Scholars have long recognized the formal significance of Claes Jansz. Visscher’s 1612 copies of the Small Landscape prints for the development of seventeenth-century Dutch landscapes. The prints, which were originally published in Antwerp in the mid-sixteenth century, represent the rural terrain of Brabant with a direct naturalism and topographic specificity that would later become a hallmark of Dutch Golden Age landscape prints and paintings. This article focuses on the content of the series and attempts to understand the Dutch market and appreciation for views of Brabant in the early seventeenth century. Published in the early years of the Twelve Years’ Truce, likely with the vast émigré population of Southern Netherlanders in mind, the prints visually restore Brabant to its pre-Revolt past of peace and prosperity at the same time as they stimulate hope for a reunification of this lost southern province into a new United Netherlands.

Claes Jansz. Visscher has long been acknowledged as a pivotal figure in the early development of seventeenth-century Dutch landscapes. Soon after setting up shop on the Kalverstraat in Amsterdam in 1611, Visscher began issuing a remarkable number of landscape prints that offered realistic views of the local Dutch countryside, quickly establishing himself as the leading publisher of Dutch landscape prints in Amsterdam.1 However, many of the earliest of these prints were not original series, nor did they depict Dutch locales. Instead, Visscher’s specialization in landscapes first took shape through a campaign to republish Flemish landscapes from the sixteenth century.

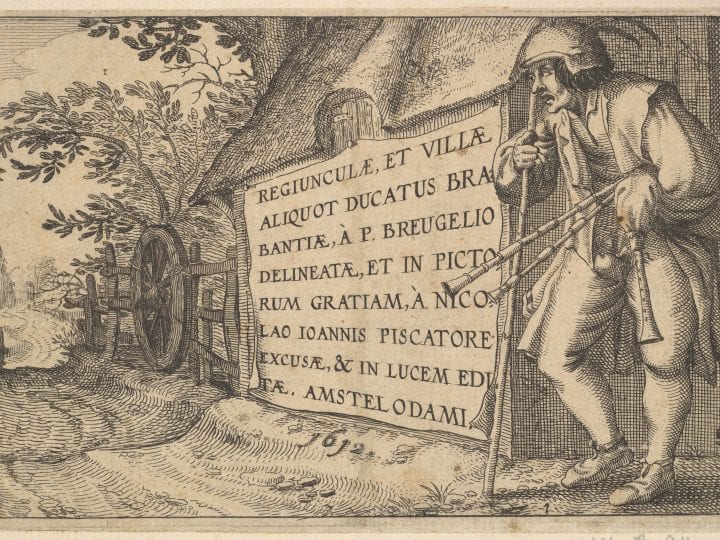

At the center of what we might call this “Flemish revival” stands Visscher’s copied set of the Small Landscapes, views of the Brabantine countryside and villages that were originally published in two sets by Hieronymus Cock in Antwerp in 1559 and 1561 (figs. 1–7).2 Unable to acquire the original plates for the series, which remained in Antwerp in the possession of the Galle printing dynasty, Visscher did the next best thing, copying twenty-six of the original forty-four views, which he published as a set in 1612, under the title Regiunculae, et Villae Aliquot Ducatus Brabantiae, with a newly devised title page, which will be discussed below. The views in the original Small Landscape series appear to depict particular places and to concentrate their visual focus on the local terrain itself. The two title pages that Cock issued with his original series assert that the views were in fact drawn “naer d’leven” and “ad vivum,” respectively – that is to say, from life (fig. 1).3 Cock’s Small Landscapes include only scant staffage, and the few figures that are included appear incidental and never distract from the primary focus on the locales themselves. This same sense of topographic specificity is communicated in Visscher’s copies. There can be no doubt that these small, humble views of country villages and rural farms, half a century old by the time Visscher encountered them, spurred the young printmaker and publisher to represent his native Dutch terrain with a similar simplicity and specificity and, in so doing, helped to usher in a new mode of naturalistic Dutch landscape imagery.4

According to many scholars, more than the particular content of the prints, it was the descriptive, almost documentary approach to rustic scenery in the Small Landscapes – that is, the formal example they set forth – that provided the artistic stimulus for Visscher’s subsequent production of local Dutch views.5 As this model of landscape migrated from prints to paintings, it influenced the distinctive development of Dutch Golden Age landscape more broadly. Visscher’s translations of the humble Brabantine views of the Small Landscapes, in other words, anticipated and indeed precipitated the new indigenous form of landscape art that emerged in the Northern Netherlands in the decades after their appearance.

Although Visscher’s copies of the Small Landscapes are integral in charting his well-known trajectory toward the creation of innovative native Dutch landscapes, this article will suggest an alternative perspective on the way these prints may have operated in the north when they were published there in 1612. Rather than conceiving of his copied views as revolutionary or new, Visscher almost certainly understood them as retrospective rather than innovative, as embodying and re-presenting a venerable older Flemish tradition as much as anticipating a new pictorial model for Dutch landscapes. The question then arises: why would Visscher have gone to such an effort to reproduce these old views and what resonances or associations might they have had for contemporary Dutch audiences? I believe there was good reason for Visscher, always the savvy businessman, to have been confident that old views of the Brabantine countryside would have found a receptive audience in Holland in 1612. Just three years into the Twelve Years’ Truce (1609–21), these prints offered a nostalgic invocation of the region of the Southern Netherlands that had so recently been ceded to the Spanish in the brokering of a temporary peace. Thus, in addition to or apart from the role their formal power played in transforming the artistic idiom of landscape in Holland, the specific topographic content of Visscher’s Small Landscapes recalled for Dutch audiences both an earlier era and a now-distant place.

To explore this hypothesis requires a careful examination of the prints themselves (figs. 8–15). Twenty-four of the etchings in Visscher’s series are copied from Cock’s original 1561 set. Along with a new title page, he also appended two additional prints at the end of the series. The last print, of a moated castle, has no precedent in Cock’s work and seems to be related to some of Visscher’s slightly later prints of nearby castles, while the penultimate print is a free copy loosely based on one of the views from Cock’s 1559 set.6 All the rest of Visscher’s prints hue closely to Cock’s original models, indicating that while Visscher augmented the series, he also sought to remain faithful in his reproductions to the original views.

It was a common practice among early seventeenth-century print publishers in both the Southern and Northern Netherlands to republish older plates.7 Visscher himself regularly bought up old plates and reissued them throughout the long duration of his career as a publisher.8 Nor were the Small Landscapes the only print series that he replicated when he could not attain original plates; he would later go on to produce copies of several other landscape print series, though this is, to my knowledge, the earliest instance of his doing so.9 Given how many secondhand plates were available in the north, including plates for Flemish landscapes, and his own skills as a landscape draftsman and etcher, it is perhaps all the more notable that Visscher went to the effort to produce new plates after these particular prints. He must have deemed them both significant enough to warrant being copied, with a broad enough appeal to garner a wide audience, and sufficiently difficult to obtain in Amsterdam to prove commercially viable – this despite the fact that the original prints had been reissued in Antwerp by Philips Galle in 1601 and his son Theodoor Galle some years thereafter.10 This suggests that the print markets in Antwerp and Amsterdam were isolated from one another, even after the Twelve Years’ Truce, to a degree that made copying the plates a reasonable and attractive scheme.11

Because he had to recreate the Small Landscapes rather than simply reprint existing plates, we can tell a great deal about what Visscher sought to maintain from the original prints and what aspects of the images he was willing to alter and adjust. Let us consider first the changes.12 Visscher numbered the prints in his series, thereby creating a clear sequence of views, while Cock’s sets had been issued unnumbered. Visscher’s versions are also smaller in scale than the original prints, measuring about 10 x 16 cm, compared to 13 x 20 cm. Although this slight reduction might have been a strategy to control costs (these smaller plates would require less copper), the reduced scale also makes the resulting views more compact and intimate. In addition to the overall reduction in size, Visscher also cropped most of the images at the edges, sometimes by tiny increments, sometimes to a more significant degree (compare figs. 2 and 9; 3 and 10; 4 and 11). These reductions tighten the centralized focus of the images by curtailing slightly their lateral expansiveness, bringing the views slightly closer to the viewer. Because of the reductions at the margins, the central views are now often more clearly framed by trees that rise along the edges, their foliage slightly fuller and softer, which suggests a record not just of a specific place but also a specific, fecund, season and atmosphere. These bushy trees create an enclosing boundary at the edges of the views, heightening the sense of quietude and intimacy they create for the viewer (compare figs. 3 and 10; 4 and 11). The greater concentration of Visscher’s scenes is also heightened by his treatment of the sky – his billowy clouds are more heavily defined compared to the stark blank skies or the horizontal hatching found in the original prints (compare figs. 3 and 10; 5 and 12). In most of Visscher’s copies, hatching fills in the top corners of the prints, transforming their rectangular format by establishing an oval framing device at the top that encloses the landscape below (compare figs. 6 and 13; 7 and 14).

The overall tone of the prints – in part because of their compression but also because of Visscher’s freer etching technique – is slightly darker or denser. While Cock’s original prints, etched and engraved by the van Doetecum brothers, are stark in their clarity and precise in their contrasts, Visscher creates larger swathes of deep shadow, particularly in the immediate foreground of his views, which results in a more dramatic, unified atmosphere. The few figures included in the copies are set out in silhouette against patches of light in the middle ground (compare figs. 2 and 9; 3 and 10; 7 and 14). The darkened foreground and lighter middle ground also help to more forcefully pull the viewer’s eye into the scene, an effect enhanced by the more strongly articulated lines in the curving sweep of the roads that frequently lead from the foreground into the middle distance.

In addition to these changes to the framing and atmosphere of the scenes, we see significant alterations to the staffage as well. Virtually all of Cock’s original figures have been replaced or removed, their positions and activities changed, and new figures added. Some take up typical rural activities. Visscher added fishing scenes to two of the prints, possibly a punning reference to his own name (figs. 12, 13).13 However, most of Visscher’s figures simply stroll or rest along a central road, with few references to any sort of work or toil. The figures in Cock’s series often appear as awkward afterthoughts too small for their surroundings. By contrast, Visscher’s occasional figures cohere seamlessly within their environment, their compositional integration and their easy repose heightening the sense of the pleasant peacefulness of these rural places (compare figs. 7 and 14).

For all these changes and adjustments, there is one important way in which Visscher was scrupulously faithful to his models. His copies are exacting in their accurate reproduction of the original architecture and arrangement of the views. Every building, indeed every window and wooden slat in every farmhouse, is assiduously recreated. Every fence, well, tree, and hedge appears again in precisely the same location, so as to maintain the organization and composition of each scene. Although Visscher’s etched lines and forms are slightly more irregular than those of the van Doetecums, there is an obvious effort to render each detail of these structures and their setting with diligent accuracy. Thus, while Visscher treats the aspects of the prints that establish space, atmosphere, and human presence with much greater latitude and freedom, he is at great pains to carefully replicate the specific topographic details of each scene. Visscher’s desire to remain true to the topographic content of the Small Landscapes is indicated not only in the views themselves but in Visscher’s title page (fig. 8). A large sheet tacked to the wall of a barn bears the title, which can be roughly translated as: “Some small residences and villas of the duchy of Brabant, delineated by P. Breugelio, and for the sake of painters engraved and published by Claes Jansz Visscher, Amsterdam.”14 While he might as easily have proclaimed the series to be rustic country views of less specific provenance, Visscher clearly identifies the views as Brabantine. He then begins his series with one of the only views that depicts an easily identifiable monument, the Roode Poort of Antwerp, further tethering the rest of series to this particular geographical setting (fig. 15).15 There is another notable feature to Visscher’s title page. He attributes the series to Pieter Bruegel, despite the fact that Hieronymus Cock did not identify the designer of the Small Landscapes at all, and Philips Galle had attributed them to Cornelis Cort in his 1601 edition.16 The large peasant holding a bagpipe and a walking stick placed next to the title sheet seems aimed at reinforcing this association with Bruegelian imagery. Visscher’s attribution might be interpreted simply as a canny commercial ploy to boost sales, given the resurgence in Bruegel’s posthumous reputation in the Netherlands at this time.17 But there was perhaps a further impetus. Just as the title page overtly states that these are views of Brabant, attaching Pieter Bruegel’s name to the series further authenticates its Flemish origins. This also underscores the idea that Visscher was not marketing these views as contemporary or new images; rather, he deliberately stressed their venerable provenance. Visscher’s title page thus functions both to locate and historicize his copies of the Small Landscapes by explicitly binding them to Brabant and to the past.

Visscher’s investment in recreating the Small Landscapes suggests that he sensed a strong market for these retrospective Flemish images in the Dutch Republic. Indeed, he undertook a campaign to republish several other sixteenth-century Flemish landscapes around the same time. He likely purchased the plates for several series of landscapes, originally published in Antwerp by Hans van Luyck, from the estate sale of Cornelis Claes in 1610.18 These included the By Antwerpen series, twelve landscape views ostensibly representing the countryside around Antwerp, engraved by Adriaen Collaert after designs by Jacob Grimmer and first published by van Luyck around 1580. He also acquired the plates for a series of views of the environs of Brussels, engraved by Hans Collaert I and published by van Luyck around 1575–80. Visscher, following Cornelis Claes, attributed this series, perhaps opportunistically, to Hans Bol, another Flemish artist whose considerable posthumous reputation in the north would have added cachet to the series.19 Visscher’s editions of these Flemish series include his name as publisher and are undated, but it is likely that he republished them within a few years of purchasing the plates, that is to say, exactly contemporaneous with his copies of the Small Landscapes. As a result of this campaign, Visscher was able to offer a substantial number of old Flemish landscapes for sale in his shop, all at about the same time. Although varied in compositional arrangement and the degree of specific detail, all of the series present, or purport to present, topographic views of the Brabantine countryside. The sheets of the Brussels series are even carefully labeled with the name of each location depicted. Visscher’s Small Landscapes are therefore neither anomalous nor coincidental but must be viewed as part of his larger program to revive a particular type of sixteenth-century Flemish topographic landscape imagery. With the publication of these series, Visscher essentially cornered the market in early seventeenth-century Amsterdam for such Flemish views.20

Visscher would not have invested such effort and capital both in acquiring and copying plates for Flemish topographical landscapes without a firm conviction that these series would appeal to a wide audience and prove commercially profitable. One of Visscher’s intended audiences for the Small Landscape copies, and likely his other Flemish series, was other artists. He specifically dedicated the Small Landscapes to other artists on his title page: “in pictorum gratiam.”21 As exempla for artists, including painters, these prints disseminated a direct, documentary approach to depicting the landscape in a realistic, immediate way. In this way, the prints, not unlike sketches and drawings, served as tools, workshop models to be referred to in the course of composing other works. Visscher clearly foresaw the generative potential of the Small Landscapes; though there are no known Dutch prints or paintings that directly employ motifs or compositions from the Small Landscapes, there can be little doubt of their later artistic impact on Dutch landscape artists, beginning first and foremost with Visscher’s own Dutch landscape prints, to be discussed in detail below.22

It is, however, extremely unlikely that Visscher’s commercial goals for these series extended only to other artists. As Nadine Orenstein has cogently argued, Visscher’s success in this field was due in large part to the fact that his landscapes could appeal to different segments of a wide art-purchasing market in a variety of ways.23 Scholars have long debated the appeal and significance of the newly naturalistic and topographic Dutch landscapes that appeared in the early decades of the seventeenth century in the wake of Visscher’s enterprise. While some have read these landscapes in symbolic and religious terms, seeking to determine the scriptural significance of particular elements or structures within the landscapes, others have suggested a more holistic interpretation of the genre in a broadly Calvinist context as records and celebrations of God’s natural creation.24 Others have pointed to the ways that these landscapes often called forth recent history and memory and helped to shape the contours of an emerging, specifically Dutch, geographical and cultural identity.25 Still others argue that Dutch landscapes must be understood within more specific urban contexts, in which both local pride and pleasure in rustic retreat shaped viewers’ reactions to naturalistic views of their lived environment.26

Throughout these discussions, there has been little effort as yet to determine and elucidate the particular resonances of Visscher’s Small Landscape copies and his other reprinted Flemish landscapes, which were, after all, not views of local Dutch places. It is difficult now to reimagine how they were received in 1612 without the hindsight of their later artistic and formal influence, that is, without locating them in the formative first stages of an artistic trajectory that we know leads to the flourishing Golden Age of Dutch landscape. However, audiences in 1612 could not yet have foreseen this trajectory and therefore must have viewed the Small Landscapes in other terms. For them, the landscapes’ resonances would not have been prospective or Dutch, but rather retrospective and Brabantine.

One especially receptive audience would have been homesick Southern Netherlanders who emigrated to the north in huge waves from the 1570s on.27 Jan Briels has calculated that at least 46,000 people emigrated from Antwerp to the north between 1578 and 1589 alone, mostly settling in Amsterdam. In some northern towns and cities, southern émigrés as much as doubled the local population. These refugees brought with them a taste for art and luxury decorations, which as Eric Jan Sluijter has shown, proved an enormous spur for both the importation of paintings from Antwerp, as well as the indigenous production of paintings by émigré and northern artists alike. He stresses the nostalgic appeal of the Small Landscapes in particular for immigrants and has placed these images in the context of a wide array of textual sources pointing to a similar nostalgic impulse.28 There can be little doubt that Visscher, ever responsive to potential audiences for his prints, must have recognized the commercial possibilities in a vast, culturally sophisticated immigrant population that was both predisposed to patronize the arts and homesick for the south.29 For them, his Small Landscape copies would have directly and realistically recalled the rural regions of their abandoned homeland with a simplicity, candor, and apparent accuracy unmatched in any other prints then available. The invitation to walk into and through the villages and countryside of Brabant proffered by the prints made this distant region visually present and accessible.30

However, the peaceful virtual tour constructed by the prints does not depict the Brabantine countryside as it existed in 1612. Devastated by the dislocations and depredations visited upon it during the preceding decades of war, Brabant’s rural terrain had been transformed by the turn of the century into a wasteland that recovered only haltingly in the years of peace that the truce granted.31 Rather than documenting these true conditions, Visscher’s copied series replaced the present reality with an ideal reconstruction of the region as it might have been known to immigrants in times past. This phenomenon is not unlike that noted by Anna Knaap in her discussion of views of rustic Dutch subjects and terrains from the early seventeenth century. With reference to Haarlem in particular, she notes that “during a period in which the Haarlem countryside underwent significant economic changes, artists rarely depicted any industrial innovations in their work. Eschewing the countryside’s entrepreneurial aspects, they rendered it as a place of pleasure, stability, and communal harmony.” Rather than documenting and embracing any precipitous and uncertain changes in the appearance, use and significance of the actual landscape, artistic renderings of the landscape might be characterized rather as essentially conservative and retrospective.32 Fueled by a powerful nostalgia for a lost place and a time gone by, Visscher’s copies of the Small Landscapes promised audiences just such a retrospective journey, the opportunity to travel back in time as well as to traverse the widening distance between north and south.

This resonance would have been particularly poignant for immigrants in the north, who still held fast to the dream of a reunited Netherlands. Although without political representation in their adopted home in the north and therefore without an influential voice in political life at this time, Southern Netherlanders were among the strongest supporters of the continued war against Spain in the hopes that this would result in the restoration of the seventeen provinces into a single body politic.33 While the Twelve Years’ Truce had finally brought a cessation to the hostilities between the Dutch and the Spanish and provided a de facto acknowledgment of the political legitimacy and independence of the new United Provinces, it also ratified the territorial loss of Brabant, Flanders, and the other southern provinces to Spain, a loss that had been a practical reality since the fall of Antwerp in 1585 but that was nonetheless still keenly felt in 1609.34 Southerners certainly had a great deal at stake in the debate on the future course of the war, hoping even after decades of assimilation into northern Dutch culture and society for the freedom to return to their native lands. This became increasingly urgent and fraught over time, since the Southern Netherlands and its inhabitants were, with the passing of time and the growing political, ideological, cultural, and religious differences between north and south, becoming increasingly foreign, or “hispanicized,” according to Dutch popular opinion.35 The ambivalence and growing complexity of the immigrants’ relationship to their own lost homeland were entirely elided in Visscher’s copies of the Small Landscapes, which offered instead a reassuring and familiar memory that served simultaneously as a visual promise of peaceful restoration and of seamless reintegration.

Pierre Nora’s conception of lieux de memoire is particularly apt in this context. He theorizes that what he calls milieux de memoire, or active sites of cultural memory that are inhabited and experienced in the present, as in ritual, can be transformed into lieux de memoire, or fixed vestiges of a cultural past, when they are no longer actively experienced in the present. These lieux de memoire are essentially commemorative and nostalgic, creating a discontinuity between the present and the past.36 This is akin to the process of distancing that southern immigrants encountered in the early seventeenth century when faced with the breach between their current lived experience within the Dutch Republic and their nostalgia for their past homeland. The Small Landscape prints might well have served as a visual lieu de memoire, by which images of the Brabantine countryside became a locus for consolidating memories of a past now disconnected from a present, lived experience.

If displaced southerners were especially invested in the struggle for Netherlandish unity, the Twelve Years’ Truce elicited a broader ideological interest in and debate about the fate of Brabant and the southern provinces. Although the main points of contention in the two years of negotiations that led up to the signing of the truce and in the resumption of war in 1621 focused primarily on economic and trade concerns rather than territorial ones, factions within the Republic nonetheless found it expedient to continue to promote the idea that the war was primarily driven by a desire to free their Southern Netherlandish brethren from the yoke of Spanish oppression.37 This position was also forcefully promulgated by the hard-line Protestants who sought to stem the perceived tide of Catholic dominion spreading across Europe, though this militant Protestant ideology was more concerned with confessional freedom than with territorial reconquest and political reunification.38 Even as the actual reunification of the Netherlands as a single nation became less and less likely from a pragmatic political perspective, the concept of natural Netherlandish unity sustained its ideological force. The early seventeenth century witnessed a surge in pamphlets, songs, popular plays, and prints promoting the idea of “Netherlandishness.”39

Maps were one of the most powerful formats in which ideas of Netherlandish solidarity found visual form in the wake of the Twelve Years’ Truce. In particular, Leo Belgicus maps, which had long represented the seventeen provinces bound together within the outline of a lion and which were published in large numbers in the United Provinces, represented the Netherlandish provinces as united rather than sundered.40 The Leo Belgicus map that Visscher himself published sometime between 1611 and 1621, titled “Novissima, et Acuratissima Leonis Belgici…,” explicitly celebrates the peace and prosperity brought about by the truce (fig. 16).41 At the lower left, two female personifications of the Northern and Southern Netherlands, labeled “t’ Vrye Neerlant (the Free Netherlands)” and “t’ Neerlandt onder d’Aertshartogh Albertus (the Netherlands under Archduke Albert),” embrace one another and trample “d’Oude Twist (the Old Dispute),” beneath their feet. Around them, allegorical scenes extol the flourishing arts, trade, agriculture, and science and the thriving cities that resulted from the peace. The central lion drives the tip of a sword into the ground. From its hilt hang two medallions inscribed “for twelve years” in Latin and Dutch, referring to the years of peace guaranteed by the truce. To accentuate this point, at the bottom right corner slumps a figure in armor named “Sleeping War,” the lion’s sword thrust just behind him as though pinning him to the spot. The coats of arms of all seventeen provinces border the top of the map and twenty small views of both northern and southern cities decorate the two sides. Just as these framing devices suggest a unified territory, the map embodied within the contours of the lion joins the seventeen provinces together into a single, vital entity. This map bespeaks the optimism engendered by the cessation of hostilities and the prospect of peace, as well as the residual faith that the seventeen provinces of the Netherlands in some essential way were – and would continue to be – a united land, restored rather than divided by the truce.42

Visscher’s copied Small Landscapes perhaps reflect the same optimistic spirit. Although neither Visscher’s title page nor the prints themselves contain overt or direct references to contemporary attitudes toward Netherlandish reunification, recent history and the debates surrounding Brabant and the Southern Netherlands could not but have informed the perceptions of contemporary viewers of the prints. By recreating views of an older Brabantine countryside, one not yet marred by the depredations of war, and circulating them at a moment when hopes were highest for a broad renewal of prosperity, Visscher offered Dutch audiences a vision of a past landscape of peace and tranquility that at long last, at least for a brief period, seemed once again within reach. Relinquished to the Spanish, Brabant was in a real sense quite removed from the United Provinces, but in their direct, unmediated format and composition, Visscher’s Small Landscapes brought this southern province to the north with a visual immediacy that belied the political rift that separated the two. In the context of the nascent Dutch Republic, the prints might imaginatively restore and reanimate the lost unity of the Netherlands by offering viewers the opportunity to enter and traverse – visually, at least – this lost region to the south. By heightening the views’ sense of intimate, placid harmony, while carefully replicating their topographic content, Visscher’s series reconstructed an older, more peaceful Brabant that had existed prior to the long intervening years of war, eliding the very conflict that had disrupted and splintered the Netherlands from its previous unified state. At the same time, by making this Brabant appear decidedly present and proximate to contemporary Dutch audiences, the prints make a visual case for the natural and geographic connection conjoining the north and the south and thereby reinforce the justness of a fundamental national bond.

At precisely the same time that he issued his copies of the Small Landscapes, Visscher was also working on an analogous set of views of the rural surroundings of Haarlem, known as the Plaisante Plaetsen (figs. 17–20). This series of twelve etchings includes an elaborate title page and a table of contents identifying each of the scenes that follows. Although undated, the Plaisante Plaetsen have been convincingly dated between 1611, when Visscher began operations in the Kalverstraat, and 1613.43 In an important sense, Visscher’s Plaisante Plaetsen are the perfect pendant to his version of the Small Landscapes. It is immediately evident why the two series are so often paired by art historians, since Visscher’s Haarlem views are heavily indebted to the compositional logic and apparently unfiltered realism of the Small Landscapes.44 The two series share the same dimensions, suggesting that they could be easily collected together. As in the Small Landscapes, Visscher encourages the viewer of the Plaisante Plaetsen to explore the rural surroundings of Haarlem through a virtual tour of particular spots in the local countryside. His carefully orchestrated sequence of views is numbered and labeled in the table of contents, with a view of Zandtvoort at the beginning of this visual journey (fig. 17). The prints move in a wide arc from south to east to north around the outskirts of Haarlem, offering views of dunes, inns, woods, and bleaching fields along the way. Despite the resolute topographic specificity with which the prints distinguish the terrain of Holland from that of Brabant, the viewer is invited to enter the views of both series along similar roads leading out from the foreground (compare figs. 14 and 18). Resemblances in the rustic architecture and the mundane activities of the peasants and wayfarers encountered within the views suggest the comparable nature of rural life outside Antwerp and Haarlem (compare figs. 9 and 20; 10 and 19). The Plaisante Plaetsen share with the Small Landscapes their matter-of-fact presentation of mostly unremarkable rural structures in an immediate and naturalistic manner that engages the viewer directly.45 Taken together, as they must often have been, the Plaisante Plaetsen and the Small Landscapes suggest a visual parity and conformity between the two regions they record.

Visscher’s transposition of the pictorial model of the Brabantine landscapes to his local views of Haarlem points not only to the likeness between the two regions but also to a deeper thematic union. As with the views of towns and coats of arms, north and south, that frame his “Leonis Belgici” map, Visscher’s Brabant and Haarlem series mirror one another and make a visual case for the natural and topographical correspondence that conjoined the two regions. In turn, this natural unity evokes a continuity of community that it was believed once bound the seventeen provinces together and that some hoped might yet be reestablished. The rural lands around Antwerp and Haarlem appear as two parts of the same natural territory and as complementary regions within a common national body. Because of the naturalism and seemingly unmediated directness of these rustic landscapes and the immediacy of the visual experience they engender, the two sets of prints together hold forth a promise of objective veracity that makes the claim for unity all the more visually and ideologically compelling.

This article has suggested the multivalence of Visscher’s 1612 version of the Small Landscapes within the artistic, cultural, and political context around the time of the Twelve Years’ Truce. On the one hand, the copied prints were deliberately retrospective, being recreations of older images attributed to the past great master Pieter Bruegel that were part of Visscher’s broader program of Flemish landscape print republication; on the other, they provided the artistic impetus for Visscher and other artists in his wake to create very immediate views of their own local landscapes. The copied Small Landscapes might have evoked nostalgia for a lost home and past, particularly among the enormous population of southern immigrants and refugees who took up residence in the north. At the same time, the Brabantine views, by making this southern countryside palpably present, offered hope for a restoration – if only in print – of the inherent unity of the Netherlands, particularly when considered in tandem with Visscher’s contemporaneous Plaisante Plaetsen prints. In these ways, Visscher’s copies of the Small Landscapes were at once old and new, occupying a critical fulcrum between the Southern and Northern Netherlands, between artistic tradition and innovation, between aesthetic experience and ideological meaning, between a retrospective view of the past and hopes for the future. As such, they suggest the complexity of the migration that these Flemish topographic landscape prints underwent in their transference from Antwerp to Amsterdam in the early seventeenth century and the attendant revisioning of place, memory, and nation that they enabled for contemporary audiences.