.

Christopher Foley has observed that the development of the “dismounted equestrian portrait,” as materialized successively in the hunting portraits of Henry, Anne, and Charles, narrates the transference of increasingly sophisticated Netherlandish skills to a Stuart visual context, established by the English painter Peake at the commencement of the dynasty’s English reign.28 This is a seductive but ultimately flawed teleological narrative of aesthetic development, which passes over the purposeful agency of the political image in its early modern context. Anna’s portrait’s address to her son, and Charles’s portrait’s response to it, position them within a dialogic, intergenerational cultural transfer, transacting ideas of inheritance, individuality, historicity, artistic originality, and elite self-fashioning. Her pose highlights her indispensable role in preserving the body politic for the Stuart succession; her elbow anticipates the authority of her son as King. As indicated by the presence of Minerva’s bird, a symbol of wisdom, Anna may seek here to provide her son with a teachable model of masculine majesty to emulate. Charles’s active reception and digestion of this lesson, his use of it as an inspiration for his own self-fashioning as king, is made manifest in his own portrait by van Dyck. The courtly hunt provides the arena, both real and represented, in which these transactions were made. As in art, so in life: the courtly hunt was a practice long developed across Asia and Europe for the preparation of princes for their future roles as kings.

The Courtly Hunt as Princely Pedagogy

Hunting, especially par force hunting, was a privilege restricted to the nobility. The exclusion of other ranks was legitimated by framing hunting as military training. The courtly hunt’s ceremonial battles with the animal world were inherently representational: staged rehearsals for the military campaigns that noblemen were expected to lead as the warrior elite. To this extent, hunts were performances whose actors showed their readiness to defend their subjects. Hunts were also performative in that they constituted and perfected noble masculinity.

The courtly hunt played an important role in the education of princes, a role articulated within the interlocking framework of cynegetic and conduct literatures. The circulation of cynegetic manuals in manuscript, and later in print, which describe in detail the processes by which various animals should be hunted, was essential to the trans-aulic development of the ritualistic hunt across Western Europe.29 Late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century translations of key works into English, and modernized editions of older English works, often feature passages comparing the nuances of British practice with that of its medieval forebears, European neighbors, or antique exemplars.30

Cynegetic and conduct literatures describe the ideal behavior and attitude of the young nobleman toward his hunting practice and the nature of the courtly hunt’s performative effects on noble masculinity. This tradition begins with Xenophon’s ancient Cyropaedia. This Greek work originated the literary genre of princely pedagogy that became known as the “Mirror of Princes,” of which perhaps Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince (1532) and Baldassare Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier (1528) are the best-known examples. Within the Nordic region, the thirteenth-century Norwegian manuscript of the Konungs Skuggsjá, or King’s Mirror, forms the earliest example of this genre. Within this tradition, Anna’s dynastic portrait acts decisively as an exemplary mirror for her son.

This tradition continued in England with those writing under the reign of James VI and I; his extended address to his son Henry, Basilikon Doron (1599), constituted an exemplary pedagogical text that few seeking patronage could afford to ignore.31 However, I will focus here on Henry Peacham’s The Compleat Gentleman (1622) and James Cleland’s Hērō-paideia, or Institution of a Noble Young Man (1607), both of which draw on, cite, and respond to James’s text.32 Peacham’s career as a poet, emblem designer, and author is well documented; the lesser-known Cleland appears to have been a Scot, working as tutor to Sir John Harington, Prince Henry’s companion.33

James deals briefly with the courtly hunt in the third book of the Basilikon Doron, within a longer section on physical exercise. He advises his son that hunting with running hounds is the “moste honorable and noblest sorte” of hunting. Cleland and Peacham deal with the sport and its effects more fully. Both writers concur that hunting trains the mind as well as the body. As Cleland here describes it:

there is noe exercise so proper unto you as Hunting, with running hounds, wherby your bodie is disposed to endure patiently, heat, raine, wind, cold, hunger, and thirst; your minde made voide of al idle and naughtie cogitations, as it appeareth by the chast Diana. Hunting formeth the Judgment, and furnisheth a thousand inventions unto the Imagination: it maketh a man couragious and valiant, in his enterprises. . . . How am I able to reckon, the surprises, the strategems used for the obtaining of victorie, according to the beastes you doe hunt, which are all requisite & imploied without difference at the warrs, the hunting of men.34

The hunt prepares a man for far-reaching military leadership. Its physical rigors increase his tolerance of discomfort and strengthen his self-control; they demand concentration, judgment; and imagination. Hunting is not solely a trial of physical strength but of a man’s personal qualities. Henry Peacham writes:

Hunting, especially, which Xenophon commendeth to his Cyrus, calling it a gift of the Gods, bestowed first upon Chiron for his vprightnesse in doing Iustice, and by him taught vnto the old Heroes and Princes; by whose vertue and prowesse (as enabled by this exercise) their Countries were defended, their subjects and innocents preserved, Iustice maintained.35

Hunting prepares leaders for the public responsibilities of the defense of the realm from external enemies and maintaining the rule of law within it; such training includes a moral dimension. The pleasure afforded by the hunt is such that it requires great fortitude to pursue it with moderation. Cleland writes, “Morouer hunting is so pleasant, that if reason were not obaied, manie could not returne frõ such an exercise more then Mithridates who remained seauen yeares in the forrest.”36 Cleland warns against the nobleman’s surrender to the pleasures of hunting in the severest terms: “For if you neglect your necessarie affaies, you deserve to be punished with Lycaon, and Acteon, who were both hunted and killed by their owne dogges.”37

The specter of excess, of reason abandoned to passion, haunts hunting’s status as the act most performative of exemplary, elite masculinity. Submission to passion undermines the ethical edifice that noble masculine privilege constructed for itself within the hunt’s circumscribed processes. The strength to resist the hunt’s private pleasures form a pillar of its purpose as a training ground to public duty. Temperance and moderation are the ethical imperatives that legitimize the political asymmetry inherent in early modern monarchy; self-control is the hallmark of the just governance of others. Peacham writes: “And albeit it is true as Galen saith, we are commonly beholden for the disposition of our minds, to the Temperature of our bodies, yet much lyeth in our power to keep that fount from empoisoning, by taking heed to ourselves; . . . to correct the malignitie of our Starres with a second birth.”38 These views were common across the Protestant northwestern periphery of Europe, dovetailing even with the responsibilities of Tycho Brahe as astronomer to Anna’s father, Frederik II of Denmark, which included the casting of natal horoscopes. As John Robert Christianson has shown, Brahe’s understanding of celestial influence did not rule out an orthodox Lutheran view on free will: “Men have something higher in themselves, which overcomes the heavenly and elemental influences,” Brahe writes in the Astrologia of 1591. “And the human being conveyed by his reason and manifold thoughts, and alignments, is not so easily transformed and moved, as the unreasonable beasts. But a few men more or less so than the others.”39

Such discourses privilege the cool head, the seat of reason, over the labile body natural, subject to the ebbs and flows of its passions. “Mind over matter” is a distinction of rank within the body analogous to the control of the sovereign over the state. As Jonathan Gil Harris has written: “The members of bodies natural and politic share a pathological predispensation to imbalance, discord and unruliness, the corrective to which is the beneficent, yet decidedly authoritarian, intervention of the soul and/or ruler.”40 The hunt, therefore, offered a means of profoundly fleshly self-fashioning, constituting, to coin Peacham’s phrase, a “second birth.”

The pedagogical theme extends to Anna’s spirited little hunting dogs (see detail, fig. 12).41 Claude Anthenais, drawing on the French name for the greyhound—lévrier, or hare-courser—suggests in his analysis of the portrait that the Queen is hunting hares (as appears to have been her custom, as we have already seen).42 Following this, I suggest that Anna’s dogs are young greyhounds that she is training in the field. Greyhounds began their training by hunting hares, as the hares’ ingenuity (their doublings and crossings) taught young dogs perseverance. Although not specifically identified as Italian greyhounds in these sources, black-and-white hunting dogs appear in both French and English cynegetic literatures. George Gascoigne writes: “Now in our latter experience in this kingdome [England], we find the white Dog, and the white dog spotted with blacke, to bee ever the best hunters, especially at the Hare.”43 Jacques Espée de Selincourt, in Le Parfait Chasseur, writes: “Of the three main kinds of dogs the English have, the largest and most beautiful are said to be of the royal race, and are white marked with black.”44 For those viewers familiar with these literatures, the portrayed scene could function as a witty allegory. Just as Anna teaches the young dogs of the English royal race to navigate the hunting field, so too she performs exemplary majesty for the young Charles, then in training to be the future king of the larger field of Great Britain.

Within this scenario, the privileging of reason over strength as the foundation of rulership persists. As the wiliest of all prey animals, the hare was especially a test of a hunter’s and her dogs’ intelligence and strategy. In the sole textual reference to women’s (and indeed scholars’) hunting practice that I am aware of, in the Boke of the Governor (1537), Thomas Elyot writes: “Huntyng of the hare with grehoundes is a right good solace for men that be studiouse, or them to whom nature hath not given personage or courage apt for the warres. And also for gentilwomen which fear neither sonne nor wynde for appairing their beauty.”45 Hares also possessed other cultural valencies. In his edition of Juliana Berger’s The Book of St. Albans, Gervase Markham writes: “The Hare is the King of al the beasts of Venerie, and in hunting maketh best sport, breedeth the most delight of any other, and is a beast most strange by nature, for he often changeth his kinde, and is both male and female.”46

This theory of the hare’s hermaphroditism was thoroughly debunked by Edward Topsell in his 1607 translation of Conrad Gesner’s magisterial zoological tract Historiæ Animalium; nevertheless, the myths of the bestiaries retained their cultural currency well into the seventeenth century.47 Animals’ special qualities were preserved in vernacular oral culture, and their stories were used to inspire young scholars to read their books, as Cleland recommends.48 John Robert Christianson has shown that Anna hunted hares with her sister Elizabeth; her father, Frederik II; and her mother, Sophia, as a young woman in Denmark.49 Hares may have had some special significance at the Danish court; Hans Knieper’s Kronborg workshop produced a series of tapestries portraying them, which are now lost.50 Within the Danish context, the hare may have been identified with Loki, who as the clever, shape-shifting, gender-fluid trickster of Norse mythology was perhaps the ultimate master of self-fashioning.

Genealogy and Ingenium

Hans Belting has argued that a shift in the concept of the portrait by the humanist artists of the Northern Renaissance during the sixteenth century revisioned the “Self” so that it was no longer understood as something fully contiguous with the body, but separate from it.51 Within the portrait, the physiognomic view of the body was gradually superseded by a new visual-textual rhetoric of the Self. While this new rhetoric served intellectual humanists and other members of the non-noble classes by articulating their claims to social status—and to representation—it was also co-opted by those with venerable dynastic genealogies, such as Frederick the Wise, as Belting shows.52 Within the courtly class, genealogy became paired with ingenium. A body’s fleshly, inherited nobility was crowned with the personal distinction conferred by the innate qualities of the individual: their God-given reasoning and creative powers. So James Cleland writes of James VI and I: “I maie affirme there is one like a Quintessence, above the foure elements, which containeth such wits, as appeare not to bee taught or informed by men, but infused by God; they are able in the twinkling of an eie, at the first motion to conceive, invent and retaine al things most accurately. Of such wits I have never seene, read or heard of one comparable to the King’s Majesty.”53

Of course, venerable genealogy retained its importance for the self-imaging of elites, since the association between noble blood and superior virtue only served to further legitimize their privilege. As James writes in Basilicon Doron, referencing the theology of traductionism (the theory that original sin is transmitted from parents to children): “For though, anima non venit extraduce [the soul does not come by traduction], but is immediately created by God, and infused from above: yet it is most certaine that virtue or vice will oftentimes with the heritage bee transferred from the parentes to the posteritie and run on a blood (as the Proverbe is). &c.”54 While a virtuous genealogy retained its importance to royal identity within hereditary monarchy, this inheritance was balanced and enhanced by the ruler’s individual, even divine attributes.

Similarly, for artists of all disciplines, ingenium was conceived as a God-given talent for originality, equipping an individual to create something brand new from the models available to him or her, rather than merely repeating them. The proper assimilation and phenomenological digestion of a rich array of precedents stored in the memory nourished the inborn genius, enabling it to surpass and perfect its models. The intertwining theories of imitation and innutrition taught that the assimilating and digesting of many precedent perfections, like the honeybee visiting many flowers, would assist student practitioners of painting, poetry, rhetoric, or indeed, rulership, to construct their own new and original styles. Peacham couches his advice to young nobles on developing their style by speaking in just these terms, while drawing on a series of examples of artisanal expertise:

For as the young Virgin to make her fairest Garlands, gathereth not altogether one kinde of Flower; and the cunning Painter, to make a delicate beautie, is forced to mixe his Complexion, and compound it of many colours; the Arras-worker, to please the eyes of Princes, to be acquainted with many Hiftories: so are you to gather this Honey of eloquence, A gift of heaven, out of many fields; making it your owne by diligence in collection, care in expreffion, and skill in digeftion.55

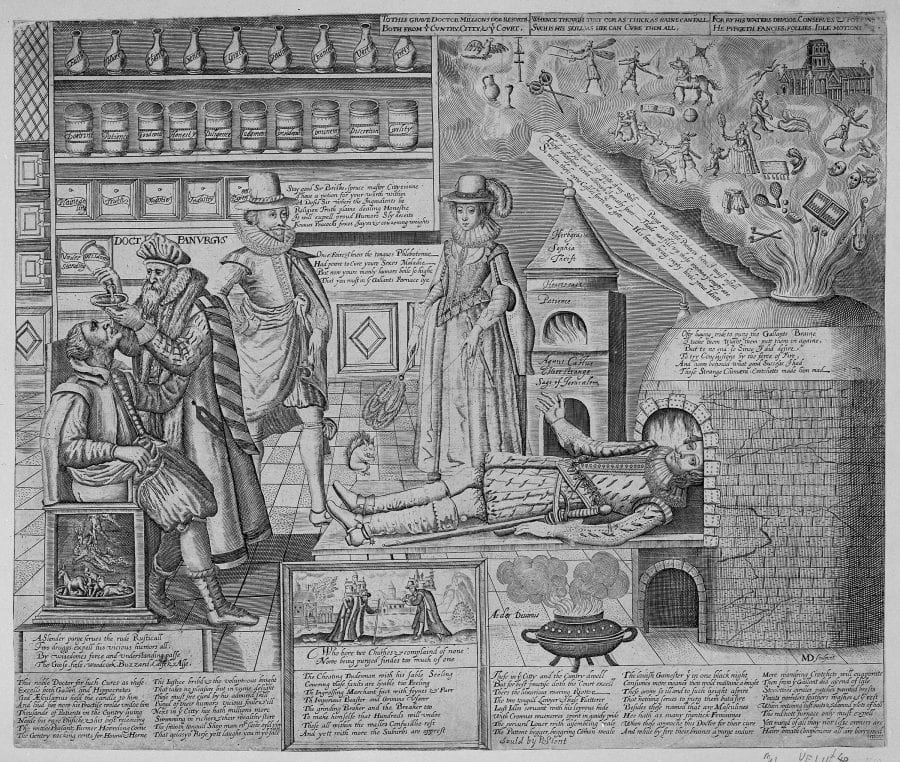

In the wake of Anna’s death, her portrait offered her son an image to instruct and nurture him. Selecting a diet within the humoral regimes that structured the early modern body was an act of self-fashioning in its most literal sense, affecting the quality and comfort of body and mind. So, too, selecting a diet of images was informed by the potential effects on the physical and mental interiority of the viewer. Consumption of food, drink, and art were all part of a “highly complex network of influences on character and health,” and all required the discipline of temperance.56 As Denis Ribouillault has noted, a taste for painting was not necessarily an untrammeled virtue.57 Indiscriminate “binging” on images without carefully selecting and properly digesting them could lead to dubious encounters with the early modern medical profession. This is demonstrated in a print in which patients of Dr. Panurgus are purged of a surfeit of images by variously scatological means (fig. 13). A well-to-do courtier’s head is steamed in an oven to evaporate the frivolous images that have congested in his brain. A rather less well-to-do client is purged of his poorly digested images on a close stool, or commode. The accompanying text states that “millions” have resorted to this grave doctor, suggesting that the fashionable consumption of high art could lead as often to widespread dangerous delusions as to virtuous erudition. This may seem rather prescient in light of Charles’s later career as perhaps the most discerning collector and commissioner of art the British succession has ever produced, and also as leader of the defeated Royalist armies.

Such graphic pastiches are dependent on the reception theory of the period, which argues for the transformative agency of the exemplary portrait. Richard Haydocke’s translation of Gian Paolo Lomazzo’s Trattato dell’arte della Pittura, Scoltura et Architettura (1584) maintained that painting had the power to move the beholder literally, and he conceptualized the body as a medium for the imprinting and storing of images, as Hans Belting has more recently argued.58 Haydocke writes: “So a picture artificially expressing the true naturall motions, will (surely) procure laughter when it laugheth, pensiuenesse when it is grieued &c.”59 He goes on to explain that a beholder will feel his appetite moved when he sees delicacies being eaten or will experience fury at a heated battle scene. A beholder before a portrait of exemplary majesty would, theoretically, experience his reception of an image physically and feel the literal impression being made upon him by the scene before his eyes. As Thijs Weststeijn has written, “Taken to the extreme, this means the beholder is supposed to ‘become’ the work, as ultimately he takes on the work’s qualities.”60 The image fashions the viewer.

Ingenium was thus linked dialogically with genealogy in all kinds of creative practice. As Aileen A. Feng notes in relation to poetry, “the relationship between the source texts and the new one should be modeled on that between a father and his son: a subtle resemblance, but not an exact replica.”61 A well-stocked visual memory is of central importance to both making and experiencing art, since much of its pleasure is in the recognition of the visual allusions that a work makes to its precedents. As Elizabeth Cropper has shown in relation to the Caracci family of painters:

Artists in the humanist tradition of painting . . . were just as concerned with inventing, disposing and ornamenting themes through allusive cross-references as they were with the representation of natural effects or the invention of new subject matter altogether. . . . Works of art relied as much, if not more, upon familial relationships with other works of art as they did on comparisons with living nature.62

Within this allusive culture, Anna’s portrait exceeds its place as a link in an aesthetic genealogical chain. According to this reading, Anna is no longer the passive subject of a portrait whose story narrates a prologue in an artistic succession, from Peake to van Somer to van Dyck, to which she is only somewhat incidental. Anna, by means of her portrait, intervenes and demonstrates her contributive agency within the historical process of the princely succession. As sitter, mother and queen, Anna’s portrait anticipates, even interpellates, the portrait of her son.

Concluding Thoughts

By reading into Anna’s pictorial genealogy, the rich and complex early modern cultures of the hunt, and contemporary theories of art making and reception, we are able to recognize a reciprocal dialogic engagement between van Somer’s Anne of Denmark and van Dyck’s Charles I. Van Dyck’s Charles may now be regarded as a material reception of van Somer’s Anne and as evidence of how Charles’s kingly self-fashioning was constructed in light of her example. This is not to minimize the contribution of either van Somer or van Dyck in taking forward the theme of the dismounted equestrian ruler portrait in new and innovative directions. Both artists’ authorship is clearly legible in the portraits they painted for their royal sitters. It would be unwise to assume that these artists, having trained in the richly creative and innovative tradition of the Low Countries, had no input into the composition of the works of art they painted. The intent of this article, rather, has been to reintegrate the queen and her son, the king, as thinking agents acting within this process and upon its artistic outcomes. Genealogy and ingenium have often been mapped against the royal sitter and the commissioned artist, respectively. This essay argues that both the possession of heritage and the powerful ability to fashion and create are qualities brought to bear by artist and patron in the production of these original portraits.

The queen, whose body has physically regenerated the dynasty and whose portrait provides the next generation with its perfect exemplar, is doubly figured as the ultimate reproductive medium. Her portrait is much more than a mere screen for the projection of monarchical and dynastic aura. The portrait’s witty composition should remind us that both the sitters and viewers of Renaissance court portraits were often more adept and erudite than historians have recognized, and that their splendid portraits contain greater political agency and self-awareness than is sometimes assumed.