When Carol Purtle published her influential study of Van Eyck’s Marian paintings, it ran counter to a growing methodological tendency, which has become increasingly evident over the last twenty years or so, to favor iconographically minimalist interpretations of early Netherlandish paintings whereby only obvious symbols are accepted as necessary or valid. This article argues that this reductionist trend is in direct contradiction of the allusive and responsive ways in which Eyckian paintings communicate symbolic meaning visually, using a distinctive optical language which establishes a fluid integration of description and meaning. The following discussion demonstrates how this language operates on a symbolic level using the example of a single object–the pair of spectacles in The Virgin and Child with Canon Joris van der Paele (completed 1436).

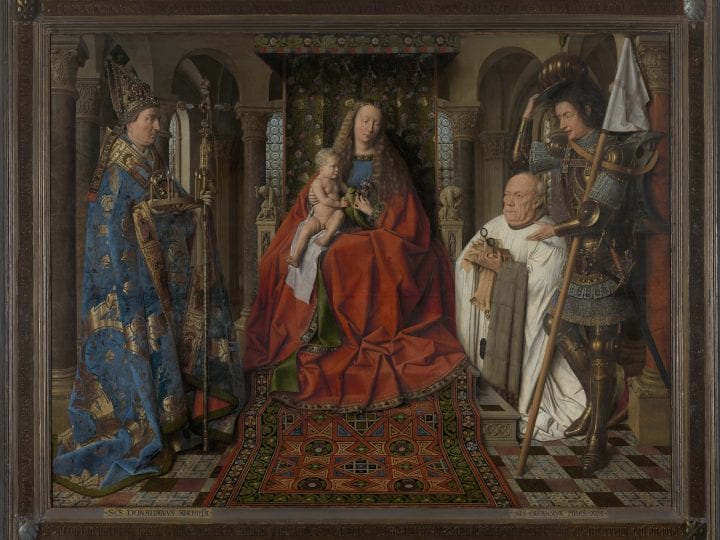

Jan van Eyck’s Virgin and Child with Canon Joris van der Paele (completed 1436; fig. 1) is arguably the most elaborate and impressive demonstration of the artist’s fascination with optical concepts and effects.1 The painting depicts Van der Paele, a wealthy canon of the Church of Saint Donatian in Bruges, kneeling before the enthroned Virgin and Child, flanked by Saint George and Saint Donatian. The group occupy the dark interior of a church, implicitly illuminated by a source of light in front of the painting (to the upper left) which appears to activate color, tone, and texture–from the gold threads of Saint Donatian’s brocade to Saint George’s shiny armor–as it is reflected, re-reflected, and refracted from different surfaces.2 In his left hand, Van der Paele clutches a manuscript, from which he was apparently reading just moments before, and, in his right hand, he holds a pair of spectacles (fig. 2).3 Their frame casts a shadow onto the book and the text beneath one of the lenses is visibly distorted.

The following discussion uses the canon’s spectacles to analyze how the visual intentions of the painting, or more specifically its descriptive language, control or inform our interpretation of symbolic meaning. My selection of this particular, apparently insignificant, motif has two (related) purposes: first, as the canon’s spectacles have to date not received significant comment in analyses of the painting, I would like to redress this apparent oversight; and second, as an example of the kind of optical device that Van Eyck was clearly interested in, I would like to demonstrate how symbolic and descriptive concerns are integrated as part of the painting’s optical language. The central argument is that Van Eyck’s engagement with optical concepts and effects facilitated a uniquely Eyckian iconography characterized by a fluid and integrated relationship between symbolic ideas and the means of their visual expression.

Literalist versus Multilevel Symbolism

The essential tenet of the iconographically minimalist approach that has dominated recent scholarship is that where a literal, normative explanation for an object is sufficient to explain its presence, symbolic meaning is both unnecessary and unlikely (the basic principle of Ockham’s Razor).4 This explanation could certainly apply to the spectacles in Van Eyck’s painting, which were presumably intended to refer to a pair actually owned and used by the canon. Although the painting itself provides the only evidence of Van der Paele’s spectacles, the documentary record offers several circumstantial reasons why he might have needed them: he may, for example, have required them for reading, as a result of the onset of presbyopia (age-related farsightedness); or he may have experienced problems with his vision as a result of the medical condition (temporal arteritis?) that had prevented him from regularly attending Matins from 1431 onward.5 Alternatively, he may have required them much earlier in life to aid his work in the papal curia at Rome, where he had served as an abbreviator (scriptor) from 1396.6

For those scholars content with a literalist explanation, any one of these possibilities would presumably be sufficient to explain the significance of this apparently incidental detail. In reference to these biographical circumstances, it seems likely that the spectacles refer visually to (or symbolize) his failing health or his occupation–or perhaps both simultaneously. There are, however, two substantial problems with positing biographical realism as the sole explanation: first, whether Van der Paele owned spectacles or not, the decision to be pictured with them was, at this time, highly unusual; second, reading the spectacles in such a strictly nonsymbolic way runs counter to the way in which the painting encourages the viewer to recognize far more fluid relationships between physical objects and symbolic ideas.

In response to the first of these two problems, it is significant, yet only rarely noted in art-historical literature, that Van der Paele is the earliest known patron in early Netherlandish art to be pictured with a pair of spectacles. It is also striking that other patrons–some of whom must have worn spectacles in real life–apparently did not follow his example, as no other fifteenth-century portraits survive which show this same motif.

The textual record provides a very clear explanation for this relative invisibility of the device in the visual arts; generally speaking their owners were reluctant to openly display their reliance on eyeglasses. Duke Francesco Sforza of Milan expressed what apparently is a fairly typical sentiment among those who, usually through old age, became reliant on glasses. Writing to his ambassador in Florence to request thirty-six pairs in October 1462, the duke was quite careful to add the following disingenuous qualification: “We inform you that we do not want them for our use because, thank God, we do not need them.”7 Similarly, Petrarch in his Letter to Posterity laments: “For a long time I had very keen sight which, contrary to my hopes, left me when I was over sixty years of age, so that to my annoyance I had to seek the help of eyeglasses.”8 In a similar vein, the privy seal scribe Thomas Hoccleve admitted in his Ballad to my Gracious Lord of York (1411) that despite having strained his eyes for twenty-four years, he was too proud to wear spectacles.9

So what, we might reasonably ask, was the motivation behind Van der Paele’s evidently unusual, if not unprecedented, decision to be painted with his spectacles?

As the following case study will demonstrate, the answer to this seemingly straightforward question raises a number of important theoretical issues (and problems), beyond biographical realism and social connotation, concerning the way in which painted objects that are not obviously symbolic direct and engage meaning in Van Eyck’s paintings.

Spectacles as Painted Symbols?

Van der Paele is shown holding his spectacles over a manuscript, apparently using them to mark his place in the text he was presumably reading just moments before. This implied action provides a visual link with a chain of gestures (see figs. 1 and 3), leading from Saint George’s outstretched left hand to Christ’s right arm, each engaging the relationship between a series of associated held objects.

The manuscript and spectacles provide a crucial narrative indication to the viewer that Van der Paele has turned from his reading to gaze upon the Virgin and Child. Beyond their narrative function, however, the spectacles are also a visual counterpart to the openly symbolic objects held by Christ and His mother–the parrot and the bouquet of flowers (fig. 3). These two related objects would almost certainly have been associated in the minds of some fifteenth-century viewers with symbolic ideas. The red flowers held by Christ and the Virgin are (single) carnations (Dianthus ceryophyllus), which were commonly known as nagelbloem (nail flower), because they resembled the serrated edges of a medieval nail.10 The white flowers, as John Ward pointed out, are probably members of the mustard family, whose Latin name is Cruciferae.11 These symbolic references to the Passion and the Crucifixion would therefore have been quite openly accessible to those viewers able to identify the flowers in the bouquet.

Paradoxically, the parrot is both the most obviously symbolic motif in the painting and yet the most difficult to explain in reference to ideas reflected in contemporary texts. On the one hand, its visual conspicuousness clearly demands explanation outside of the interests of realism. On the other hand, the most plausible symbolic explanation scholars have yet advanced for this motif relates to a rather obscure text–Franciscus de Retza’s Defensorum inviolatae virginitatis Mariae–in which the author asks, “If a parrot has the power from nature to say Ave, why might not a pure Virgin conceive through (the word) Ave?”12 As there is no reason to suppose that Van Eyck would have been familiar with this particular text, it was most likely not the direct source. However, de Retza’s text does appear to reflect an existing belief that parrots greeted people with the word Ave. Much like the explanation for the flowers, therefore, it is quite plausible that the basic symbolic link between the parrot and the archangel Gabriel’s words at the Annunciation was not textual, but familiar and “open” to a contemporary audience on the level of linguistic association and commonly held, or popular, beliefs.

Van der Paele’s spectacles were probably not intended to operate on the same symbolic level as the objects held by the holy couple. Nevertheless, their visual association with those objects and the connection they establish between the act of prayer and the visible manifestations of its content (by which I mean both the “vision” of the Virgin and Child and the painting itself) suggests that their significance is more than literal.

One plausible interpretation, which derives from Craig Harbison’s view that Van der Paele is witnessing a visionary embodiment of his prayer, suggests that the spectacles point to the canon’s weak bodily vision, emphasizing his departure from sensory experience.13 According to another scholar, he has “not simply departed from external visual input…but has entered a meditative state that excludes sensory stimulation altogether.”14 Although apparently tenable in the context of this particular image, there is no visual or textual evidence that spectacles carried the kind of symbolic meaning these theories propose. Although Van Eyck was, of course, capable of iconographic ingenuity and invention, it is very unlikely that this broad association of eyeglasses with vision, at least not in the modern sense of the word, was available to him in the 1430s. Whereas today we use spectacles as correctives for both farsightedness and nearsightedness, prior to the 1460s they were used exclusively for close work–primarily reading. As suitable concave lenses (for the correction of myopia) had not yet been developed (these came probably in the 1460s), spectacles’ primary association was not with vision generally but with enlargement and the clarification of text.15 The majority of early textual references to spectacles specify their application as a reading aid, often describing how they make fine writing look bigger.16 The Venetian guild regulations, for example, refer to “glasses for the eyes for reading.”17 Their relationship to text and reading is also reflected in visual culture; as far as I am aware, all images of spectacles from the first half of the fifteenth century are associated visually with the act of reading. (This affiliation was reinforced by the way in which spectacles were often held directly over text, not necessarily held up to the eyes).

The majority of images that include representations of spectacles and which would have been potentially available for either Van Eyck or his patron to see do not make obvious iconographic use of the motif. There was a tradition in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries of depicting saints, occasionally in full-page miniatures but more usually in the historiated initials of manuscripts, reading or writing with the aid of spectacles (see, for example, fig. 4). Most of these images depict one of the evangelists writing, but there is otherwise no consistency in their appearance; no particular saint can be identified as having spectacles as an attribute. There is, therefore, no reason to suppose that this tradition reflects anything more than their use in (contemporary) reality, probably disseminated in some cases by the reuse of common visual models or figure types. More importantly, beyond the broad association of lenses with text, these images do not appear to share the same concerns as Van Eyck’s patron and painting.

There was, however, a visual tradition, which Van Eyck may have known, in which the association between spectacles and the enlargement of text for reading takes on an additional symbolic meaning that, in the context of a Marian iconography, is much closer to the concerns of Van der Paele’s painting. Before analyzing the canon’s spectacles, it is necessary to outline this iconographic tradition in relation to a few key examples.

Between the last quarter of the fourteenth century and the first quarter of the sixteenth century, in excess of forty images of the Dormition of the Virgin are extant from northern Europe that depict an apostle holding or wearing a pair of spectacles.18 In a manner comparable with Van Eyck’s painting, some images, such as the ca. 1480 engraving by Martin Schongauer (fig. 5), show the spectacles being held directly over a text and how the lens distorts the words beneath (although the text itself is never made legible). In other examples, such as the Death and Coronation of the Virgin miniature from the Bedford Hours (ca. 1410-15; fig. 6), one of the apostles (here above the Virgin to the left) is shown wearing the spectacles while reading. From the earliest to the latest examples and across different media (including panel painting, sculpture, manuscript illumination, and engravings), the iconography is consistent: the apostles, gathered around the Virgin’s deathbed, are participating in the sacrament of Last Rites. Alongside the apostle with spectacles, one usually holds a lighted candle, one holds a palm frond, and another, dressed in a priest’s alb, prepares to scatter holy water from an aspergillum.

The objects that are most consistently depicted in these scenes are not the usual identifying attributes of the apostles (although Saint James can sometimes be identified by his scallop shell), but symbolic devices relating to the Virgin and the account of her death. The most likely source available to artists for the narrative, and the details it contains, was the Golden Legend (written before 1264), in which the Virgin’s dormition is included as part of the narrative cycle of her assumption. According to this text, the candle–probably the most consistent of the details in Death of the Virgin images–refers to the words of Saint Peter: “Rejoice spouse of the heavenly bridal chamber, three-branched candelabrum of the light from on high, through whom the eternal clarity is made manifest.”19 Similarly, the palm John is sometimes shown holding refers to the one given by the angel to Mary: “The angel gave the Virgin a palm branch sent from heaven as assurance of victory over the corruption of death, and the clothing for her burial, and then repaired to heaven whence he had come.”20

Following the Golden Legend text, a number of images, including two manuscript illuminations by the Bedford Master (Châteauroux, Bibliothèque municipale, ms. 2, fol. 282v, and British Library, Add. 18850, fol. 89r), combine Mary’s dormition and assumption in a single scene (this is sometimes divided into two tiers, as in the Bedford Hours). In those images that show only the Dormition of the Virgin, spectacles are employed exclusively in scenes where Mary prepares for her soul–often represented as a doll-like child–to be received by Christ. (It should be noted that the phrase “Death of the Virgin” is often used generically in reference to scenes at the end of her life: her farewell to the apostles, funeral, and transitus.) The explanation for the apostle with spectacles, I believe, rests with the following lines in Jacobus de Voragine’s text, which immediately precede the moment when the Virgin’s soul leaves her body:

Then all those who had come with Jesus softly sang, “This is she who knew no bed in sin; she shall have fruit in the visitation of holy souls.” Mary then sang about herself, saying, “All generations shall call me blessed, because he that is mighty has done great things for me, and holy is his name.” The cantor, taking a higher pitch, intoned: “Come from Lebanon, my spouse, come from Lebanon; thou shalt be crowned.” And Mary: “Behold I come! In the head of the book it is written of me that I should do thy will, O God, because my spirit has rejoiced in thee, God, my saviour.”21

The author, basing his account on Pseudo-Dionysius’s Book of the Names of God, describes how the Virgin on her deathbed sang two verses of the Magnificat, before giving up her soul to Christ. Although taken from the Visitation narrative in Luke 1, the Magnificat was a reassertion, at death, of her role in Christ’s birth. Furthermore, from a doctrinal standpoint these two events were closely linked, as had she not died, doubt would be cast on the truth of the Incarnation.

As Judith Neaman has demonstrated in relation to the thirteenth century, the verb “to magnify” had the same primary and secondary meanings in Greek, Latin, and Hebrew that it retains today in all modern languages: while its primary meaning was metaphorical and biblical, meaning “to praise, exalt or extol,” its secondary meaning was literal and optical, meaning “to enlarge or amplify” (either by size or number).22 Furthermore, the act of magnification had a particular significance to the Virgin, since the Magnificat is itself a testament to her magnifying role in Christ’s Incarnation. As Neaman points out, the canticle expresses multiple transformative concepts of magnification, including praise of the Lord’s name and the Virgin’s name, elevation of social status, and multiplication in number:

My soul doth magnify the Lord.

And my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour.

Because he hath regarded the humility of his handmaid; for behold from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed.

Because he that is mighty, hath done great things to me; and holy is his name.

And his mercy is from generation unto generations, to them that fear him.

He hath shewed might in his arm: he hath scattered the proud in the conceit of their heart.

He hath put down the mighty from their seat, and hath exalted the humble.

He hath filled the hungry with good things; and the rich he hath sent empty away.

He hath received Israel his servant, being mindful of his mercy:

As he spoke to our fathers, to Abraham and to his seed for ever.23

Christ magnified Mary in elevating her from handmaiden to Mother of God. “In making her His instrument…He magnified her flesh even as her soul magnified Him.”24 Magnifying lenses provided artists with the visual means to convey this concept of actual and metaphorical magnification in optical terms. The tradition of depicting an apostle using spectacles to “magnify” text was, I suggest, a reference to the Virgin’s supreme act of magnification as expressed in her canticle of joy.

Although the tradition associating optical magnification with the Magnificat is found most consistently in Death of the Virgin images, the concept appears to have had wider currency outside of this particular subject.25 A bas-de-page in a mid-fourteenth-century French breviary (Bodleian Library, MS. Canon. Liturg 192, fol. 199r; fig. 7) offers a particularly sophisticated visual precedent for a polysemic understanding of the idea of magnification in relation to the Magnificat. The image, which appears beneath the opening of the Psalms (as far as Psalm 3:8), shows a hybrid man holding a (comparatively) large disk or lens, on which is written in minute text the Magnificat and part of the Ave Maria. The reference to magnification here is more literal and “enactive” than the examples cited above, as the miniaturized text on the disk only becomes legible with the application of a magnifying lens. (We might also assume that the artist used a magnifying lens to produce the image). Beyond a simple representation of magnification, this image actually combines conceptually the experience of looking at and reading the Magnificat text.

Alternatively, the association in Van Eyck’s painting may not refer specifically to the Magnificat but to the same dual concept of magnification (optical and biblical/devotional) to which the lenses in these images refer. By holding his spectacles over his manuscript, Van der Paele literally “magnifies the Word” (assuming he is reading Scripture). This, of course, recalls the liturgical appellation of Jesus in Saint John’s Gospel as “The Word”; a title referring specifically to John’s only description of Christ’s Incarnation (John 1:14): “Verbum caro factum est” (The Word was made flesh). The fact that the text in the painting is not legible perhaps suggests that we are supposed to understand this detail simply as “words.”

In the context of the incarnational relationship between Christ and his mother, it seems quite plausible that Van Eyck could have included the spectacles not only as a reference to the canon’s visible adoration of the Virgin and Child but also in reference to the Virgin’s supreme act of magnification. Alongside the parrot and the flowers, the viewer is able to draw on a range of symbolic ideas associated with these objects, each emphasizing a Mariological view of the Incarnation within the wider context of Christ’s redemptive death. These symbols do not, however, constitute an iconographic program. Each apparently operates according to basic linguistic associations similar to the one I am proposing for the word “magnify”: nagelbloem (the carnations), Cruciferae (the mustard flowers), Ave (the parrot), schild/schilder (the shield and reflection of the artist), and perhaps even Paele/pala (a single-field Italian altarpiece).

In the wider institutional context of Saint Donatian’s church, it is also significant that the Magnificat was the single most important text in veneration of the Virgin.26 As well as its place in Vespers, the Magnificat was sung every Sunday as well as on special feast days. In more specific reference to Van der Paele himself, we also know that his deceased brother, Judocus–a former chaplain of Saint Donatian’s, mentioned in Joris’s 1441 foundation–had in 1401 endowed a Magnificat antiphon which was used in the most elaborate setting of the text for Saint Donatian’s feast day on October 14.27

Optical Symbolism

The optical character of Eyckian paintings derives from the way in which visual phenomena such as transparency, luminance, shadow, reflection, and refraction are translated, in painterly terms, into what might best be called a descriptive visual language. At its most basic level, this language literally describes these effects visually: Saint George’s helmet and armor, for example, reflect a distorted view of the painted scene and his shield reflects an implied space in front of the painting, including a standing figure (probably the artist; fig. 8); the lit candles of Saint Donatian’s wheel create a profusion of specular highlights, which articulate the fine gold work of his crozier and the flashed gold thread of his brocade garment (fig. 9); the gemstones in Donatian’s morse display adamantine, vitreous, and silky lusters according to how light is reflected differently on their surfaces (fig. 10); and the lens of the canon’s spectacles visibly distorts the text beneath, casting a shadow onto the page (fig. 2). By including a range of specular objects that respond dramatically to effects of light, Van Eyck instilled his painting with a very particular aesthetic–engaging the viewer’s sensitivity to the function of light.

This increased awareness is not, however, simply a matter of observing isolated descriptive details such as those I have described above. In pictorial terms, light from the viewer’s space in front of the painting implicitly makes the objects and figures in the foreground visible. In actual (material) terms, the layering of variably translucent paint over a reflective ground manipulates real light to produce sensations of differing luminance. As well as describing effects of light, therefore, the painting also re-creates them, further preventing the viewer from separating optical metaphor from the optical concerns of the style and technique.

This optical mode of description encourages an equivalent mode of looking, whereby the sensitivity to effects of light, which the painting itself activates, allows for substantial interpretative movement between straightforward perception (inviting comparisons especially between visual experience and the sensation of looking at a painted equivalent) and the detection, or even creation, of meaning. As part of this process, there is also a kind of progression from the overall impression of the painted reality–determined by the way in which light is reflected, refracted, and transmitted in real and pictorial terms throughout the entire scene/surface–to localized descriptions of specific effects, which are more easily related to particular objects such as Saint George’s shield or the canon’s spectacles.

Although viewers are likely to assume that the canon’s spectacles contained magnifying lenses, closer inspection of the distortion produced by the lens does not make this idea explicit. As is typical of Van Eyck’s faithfulness to accurate optical description, he does not show the text visibly larger beneath the lens, but slightly blurred. Although this observation (which would not have been physically accessible to most early viewers of the painting) at first seems to contradict the idea of enacting the effect (and concept) of magnification, this is not the case. Rather than showing a symbolically more obvious, but naturalistically inaccurate distortion of visibly enlarged text, Van Eyck instead describes the distortion typical of a real magnifying lens held in this same position.28

The suggestion that viewers would have been particularly responsive to the painting’s optical language, and the potentially symbolic ideas associated with it, is confirmed by the inscription around the frame, which clearly engages a kind of optical symbolism and integrates symbolic allusion with the concerns of visual description:29

For she is more beautiful than the sun, and above all the orders of stars; being compared with the light, she is found before it. She is the brightness of the everlasting light, the unspotted mirror of the power of God.30

Although taken from Wisdom 7:26, the same text was used in reference to the Virgin in the liturgy for the feast of her assumption and its context here is clearly Marian.31 This optical metaphor, however, also refers, more ambiguously, to the panel–which is itself a kind of spotless mirror–or, more specifically, to the optical mode of description it employs. This connection is reinforced by the association of Saint George’s reflecting shield with the painted panel through the double meaning of the Middle Dutch word schild, and the resulting implication that the panel is a kind of mirror and the painting itself is equivalent to a reflection.32

The optical language of the painting and the allusive mode of looking it promotes also activates existing Marian symbols that would have been familiar to some viewers through prayers and hymns. As Carol Purtle’s study demonstrated, Van Eyck’s Marian paintings show a consistent interest in dealing with the mystery of the Incarnation.33 By far the most fundamental symbolic reference to this event employed in his paintings is the visual metaphor which proposes that the throne room–the standard setting for his Virgin and Child paintings–is a kind of chamber, equivalent of the Virgin’s womb, into which Christ, the Light of the World, passed at his incarnation. Thus, the description of light itself takes on both a metaphysical and mystical significance which engages every surface, including the surface of the painting itself, with the potential for allusive meaning. The suggestion that matter itself is made visible in the painted scene by real and pictorial light–an idea suggested by the language of the painting–in this context extends beyond mere description, becoming a kind of enactment of the incarnational metaphor.

A more specific symbolic reference to the Incarnation derives from an existing optical metaphor in which it was suggested that Christ passed into the womb of the Virgin just as light passes through clear glass without breaking it.34 As Millard Meiss argued, it is likely that Van Eyck and his audience would have been familiar with this idea through numerous popular hymns, poems, and treatises in which it featured.35 We know that one such fifteenth-century hymn, “Dies est Laetitiae,” was apparently known to Van Eyck, as the original inscription around the frame of his Berlin Virgin in a Church (ca. 1426-28) was taken from the second stanza. The fifth stanza of the hymn reads: “As the sunbeam through the glass passeth but not staineth, Thus the Virgin as she was, Virgin still remaineth.”36 Significantly, the topos relied upon the material qualities of glass–primarily its transparency–not upon the form of the object visualized. Consequently, the same visual allusion applies to the light that passes through the windows into otherwise dim spaces and also to objects within these spaces through which this light is reflected and refracted.

Some Eyckian paintings make this idea quite explicit by showing a gilded ray passing through a window pane (the Washington Annunciation, for example; fig. 11) or dappled sunlight streaming through church windows onto the floor inside (the Berlin Virgin in a Church; fig. 12). Others use a glass carafe, prominently placed in sunlight (the Ghent Altarpiece Annunciation and the Lucca Madonna, for example; fig. 13). In further examples, such as the Lucca Madonna, The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, and the Dresden Triptych, the light passing through panes of bull’s-eye glass is more allusive (fig. 14). In each case, however, there is no separation between open references to this concept and less obvious references. Likewise, there is no clear separation between the objects that allude to this symbolic idea and the materials they are made from, the optical effects they produce and the way they are described. In the Lucca Madonna, for example, the glass carafe is suggestive of the light-through-glass incarnation topos and the brass basin is suggestive of the speculum immaculatum epithet. These more obviously symbolic descriptions of glass and metallic objects are accompanied by multiple examples of similar specular descriptions, such as transmitted and reflected light through the bull’s-eye glass panes and gemstones, and reflected light on the lions and the pearls. Consequently, it is very difficult to separate symbols that refer to specular metaphors from straightforward naturalistic descriptions of light. Crucially, far from inviting the viewer to make such distinctions, I would argue that the painting actively works against this kind of response.

The failure to firmly ascribe a single symbolic or nonsymbolic meaning to them is not, I suggest, a failure of methodology or its application but is indicative of how these objects were intended to function. The Van der Paele Madonna is filled with subtle allusive descriptions of light which collectively contribute to the incarnational focus of the painting. As a typical example of the symbolically allusive specular objects that distinguish Van Eyck’s Marian paintings, I suggest that the canon’s spectacles are open to a range of existing symbolic ideas. In the context of the visual references to Christ’s incarnation conceived in terms of the passage of light through glass, it is likely that the canon’s spectacles would have been open to both general and specific symbolic interpretation. On a specific level, they extend the basic light-through-glass metaphor by introducing the idea of the glass (the Virgin’s womb) as a lens that not only allows light to pass through but magnifies as it does so. In the context of other objects, unified compositionally at the center of the painting, the spectacles operate on a similar linguistic level, offering a connection between the optical concept of magnification and the Magnificat–a text in which the Virgin expresses how Christ magnified her and she in turn magnified him. Certainly not all early viewers would have understood these specific symbolic references, but most would undoubtedly have made both conscious and unconscious connections between familiar and popular optical metaphors and similes for the Virgin (not least the one inscribed on the frame) and the profusion of these same ideas described visually in the painting.

In the wider context of the optical language of Van Eyck’s Marian works, however, the spectacles do not simply convey meaning, they engage meaning at a level beneath (or beyond) the obvious. In so doing, they actively deter the viewer from separating symbol from description. This suggestion obviously raises a number of methodological questions. Perhaps most important among these is the idea that obviousness is not an adequate or reliable criterion for the determination of symbolic meaning, as is sometimes asserted. As other scholars have already suggested, in order to fully understand the ideas contained in Van Eyck’s paintings, we need to consider how they communicate these ideas. The preceding discussion suggests that Van Eyck’s mode of communication was more fluid than fixed, involving a remarkably integrated relationship between description and meaning. Our attempt to interpret objects such as Canon van der Paele’s spectacles should likewise allow a certain degree of fluidity determined by what the painting itself allows or dictates.

The idea that symbols are disguised in Van Eyck’s painting by an ostensible naturalism is also problematic: naturalism, as I have suggested, often controls, reveals, and reinforces objects that allude to symbolic ideas. Far from being disguised symbols, Van der Paele’s spectacles are very much concerned with articulating the recognition of symbolic meaning in primarily visual terms.

A second problem, which is sometimes presented against the idea of disguise, is the implication that naturalism was in some sense a vehicle for symbolism. My analysis confirms that this kind of hierarchical progression is untenable. The decision to include the canon’s spectacles in the painting reflects not only symbolic ideas influenced or determined by circumstances of patronage and the intended audience but also Van Eyck’s own interest in describing specular materials in his paintings. His Marian works are filled with specular objects and striking descriptions of light, which encourage the viewer to visualize (established) devotional ideas about the Virgin that use the same optical language. Crucially, however, there is no reason to suppose that these objects were selected according to purely symbolic ends; the symbolic ideas associated with reflective and refractive objects, such as the canon’s spectacles, were also controlled by the visual concerns of Van Eyck’s practice–the very traits that make his paintings “Eyckian.” His evident fascination with translating visual experience into painted equivalents no doubt encouraged him to select objects and settings that allowed the greatest potential for describing its most dramatic effects. What makes his paintings so distinctive in their approach to symbolism is not the way in which symbols are disguised in reality, but the way in which optical concepts are presented symbolically, according to existing Marian symbols, and literally as part of a descriptive language. The overarching concern with the visual potential of optical concepts, and the materials and devices that produce them, is what unifies and integrates these two complementary aspects of his practice; in short, this is what Panofsky might have called the “personal tendencies of the master.”